When a patient presents with an iris problem, deciding on the proper course of management can be challenging, since a lot depends on the cause and extent of the damage. Some cases can be well-served with a reparative surgery, while others may need an implant. Here, experts well-versed in dealing with these cases explain how they approach them.

The Patient’s Plight

Patients with aniridia or damaged irises can suffer from severe light sensitivity and are often unhappy with the appearance of their eyes. Also, a damaged iris admitting too much light can result in reduced vision, halo and glare. Treatment options include sutures and artificial iris implantation.

“When there is no iris or if the iris is damaged, going outside on a bright, very sunny day can be quite an issue,” says Michael Snyder, MD, who is in practice at the Cincinnati Eye Institute. “While it’s an issue for people with a natural crystalline lens, it can become an even bigger issue for people who have an IOL. The natural lens typically fills the entire space at the front of the eye, whereas most IOLs are about 6 mm across and only fill up about half of that diameter. So, these patients not only have excess light entering the eye, but that light is only focused when it’s going through the implant. All of the light that goes around the implant causes tremendous light sensitivity and can also reduce contrast sensitivity.”

Dr. Snyder likens that reduced contrast sensitivity to someone opening the door of a movie theater during a matinee. “The projector is still focused on the screen, and the same number of lumens of light are still hitting the screen,” he says. “But, now there’s defocused light entering the environment, and it reduces the viewing experience. Now, imagine that you have that experience all day long when the focused light going through the lens is diminished by the defocused light going around it. Furthermore, the light that strikes the edge of the lens can cause problems with glare, arcs and halos, as well. Some folks can even have second ‘shadow’ images in the eye. So, it can be a really complex, vexing issue.”

Some people are born aniridic, while others lose iris tissue through trauma or surgical complications. “These can result from either surgical misadventure or removal of iris or ciliary body tumors,” Dr. Snyder explains.

Additionally, diseases, such as iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, can result in a damaged iris. “And, although their irises aren’t damaged, albino patients can experience severe light sensitivity because they have no pigment in their pigment layer,” Dr. Snyder adds. “While the iris is not structurally damaged, it is functionally damaged.”

|

Treatment Options

Dr. Snyder adds that treatment depends on the extent of the damage that’s present. “If a patient has a small defect from the removal of a small tumor, for example, or a small defect from a trauma, it’s often possible to close that defect with sutures and apposing the edges of the iris that are there,” he says. “Some people’s irises are very stretchy, and you can close a pretty large defect. Other people’s irises are not so elastic, and when you put a stitch in, the suture material just cheesewires through and falls out. It’s difficult to predict which irises will be elastic and which irises will not. I’ve been surprised before. Some irises can be stretched much more than you initially think, and others really don’t stretch much at all.”

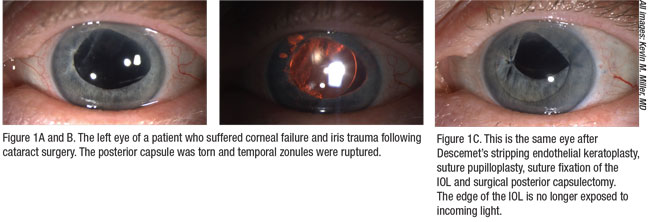

Kevin M. Miller, MD, agrees. “We are fairly limited in the sizes of the defects that we can close with sutures,” he says. “In a patient who has a traumatic mydriasis, the pupil sphincter muscle has been ripped open. Those can often be closed with a purse-string type of pupilloplasty. In patients who have a laceration through the iris or just a small piece of the iris missing, we can often close those with sutures. We can close up to maybe a two-clock-hour sectoral defect, and we can close an iridodialysis, where the iris has been ripped away from its root,” says Dr. Miller, who is in practice at the Stein Eye Institute at UCLA.

Unfortunately, the majority of iris defects are not amenable to suture repair. “For them, they either limp along with tinted contact lenses, by patching the eye, squinting or closing the eye, or they have an artificial iris implanted,” Dr. Miller explains.

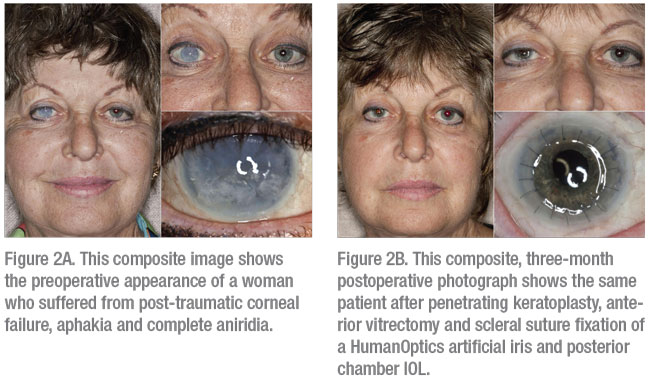

Three different artificial irises are currently being marketed; however, only one, the CustomFlex Artificial Iris by HumanOptics, is currently approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

CustomFlex Artificial Iris

Approved in May 2018, the CustomFlex Artificial Iris is indicated to treat congenital aniridia, as well as iris defects caused by albinism, trauma or surgical removal due to melanoma.1 It is made of thin, foldable silicone and is custom-sized and colored for every patient. To implant CustomFlex, the surgeon makes a small incision, inserts the device, unfolds it and smoothes out the edges. The device is held in place by the anatomical structures of the eye or by sutures, if necessary.

The CustomFlex was found to be safe and effective in a non-randomized clinical trial of 389 patients with aniridia or other iris defects. The study measured patients’ self-reported decrease in severe sensitivity to light and glare after implantation of the device, increase in health-related quality of life and their satisfaction with their cosmetic appearance. More than 70 percent of patients reported significant decreases in light sensitivity and glare as well as an improvement in health-related quality of life. Additionally, 94 percent were satisfied with the appearance of the artificial iris.

Both the device and the surgical procedure had low rates of adverse events. Complications associated with the CustomFlex Artificial Iris included device movement or dislocation, strands of device fiber in the eye, increased intraocular pressure, iritis, synechiae, and the need for secondary surgery to reposition, remove or replace the device. Complications associated with the procedure included increased intraocular pressure, hyphema, cystoid macular edema, corneal swelling, iritis, retinal detachment and secondary surgical intervention.

The device shouldn’t be implanted in patients with uncontrolled or severe uveitis, microphthalmos, untreated retinal detachment, untreated chronic glaucoma, cataract caused by rubella virus, rubeosis, certain kinds of damaged blood vessels in the retina, and intraocular infections. It is also contraindicated for pregnant women.

“It’s a particularly unique device in that it can be placed either passively in the capsular bag for a patient who is having the procedure at the same time as cataract surgery, or it can be sutured to the eye wall in a patient who has no capsular structures and perhaps might require a sutured implant lens, for example,” Dr. Snyder explains. “The device is custom made and matched to a picture taken of an uninjured eye in patients with a traumatic injury in one eye. A congenital aniridic can present a picture of an eye color that he or she likes. The picture gets sent off to Germany, the artificial iris is manufactured based on the picture, and then it’s implanted in the eye. The matches are usually pretty realistic.”

Dr. Miller notes that there is no standard surgery for implanting an artificial iris. “Ninety-five percent of the patients that I see with damaged irises are patients with trauma,” he says. “Because of the nature of trauma, each eye looks different, so there’s no standard surgery. The traumas tend to fall into four general categories: blunt trauma without globe rupture; blunt trauma with globe rupture; penetrating trauma; and surgical trauma. The last cause is actually pretty common.”

He explains that the comorbidities of this group are diverse. Many of these patients have corneal scarring and corneal failure. “So, for those patients, we often perform a corneal transplant at the time of the artificial iris repair,” Dr. Miller says. “Approximately 40 percent of patients will have glaucoma requiring some sort of medical or surgical management at the time that they undergo the iris repair. In terms of lens status, patients must have a cataract, a lens implant, or be aphakic at the time we manage the iris issue. We don’t operate on eyes with clear crystalline lenses.”

The approach to the iris portion of the procedure depends on everything else that is going on in the eye, Dr. Miller says. There are two different ways to place the artificial iris. In simpler cases, it can be injected through a lens-style injector system. In others, it can be placed with forceps, or it can be dropped in through a corneal transplant incision.

“How we fixate the iris also varies from eye to eye,” he says. “If there’s an intact capsule, it’s sometimes possible to trephinate the iris and stick it inside the capsule. That’s one way of passively placing the iris inside the eye. In some cases, we will place the iris passively in the ciliary sulcus if there’s adequate capsule and zonular support to hold it there. And then, the other way to fixate the iris is to suture it to something, and there are many different suture techniques. We can suture the iris to the sclera; we can suture the iris to a lens implant, which is then sutured to the sclera; and we can suture the iris to residual iris tissue. The most common scenario is where we have to implant an iris and a lens at the same time. These eyes usually have no capsule and no zonular support, so we’ll suture the lens implant to the back of the artificial iris and suture the artificial iris to the sclera. That’s actually very common.”

|

The Future

According to Dr. Miller, artificial irises provide a great cosmetic result. “In a patient who didn’t have other obvious trauma, you probably wouldn’t be able to tell that he or she had an artificial iris if you met him or her in a social situation,” he says. “So, cosmetically, they’re really good. However, many of us would love to see an integrated optic. The artificial iris is just a wafer-thin piece of silicone that rolls up, and it’s got a fixed 3.35-mm pupil. It would be nice if we could pop a 22-D optic, or whatever power is necessary, inside the pupil and have it clip to the iris. Then, we wouldn’t have to separately suture a lens implant to the back of the iris. So, that’s a hope for a future development.”

However, he notes that artificial iris implantation isn’t common, so funds for clinical trials are scarce. “Those of us who brought the artificial iris to the market in the U.S. did it for free,” Dr. Miller says. “Developing products and making improvements requires funds, and this company could never possibly fund a clinical trial. In the clinical trial we ran, the patients had to pay for the device, and it wasn’t cheap. The surgeons performed the iris portion of the surgery for free. We would bill out whatever covered service we could. So, future developments will depend on another group of investigators willing to do the same.” REVIEW

Dr. Snyder has a financial interest in HumanOptics and VEO Ophthalmics, and Dr. Miller has no relevant financial interests to disclose.

1. Artificial Iris approval notice. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-artificial-iris.