|

At the recent American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting, the American Society of Retina Specialists presented the results of its most recent Preferences and Trends survey.1 The survey was given electronically to 2,971 members of the society (2,615 regular members and 356 fellows); 1,057 respondents completed the survey (35-percent response rate). The survey is an interesting snapshot of retina specialists’ approaches to various clinical and surgical situations.

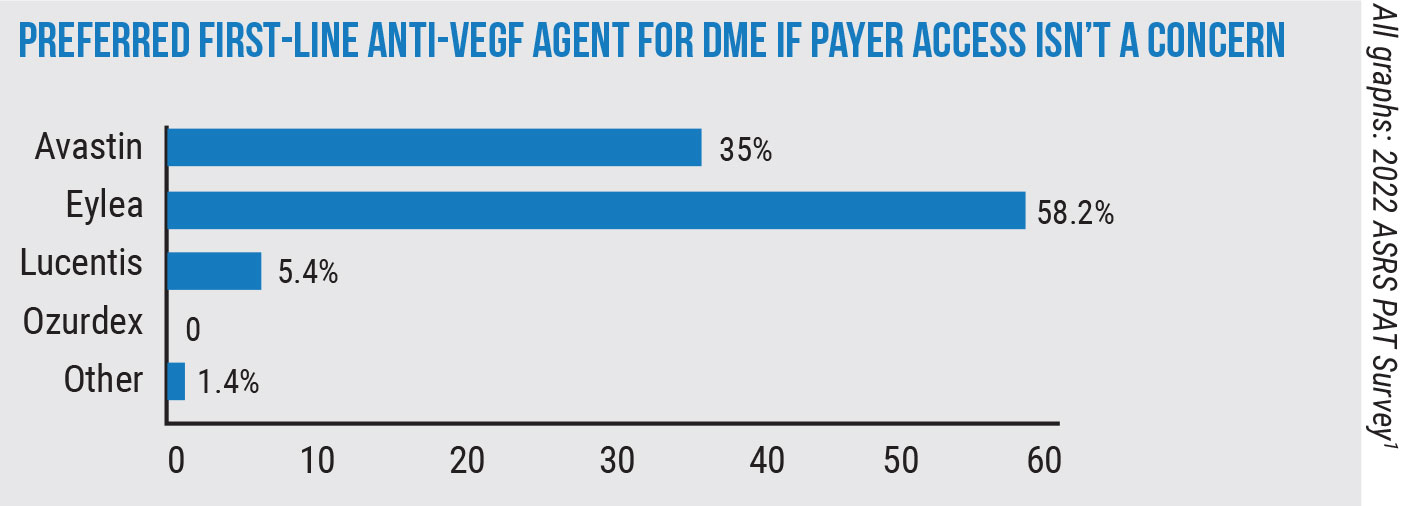

The management of age-related macular degeneration is always a focal point of the survey. For wet AMD patients who have a suboptimal response to Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech) treatment, 88.4 percent of the physicians say they’ll switch to Eylea (aflibercept, Regeneron). A smaller percentage, 11.1, say they’ll switch to Lucentis.

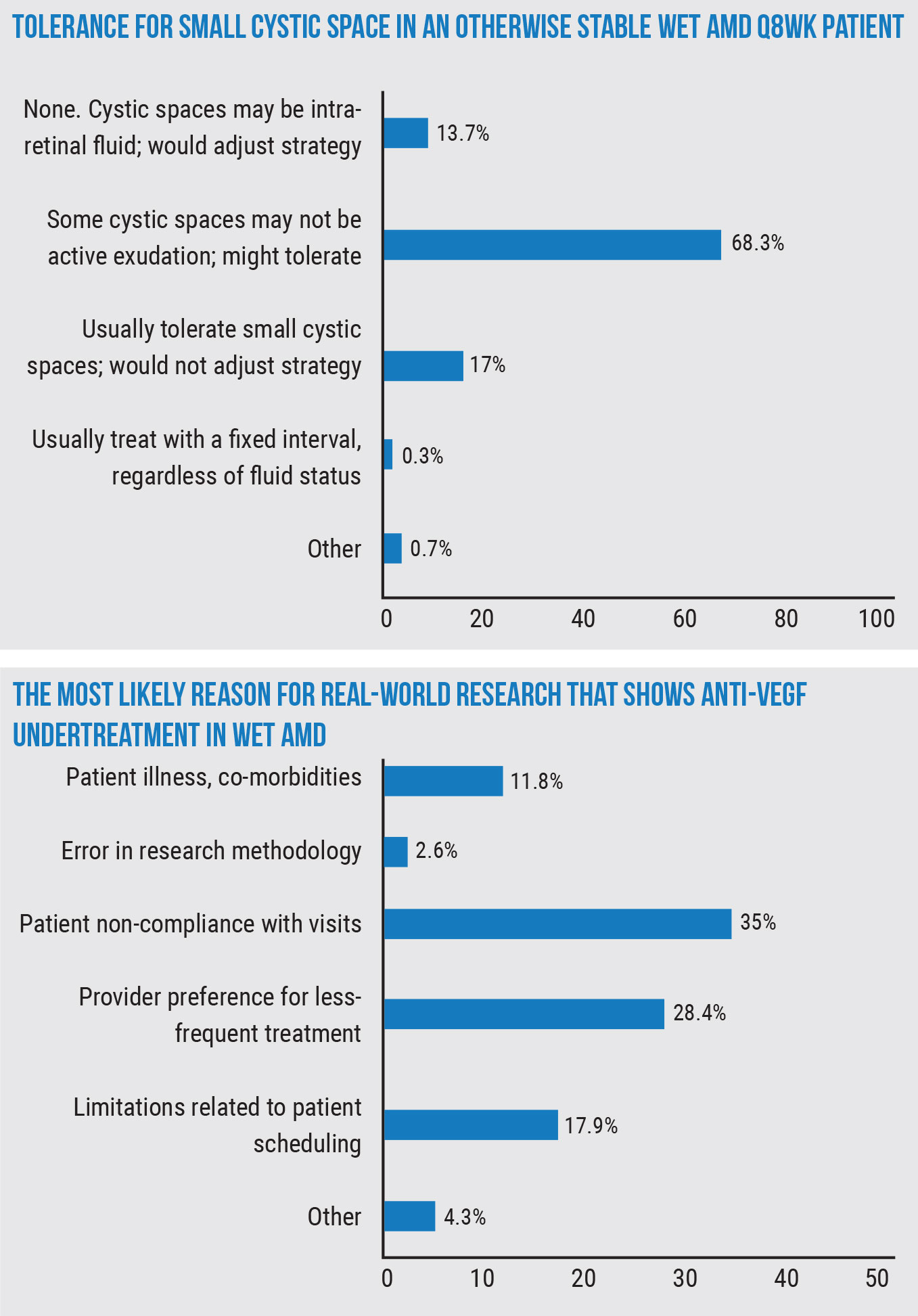

In the course of treating these wet AMD patients, a point that’s often raised is what to do if some fluid still exists, and surgeons were asked their level of tolerance for a small cystic space on OCT in a patient who had long been stable during an eight-week anti-VEGF regimen (the vision is good and symptoms remain unchanged). Most respondents, 68.3 percent, say, “Some cystic spaces may not represent active exudation; might tolerate,” 17 percent say they “usually tolerate small cystic spaces and wouldn’t adjust their strategy,” and 13.7 percent say they have no tolerance for any fluid and that cystic spaces may represent intraretinal fluid, so they’d adjust their strategy.

Los Angeles retina specialist David Boyer says this approach jibes with what he’s seen. “We’ve learned over the years that some of these small cystic spaces are really intraretinal degenerative cysts and aren’t part of leakage,” he says. “If we have a patient with a few of these cysts, it may just be degeneration of the retina and not active leakage. The same goes for subretinal fluid: We try to treat it to dry it out, but we’ll tolerate some small amount of subretinal fluid; it may turn out to be beneficial to the photoreceptors at this point.”

|

Retina specialists have one eye on the future however, and are interested in new therapies: In response to the interesting question, “In what percentage of your currently treated wet-AMD patients are you (or your patient) actively seeking improved outcomes (e.g., longer duration or improved efficacy) not provided by current anti-VEGF options?” 24 percent say more than half of their patients are looking for improved methods, 22.2 percent said between fully 26 and 50 percent are looking for something new, and 27.7 percent said between 11 and 25 percent are looking for improved outcomes of some sort.

Dr. Boyer says he thinks the number of patients and doctors looking for better options is probably even higher in diabetic retinopathy. “In diabetes, there are many times that I have to switch drugs, add a medication or use a steroid,” he says. “That’s why we’re looking for other treatments with different modes of action. Perhaps Vabysmo may be better; we’re also getting longer-acting steroids and, hopefully, some of the plasma kallikrein inhibitors may improve results in some of the diabetic retinopathy patients with persistent fluid.”

The survey also asked respondents their thoughts on why it appears that real-world research studies often report undertreatment with anti-VEGF agents for wet AMD. The most popular reason given was patient non-compliance with visits, at 35 percent, followed by “provider preference for less-frequent treatment” at 28.4 percent. (The other reasons appear in the graph, below right.)

“The reason for [undertreatment in real-world studies] is multifactorial,” Dr. Boyer says. “Patients wear out. They don’t want to come in as often. Study patients are highly reliable and aren’t the average patient. In studies, you’ll see more than 90 percent of people receiving the proper amount of medication. In patients we’re treating, these lesions are often big, and patients will drop out or try to reduce the treatment frequency. A doctor who’s busy may often try to push the envelope and push the injections out an extra week or week-and-a-half. Also, I think a lot of people are using treat-and-extend. So, you have approximately 75 percent of patients who can go three to four months [between injections], so if you look at it compared to the treatments in the studies where you were mandated to administer treatment either monthly or every two months, you’re going to be way under. It doesn’t seem to be economics because Pfizer had the same exact result as the studies that pooled Medicare databases.

“Using the studies as a baseline isn’t the best way of following these patients,” he continues. “It would be best to look at the small studies where they used treat-and-extend and saw the results are good with minimizing the amount of treatment. I think 80 percent of physicians use treat-and-extend.”

A question that often arises in panel discussions, and which also appeared on the survey, is how to handle the diabetic retinopathy patient with peripheral non-perfusion on fluorescein angiography but no neovascularization or diabetic macular edema. On the survey, 45 percent of the respondents said they’d monitor the patient every three months, 26 percent would perform panretinal photocoagulation, 12.6 percent would monitor every one to two months, 9.9 percent would administer an anti-VEGF injection and PRP, 4.6 percent would use an anti-VEGF injection alone, and 1.8 percent would take some other course of action.

“These are patiens that a lot of people will follow carefully every three months looking for signs of active proliferation,” Dr. Boyer says. “We see non-perfusion very commonly in these patients, and we haven’t done a study in these patients without neovascularization to see if laser will make a difference. Obviously, however, if you have a non-compliant patient and they’re lost to follow-up—they are getting sick or lose their insurance and can’t come back in a year—they can return to your office and look terrible. I think this type of treatment or observation decision really depends on the compliance of the patient and what their A1C is. If someone comes in and their A1C is 9 or greater, they’re probably not a compliant patient and you probably want to be more aggressive to prevent vision-threatening complications in the long run. But if their A1C is 7.5 or below, you know they’re somewhat compliant and will come back, so you may want to watch them until they reach a certain threshold. I can’t fault anyone for treating these patients with the idea that if they get lost to follow-up they can do very poorly. On the other hand, I can’t fault someone who says, ‘I’m just going to watch them until they develop high-risk characteristics and then treat them at that point.”

In something of a sea change, treating patients’ vitreous floaters is no longer taboo: Forty-nine percent of the respondents say they perform one to three vitreous-opacity surgeries each month, 4.2 percent do four to six, 2.1 percent perform seven to nine and 0.8 percent do 10 or more. Forty-four percent don’t perform them.

“I’m not surprised,” says Dr. Boyer. “In the past, floaterectomy surgery was looked at as outside the norm. Now, however, the most common question I’m asked after removing floaters is, ‘When can you do my other eye?’ In these patients who are really bothered, the vitreous gel can, in some cases, reduce their dark adaptation.

“Obviously, it involves risks,” he continues, “but they appear to be minimal if you don’t start doing things like peeling the ILM and all you do instead is just go in and remove it. As surgeons gain more confidence and realize what they’re doing really does help the patient, I think you’ll see this increasing over time despite the fact that it’s surgery. These floaters are really a problem for some people.”

1. Poster presentation: 2022 ASRS PAT Survey. American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting. Chicago, 2022.

Genetech/Roche Susvimo Implant Recalled

Around this time last fall, the FDA approved the first sustained-release drug delivery system for wet AMD, the intravitreal implant Susvimo (100mg/mL ranibizumab injection, Genentech/Roche), a novel treatment approach requiring a medication refill only every six months. Fast forward to this year and the product is being pulled from U.S. shelves due to a voluntary manufacturer recall relating to a potential leakage problem.

Between twice-yearly treatments, the implant is designed to dispense the anti-VEGF agent into the vitreous in a controlled manner. However, on Oct. 18, Roche CEO Bill Anderson explained in an investor call that, due to a manufacturing issue, the company has cause for concern that there may be a problem with the seal on the intravitreal device that’s intended to prevent the medication from leaking out after it’s injected. As reported in the industry publication, Fierce Pharma, Mr. Anderson communicated Roche’s concern about the possibility that the seal could fail after repeat dosing and is quoted as saying, “because it didn’t meet our performance standards, and [because] we want to make sure that we have high reliability, we decided to voluntarily stop distribution of the port delivery system.”1

Roche advises patients who already have the Susvimo implant to continue receiving refills as normal, and notes that explantation is not necessary. However, no new patients will be able to receive the implant until the production issues are resolved and the device returns to the market, which the company estimates will be approximately within a year or so.

1. Kansteiner F. Roche recalls new eye therapy Susvimo on leakage fears, aims for market return ‘within a year or so’. Fierce Pharma. Published October 18, 2022. https://www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/roche-recalls-susvimo-implant-lucentis-leakage-fears-return-market-expected-within. Accessed October 19, 2022.