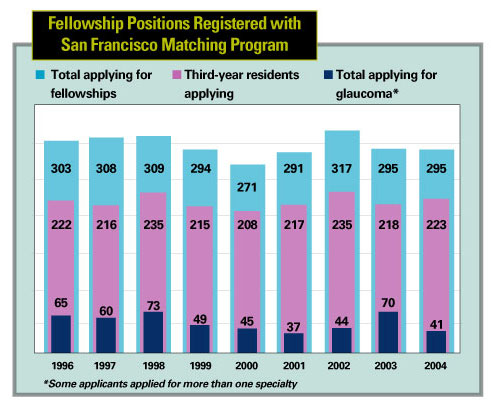

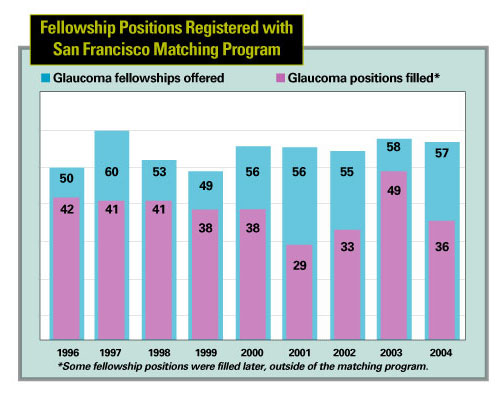

DURING THE PAST FEW YEARS, OPHTHALmologists specializing in glaucoma have noticed a disturbing trend: Despite a healthy supply of ophthalmology residents opting to pursue subspecialty training, the number of residents applying for glaucoma fellowships appears to be declining. (See charts, below and on facing page.) With the "baby boom" generation aging, a dramatic increase in individuals needing glaucoma treatment seems inevitable. (One estimate predicts a 50-percent increase in open-angle glaucoma by the year 2020, with a greater increase in some segments of society.1) Should the number of glaucoma subspecialists decline, a shortage of needed care could result, leading to unpredictable consequences.

We asked several of the nation's top glaucoma specialists to comment on the current situation, its potential ramifications, and what might be done today to ensure an adequate supply of well-trained glaucoma specialists in the years to come.

A Shortage of Care?

Steven J. Gedde, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology and residency program director at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, and Donald L. Budenz, MD, MPH, associate professor in the departments of ophthalmology, epidemiology and public health at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, and associate medical director at Bascom Palmer, believe glaucoma subspecialists will be needed more than ever in coming years, and not just because of the baby boomers aging. "There's a trend toward the comprehensive ophthalmologist focusing more on cataract and refractive surgery and less on subspecialist-type surgery," observes Dr. Budenz. "This will increase the need for skilled subspecialists."

George L. Spaeth, MD, the Louis Esposito Research Professor and director of the William and Anna Goldberg Glaucoma Service at Wills Eye Hospital and Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, believes a shortage of care already exists. "Today, 50 percent of the people in the United States who have glaucoma don't get diagnosed," he says. "Studies of cities in Japan and Poland have found that 70 or 80 percent of the people who have glaucoma in some cities don't even realize they have it. So we're already facing a shortage of care."

Why Not Glaucoma?

Asked why they think residents are opting to pursue other subspecialties, our glaucoma experts suggested a number of possibilities, including poor communication about the advantages of the subspecialty. Peter Netland, MD, PhD, Siegal Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, sees glaucoma as a fundamentally interesting field. "We have research opportunities, patient care is improving, and the need for our services is great," he says. "Young people coming into the field have the opportunity to improve our understanding of the disease and treatment capabilities. But I'm not sure a sense of excitement and opportunity is being effectively conveyed to them."

Economic concerns may also be a factor. "There's a lot of money to be made in retinal surgery, refractive surgery and high-volume cataract surgery," notes Dr. Budenz. "Glaucoma is perceived as too much work for the amount of reimbursement."

Dr. Spaeth agrees. "People want to be able to pay the bills and send their kids to good schools, which have gotten incredibly expensive," he says. "So it doesn't surprise me that fewer people are going into glaucoma."

Dr. Budenz, however, believes this will change as the demand for treatment increases. "If there are too few qualified people to do glaucoma surgery 20 years from now, subspecialists will be able to charge more," he says. "They'll be able to go to the government and say, 'If you want people to do this, you'll have to pay more.' "

The long-term nature of the disease could also be a factor in the dwindling numbers. "It's a disease patients will have for the rest of their lives," says Dr. Spaeth. "You have to build relationships with your patients. In fact, what they do is more important than what we do. If they don't use their drops, they could lose their sight."

Dr. Netland agrees. "It's tough when you're confronted with a disease that you're not really curing," he admits. "But things are improving. Treatments are getting better, so outcomes will keep improving, making it a more positive emotional experience for physicians."

Dr. Gedde is less convinced that having to treat a chronic disease explains the drop in applications for fellowships. "Glaucoma has always been a long-term disease," he points out. "That's probably not the explanation for the downward trend we've seen in the past decade.

"Dramatic advances in treatment options and surgery, such as those recently seen for macular degeneration and in the area of refractive surgery, make a subspecialty seem more exciting and cutting-edge," he notes. "Both retina and cornea seem to be getting a larger number of applicants, and that may be why. A major treatment breakthrough in glaucoma treatment or prevention could change people's perception about this and attract more residents to the field." Dr. Gedde also notes that advances in medical therapy for glaucoma have shifted treatment a little bit away from surgery, which could make the field less interesting to some residents.

Dr. Netland doesn't see any of these issues as insurmountable problems. "They're not unique to glaucoma," he points out. "Besides, there are plenty of individuals who are willing to tackle these challenges."

Dr. Spaeth also notes that although the number of applicants for glaucoma subspecialty training may be declining, the quality of applicants is going up. "We're currently interviewing a record number of candidates for our fellowship positions," he says, "because the applicants have been so strong. These circumstances select out a wonderful group of people. They really want to help their patients."

Will There Really Be a Shortage?

Dr. Gedde notes that a shrinking number of specialists wouldn't necessarily produce a public-health crisis. "I don't think there's any question that we'll have more glaucoma patients in the future," he says. "The question is, will we need more glaucoma specialists? That will depend on the role glaucoma specialists will play and what the scope of general ophthalmology will be. I don't think every patient with glaucoma needs to have a subspecialty-trained ophthalmologist to care for him."

Dr. Spaeth says he's less concerned about a decreasing number of glaucoma subspecialists than he is about decreasing availability of care from any source. "The number of people who are well-trained to take care of glaucoma patients is small right now, and may get smaller," he notes. "Both we and the next generation of specialists need to be asking the right questions, such as: How can we improve the distribution of care?"

Dr. Spaeth also believes that preventing a shortage of care has a lot to do with allocation of limited resources. "If our government spends hundreds of billions of dollars on wars, there won't be much left to care for people who are losing their sight," he observes. "And should we be spending so much money researching keratorefractive surgery, or spend more to find new ways to diagnose and treat diseases that lead to blindness?"

Will Optometrists Fill the Void?

"How a shortage is resolved will depend partly on what the role of optometrists becomes," says Dr. Gedde. "Will they be primary-care providers, or will that be the province of ophthalmology?"

"I think the best way we can avoid having optometrists take over glaucoma care is to attract good people into the field," says Dr. Netland. "If we don't, it will create a vacuum, and that void will be filled by somebody." Dr. Netland observes that whether or not the void would be filled by optometrists depends partly on legal and social issues. "What will optometrists be allowed to do?" he asks. "Who will have access to care? How will government and insurance companies handle the situation?"

On the issue of optometrists helping to diagnose and monitor glaucoma patients, Dr. Spaeth is philosophical. "If we end up with a shortage of glaucoma care and an optometrist is trained to look at an optic disk and decide whether a patient is getting worse, fine. Studies have shown that many optometrists are good at judging the condition of an optic disc, and some ophthalmologists are not so good at it. The most important thing is whether a person is knowledgeable, competent and well-trained."

Dr. Budenz doesn't think a shortage of this magnitude will actually arise. "If there were a shortage of ophthalmologists, you could justify recruiting optometrists and training them to provide medical care in this one instance," he says. "But in the United States we have an overabundance of ophthalmologists, more than enough to take care of the problem.

"Of course, optometrists have already involved themselves by expanding their scope of practice and competing with general ophthalmologists to provide glaucoma medical care," he adds. "However, I've heard from my friends in the pharmaceutical industry that the number of optometrists prescribing a high number of glaucoma medications is in the single digits, percentage wise. Many MDs have a perception that ODs who can prescribe glaucoma drugs are stealing our business, but the reality is that probably very few have jumped into that arena."

|

George L. Spaeth, MD, Louis Esposito Research Professor and director of the William and Anna Goldberg Glaucoma Service at Wills Eye Hospital and Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, is concerned that the public-health aspects of a future shortage of glaucoma care could force politicians to intervene. "I have a hunch that that's what's going to happen if glaucoma care declines while patient numbers increase," he says. "We need to question how we're spending our resources and what we're trying to accomplish." Steven J. Gedde, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology and residency program director at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, notes that the government has intervened in medicine before. "About a decade ago there was a perception in general medicine that we were training too many specialists," he explains. "The government didn't say, 'You have to go into this area,' but they did intervene with scholarships and financial support to medical schools to encourage students to go into primary care." |

What Should We Do Right Now?

Obviously, encouraging residents to apply for glaucoma fellowships could benefit the field in multiple ways. Our experts offer the following suggestions for making the option more appealing:

• Make programs more attractive to candidates. "Programs need to be educationally innovative," says Dr. Netland. "Trainees' needs are changing. We have to provide them with the kind of educational opportunities they seek. Many of their current interests, such as mentoring, were not high priorities 15 years ago.

"We also have to remain technologically savvy and up-to-date," he continues. "For example, here at the University of Tennessee we have a brand new state-of-the-art teaching facility that incorporates tools such as embedded electronics that let trainees practice surgery. These are also tied into our telemedicine capabilities."

• Provide better role models. Drs. Gedde, Budenz and their colleagues at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami surveyed graduating ophthalmology residents in 2003 to find out why they chose either general ophthalmology or subspecialty training.2 Almost two-thirds of the respondents chose to pursue subspecialties. "Factors that influenced their choice of subspecialty included challenging diagnostic problems, role models and mentors, and number of rotations in training," notes Dr. Gedde.

"One area that would be logical to try to develop further is mentoring and role models," Dr. Gedde continues. "Having good role models who are actively involved in your education stimulates interest in the field. If more glaucoma specialists made the effort to get involved as role models and mentors, it could do a lot to incite enthusiasm for this subspecialty."

• Give residents more experience. "The residents we surveyed said that rotations were an important factor when deciding what to pursue," notes Dr. Gedde. "Maybe we should have more rotations, or longer rotations, to increase exposure."

Dr. Budenz agrees. "Most residents do fewer than 10 trabeculectomies during their residency program, compared to 50 to 100 cataract surgeries. I think it takes seeing and doing a lot of cases with postop care to really feel comfortable with it."

• Address residents' concerns about income. Dr. Netland believes reimbursement issues can be put in a more positive light. "I always encourage people to do something they enjoy, because financial rewards change over time," he says. "One subspecialty that gets high reimbursements may suddenly find them cut.

"In any case, I think glaucoma specialists do pretty well financially," he adds. "Here at the University of Tennessee, glaucoma is our most frequently coded diagnosis. It has an enormously beneficial financial impact on our ophthalmology group."

• Simplify care. Dr. Spaeth believes that simplifying care could help avoid a future public-health crisis. "We use much more technology than we need," he says. "More attention should be paid to taking the history, observing anterior chamber angles, the pupil and the optic nerve, and checking intraocular pressure. Should we be prescribing treatment to as many patients as we do? Our job isn't to prevent visual field loss, it's to prevent people from becoming disabled. If we disable them with the treatment, we haven't done a very good job.

"We need to think about these issues critically and train our fellows to do the same."

• Standardize training. Dr. Netland believes that future shortages can be prevented by increasing quality of care, as well as quantity. "Current training programs do a great job," he says, "but in many instances it's not clear what we expect trainees to know. It might be useful to continue efforts that have been started by the Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology and other groups, to try to develop minimal standards for what we're teaching."

Dr. Netland acknowledges that a change of this sort might not influence the number of residents choosing glaucoma, but it would have a good effect on the quality of graduating fellows. "A small number of well-trained people is sometimes more effective than large numbers of inadequately trained people," he notes.

• Train new doctors to fight for improvements in care. Given the number of people with glaucoma who are undiagnosed or receiving inadequate care, Dr. Spaeth believes that instilling a determination to innovate and be proactive about improving care could be a key factor in preventing future health crises. "We need to train doctors to be advocates for making the health-care system better," he says.

The Future Looks Bright

Despite the concerns about glaucoma as a subspecialty, Dr. Netland sees much reason to be optimistic. "This is an excellent time for residents to go into glaucoma," he says. "Everybody wants to be in a position where their skills are needed by society as a whole, and we're looking at an increasing need for glaucoma specialists. Anybody who trains in glaucoma should have a satisfying career."

1. Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O'Colmain BJ, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:532-538.

2. Gedde SJ, Budenz DL, Haft P, Tielsch JM, Lee Y, Quigley HA. Factors influencing career choices among graduating ophthalmology residents. Ophthalmology 2005;112:7:1247-54.