In the worl of intraocular lenses, a perfect implantation may only be the beginning of the story. Patients may become unhappy; problems such as posterior capsule opacification may cloud vision; zonular problems may leave the capsule dangling or adrift. The list of potential postoperative issues is long—and sometimes, a well-intentioned attempt to solve a problem may make matters worse.

Here, four experienced surgeons share their approaches to dealing with three errant IOL scenarios that any ophthalmic surgeon might encounter.

Case 1: An unhappy multifocal IOL patient wants his IOL removed because of poor-quality night vision. The posterior capsule has had a YAG capsulotomy.

All of the surgeons interviewed agree that the presence of the posterior capsulotomy makes explanting this lens challenging. For that reason, they recommend exhausting all alternative options before attempting the explantation. They also recommend having the patient sign a comprehensive informed consent if he's determined to proceed.

"The patient has to be apprised of the fact that, while we want to alleviate or reduce the unwanted poor-quality night vision, removing a lens in the presence of an open capsule bears a higher risk of complications such as CME, retinal tears and vitreous loss," says Kenneth J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, surgeon director of Rosenthal Eye and Facial Plastic Surgery in Great Neck, N.Y., associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Utah Medical School, and assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU Medical School. "Furthermore, there have been cases in which exchanging the lens did not improve the quality of the patient's night vision, so there's a risk that the exchange won't do anything. In a case like this, unless the vision is substantially impaired and the patient is really incapacitated, I'd wait as long as possible to give neuroadaptation a chance to take place before deciding to exchange the lens—up to a year, if possible."

"In this situation, I'd try using medical management to make the patient happy with the existing lens before doing an exchange," says Richard S. Hoffman, MD, clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, who practices at Drs. Fine, Hoffman & Packer in Eugene, Ore. "For instance, with a ReZoom lens, you may be able to improve the quality of night vision by putting the patient on pilocarpine or Alphagan to prevent the pupil from dilating as much at night.

You could put the patient in polarized lenses, or give him -1 D driving glasses if he's

Managing the Capsulotomy

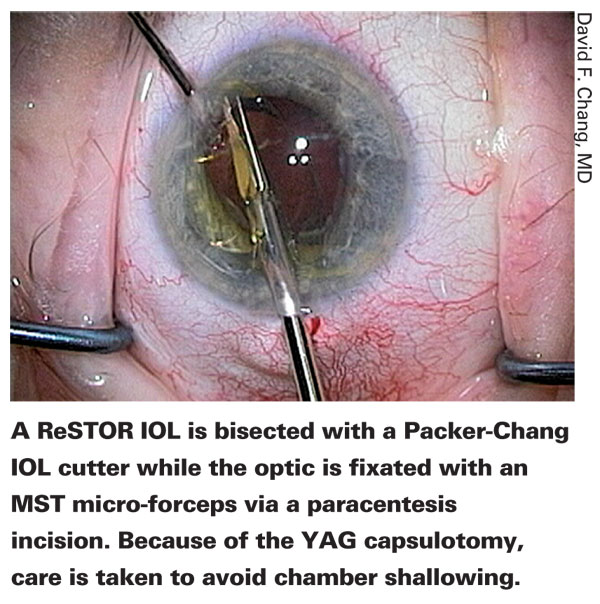

"In this case, it's reasonable to assume that removing the IOL will result in extension of the YAG capsulotomy out to the periphery," says David F. Chang, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the

Dr. Chang favors using a dispersive ophthalmic viscosurgical device such such as Viscoat to re-open the capsular bag and separate capsular attachments to the IOL.

"Viscoat is also optimal for tamponading a capsular defect because it resists aspiration better than any other OVD," he notes. "Because of the open posterior capsule, Viscoat should be repeatedly instilled over the defect to avoid rupturing the hyaloid face with chamber shallowing.

"With a single-piece IOL such as ReSTOR, I would try to displace the optic laterally once it's elevated out of the bag," he continues. "If the anterior chamber is large and deep enough, it may be possible to first implant the replacement IOL to cover and shield the posterior capsular opening before removing the multifocal. Alternatively, the multifocal IOL should be bisected and removed first."

Dr. Chang prefers to use MST bimanual lens removal instrumentation (MicroSurgical Technology,

"The latter is able to cut even the stiff hydrophobic acrylic material of the Tecnis multifocal, and the straight shaft won't gape the incision to the point of shallowing the anterior chamber."

Michael E. Snyder, MD, who practices at the Cincinnati Eye Institute in

"Even though the YAG opening may be small, it will enlarge when the capsular bag is opened to remove the implant," he says.

"Assuming that the patient is al-ready aware of the risks and is still willing to undergo a surgical intervention, there are several things I would do," he continues. "First, I'd give the patient an intravenous injection of Mannitol, 30 minutes prior to surgery, to shrink the vitreous volume. This reduces vitreous pressure; the vitreous will follow gravity and sink more posteriorly, so I'm less likely to disturb it during the surgery. In the OR, I'd either create a temporal wound or reopen the old wound, depending on how long ago the original surgery took place. In this situation I'd use the back edge of a 25-ga. needle to lift the capsule off of the anterior surface of the IOL. Next, I'd inject DisCoVisc into the anterior chamber and then under the capsular margin. The DisCoVisc would dissect the anterior and posterior capsule leaflet apart and reopen the bag. I'd add DisCoVisc liberally underneath the implant lens to create a barrier for the vitreous gel.

"Once the bag was open in all areas, I'd bring the optic into the anterior chamber and then dial the haptics into the anterior chamber, too," he says. "I'd bisect the lens with IOL-cutting scissors, remove the lens through a 2.75-mm opening and inject a three-piece lens into the sulcus. If the capsulorhexis is smaller than the new lens optic, I'd capture the optic through the anterior capsulorhexis, with the haptics remaining in the sulcus. If the anterior capsulorhexis is larger than the planned new optic, I'd place the lens in the sulcus, making sure to select an IOL with a rounded edge to prevent the possibility of pigment dispersion.

"Finally, I'd remove the viscoelastic as in a regular cataract case and inject carbachol," he notes. "The carbachol will provide intraocular pressure control for a few days, since some viscoelastic will definitely be left behind the optic. Of course, if I encountered vitreous at any time during the procedure, I'd remove the offending gel from the anterior segment using a pars plana approach to anterior vitrectomy."

Dr. Hoffman says it's tricky to viscodissect the bag open without extending the opening in the posterior capsule out to the equator. "The lens material makes a difference," he notes. "An acrylic lens will be much more challenging than a silicone lens because the bag is usually adherent to the IOL. But you should be able to free up the optic from the capsular bag by injecting the viscoelastic in multiple quadrants.

"The challenging part is getting the bag completely open where the haptics are," he continues. "There's a very good chance that the haptics are going to be trapped within the capsular bag—but you might be able to free up the optic. If you can do that, you can go in with microincision scissors and amputate the haptics from the optic. Then you can bring the optic up into the anterior chamber, cut it in half and remove each half, implant a monofocal lens in the sulcus, and leave the haptics in the capsular bag. The patient might have issues with retained viscoelastic and elevated pressure for a day or two, so you'd want to treat him pretty aggressively postop with Diamox and a topical beta blocker and an alpha-agonist such as Alphagan."

Dr. Hoffman notes that in this situation you might have to take the entire lens and the capsular bag out of the eye and put in an anterior chamber lens. "This patient's not going to be happy with an anterior chamber lens, however," he points out. "So in the informed consent, you need to make the patient aware you might not be able to leave the capsular bag intact, in which case you're probably going to end up with a vitrectomy and a higher rate of retinal detachment; and you may have to sew in a lens, which has a higher potential for vitreous hemorrhage and CME, or sew a lens to the iris. I'd personally prefer not to use this option, because the potential for ending up worse off is not worth removing it."

Dr. Rosenthal says he'd free the adhesions between the anterior capsular rim and the IOL, lift up the edge of the lens using a Sinskey hook and inject a retentive viscoelastic such as Healon5 to elevate the IOL and tamponade the open posterior capsule. "Then I'd carefully either cut the lens or refold it using a cyclodialysis spatula and cross-action IOL insertion forceps, and explant it," he says. "In some cases it may be difficult to unfuse the anterior and posterior capsule in the area of the haptics, so I'd have to amputate the haptics and leave them behind. Note that you can make as many paracenteses as you need to manage these maneuvers comfortably; most paracenteses are astigmatically neutral and self-sealing.

"When I implant the new lens, I put the lens in the sulcus and then capture the optic within the anterior capsular rim, which at this point is usually still intact," he continues. (See image, above.) "This is possible even if I've had to amputate the haptics of the old lens and leave them in the capsule. In any case, placing the new lens completely inside the capsule would run the risk of extending the posterior capsule opening and destabilizing the lens implantation. In rare cases I might put the lens in the ciliary sulcus.

"If I were suspicious of vitreous in the anterior chamber, I'd inject triamcinolone to locate it," he adds. "I might consider doing a 25-ga. self-sealing vitrectomy through the pars plana, which would also provide a means to remove any Healon5 sequestered behind the lens, minimizing the chance of a postop pressure elevation."

An Ounce of Prevention

All of these surgeons agree that the best solution to a problem like this is to avoid creating this situation in the first place. "If you have a patient who is unhappy with her multifocal IOL and has opacification, many surgeons think, 'I'm going to fix the problem by doing a YAG capsulotomy.' But if it's a new patient, you don't know if he's unhappy because of the opacification or because of the multifocal optics," Dr. Hoffman points out.

"Once you open up the posterior capsule with a YAG capsulotomy, doing a lens ex-change is much more difficult and risky. The patient may have spent a lot of money for a multifocal lens; the last thing you want is to cause a retinal detachment just because he's unhappy with haloes and glare. You need to make sure the patient is aware that you could be taking him from 85 percent of where he wants to be to 10 percent of where he wants to be.

"I tell any unhappy multifocal patient who has opacification that if I do the YAG capsulotomy he's stuck with the lens, even if he still has problems," Dr. Hoffman adds.

"Then I ask, 'Were you unhappy with your night vision from the first day after surgery?

Was there ever a point at which you were happy with this lens?' If the patient was never happy with the multifocal lens, then it's probably better to remove the multifocal lens before you do a capsulotomy. If the patient says, 'No, it was great for a month, then I started having problems with glare and night vision,' you can probably blame it on the posterior capsule being opacified. But even in that situation, you need to warn the patient that the YAG capsulotomy might not solve the problem—and if it doesn't, he'll be stuck with the lens."

Dr. Snyder offers another alternative surgical approach when it's not clear whether multifocal optics or PCO is the problem. "One of the things I've done in a few of these cases, if I'm not sure which factor is causing the complaint, is open up the capsular bag in the OR and perform a primary posterior capsulorhexis, leaving the implant lens in place," he explains. "If the problem was the posterior opacity, it will be resolved in the weeks after the surgery. If it isn't resolved, the problem is likely to be the multifocal optics.

"The reason this is preferable to performing a YAG capsulotomy is that a posterior capsulorhexis will allow me to open the capsular bag later for an IOL exchange without splaying the posterior capsule open," he continues. "After a YAG capsulotomy, the edges of the opening are sharp points; as soon as you use viscoelastic material to separate the anterior and posterior capsule to get the implant lens out, the back membrane will split further open. In contrast, a posterior capsulorhexis creates a continuous circular opening with more structural integrity, so if I peel apart the anterior and posterior capsules using viscodissection the posterior capsule will remain intact.

That makes lens exchange far easier, and I can still put the implant lens in the capsule, or even use the posterior capsule to fixate the new lens by optic capture. Yes, a posterior capsulorhexis involves somewhat more risk than a YAG capsulotomy; but if an exchange becomes necessary, a posterior capsulorhexis will make the exchange surgery less risky and less challenging."

Case 2: A pseudophakic patient has delayed dislocation of the entire bag containing a three-piece IOL, eight years postop. At the slit lamp, the IOL complex is floating in the mid-anterior vitreous.

"I see more and more cases like this," says Dr. Hoffman. "These are patients with pseudoexfoliation who had uncomplicated cataract surgery, but seven to 10 years later their zonules are degrading because of the pseudoexfoliative process. They've got marked zonular weakness, and the bags subluxate."

In this situation, Dr. Chang favors removing the complex. "These IOL-bag complexes can be tricky to remove for multiple reasons," he notes. "The haptics are encased and not easily accessible. The complex, which often incorporates a Soemmering's ring, has a large diameter. If the complex is sitting in the anterior to mid-vitreous, I'd use the Viscoat posterior assisted levitation technique to help support and then levitate the complex into the pupillary plane using the OVD cannula inserted through a pars plana sclerotomy, as I've previously described."1

Dr. Chang explains how the PAL technique works. "The pars plana sclerotomy is made 3.5 mm posterior to the limbus in an oblique quadrant, and the OVD cannula tip is kept in the pupillary plane where it can be visualized," he says. "As a safety net, dispersive OVD is first injected behind the IOL to buoy it. Small additional injections of OVD can be used to maneuver the IOL complex into the best position for levitation.

"The surgeon must be careful to avoid injecting an excessive amount of OVD," he notes. "Doing so could force vitreous out through the pars plana incision. I prefer to use Viscoat because it resists aspiration, and whatever amount can't be removed is less likely to cause a protracted IOP spike.

"The cannula tip then mechanically props the IOL into the anterior chamber or pupillary plane, where it can be grasped with forceps through a limbal incision," he continues. "After removing the IOL, an anterior vitrectomy is performed with a self-retaining infusion cannula through a corneal paracentesis site. I use the pars plana sclerotomy site for the vitrectomy handpiece to avoid incisional leak, and later close it with an interrupted suture. Typically, I would implant an anterior chamber IOL."

Exchange or Reposition?

"I'd address this case in combination with a vitreoretinal surgeon," says Dr. Snyder. "If there's a significant Soemmering's ring with a lot of cortical material in the peripheral bag, my preference would be to have the vitreoretinal surgeon remove any vitreous gel encased around the complex and bring the complex forward using intraocular forceps; then I'd remove the entire complex and exchange it for a sutured PMMA PC IOL.

"If, on the other hand, there's minimal cortical material inside the capsular bag, I wouldn't exchange it," he continues. "Once the vitreoretinal surgeon has brought it forward, I'd place an 8-0 Gore-Tex suture through the capsular bag, underneath the apex of each haptic, and place both ends of the suture through the ciliary sulcus. I'd tie the knot externally, and then rotate it inside the eye wall and cover the exposed suture track with conjunctiva."

Dr. Snyder offers additional suggestions. "I make my suture passes at each apex about 3 mm apart," he says. "That does two things: First, a little distance between the two suture passes makes it easier to bury the knot; second, I can move the implant back and forth a little bit inside the eye on that 3-mm track, to fine-tune centration. I wouldn't attempt to suture the complex to the iris, however; having the capsulorhexis wrapped around the lens can make that very difficult to do.

"Also, many surgeons, as soon as they take down conjunctiva, apply cautery in that area so there's no oozing on the surface," he notes. "I don't cauterize in the area where I'm passing Gore-Tex sutures. Instead, I take down the conjunctiva early at the site of suturing and let the bleeding stop on its own—a helpful strategy I learned from Dr. Lisa Brothers Arbisser. This reduces the chances of suture exposure or melting, since the sclera has not been devitalized."

Dr. Hoffman avoids removing the entire complex and putting in an anterior chamber lens. "That's much more invasive," he points out. "There's a greater chance of vitreous loss and retinal detachment. And, you have to do it through a large incision. If the bag isn't floating too far behind the iris, if it's in a place where you can get sutures to the haptics, you can accomplish the whole fixation process through two little paracenteses and two small scleral pockets." Dr. Hoffman adds that he's created a variation on the technique of looping sutures around the haptics of the IOL and sclerally fixating them. "I create scleral pockets and perform the scleral fixation through them, so I don't have to dissect the conjunctiva," he explains.

Dr. Rosenthal suggests a technique that he recently developed for suturing a lens-capsule complex to the iris. "This technique involves coming from behind with the needle rather than from the front," he explains. "It can be difficult to get the needle through a capsule if there's a lot of capsular fibrosis; when you push on the lens, it moves. But instead of fixating the lens with a second instrument, I push the needle in from behind the complex. The lens is pushed up against the iris, and the iris acts as a vise grip to hold the lens while you suture it. I use a double-armed prolene suture, and either place the suture across the IOL surface, through the edge of the anterior capsule and then up through the iris, bringing the ends out through a paracentesis and then tying them; or I bring the suture from behind, ab externo, via the ciliary sulcus and capture the bag haptic complex, and then bring the suture back out through the sclera for fixation or affix it to the iris."

He notes that if he chose to replace the lens instead, the new lens could be an anterior chamber lens, but that wouldn't be his first choice. "I'd favor either suturing a posterior lens to the peripheral iris or suturing a posterior chamber lens to the anterior surface of the iris—a technique I developed," he says.

Dr. Rosenthal notes that in theory the surgeons could bring the lens up into the anterior chamber, dissect the capsule off and then remove the pieces, or simply cut the complex into pieces. "The problem is that in some cases the capsulorhexis may not have been thoroughly evacuated, leaving residual cortical material behind," he says. "That residual material may have caused the capsular contraction and zonular disinsertion. You don't want it to escape from the capsular bag. That's why I would opt for folding the lens and capsule rather than cutting them. Your incision has to be a little larger to remove the uncut, folded complex—but not a lot larger."

Dr. Rosenthal says there are a few other considerations that would affect his decision about whether to keep or remove the old lens. "If the dislocated lens is a foldable lens, it may be best to remove it, because you can remove it without creating a large incision," he notes. "If it's an old, one-piece PMMA lens, you'd have to make a 7-mm incision to get the lens and its bag out of the eye. That's an argument for reattaching it. At the same time, current prolate lenses have much better optics; that's an argument for replacing an older lens, even if a larger incision was required."

Could Capsular Tension Rings Help?

"Scleral fixation is a lot easier to do if those patients have a capsular tension ring inside the bag for 360 degrees," Dr. Hoffman points out. "I now put capsular tension rings in all of my pseudoexfoliation patients—not because they have zonular weakness at the time of surgery, but because I'm worried that they'll develop this problem 10 years later. In some situations, once the complex has subluxated, fixating the ring is much easier than fixating the haptics—for example, if the bag is decentered inferiorly and the haptics are oriented horizontally.

"This kind of scenario presents one of the strongest arguments for using capsular tension rings in patients with pseudoexfoliation, even if the eye doesn't have obvious phacodonesis or zonular instability at the time of cataract surgery," Dr. Rosenthal notes.

"Currently, there's no guarantee that capsular tension rings will actually prevent late dislocation—that study hasn't been done because no CTR has been used widely enough and for long enough to make that assessment. But my experience has led me to believe that placement of a CTR may delay or prevent some of the capsule contraction that helps to cause zonular instability."

Dr. Rosenthal adds, however, that having a capsular tension ring inside the capsule may not totally prevent capsular contraction and zonular instability. "No current capsular tension ring is strong enough to withstand progressive lens epithelial metaplasia," he says. "So in some cases you'll see late dislocation, even with a capsular tension ring."

If the Lens Is Farther Back

Of course, when the zonular attachments are lost, the lens-capsule complex may be farther back in the eye than the anterior vitreous. "When you're examining this patient preop, you need to lay the patient back and see how far back the capsular bag complex subluxes posteriorly," says Dr. Hoffman. "If it goes way back in the eye, it will be hard to reach the lens with sutures and needles. In that situation, you might want to coordinate the procedure with your vitreoretinal surgeon; he could put something like perfluorocarbon in behind the complex to float it back up to a safer place for you to fixate it to the sulcus."

Dr. Rosenthal agrees. "In this situation, part of the preop evaluation should be done with the patient in the supine position," he says. "Using an operating room scope or a portable slit lamp, look at the position of the lens. If the lens complex completely disappears from view—in other words, moves to the periphery—or falls posteriorly, you'll either have to do a vitrectomy to get the lens out, or you'll have to put in a new lens without taking out the old one.

"There's plenty of literature that supports the idea that it's safer to leave a lens in under these conditions than to assume the risk of a total vitrectomy in order to get it out," he notes. "I've left a number of these lenses in the vitreous cavity myself, and the patients have done very well. It's actually more of a problem if the complex is only partly dislocated; then it will keep bobbing up right behind the functioning lens. If it's completely dislocated, often just leaving it the vitreous and putting in a new lens is the way to go. It's important to remember that you don't have to remove every errant lens."

Case 3: A patient has a single-piece acrylic IOL in the sulcus with pigment dispersion and elevated IOP. The posterior capsule is torn. There's a radial tear in the capsulorhexis which is otherwise intact.

"In this situation, the previous surgeon had a problem because the posterior capsule was torn, so he decided to put a single-piece acrylic lens in the sulcus," notes Dr. Hoffman.

"The major point here is that single-piece acrylic lenses are not designed to be put in the sulcus, though many surgeons still do. There's a very high incidence of them causing pigment dispersion syndrome."

"This is a preventable problem," agrees Dr. Snyder. "Single-piece acrylic IOLs should never be placed in the sulcus—period."

Dr. Chang notes that in 2009 the cataract clinical committee of the American Society for Cataract and Refractive Surgery published a paper reviewing combined experience with 30 cases in which single-piece acrylic IOLs implanted in the sulcus caused chronic ocular complications.2 "These IOLs are poorly suited for the sulcus for many reasons and should be explanted," he says.

Dr. Rosenthal adds that many surgeons haven't gotten the message. "A casual survey at the 2009 ASCRS meeting indicated that 40 percent of the surgeons present would still put a single-piece lens in the sulcus," he recalls. "The fact that this is a bad idea is a message that needs to be spread."

Given this patient's situation, Dr. Rosenthal says the priority is to remove the offending lens. "If there are any adhesions, I'd dissect the lens free," he says. "I'd bring the lens up into the anterior chamber under viscoelastic and either cut it or fold it and remove it from the eye. Since the posterior capsulorhexis is torn, I'd tamponade the opening with either VisCoat or Healon5 before elevating the lens. Assuming this is not too long after the original surgery, you now have a marginally stable posterior capsule. You might encounter vitreous, so you should be prepared to do a 25-ga. vitrectomy through the pars plana, using Kenalog to make sure you don't miss any of it.

"Some surgeons might consider moving the single-piece IOL into the capsule," he notes. "If the capsule were intact, that would be reasonable. But in a case like this, you'd run the risk of extending the posterior capsular opening. So, I would probably explant the lens and then implant a three-piece lens, probably acrylic, either in the sulcus or using the optic capture method. The advantage of the latter option is that it not only places the lens in the plane of the capsular bag, thus producing a more reliable refractive result, it also stabilizes the lens and keeps it centered.

"A lens that's placed in the sulcus has a relatively high risk of becoming decentered postoperatively," he continues. "If I couldn't be sure that there was good fixation with the lens optic captured in the anterior capsulorhexis, or if I were to leave the IOL in the sulcus, I would also place at least one, if not two, McCannel sutures incorporating the iris and the haptics. If I were only going to use one suture, I'd probably suture the haptic superiorly. The other option would be to use a lens implant with an oversized optic, so that if it decentered it wouldn't cause edge glare or other decentration problems."

Dr. Chang agrees. "Absent the option of optic capture, our ASCRS committee advocated using a longer three-piece foldable IOL in the sulcus, with rounded anterior optic edges to avoid posterior iris chafing," he says. "Currently, the Staar AQ2010V is the only 13.5-mm long foldable IOL; it does have a rounded anterior optic edge."

Dr. Snyder says the nature of the radial tear in the capsulorhexis would determine how he'd proceed with the replacement IOL. "If the radial tear wasn't inferior, I'd inject a three-piece PC IOL with a round-edge optic into the sulcus," he says. "If the radial tear was inferior, I'd suture the haptics to the peripheral iris, be-cause in an inferior tear the haptic will ultimately find the tear and the IOL will subluxate." He also offers one other possible approach. "If the posterior capsule tear was small and central," he says, "I'd convert it into a posterior capsulorhexis and capture the optic of the new three-piece IOL through it. In that case, no other suture fixation would be required and long-term centration and stability would be guaranteed."

Dr. Snyder is an investigator for Alcon and consultant for Haag Streit and HumanOptics. Drs. Hoffman and Chang have no financial interest in any product mentioned. Dr. Rosenthal receives travel and honoraria from Ophtec and AMO. The author would like to thank Dr. Chang for his help selecting the cases discussed in this article.

1. Chang, DF: "Viscoelastic Levitation of Posteriorly Dislocated IOLs from the Anterior Vitreous." J Cataract Refract Surg 2002; 28:1515-1519.

2. Chang DF, Masket S, Miller K, et al. ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee. ASCRS White Paper: Complications of Sulcus Placement of Single Piece Acrylic IOLs. Recommendations for backup IOL implantation following posterior capsule rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009; 35:1445-1458.

3. Hoffman RS, Fine IH, Packer M. Scleral fixation without conjunctival dissection. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:11:1907-12.