Part one (June 2009) of this article on inflammatory chorioretinopathies of unknown etiology, also called "white dot syndromes," focused on acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome and serpiginous choroiditis. This installment will conclude the review of these common uveitic entities that affect relatively young, otherwise healthy patients.

Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy

Birdshot retinochoroidopathy, also called vitiliginous chorioretinitis, is a bilateral inflammatory chorioretinopathy that usually affects healthy men and women in the fourth to sixth decade of life.1,2 Ninety percent of patients who have birdshot retinochoroidopathy are HLA-A29-positive.1-3 There is some clinical evidence to suggest that this is an autoimmune disease, since affected patients may have lymphocyte reactivity to retinal S-antigen.3

Patients who develop birdshot retinochoroidopathy often complain of floaters, blurred vision and photopsias, and much later in the course of the disease development, nyctalopia and macular color blindness.1 Vitritis is often present, and multifocal depigmented patches are present at the level of the choroid and choriocapillaris throughout the posterior pole, typically in a radiating fashion away from the optic nerve.

The creamy, white-to-yellow lesions are typically small and less than one disc diameter in size, but are numerous (See Figures 1a & b).1,4 This fundus appearance looks similar to the buckshot fired from a shotgun and gives the disease the clinical name birdshot.

The diagnosis of birdshot retinochoroidopathy is based on the age of onset combined with the clinical appearance, ocular findings and HLA-A29 positivity. Fluorescein angiography reveals disc leakage and cystoid macular edema, which is a common complication in patients with birdshot retinochoroidopathy.3

Electroretinography is useful as a way to establish diagnosis and follow progression of disease. Moderate-to-severe depression of rod and cone function may be noted in active disease. Severe cases may be associated with an extinguished electroretinogram.4-6

The differential diagnosis of birdshot retinochoroidopathy includes pars planitis, idiopathic chronic iridocyclitis, papilledema, intraocular lymphoma, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, MEWDS, ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, sympathetic ophthalmia and sarcoidosis.

Patients who have birdshot retinochoroidopathy can be treated with oral, systemic or paraocular corticosteroids, but long-term treatment with immunomodulatory therapy is required.5,6 Even with long-term therapy, however, the disease will continue to progress albeit at a slower rate. The long-term visual prognosis is at best guarded for patients who have birdshot retinochoroidopathy.6 Serial electroretinograms performed every six to 12 months that follow B-wave amplitudes and implicit times along with automated visual field testing have been promoted for gauging progression of this disease process.5.6 Chronic cystoid macular edema may result in permanent vision loss.4

MCP

Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis syndrome is a relatively common inflammatory disease that occurs predominantly in women in the second to sixth decade of life.10,11

Most cases are bilateral or become bilateral over time. Patients often present with decreased vision in one or both eyes. Photopsias may be present along with an enlargement of the physiologic blind spot.10-13 Patients may have variable amounts of anterior segment inflammation and vitritis. Acute choroidal lesions may appear white to yellow and may be associated with overlying vitritis and may range in size from 50 to 350 µm. They may number up to several hundred throughout the retina and they can occur in linear clusters or streak lesions as well. As these lesions age and become inactive, they become atrophic and "punched-out" (See Figure 2).10,11,14,15 Over time, peripapillary scarring and atrophy may develop, and peripapillary and macular choroidal neovascularization may occur in one-quarter to one-third of patients; this is a major cause of vision loss in MCP.10,11,12,15

The diagnosis is made by clinical examination but, as in other cases of multifocal choroiditis, other entities must be ruled out with appropriate laboratory testing.

Subretinal proliferation of pigment epithelium with fibrosis and clumping is much more common with multifocal choroiditis than with ocular histoplasmosis syndrome.

Fluorescein angiography usually reveals early blockage by acute active lesions in the choroid with late staining of these lesions.10,11 Atrophic lesions appear hyperfluorescent in the early phases and fade in the late phases of the angiogram.

Peripapillary or macular choroidal neovascularization and cystoid macular edema may be identified clinically and angiographically in some patients.10,11 ICG angiography may demonstrate multiple hypofluorescent spots compatible with active choroiditis around the optic disc. Visual field testing may reveal an enlarged blind spot.10-13

Differential diagnosis includes ocular histoplasmosis syndrome which invariably has no associated vitreous inflammation,15 sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, sympathetic uveitis, subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome, serpiginous choroiditis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy and myopic degeneration.

There have been systemic associations of multifocal choroiditis including Epstein-Barr virus infection, however, this is controversial and not proven.16,17

Treatment of multifocal choroiditis with panuveitis is with topical, regional or systemic corticosteroids.10,11,15 Choroidal neovascularization may be treated with a combination of systemic, intraocular and paraocular corticosteroids, and laser photocoagulation treatment, photodynamic therapy or anti-VEGF agents.10,11,15,18 Occasionally, subfoveal choroidal neovascularization may be removed surgically if the vascular in-growth site is located outside of the foveal avascular zone.

Multifocal choroiditis has a waxing and waning course and progressive loss of vision may occur; and corticosteroids alone may be insufficient to control intraocular inflammation.10,11 If there is extensive fibrosis that occurs with this syndrome, this may spill over into the development of progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome.

It is felt by many investigators that these two diseases may actually represent a spectrum of the same disease process.12,13

SFU

Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome is an extremely rare entity and usually affects young women in the second to third decades of life who otherwise have no other systemic health problems.7,8 The condition is associated with significant anterior segment inflammation combined with severe chronic vitreous inflammation and white, fibrotic, subretinal lesions that largely coalesce in a progressive manner to involve most of the retina and choroid (See Figures 3a & b). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic ophthalmic appearance. Laboratory testing is unrevealing.

Differential diagnoses include sarcoidosis, onset histoplasmosis syndrome, toxoplasmosis and retinochoroiditis, multifocal choroiditis and birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Histopathologically, this condition is associated with predominance of B-cells and plasma cells and subretinal fibrotic tissue with islands of retinal pigment epithelial and Müller cells.9

Treatment requires the use of one or more systemic immunomodulatory agents. The visual prognosis is poor.7,8

PIC

Punctate inner choroidopathy is often confused with multifocal choroiditis.19 It is a bilateral inflammatory disease that affects young, otherwise healthy, myopic women.19

Patients usually present with photopsias, blurred vision and metamorphopsia or paracentral scotoma. Patients have little to no anterior segment or vitreous inflammation.

Ophthalmoscopic examination usually reveals small, white-yellow lesions at the level of the choroid and pigment epithelium that surround the disc and the macular region (See Figures 4a & b). A serous retinal detachment may be present overlying the active lesion (See Figure 5a). The lesion heals as atrophic scars with very little pigmentation.

Choroidal neovascularization can develop commonly in up to one-third of patients and usually develops from healed or atrophic scars (See Figures 4a & b).19

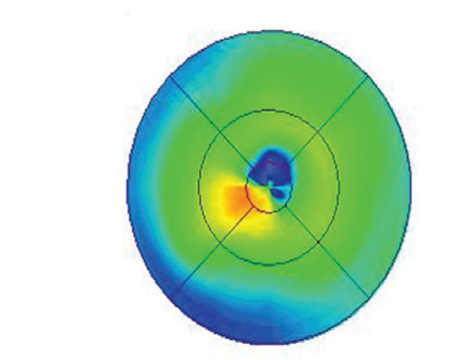

The diagnosis is based on typical ocular findings. Fluorescein angiography of acute lesions shows early hyperfluorescence and late leakage of active lesions with pooling of fluorescein if a serous detachment is present (See Figure 5a, b & c).19 CNV demonstrates late phase fluorescein leakage. OCT will show subretinal fluid or retinal thickening overlying the active lesion or overlying choroidal neovascularization (See Figure 6).

The differential diagnosis for punctate inner choroidopathy is the same as for MCP syndrome. Despite the similarity to multifocal choroiditis, punctate inner choroidopathy typically does not require treatment with corticosteroids except when acute subfoveal choroiditis results in serous retinal detachment of the fovea. Choroidal neovascularization may be treated with laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy or intravitreal anti-VEGF agents.19,20 PIC tends to have a waxing and waning course with multiple recurrences.19

The visual prognosis of patients with PIC is guarded. Since subfoveal choroidal neovascularization can result in severe vision loss, CNV is a main determinate of visual outcome in these cases. Recurrences are common.19

RPC

Relentless placoid chorioretinitis is a rare, bilateral ocular inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. It typically affects patients in the second to sixth decade of life.21

This disease may be associated with decreased vision, paracentral scotoma, photopsias or floaters. The patients may have varying degrees of anterior segment inflammation and can also have a hypopyon. There may be variable amounts of vitritis present.

Active retinal lesions appear to be placoid, white to yellow and similar in appearance to those of APMPPE or serpiginous choroiditis, but these lesions tend to occur in multiples and are one disc diameter or less in size; they affect the mid and far periphery prior to involvement of the posterior pole, unlike APMPPE or serpiginous choroidopathy, which primarily and initially involve the posterior pole (See Figure 7a). The RPC lesions heal over weeks but result in chorioretinal atrophy.

All patients develop increase in size of the original lesions and develop new lesions in the periphery as well. Fifty or more lesions may be found throughout the fundus (See Figure 7b). These lesions can eventually involve the macula and can result in vision loss, metamorphopsia or scotoma. However, when the lesions heal, visual acuity is preserved even if the macula is involved.

Fluorescein angiogram demonstrates early hypofluorescence and late hyperfluorescence of these lesions and the diagnosis is based on the clinical appearance. Laboratory evaluation is typically not helpful.

Differential diagnoses can include: APMPEE, serpiginous choroiditis, multifocal choroiditis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy, persistent placoid maculopathy, viral retinitis, inflammatory choroidal vasculitis (e.g., lupus, polyarteritis nodosa), Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, neoplastic infiltration of the choroid, syphilitic chorioretinitis, sarcoid panuveitis and tuberculous choroiditis.

Patients with RPC may be treated with corticosteroids and recurrence of disease may develop despite the use of systemic corticosteroids. Although more than 50 lesions may develop in patients with this condition, long-term prognosis for this condition appears to be good. Central vision is typically preserved as a rule in these patients.21

Other Inflammatory Chorioretinopathies

The epidemiologic, clinical and angiographic features of other less common inflammatory chorioretinopathies are summarized in Table 1 (http:// www.revophth.com/email/ 0609_table/0609_ret_ table.pdf). These include acute macular neuroretinopathy, acute retinal pigment epitheliitis, unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy, acute zonal occult outer retinopathy, unifocal helioid choroiditis and persistent placoid maculopathy.

Dr. Moorthy is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology and director of the Uveitis Service at

1. Shah KH,

2. Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;89:31-45.

3. Nussenblatt RB, Mittal KK, Ryan SJ, et al. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy associated with HLA-A29 antigen and immune responsiveness to retinal S-antigen. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:147-58.

4. Gass JDM. Vitiliginous chorioretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1981;99:1778-87.

5. Sorbin L, Lam BL, Liu M, Feuer WJ,

6. Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Peters GB, Hair D, Dunn JP, Kempen JH. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy: Ocular complications and visual impairment. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:45-51.

7. Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB, Parver LM, Knox DL. Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1984;68:667-73.

8. Cantrill HL, Folk JC. Multifocal choroiditis associated with progressive subretinal fibrosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1986;101:170-80.

9. Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC, et al. Histopathology of the subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology 1985;92:838-44.

10. Dreyer RF, Gass DJ. Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. A syndrome that mimics ocular histoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1776-84.

11. Morgan CM, Schatz H. Recurrent multifocal choroiditis. Ophthalmology 1986;93:1138-47.

12. Callanan D, Gass JD. Multifocal choroiditis and choroidal neovascularization associated with the multiple evanescent white dot and acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement syndrome. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1678-85.

13. Khorram KD, Jampol LM,

14. Spaide RF, Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB. Linear streaks in multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. Retina 1991;11:229-31.

15. Parnell JR, Jampol LM, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Differentiation between presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome and multifocal choroiditis with panuveitis based on morphology of photographed fundus lesions and fluorescein angiography. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:208-12.

16. Tiedeman JS. Epstein-Barr viral antibodies in multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;103:659-63.

17. Spaide RF, Sugin S, Yannuzzi LA, De Rosa JT. Epstein-Barr virus antibodies in multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:410-13.

18. Chang LK, Spaide RF, Brue C, Freund KB, Klancnik Jr. JM, Slatker JS. Bevacizumab treatment for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization from causes other than age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:941-945.

19. Watzke RC, Packer AJ, Folk JC, et al. Punctate inner choroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1984;98:572-84.

20. Chan WM, Lai TY, Liu DT, Lam DS. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for choroidal neovascularization secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy, secondary to punctate inner choroidopathy, or of idiopathic origin. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:977-983.

21. Jones BE, Jampol LM, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Relentless placoid chorioretinitis: A new entity or an unusual variant of serpiginous chorioretinitis? Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:931-8.

22. Krill AE, Deutman AF. Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1972;74:193-205.

23. Bos PJM, Deutman AF. Acute macular neuroretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1975;80:573-84.

24. Yannuzzi LA, Jampol LM, Rabb MF, et al. Unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:1411-16.

25. Gass JDM. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. J Clin Neuro Ophthalmol 1993;13:79-97.

26. Gass JD, Agarwal A, Scott IU. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy: A long-term follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;134:329-39.

27. Hong PH, Jampol LM, Dodwel DG, et al. Unifocal helioid choroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1007-13.

28. Shields JA, Shields CL, Demirci H, Hanovar S. Solitary idiopathic choroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120:311-19.

29. Golchet PR Jampol LM, Wilson D, et al. Persistent placoid maculopathy: A new clinical entity. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2006;104:108-120.