The Nature of the Problem

After determining basic facts such as the type of multifocal lens the patient has and specifically the reading add power, I ask several key questions:

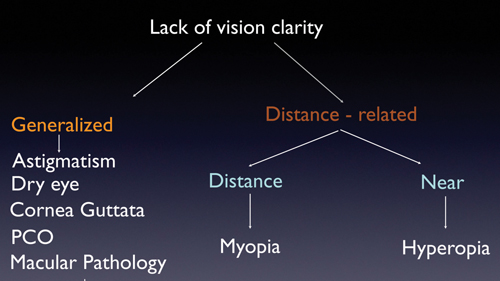

• Is the complaint a lack of visual clarity or is it a specific type of visual disturbance such as glare, halo or starbursts? Making this differentiation is important since the former symptom is multifactorial but many causes are treatable.

• If it’s a lack of clarity, is the problem specific to one viewing distance or is it present at all distances? The thought process here is that, if the patient’s problem is specifically related to one particular viewing distance, the etiology of the problem is usually a refractive error such as residual myopia or hypermetropia. Once this is identified, it is important to determine if the patient’s lack of clarity is much improved by placing a refractive correction. Ensuring this suggests that surgical correction of the refractive error is likely to help.

The other aspect of problems along these lines is that, sometimes, a patient will have a multifocal lens and will discover that it isn’t easy to see at the intermediate distance. This issue is particularly common with the Tecnis multifocal lens, which only has a strong +4 add in the United States. With that lens, intermediate vision tasks are sometimes only clear if the patient moves closer to the object of regard, such as the computer screen or other intermediate target. Because of this, it’s important to determine if the difficulty a patient is having is related to the distance he needs to be from the target. For instance, say a patient has a Tecnis multifocal intraocular lens and is having a problem with the computer. If, in trying to characterize the problem, you find out that the patient is actually saying he can’t see the screen from the usual distance but can see it when he moves closer, that’s something that you know is simply a function of how the lens operates. Knowing this, you can explain the situation to the patient and then design a pair of eyeglasses that can counteract the problem.

A lack of clarity at all distances could be the result of various other factors, some of which are further elaborated below.

• How long has the patient had the symptoms or lack of clarity? If the patient’s problems started literally from the get-go after cataract surgery, that’s an important fact to know. This is because the reasons why such instant problems could be occurring are slightly different from those behind problems that occur after a few months or years of having the lens. The latter case is suggestive of an acquired cause for the unhappiness and, in many cases, an acquired cause is treatable.

|

• Is the lack of functionality or clarity dependent on the amount of light available? Most of the currently available multifocal lenses are dependent on pupil size and the amount of light available for reading. So, when the light is good and the pupil is small, that facilitates reading with some of the multifocal lenses. Knowing this can help you differentiate between problems that you can actually solve and those that are simply endemic to using a particular lens. For example, if a patient with a ReSTOR lens complains that he can’t read in a dim light situation such as in a restaurant, you can’t change or help that situation. That is simply the nature of how the refraction works with such lenses.

Exam Notes

In addition to a careful history, here are ways to approach the physical exam that can yield helpful diagnostic information.

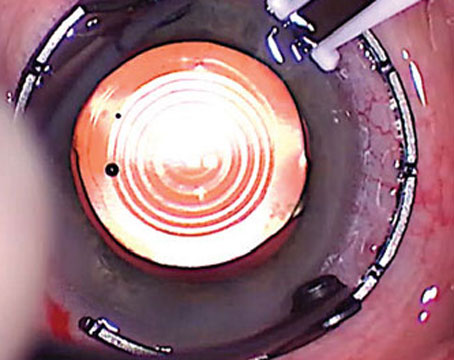

• Refraction. In a patient with a multifocal lens, the retinoscopic reflex can be confusing, because you have different reflexes coming from different areas of the lens. When performing a refraction then, focus right in the center of the lens where there is a small area with no multifocal rings. Doing that will provide a clue to the real refractive error in these patients.

I like to test the vision at all distances. This helps me understand straightaway what the patient can and can’t do easily. For instance, if he can read 20/20 at distance but doesn’t do well at intermediate or near, I then suspect that he may have a small amount of hypermetropia that he’s able to counter well at a far distance but not at the other distances.

• Slit lamp exam. At the slit lamp, I like to focus on four things. First, I assess the status of the tear film and the ocular surface. Are there dry spots on the cornea? What is the quality (assessed by tear-film breakup time) and the quantity (assessed via Schirmer’s) of the tears? If one or both of these tests is sub-optimal, you can get dry-eye-related vision difficulty. A low Schirmer’s test and dry spots on the corneal surface tell you that the patient’s volume of tears is low. A very rapid tear-film breakup could be due to a low tear volume, but it could also be due to meibomian gland dysfunction. So, if you see a very rapid breakup, look at the Schirmer’s result. If the Schirmer’s was normal then home in on the meibomian gland, focusing on the gland secretions. If the meibomian gland secretions are very thick, they could cause a rapid breakup, which could result in suboptimal vision.

The second structure to focus on is the endothelium. If there are guttata, that can be an important cause of poor visual quality.

The third important consideration is the position and centration of the IOL, for obvious reasons. If the lens isn’t well-centered, the patient won’t be able to get the best vision from it.

Finally, check the status of the posterior capsule, which really needs to be clear in order to get good quality from these multifocal lenses.

• Pupil examination. Of the three aspects of the pupil exam—size, centration and angle kappa—pupil size is the most important in the unhappy multifocal lens patient. This is because most surgeons know that if the pupil is grossly decentered the multifocal patient obviously is not going to be happy. More to the point, most surgeons wouldn’t have implanted one of these lenses in that kind of patient in the first place. The impact of pupil size, though, is very easy to miss if you didn’t specifically look for it preoperatively.

For multifocal IOL patients, in order to see well at distance, especially in dim light while driving, for example, the pupil needs to get to its normal physiologic size in dim light, which is 5 to 6 mm. However, in order for a multifocal lens to allow a patient to read, the photopic pupil size should be close to 3 mm. From time to time, though, we will encounter a patient whose pupil doesn’t come down that much and, because of this, you can expect that the reading ability won’t be as good in that patient if he has a multifocal lens. On the other hand, some elderly patients will have pupils that don’t dilate as widely as they should, and they may be unhappy with their nighttime driving vision due to decreased clarity. Therefore, you will be able to surmise that the patient’s problem isn’t a visual disturbance but is instead a pupil-related difficulty with distance vision in dim light, which may be helped with a dilute mydriatic.

• Corneal topography. Pay attention to indices that are available on many topographers such as the surface regularity index and the surface asymmetry index. In some cases, you may see some dry eye or basement membrane dystrophy, but the impact of these is more obvious when you use one of these indices. Topography is also very useful for getting a sense of the astigmatism, since the most common cause of unhappiness in premium lens patients is some sort of residual refractive error, including cylinder.

• Macula exam. I have a low threshold for doing optical coherence tomography in these patients, and will do OCT on anyone who’s unhappy, because macular changes are a critically important cause of poor vision after a premium IOL. It’s not uncommon to miss a subtle epiretinal membrane on ophthalmoscopy but then find the wrinkling caused by the ERM to be obvious on OCT.

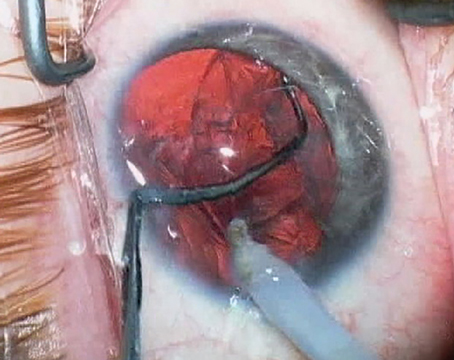

Though patients’ complaints following multifocal IOL implantation can be caused by a number of factors, if you take a logical, stepwise approach, you’re likely to frame the problem properly and take the right steps toward a solution. There is clearly a small subset of patients who will need IOL exchange, but by taking a systematic approach you can identify and correct those that can be treated without intraocular surgery. REVIEW

Dr. Basti is a fellowship-trained specialist in refractive, corneal and cataract surgery and is an associate professor of ophthalmology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.