Here is what several refractive experts think about this practice and the results some of them are achieving with it.

A New Wrinkle in the Sheet

New Orleans surgeon Marguerite McDonald has been pleased with epi-LASIK's performance thus far, but is always interested in honing it further.

|

| Epi-LASIK may protect the stroma during healing better than PRK. All images: Manfred Tetz, MD |

"I think that, theoretically, there are many strong scientific underpinnings as to why epi-LASIK might be better than any other surface procedure," she says. "The main one is that, by leaving the living, though fatally injured, sheet of cells over the ablated area, by the time the cells actually die about five days later the underlying stroma will have long since passed its stage of vulnerability to all those pro-inflammatory cytokines. During normal PRK, though, the cell membranes rupture because the surgeon has used the Amoils brush or a spatula to remove the epithelium, and there is an immediate release of these pro-inflammatory cytokines from the billions of cells that are crushed. This release can lead to, in some cases, haze and regression. But now it seems some experts differ on whether you should keep the sheet or toss it."

Eric Donnenfeld, MD, co-director of the cornea/external disease department of the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital, took part in a controlled, 20-patient (40 eyes) study comparing traditional epi-LASIK to both PRK and epi-LASIK with removal of the sheet (called lamellar epithelial debridement in the study).

"The results of the study are that removing the flap gave the fastest visual rehabilitation, faster than either epi-LASIK or PRK," says Dr. Donnenfeld. "And we hypothesized that this is because the regular borders of the epithelial flap create a more rapid and smooth re-epithelialization, and we don't get that healing suture line through the visual axis that we see so commonly with PRK. So, if someone wants to see as quickly as possible with surface ablation, removing the flap is the fastest way. As far as the most comfortable way of doing surface ablation, epi-LASIK was more comfortable in the study than either PRK or lamellar epithelial debridement. Lamellar epithelial debridement was more comfortable than PRK."

Specifically, at day one, the average pain score was a three for epi-LASIK on an increasing pain scale from one to 10. It was 4.5 for lamellar epithelial debridement and about a 6.5 for PRK. On day three, epi-LASIK and lamellar epithelial debridement had the same level of pain. The return of visual acuity was about two days faster with lamellar epithelial debridement than with the other surgeries, and the epithelial defect healed about 18 hours faster with LED than with PRK. "After it healed, the surface was more regular than with PRK," says Dr. Donnenfeld. "I think this was because of the more regular borders of the flap."

Barrie Soloway, MD, director of vision correction surgery at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, prospectively studied 14 patients in whom one eye underwent conventional epi-LASIK surgery and the other underwent epi-LASIK with removal of the epithelial sheet. The patients didn't know which eye was receiving which procedure.

In this small group, he noticed better vision in the very early stages in the conventional epi-LASIK eyes, as well as less pain. But he says things were about equal from three days postop onward, and at one month the vision was better in the sheet-removal eyes.

As for why there might be a difference between the modalities, Dr. Soloway agrees with the theory of Toronto surgeon Raymond Stein, who says that the epithelial separator leaves a very sharp, atraumatic delineation at the edge of the bed. "When you're doing PRK, and just scraping away the epithelium, you're kind of disturbing the edge, or heaping up a bit with the Amoils brush, so you don't have a very clean edge," says Dr. Soloway. "So, the current thought, which seems to make sense, is that the edge of the removed epithelium is like a perfect epithelial edge, so it heals more like a regular corneal abrasion than a debridement, in which the periphery is kind of irregular."

Lingering Questions

Though some of the initial, small-scale studies seem to show that there may be some type of positive effect of removing the epithelial sheet, surgeons may need more evidence to convince them to modify their epi-LASIK technique.

|

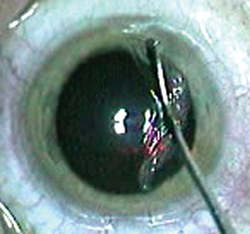

| Initial data shows that removing the epithelial sheet may speed recovery. |

"One of the issues we want to see resolved, and something we're going to be looking at for a longer term, is haze," says Dr. Soloway. "Originally, we thought one of the advantages of epi-LASIK was that we were covering the stroma and not letting the tear-film mediators get to the keratocytes and commence early activation of them, and we've had a low incidence of haze with flap replacement. So, there may end up being more haze with removal of the flap, but that may be a matter of 'only time will tell' at this point."

Berlin surgeon Manfred Tetz, one of the first surgeons to notice a beneficial effect of removing the epi-LASIK sheet, says that, to come to any conclusions, surgeons will have to analyze traditional epi-LASIK, specifically with regard to the contact lens used.

"If the epithelial flap on the eye is replaced and doesn't actually fit the bed," he says, "but is instead mobile beneath the contact lens, that may be causing the extra pain when compared to removing the sheet." He says this gives rise to the possibility that maybe the contact lens is contributing to the pain, and maybe surgeons should use lenses with a closer fit that don't allow the epithelial sheet to move.

Another issue that arises is this: If leaving the epithelial sheet off is beneficial, why not do PRK?

"A lot of surgeons' knee-jerk reaction when hearing this is, 'Why buy a $50,000 or $60,000 machine to take off the epithelium when I can do it by hand during a classic PRK?' " says Dr. McDonald. "The answer is this: Taking it off by hand or with the Amoils brush is like smashing a billion eggs— the contents, pro-inflammatory cytokines, drip downward instantly into the stroma. If you lift it off without disturbing the cell membranes and then amputate the sheet, all those inflammatory cytokines stay inside the cells and don't 'drip down' into the stroma." She says that current theory, supported by indirect evidence, holds that if the surgeon uses an epikeratome to lift the sheet and then reposits it after the ablation, the pro-inflammatory cytokines will leak out four to five days later, but it won't matter, as the stroma will have passed its moment of vulnerability.

Dr. Tetz also thinks there's a difference stemming from how the epithelium is removed in surface ablation cases. "The degree of hydration on the corneal bed makes a difference, too," he says. "When you debride epithelium with a hockey-stick shaped blade, you have some drier areas and some wetter areas, causing the epithelium to come off a bit sticky in areas where it's really dry or to be thicker in areas that are wetter. For me, the surface that I start treatment on after a keratome-created epithelial sheet is the smoothest possible, with an even hydration."