Here, to help you make the best of these changing circumstances, four surgeons and a practice management expert share their insights on the ways in which these changing demographics will impact disease prevalence; patient flow; the delegation of tasks; individual patient management; and the profession as a whole. They also offer suggestions for actions you may want to take, based on which part of your career you are in today—early, middle or late.

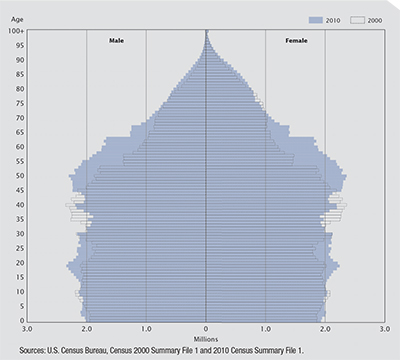

| Population by Age and Sex: 2000 and 2010 |

|

| The baby boomer generation (loosely represented by the bulge around age 40 in the 2000 census data and age 50 in the 2010 census data) continues to move toward the elder age bracket. Combined with gradually lengthening life expectancy, this foreshadows a dramatic increase in patients with age-related eye diseases over the next 10 to 30 years. |

“There are 78 million baby boomers in the United States, and every day 10,000 of them are turning 65 and becoming eligible for Medicare,” notes Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, founder and attending surgeon at Minnesota Eye Consultants and adjunct professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota Department of Ophthalmology. “For at least the next 30 years—as far ahead as most of us care about—we’re going to see increasing numbers of patients age 65 and older. This is a critical issue for providers, but also for our government because it pays for their care, and the individual over age 65 consumes 10 times as much eye care as an individual under 65. Furthermore, this change isn’t just happening in the United States; it’s also happening in Europe and China and Japan. This is going to impact ophthalmology significantly.”

John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, notes that this change will have impacts far beyond ophthalmology. “The oncoming wave of aging patients is affecting all of medicine and all geriatric and peri-geriatric service and product providers,” he says. “It’s impacting everything from adult diapers to adult care facilities, and everything in between. This is not a new phenomenon—we’ve been exposed to it for 10 or 15 years now, since the earliest baby boomers starting hitting their majority. However, we’re nowhere near the peak impact. People typically get cataract surgery in their early 70s, for example, and it will be another 10 or 15 years before the largest number of baby boomers reach that age.”

Dr. Lindstrom notes that the issues accompanying this change will be exacerbated by another shift. “As the elderly population grows, there will be about 450 new ophthalmology residents graduating every year,” he says. “At the same time, if you assume most of us have about a 35-year career, about 550 older ophthalmologists will be retiring each year. That means the number of ophthalmic providers will be declining by about 100 per year—and that calculation doesn’t take into account that the current pool of ophthalmologists is top-heavy, meaning that more of us are over the age of 45 than under the age of 45. Today there’s a small increase in the number of residency slots every year, but that’s not going to have a meaningful impact in terms of the upcoming demographic shift.”

Mr. Pinto agrees, noting that while the overall population of America is growing about 1 percent a year, the senior population is growing at about 3 percent a year. “Because seniors require about 10 times as much eye care as younger patients, we’ve got a 4 or 5 percent annual increase in the demand for ophthalmic care in America,” he says. “Meanwhile, the growth rate in the number of ophthalmologists right now is somewhere between flat and 1 percent. This is already causing some serious labor shortages, particularly in secondary markets, leading to a sharp uptick in the number of practices that either can’t find a successor doctor or are having to bid salary prices way up. For example, a decade ago a general ophthalmologist might have expected a base salary of $150,000 to $175,000. Those numbers are now in the mid $200,000s and up, and they can be even higher in secondary, rural, Midwestern markets.”

Demographics and Disease

One aspect of this shift that will clearly impact ophthalmologists is a greater need for treatment of diseases most commonly seen in the elderly. Dr. Lindstrom says both practitioners and companies are going to want to be on top of these conditions. “The number-one medical problem is cataract,” he notes. “We’re doing about 4 million cataract surgeries a year in the United States today, about 11 people per thousand, and that rate is growing at 3.5 percent per year. So, currently about 9,000 cataract surgeons are treating about 4 million cataracts per year. I project that in 20 years—about the middle of the career for residents graduating today—about 8,000 cataract surgeons will be treating 8 million cataracts per year. Those doctors are going to have to be even more efficient than we are today, and the federal government’s triple aim of quality care, happy patients and reduced cost is going to pressure them to find some way to manage that.

“The other age-related diseases that will become increasingly important are glaucoma, ocular surface diseases such as dry eye and blepharitis, and what may be the largest group, age-related diseases of the retina,” he continues. “That’s because diabetes is exploding, along with an epidemic of obesity, leading to an enormous amount of diabetic retinopathy, as well as increases in dry and wet macular degeneration. These are currently quite expensive to treat, since intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF drugs have become the favorite treatment for just about all of these retinal problems.”

| The Aging Optic Nerve |

| When managing elderly patients, it’s important to be able to differentiate between disease-related changes and changes that occur naturally with aging. Thasarat S. Vajaranant, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago and director of the Glaucoma Service at the Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary, offers some insights into the differences. “The optic nerve undergoes an aging process that results in a decreased number of retinal ganglion cells and nerve fibers,” she explains. “Those changes subsequently lead to reduced visual sensitivity. Imaging with optical coherence tomography typically shows decreasing thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer and macula with age, and visual field testing shows a corresponding decline.1,2 Therefore, in clinical practice it’s important to use age-appropriate normative data when evaluating optic nerve imaging and visual field testing results. In addition, increased cupping has been documented as a normal part of optic nerve aging. Interestingly, a previous study conducted by [Jovina L. See, MD] and colleagues3 using the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph demonstrated that, similar to glaucoma, age-related cupping occurs preferentially in the inferotemporal region.” Dr. Vajaranant points out that changes occurring in primary open-angle glaucoma age-related optic neuropathy are similar to those observed in normal optic nerve aging. “Compared to a disease process like glaucoma, changes occur at a much slower rate in normal aging of the optic nerve,” she says. “In fact, primary open-angle glaucoma is thought to represent accelerated aging of the optic nerve.4 Practically speaking, it should take a decade for the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber to decrease by 2 to 4 µm. So if the optic nerve is losing its fibers faster than that—taking into account the variability of the imaging technology you’re employing—the change is likely due to a disease process rather than normal aging.” Dr. Vajaranant adds that the effects of normal aging generally do not occur suddenly. “Visual sensitivity and contrast sensitivity do decrease over time, but normal aging is a slow process, so patients usually adapt,” she says. “Patients should not interpret acute visual symptoms as being part of normal aging.” Asked what advice doctors can offer patients to help slow the aging of the visual system, Dr. Vajaranant says the best advice is to maintain good general and vascular health. “The aging process involves oxidative stress, so a diet rich in antioxidants should be beneficial, at least in theory,” she notes. “For example, [Anne L. Coleman, MD, PhD] and colleagues showed that foods rich in antioxidants are protective against primary open-angle glaucoma.5 However, at present there is no evidence that a high-dose antioxidant supplement will have a beneficial effect on the health of the optic nerve.” —CK 1. Vajaranant TS, Pasquale LR. Estrogen deficiency accelerates aging of the optic nerve. Menopause 2012;19:8:942-947. 2. Dolman CL, McCormick AQ, Drance SM. Aging of the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:11:2053-2058. 3. See JL, Nicolela MT, Chauhan BC. Rates of neuroretinal rim and peripapillary atrophy area change: A comparative study of glaucoma patients and normal controls. Ophthalmology 2009;116:5:840-847. 4. Guedes G, Tsai JC, Loewen NA. Glaucoma and aging. Curr Aging Sci 2011;4:2:110-117. 5. Coleman AL, Stone KL, Kodjebacheva G, et al. Glaucoma risk and the consumption of fruits and vegetables among older women in the study of osteoporotic fractures. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;145:6:1081-1089. |

“In terms of retinal disease, we’ll need to get some of the extended-release options working; having an injection every month is just not feasible in the long run,” he says. “It’s too expensive and too hard on the families of the patients. We’re going to have to get to the point where retinal disease is treated more like glaucoma, where the patient is seen twice a year and gets some form of extended-release medication. That will be more manageable. Otherwise, we won’t have enough ophthalmologists to take care of the retinal diseases.”

Dr. Lindstrom points out that it will pay to be adept at treating these diseases. “If you know which problems are going to be widespread and you want to be busy, then you should be good at treating those things,” he says. “If I were a retina guy, I’d stay on top of the latest treatments for diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration. If I were a general ophthalmologist, I’d master the latest treatments for cataract, glaucoma and ocular surface disease.

If I were a refractive surgeon, I’d be learning to implement the newest surgical alternatives for treating presbyopia. And if I were a company, I’d invest in finding new treatments for those diseases.”

Changes in the Office

The coming gradual shift in medical focus will be accompanied by some very practical issues in the office and clinic. Perry S. Binder, MS, MD, clinical professor in the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine, notes that serving a much larger contingent of elderly people in a practice will necessitate changes in several areas. “Patient education may have to be adjusted to account for the fact that elderly patients may not see as well, hear as well or think as clearly as younger patients,” he says. “They may have difficulty with some of our written or audiovisual educational materials. Those materials will have to be redesigned with elderly patients in mind.

“Then there’s the issue of communicating with elderly patients when they’re outside the office,” he continues. “Scripts for phone calls may have to be redesigned with this in mind. And by what means do you communicate with elderly patients when they’re outside the office? Robocalls? Sending videos by mail or computer?

“Another reality is that an increase in the number of elderly patients may cause a major change in patient flow,” he notes. “Testing will take longer. The ergonomics of your equipment may need to shift, and your staff may need to be trained to work better with older patients. And of course, there are the financial concerns; the time it takes to see these patients will increase while the reimbursement for seeing them will almost certainly decrease. Who’s going to pay their bills? Which procedures will and won’t be covered? Will some doctors stop seeing elderly patients because of low reimbursements? I don’t know how we’re going to come to grips with all of this.”

Mr. Pinto notes that with the swelling number of elderly patients and decreasing reimbursements, more ophthalmologists might think about trying to decouple from Medicare and open a cash-and-carry practice that doesn’t accept insurance. “In reality, this won’t be practical for the vast majority of ophthalmologists,” he says. “There are a few very elite ophthalmologists in selected markets who have dropped out of Medicare and are working on a pure cash-and-carry basis, but they are the exception. Sixty percent of the cash flow in ophthalmology comes from patients over 65 who are Medicare beneficiaries, so dropping out of Medicare isn’t very practical.

“To put this in context,” he continues, “there are about 15,000 active practicing ophthalmologists in America. I’d be surprised if more than 150—1 percent—are making a living by directly charging the patient for geriatric services such as cataract care. That number might increase a little in the future, as there are more and more patients and fewer doctors, but you’re not going to see a third of ophthalmologists dropping out of Medicare.”

Calling in the Cavalry

One of the inescapable realities of managing an ever-increasing number of patients will be the need to delegate many tasks to others in a practice. “Ophthalmologists 20 years from now will be very busy if they want to be,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “To manage the upcoming patient numbers they’ll have to become even more efficient. That will mean lots of jobs for ophthalmic technicians and lots of opportunities for optometrists and maybe physicians’ assistants. Ophthalmologists are going to be a scarce resource, and I think that will be a good thing for the field.”

Dr. Binder believes that relying more on your staff is likely to become a necessity. “Dental hygienists do a lot of what the dentist used to do,” he notes. “I now see a nurse practitioner for most of my routine dermatology needs—often I don’t even see the dermatologist. So I think we’re going to see a lot more non-medical personnel taking over the basic, mundane clinical tasks such as vision-testing, refraction, topography measurements, fundus photography and so forth, to allow us to handle more patients per unit time with efficiency. In fact, I think this is already starting to happen. Many doctors are making changes in their offices to improve efficiency through better education of patients and staff, and by modifying patient flow and delegating testing to non-doctors.”

Carla J. Siegfried, MD, the Jacquelyn E. and Allan E. Kolker, MD Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, agrees. “We’ll have to devise team strategies to provide better care for patients,” she says. “I’ve heard creative suggestions such as having a relatively healthy patient see a physician extender instead of the ophthalmologist once every so many visits. That could cut the physician’s load by 25 percent. We’ll definitely need to continue to think of new methods to manage this.”

This is likely to mean that more practices will be adding optometrists to their staff—a trend that’s already evident. “Our ability to provide eye care for every senior is already hitting a wall,” says Mr. Pinto. “Practices are responding by adding extenders such as optometrists. I believe that a decade or so from now the typical ophthalmology practice will have one to three optometrists for every ophthalmologist.”

This was not the case in the past. “When I started in practice, only about 1 percent of ophthalmologists employed an optometrist,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “Now about 50 percent do. In the future I think every practice will have to be integrated with both MDs and ODs. And because most surgery will be done in an ASC or office, doctors will be looking for ways to participate on the facility side, so to speak, in order to be efficient enough.”

Dr. Binder points out that today’s optometrists are facing many of the same issues. “They’re going to have to handle larger numbers of patients who are living longer with more visual disorders,” he says. “I think it’s likely that most optometrists will be working with ophthalmologists in order to manage this new reality.”

| The Lifespan Factor |

| Carla J. Siegfried, MD, the Jacquelyn E. and Allan E. Kolker, MD Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, points out another issue that will become more prominent as the patient population in ophthalmologists’ offices continues to age: judging how long the patient you’re treating may live. It’s not uncommon for people to assume that a person in her 90s, for example, may not live many more years, but that assumption could be totally mistaken—especially in the upcoming years, as lifespans will likely increase. “Age-adjusted life expectancy is the subject of a great deal of scientific research,” Dr. Siegfried notes. “Meanwhile, many of our treatment algorithms are guided by our ideas about the patient’s potential lifespan. This can result in patients being either overtreated or undertreated, both of which can be detrimental to their long-term care. “For example, I saw a 93-year-old glaucoma patient yesterday,” she says. “We had decided we would take a small, non-invasive step and just do a laser procedure to try to control her pressure. But I told her that her disease was so far advanced that I wouldn’t completely rule out further, more aggressive treatment to enhance long-term preservation of vision because there was a very good chance she could live another 10 years. She and her daughter looked at me, and then they said, ‘You know, you might be right.’ “These are the kinds of important questions we deal with every day,” Dr. Siegfried continues. “It’s interesting that the health- and life-insurance industries devote a great deal of attention to actuarial science—determining how long people are likely to live—but we don’t routinely analyze this information to provide age-appropriate care. We need to improve this aspect of our patient management. “Of course, we don’t want to suggest invasive, risky treatments for patients with a short life expectancy,” she adds. “But shouldn’t we provide appropriate care for those who do have a high quality of life, even if they’re over 80, 90 or even 100 years of age? These are challenging questions as we look at the cost of providing this care, but we must also examine the cost of rehabilitation and long-term care. If someone has multiple falls because of poor vision due to withholding appropriate treatment, and ultimately requires skilled nursing care, that’s a huge cost to society.” —CK |

Clearly this demographic shift will affect all ophthalmologists who treat seniors, but it’s equally clear that the impact will be quite different depending on where you happen to be in your career. “You can think of an ophthalmologist’s career as having three stages: the first years, the middle years and the final 10 years,” says Mr. Pinto. “For the next several years, if you’re in the first third of your career you’ll find more jobs available at higher salaries and more patients to take care of—perhaps even more than you’re comfortable dealing with. And if you’re an ambitious doctor you’ll have as much opportunity to provide surgical care as you’d like. This means you’ll be able to climb up the learning and experience and skills curve faster than the previous generation, and you’ll be more likely to find a satisfactory professional setting.”

“My advice to young doctors who are just starting out and choosing a specialty,” says Dr. Binder, “would be to understand how the field is going to change, what kind of patients you’re going to treat in a given subspecialty and how many elderly patients you’re going to see, keeping in mind that reimbursements will go down significantly over the next five to 10 years. You’ll have to figure out what subspecialty within ophthalmology will make you happiest. Then I would suggest that you spend time with doctors in that subspecialty to see how they’re handling these large volumes of people, such as the repeat cases that need intravitreal injections for macular degeneration and diabetics who need regular retinal treatments and follow-up exams and fluorescein angiograms. Glaucoma specialists also will be dealing with many repeat visits from elderly patients.

“Once you decide that a specialty will work for you, you need to consider whether you want to start your own practice or join a group that can handle this huge number of patients more efficiently,” he continues. “I believe we’re going to see more of that. I think the private practitioner is largely going to disappear, except for the carriage-trade ophthalmologists—and I think the carriage trade is going to be a very small segment of ophthalmology.”

What about career options such as research and academia? Mr. Pinto believes the surplus of job openings may lead fewer young ophthalmologists to choose those options. “There will be plenty of patients to take care of,” he says.

“Young ophthalmologists won’t feel the need to seek out an alternate career. Anybody who wants to be a busy geriatric ophthalmologist today, assuming he’s in a decent market, is going to be as busy as he wants to be.”

Middle to Late Career

Mr. Pinto notes that the impact of the demographic shift on ophthalmologists in the middle or later parts of their careers will be somewhat different. “If you’re in the middle third of your career, roughly in your 40s and early 50s, you need to stay ahead of the curve and anticipate the need to bring on additional ophthalmologists,” he says. “Anticipating this before the need becomes dire is important because the replacement cycle time isn’t six or nine months the way it used to be. Depending on where you work and live, it may take a year or two—maybe even three years—to find the next ophthalmologist to join your practice. You should also be prepared to pay more to hire a partner-track associate. The good news is that you’re going to have an increasing amount of work for the new doctor to do so you won’t have to carry him as long, and the higher base salary should be affordable.

“If you’re in the final third of your career and you’re starting to think about succession planning, the watchword is to plan as far in advance as you can, because it’s getting harder to find new owner-track associates to come in and take over a practice,” he continues. “There are fewer doctors and more openings, so an increasing number of doctors who are looking for a succession plan are turning to their nearby friendly competitors for a buyout rather than going the old route of bringing in a young doctor and grooming him or her for a takeover.

“Also, when you’re doing your personal financial planning, don’t assume that you’ll get anything more than salvage value for your equipment, or much credit for the residual value of your accounts receivable and working bank accounts. You should also expect to have little or no good-will value. Of course, this won’t be true in every case, but the point is that when you’re planning your retirement and making assumptions about your retirement funding, don’t be too optimistic about what you’re going to be able to extract from your practice.

“Understanding the nature of this shift is also very important if you own the building you practice in, because it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find young doctors who are willing to come aboard, buy your practice and also take the risk of paying a hefty price for the real estate,” he says. “Fortunately, your building’s value will be based on the local real estate market as much as anything else, because most medical buildings can be repurposed and taken over by an accounting firm or law firm or architectural firm. Either way, it all comes down to the need for advance planning and greater effort when it’s time to start pulling the trigger on these things.”

Tips for Managing Seniors

In addition to an increase in the prevalence of certain diseases seen in many practices, the growing number of elderly patients will necessitate some changes in the way doctors interact with patients. Dr. Siegfried lists some things to keep in mind:

• The new crop of senior citizens will have different expectations. “They certainly will expect to remain active—even more so than current elderly patients,” she says. “They won’t just want to play golf, they’ll want to continue driving a car and having high-quality lives.”

• Patient perception of age may be an issue. “I’ve seen people make poor decisions in the management of their disease, against our advice, simply because they have false preconceptions about being old,” says Dr. Siegfried. “They may assume that their illness is a normal part of aging, for example, and therefore should be suffered rather than treated. We need to be certain that patients understand that age and illness do not necessarily go hand in hand.”

• Low-vision aids will become even more important. “With elderly patients becoming an increasingly large part of our patient population, helping patients do more with what they have will need to become a major part of the services a practice offers,” she says. “Thanks to readily available devices like computers and tablets allowing people to alter font size and contrast, technology should play a big part in this.”

• We may have to rely less on functional testing. “Very elderly patients often have a shorter attention span, slower reaction times and more difficulty concentrating,” notes Dr. Siegfried. “Until better visual-function tests come along, we may have to rely less on these tests with our oldest patients.”

• Side effects of your prescriptions may have greater impact on a very elderly person. “Some of the medications we prescribe can have a profound effect on systemic circulation, blood pressure and mental status,” notes Dr. Siegfried. “Some eye drops can affect a patient’s level of energy significantly, leading to a greater risk of falling. This can certainly affect the patient’s quality of life and ability to get out and interact with others.

“Medications like beta blockers, for example, can cause fatigue and dizziness and alter blood pressure,” she continues. “I saw an 82-year-old patient yesterday who would take his drops and then would have to go and take a nap because he got so tired. His energy and activity dropped significantly, and he’d never had this problem until he began using the drops. I told him to stop the drops. These issues will become increasingly important with the aging of our patient population.”

• Interaction with the patient’s primary-care physician will be much more important. Dr. Siegfried notes that the kind of problem discussed above necessitates good communication between physicians. “We’ll have to be increasingly vigilant about making sure the primary-care doctor knows about the systemic side effects of the topical medications that the patient is using, and vice versa—we’ll need to be aware of the effects of any systemic drugs the patient is taking.”

• The choice between medication and surgery involves different factors in the very elderly. “It’s legitimate to have concerns about performing surgery on a very elderly patient,” says Dr. Siegfried. “The tissues are more fragile and anesthesia risks can be more serious. On the other hand, medications come with their own potential problems; they have side effects, and the patient may have more difficulty using drops properly due to memory problems, arthritis and difficulty keeping track of multiple medications. There is no simple answer regarding what’s best. You must consider each individual and determine where the greatest benefit and lowest risk lie.”

Dr. Siegfried points out that if you do take a very elderly patient to surgery, you want to make sure you get the most out of it. “Some of the newer procedures sound very promising in terms of their safety profile, but they may have a lower likelihood of long-term success,” she says. “With a younger patient, a lower-risk procedure may be appropriate because you can always bring the patient back into the OR; but with an elderly patient the bigger risk may be taking the patient to the OR again. So, you want to be sure you do what you need to do while you’re there the first time.”

• Be on the lookout for existing consequences of previous years of medication use (such as drops). “Preservatives may have altered the tissue, causing chronic inflammation and irritation,” notes Dr. Siegfried. “That can definitely cause issues with wound healing and scar tissue. It’s important to be prepared for this and potentially pretreat with anti-inflammatory medications.”

• Be aware of the issue of dual sensory impairment. Dr. Siegfried points out that many elderly patients already have lost all or part of another sense such as hearing. “It’s been shown that impairment of two senses can have an exponential effect on your functionality,” she says. “Many of our elderly patients are hearing-impaired. If they start to lose their vision, the problems they are having may increase dramatically, as they are more likely to withdraw from the world.”

Dr. Siegfried says this makes it important to urge family members to address other sensory problems that are not vision-related. “Sometimes I have to virtually yell at a patient in the office because he can’t hear me,” she says. “I’ll turn to the family member and say, ‘Have you thought about getting your grandfather a hearing aid?’ The family member will say, ‘Oh no, he doesn’t want to do that.’ I explain that he really does need to do that. Sometimes hearing it from a doctor will get them to take action. In fact, some practices have an audiologist on staff. Having this service available may become increasingly important as your patient population gets older.”

Dr. Siegfried says this concern extends to non-auditory problems as well. “If the patient is stumbling, you might suggest getting a walking aid,” she says. “A lot of people are very resistant to using a hearing aid or walker, but you may discover the patient has fallen three times in the past month. The family may say the patient is stubborn, but when she breaks her hip, she could require surgery and/or extensive rehabilitation, or perhaps be confined to a wheelchair. So you may have to strongly encourage the patient and family to take the needed steps.

“Vision loss is also more serious if a patient already has some level of dementia,” she adds. “Losing vision can make people become more isolated socially, affecting how they interact and how engaged they are, causing the dementia to worsen. At the same time, I’ve seen a relative reversal of some aspects of dementia when we provide better vision because the individual can interact more easily with the world around him.”

• Develop a standard protocol for involving the family when elderly patients need assistance. “Having the family involved is critical, especially when you’re making decisions about taking the patient to surgery,” says Dr. Siegfried. “Family members can help to reinforce not only what the patient needs to do after surgery, but help the patient prepare for it mentally.

“In general, family members need to understand as much as they can about why we’re doing what we’re doing,” she adds. “For example, in our practice we have charts that we give to both the patient and family members with written information about the patient’s daily medications and the time they should be instilled. This includes a form that shows the color of the cap of each medication bottle.”

• Older patients sometimes are more reluctant to ask for help when a problem occurs. Take preemptive action to avoid this. “This is partly an education issue,” notes Dr. Siegfried. “Let elderly patients know it’s important to contact you if they need help, and that someone is available 24/7 to answer their questions or to see them. Then, make it easy for them to call. This will be especially critical for any ophthalmologist who performs surgery.”

The Future, for Better or Worse

Given the multitude of changes coming down the pike, some ophthalmologists are optimistic; others, not so much. Dr. Binder is concerned about how medicine is going to be delivered in the next five to 10 years and beyond. “I know there are some ophthalmologists who believe this population shift will be a fabulous opportunity, with so many people needing cataract surgery,” he says. “But on the other hand, who’s going to pay for it? How are we going to deliver the best care for these patients? Yes, we’ll have new technologies, new medications, stem cells and a better understanding of genetics to help prevent a lot of the disease that we see today. There’s no question that people will live longer and have better-quality lives because of those advances. But where will the money for ongoing R&D come from? Those sources are drying up. Meanwhile, it’s very frustrating to not be able to prescribe Restasis, for example, when its probably the best treatment for a given patient, just because we can’t get reimbursed for it.”

Dr. Binder notes that the current environment is also making American surgeons the last to have access to new technologies and medical treatments. “Companies are moving overseas to get away from our tax structure,” he says.

“As a result, Americans are getting further and further behind the technology curve. In the past I was able to personally introduce new technologies to doctors in Japan and France and South America. Now, that’s totally reversed—companies are releasing products outside the United States first. We’re not getting these technologies until three to five years after the Europeans and South Americans get them. Our health care is suffering as a result, and this may not bode well in terms of managing the coming demographic shift.”

Dr. Lindstrom’s view is somewhat more optimistic. He notes that things have changed dramatically since he first went into practice, and those changes are likely to continue. “I’m coming to the end of my practice years,” he says.

“But consider what we were doing when I started. We had to hospitalize a patient for cataract surgery, which was invasive surgery, one procedure per hour. Patients spent four days in the hospital and then were fitted with a contact lens or aphakic spectacles. Today, this is outpatient surgery, 90 percent of which is done at an ambulatory surgery center. Now we do two to three cases per hour, on average, and if you look at inflation-adjusted fees, we’re doing it for about 10 percent of what it cost 40 years ago.

“Looking ahead, it seems clear that things are going to continue to move in that direction,” he says. “We’ll probably transition from ASCs to office surgery centers; most of the surgeries will be done in, or adjacent to, a doctor’s office. We’ll be doing bilateral, same-day sequential cataract surgery. Instead of drops, doctors will use an injection or implant to prevent infection and inflammation. There will be fewer postoperative visits to the office, and I think many of the postoperative visits that do take place will be virtual. We’ll have apps that can check your vision, refraction and visual field, take an external eye photo and fundus photo, and maybe even do optical coherence tomography. Basically, our patients will sit at home and do their own vision and refraction.

“Our ability to generate good outcomes with cataract surgery will continue to grow, and that will lead to patients having their surgery at younger and younger ages,” he continues. “As the government gradually increases the age of eligibility for Medicare, those two factors will eventually lead to cataract surgery being done below the Medicare age. That will relieve the government of a large financial burden (and help to get the government out of our hair). Meanwhile, I believe the fee-for-service model that we know today will gradually disappear. There will be some form of population management; we’ll be given a group of patients to take care of who are prepaid for basic eye care. At the same time, patients will have to share more of the responsibility for their eye care, leading to more of the patient-pay model. I think patients will be able to choose premium options and the like more easily than they can today. That will be a plus.

“I think the changes we’re seeing today will accelerate,” he concludes. “Those of us who started 30 or 40 years ago couldn’t have imagined the things we’re doing today, and those who are starting today can’t imagine what they’ll be doing in 20 years. But whatever happens, we’ll have to provide very high-quality care and outcomes because we’re going to continue to have very demanding patients, and they’re going to be evaluating us. We’ll need to ensure that they go away satisfied and, in general, the cost of intervention will have to go down. But we’ve managed this amazingly well over the past 30 or 40 years. We’re much more efficient than we were; we have better outcomes and happier patients than we did back then. It’s true that many of today’s treatments don’t generate as good an outcome as they should, and some are not cost-efficient. But they will become better in the future.” REVIEW