The differential diagnosis in this patient with a corneal ulcer and a history of contact lens use included infectious keratitis of bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic etiology. In this case, given her refractory symptoms, the presence of radial keratoneuritis, and pain out of proportion to exam findings, there was high suspicion for Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Corneal scraping was performed and showed the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts. Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. She

|

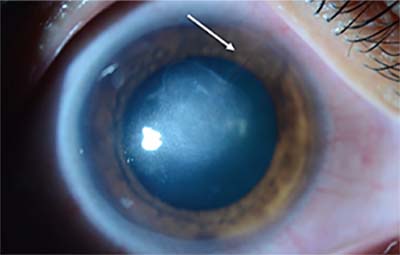

| Figure 2. Anterior segment photograph of the right eye at eight weeks follow-up. There is resolution of the epithelial defect with less dense infiltrate and resolved radial keratitis. Superonasal neovascularization can be seen extending to the central cornea (arrow). |

After 10 days of treatment, the patient reported moderate improvement in her pain. Her vision was unchanged. Mild clinical improvement was noted, with improving epithelial defect and less dense infiltrate and radial keratoneuritis. After a long discussion with the patient, a novel, off-label therapy, oral miltefosine 50 mg every eight hours, was added to her regimen. After the addition of miltefosine, she demonstrated more rapid improvement in her clinical course (See Figure 2).

Discussion

Acanthamoeba is a ubiquitous, free-living protozoan found predominantly in soil and freshwater sources. First reported in 1973,1 Acanthamoeba keratitis has been strongly associated with soft contact lens wear and contaminated water exposure. Infection can cause severe pain with sight-threatening sequelae. Data from 13 ophthalmologic institutions in the United States revealed that the annual incidence of AK markedly increased from 22 cases in 1999 to 170 cases in 2007.2

In early stages of AK, pseudodendritic or punctate corneal epithelial lesions, dot subepithelial infiltration or recurrent epithelial erosion can be seen.3 The pseudodendritic appearance of the epithelial change causes frequent misdiagnosis as herpes simplex keratitis.4 In a series of 59 patients with AK, 10 (17 percent) had radial keratoneuritis on presentation. Of the patients with stromal involvement, 32 percent had a ring infiltrate, 5 percent had a hypopyon, and 2 percent had keratic precipitates.5 In more advanced stages, deep stromal ulcers may be present and exhibit pale or yellow-white purulent infiltration with a necrotic surface. In even later stages, corneal ulcers may develop thinning and perforation.3

AK is one of the most challenging ocular infections to manage. The disease stage at initial presentation is strongly associated with treatment outcome.4 Current first-line treatment for AK involves topical therapy with biguanides (PHMB or chlorhexidine). Topical propamidine isethionate is also commonly used as a first- or second-line agent. A study of patients with AK treated at a tertiary-care eye hospital found that 53 percent required therapeutic grafts.6 Unfortunately, the prognosis of penetrating keratoplasty for active AK remains poor.7 Thus, it’s necessary to enhance the rate of early detection and identify new, more effective anti-amoebic therapies to improve outcomes.

Miltefosine, an oral alkylphosphocholine drug, has shown early promise in the treatment of Acanthamoeba infections. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of visceral leishmanaisis, miltefosine is an antiprotozoal agent with in vitro activity against free-living amoebae, including Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Acanthamoeba species. As of 2013, miltefosine has been available in the United States directly from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under an expanded-access investigational new drug protocol for use in the treatment of free-living amoeba infections.8 There are currently five cases in the literature documenting the use of miltefosine in the treatment of systemic or disseminated Acanthamoeba infection.9 Miltefosine has shown activity against AK in hamster and rat models.10,11 To our knowledge, there are no reported cases documenting the use of miltefosine in the treatment of AK. In our patient, the addition of miltefosine 50 mg orally every eight hours for one month to the existing regimen of topical PHMB and propamidine isethionate appeared to result in a more rapid resolution of keratitis with respect to infiltrate size, density and clinical symptoms than expected for similar cases.

In summary, AK is a severe, sight-threatening infection that’s often difficult to manage. This ubiquitous organism should be considered as a cause of keratitis in patients who don’t respond to initial antibiotics, especially those with a history of soft contact lens use or contaminated water exposure. Clinicians must also be suspicious of AK in contact lens wearers diagnosed with HSV keratitis who aren’t responding appropriately to therapy.

In this case report, we describe a patient with AK who was successfully treated with oral miltefosine in addition to topical agents. To our knowledge, this is the first case documenting miltefosine treatment of AK. This novel agent appears to show promise in the treatment of free-living amoebic infections such as AK, although further studies are needed to elucidate its role in treating this devastating corneal infection. REVIEW

1. Jones BR, McGill JI, Steele AD. Recurrent suppurative kerato-uveitis with loss of eye due to infection by Acanthamoeba castellani. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1975;95:210-3.

2. Yoder JS, Verani J, Heidman N, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: the persistence of cases following a multistate outbreak. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2012;19:221-5.

3. Jiang C, Sun X, Wang Z, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: clinical characteristics and management. Ocul Surf 2015;13:2:164-8.

4. Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2006;17:327-31.

5. Chew HF, Yildiz EH, Hammersmith KM, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors associated with Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 2011;30:435–441.

6. Tanhehco T, Colby K. The clinical experience of Acanthamoeba keratitis at a tertiary care eye hospital. Cornea 2010;29:1005-10.

7. Kashiwabuchi RT, de Freitas D, Alvarenga LS, et al. Corneal graft survival after therapeutic keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol 2008;86:666-9.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Investigational drug available directly from CDC for the treatment of infections with free-living amebae. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:666.

9. Brondfield MN, Reid MJ, Rutishauser RL, et al. Disseminated Acanthamoeba infection in a heart transplant recipient treated successfully with a miltefosine-containing regimen: Case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis 2017;19:2.

10. Polat ZA, Walochnik J, Obwaller A, et al. Miltefosine and polyhexamethylene biguanide: A new drug combination for the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:2:151-8.

11. Polat ZA, Obwaller A, Vural A, et al. Efficacy of miltefosine for topical treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Syrian hamsters. Parasitol Res 2012; 110: 515–20.