Cystoid macular edema is the most common cause of visual decline after uncomplicated cataract surgery and can have long-term consequences for patients. While CME typically responds to treatment, patients may still experience decreased contrast sensitivity after the CME has resolved.

Incidence and Causes of CME

The incidence of CME after routine cataract surgery has not changed in recent years, but surgeons are gaining a better understanding of its impact on patients and how to prevent its occurrence.

"Approximately 15 or 20 years ago when we were performing extracapsular surgery, we really never paid much attention to CME," says Henry D. Perry, MD, who is in private practice with Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island, Stony Brook, N.Y. "It was reported to occur angiographically in 20 percent of cases, but clinically significant CME was about 1 percent. When we started doing phacoemulsification, some of us thought that the incidence had decreased to a little less than 0.5 percent. However, we have now found that, angiographically, the incidence is still about 20 percent." Even a 1 percent clinical CME incidence still represents 28,000 new cases annually in the

Whether the incidence of CME has changed or not, its diagnosis is evolving. "In the past, CME was diagnosed when surgeons could actually see it clinically during an examination or when it could be seen with fluorescein angiography," says

Today, CME can be diagnosed using optical coherence tomography, which is a much less invasive test. "Unless you routinely use OCT, you will not detect subclinical CME, which is often asymptomatic," says David F. Chang, MD, a clinical professor at the

A study conducted by Calvin Roberts, MD, found that, even when a patient shows no change in Snellen visual acuity, there may be low levels of post-cataract CME and decreased contrast sensitivity.1

When diagnosed, CME can be treated aggressively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids; however, treatment is not ideal. While these patients typically regain their visual acuity, their contrast sensitivity continues to be affected. This is especially difficult for patients with multifocal IOLs, which are sensitive to any loss in contrast sensitivity.

Additionally, managing CME is associated with substantial costs. A recent study analyzed the cost of treating CME in the United States using Medicare data from the 1997 through 2001.2 When comparing the patients who were diagnosed with CME with patients who were not diagnosed with CME, the investigators found that annual total ophthalmic claims were 41 percent ($3,298) higher for patients with CME and the payments were 47 percent ($1,092) higher.

Because treating CME after it occurs has both visual and financial implications, it is important to take steps to prevent CME in routine cataract patients.

Preventing CME with NSAIDs

For the past few years, surgeons have had a number of topical NSAID options, including Acular, Acular PF and Acular LS (ketorolac tromethamine), Ocufen (flurbiprofen sodium) and Voltaren (diclofenac sodium). More recently, Xibrom (bromfenac) and Nevanac (nepafenac) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use during cataract surgery.

A number of studies have shown that the use of NSAIDs preoperatively can reduce the incidence of both subclinical and clinical CME. For example, Dr. Roberts' study tested 200 patients who underwent routine phacoemulsification and were randomized to one of two regimens: a topical antibiotic, topical steroids and a topical NSAID (ketorolac tromethamine); or a topical antibiotic and topical steroids, but not a topical NSAID.1 Patients' macular thickness was determined pre- and post-surgery with OCT. Contrast sensitivity was measured one month postoperatively. The results showed that patients who did not receive a topical NSAID had macular swelling and decreased contrast sensitivity.

A more recent study conducted by John R. Wittpenn, MD, and colleagues found that ketorolac 0.4% significantly reduces the incidence of CME and maximizes the potential of an excellent visual result, even in low-risk cataract patients (Wittpenn J, et al. IOVS 2007; 48:ARVO E-Abstract 5464).

The study was designed to assess the risk of developing CME in cataract patients with no identifiable risk factors for CME," says Dr. Wittpenn, who is in private practice at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island,

He says that he wanted to determine these patients' risk of developing CME and whether that risk could be reduced or eliminated by using nonsteroidals. Patients who experienced complications during surgery and patients who had excessive amounts of inflammation on the first postoperative day were excluded from the study.

In this investigator-masked, multicenter clinical trial, 546 low-risk patients were randomized into two groups. Half of the patients received ketorolac 0.4% four times daily for three days prior to surgery and four doses during dilation immediately before the procedure. These patients also instilled prednisolone four times daily from a 5-ml bottle until empty, and they continued to use ketorolac four times daily until they exited the study. The other group of patients received a tear dilution for three days prior to surgery, and they only received four doses of ketorolac 0.4% during dilation immediately before the procedure. These patients continued to use the tear solution four times daily until the bottle was empty. They also instilled prednisolone four times daily from two 5-ml bottles until exiting the study. Patients attended follow-up study visits on day one and between days eight and 12 (week one) and between days 26 and 34 (week four) postoperatively. Retinal thickening was measured by OCT preoperatively and at the week one and week four follow-up visits.

The study found that the use of ketorolac 0.4% significantly reduced the incidence of retinal thickening and CME. In fact, 73.6 percent of patients who were given ketorolac 0.4% preoperatively had retinal thickening of less than 10 µm, compared with 50.8 percent of patients who were given the tear solution. Additionally, patients given the tear solution were more likely than patients given ketorolac 0.4% to have retinal thickening of more than 10 µm (49.2 percent compared with 26.4 percent), more than 15 µm (31.4 percent compared with 17.4 percent), or more than 25 µm (11.5 percent compared with 8.4 percent). The patients given the tear solution were also more likely than the patients given ketorolac 0.4% to have CME as diagnosed by a masked retinal specialist. The study also found that there was a trend toward worsening visual acuity with increased retinal thickening.

"In the routine cases, ketorolac 0.4% appears to eliminate CME if the patients are compliant. It also significantly reduces the risk of macular thickening and a decline in contrast sensitivity in a high percentage of patients," Dr. Wittpenn explains.

A study conducted by Eric D. Donnenfeld, MD, and colleagues yielded similar results.3 In this study, 100 patients were randomized in a double-masked fashion to four groups: 25 patients received ketorolac for three days before phacoemulsification; 25 patients received ketorolac for one day before phacoemulsification; 25 patients received ketorolac one hour before surgery; and 25 patients received a placebo. All patients in the treatment groups received ketorolac 0.4% for three weeks postoperatively. Patients in the placebo group received vehicle. In this study, none of the patients receiving ketorolac for one or three days before surgery developed CME, compared with 12 percent of patients in the control group and 4 percent of patients in the one-hour group.

Newer NSAIDs

Other nonsteroidals, such as nepafenac and bromfenac, have also been shown to prevent CME. In fact, after reviewing three recent clinical trials of nepafenac 0.l%, Richard Lindstrom, MD, and Terry Kim, MD, concluded that nepafenac 0.1% may play a role in preventing conditions such as CME.4 Their review found that nepafenac has the ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in the posterior segment; therefore, it may have a clinical role in CME. "Cataract patients often take three medications following surgery (an antibiotic, a steroid and an NSAID), so compliance can be an issue," says Dr. Lane. "Because of the comfort upon instillation with nepafenac, I find compliance with this NSAID to be excellent."

Dr. Chang adds, "I have found that ketorolac, nepafenac and bromfenac work equally well for CME prophylaxis. For patients in whom compliance with medications is difficult, bromfenac has the advantage of twice-daily dosing."

Another study is ongoing, with its initial data having been presented last year.5 The study is comparing the efficacy of bromfenac 0.09% (Xibrom), a b.i.d-dosed topical NSAID, against diclofenac sodium 0.1% (Voltaren) and ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% (Acular), two q.i.d dosed NSAIDs with known efficacy in the treatment of acute pseudophakic CME, using visual improvement as evidence of treatment efficacy (See Table 2, below). The study's lead author consults for Ista, maker of Xibrom.

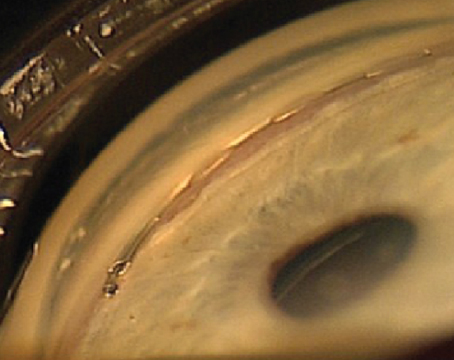

In the study, 85 patients with acute CME following uncomplicated cataract surgery were randomized to treatment with one of three regimens: 47 patients were treated with bromfenac 0.09% b.i.d.; 18 patients were treated with diclofenac sodium 0.1% q.i.d.; and 20 patients were treated with ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% q.i.d. in the affected eye. Open label, branded medications were used exclusively. CME was confirmed by fluorescein angiography, ocular coherence tomography or both. Patients were examined monthly, with visual acuities measured by Snellen and ETDRS charts.

Exclusion criteria included the following: complicated cataract surgery, particularly posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss; pre-existing macular pathology, including macular edema, macular scar, macular hole, or macular pucker; history of uveitis; ipsilateral intraocular surgery prior to cataract surgery; and CME greater than one year duration.

The researchers concluded that bromfenac 0.09% dosed b.i.d was as effective as either diclofenac sodium 0.1% or ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% dosed q.i.d in the treatment of acute pseudophakic CME following uncomplicated cataract surgery.

A New Standard?

Many cataract surgeons consider preoperative nonsteroidal use to be standard of care. In a recent commentary, Terrence P. O'Brien, MD, discussed guidelines for using NSAID therapy in routine cataract cases.6 "Topical NSAID dosing (one to two days preoperative prophylaxis and three to four weeks postoperative prophylaxis) is recommended to provide routine appropriate protection against CME for those patients at low risk for postoperative CME," Dr. O'Brien says.

"I have been using nonsteroidals before and after surgery for approximately eight years," says Dr. Perry, who is associate clinical professor, Weill Medical College of Cornell University in

Dr. Lane also starts his routine cataract surgery patients on nonsteroidals three days before surgery, but he continues their use for four to six weeks postoperatively. "Postoperatively, I use OCT anytime I feel that the patient's vision isn't as good as I would expect it to be," he says. "If a patient develops CME after routine cataract surgery, I treat him or her with nonsteroidals postoperatively along with topical steroids. I will treat the patient for several weeks and then see him again to see if there has been any change or improvement. If I'm not making any headway with treatment, I will often refer the patient to one of my retina colleagues for evaluation for intraocular injection."

Dr. Chang starts NSAIDs the day before surgery and continues their use for approximately one month after surgery. He uses them in conjunction with a topical steroid.

In addition to preventing CME, NSAIDs may provide some additional benefits both during and after surgery. The preoperative and postoperative use of NSAIDs can help to manage pain and inflammation and can accelerate the return of visual acuity in cataract surgery patients. Additionally, use of NSAIDs keeps pupils dilated during surgery, which allows for quicker and less traumatic procedures.

Beyond NSAID Use

Impeccable surgical technique can also lower patients' risk of developing CME postoperatively. "During surgery, keep the light at a lower intensity," Dr. Perry says. "In the 1970s, a study showed that increased light intensity at surgery is associated with macular changes. Additionally, any kind of complication, such as a ruptured capsule, leads to a significantly increased risk of CME, so avoiding complications is a big help."

Dr. Lane agrees, noting that it is also important to ensure complete removal of the lens material, which can help to decrease the potential for inflammation after surgery.

"In otherwise uncomplicated cases, excessive iris manipulation and residual cortex are two operative factors that increase the risk of CME," Dr. Chang adds.

1. Roberts CW. NSAID to decrease postoperative macular edema. Presented at the 2005 ASCRS meeting in

2. Schmier JK,

3. Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD, Wittpenn JR, Solomon R, Nattis A, Chou T. Preoperative ketorolac tromethamine 0.4% in phacoemulsification outcomes: pharmacokinetic-response curve. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32(9):1474-1482.

4. Lindstrom R, Kim T. Ocular permeation and inhibition of retinal inflammation: an examination of data and expert opinion on the clinical utility of nepafenac. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22(2):397-404.

5.

6. O'Brien TP. Emerging guidelines for use of NSAID therapy to optimize cataract surgery patient care. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21(7):1131-1137.