Reports of bacterial and fungal organisms infiltrating the interface between the donor and host corneas have accompanied the introduction of new corneal transplantation techniques. In a multicenter study, my colleagues and I have identified four such cases, including the first such report in 2003. (John T, et al.

I initially called this "sandwich keratitis," but have since adopted the phrase "sandwich infectious keratitis," or SIK syndrome, as suggested by Carol Karp, MD. Clinicians must be on the alert for what appear to be debris in the corneal interface after varied lamellar keratoplasty techniques.

Failure to make an early diagnosis of these infectious infiltrates in the interface can have devastating results. In four cases our group is studying, two responded to medical treatment; the other two required further surgery—one a full-thickness therapeutic keratoplasty (TKP), the other a lamellar keratoplasty followed by full-thickness TKP after recurrence. (Karp C, Malbran E, Wiley L, John M, O'Brien T, Kieval J, Forster RK, Gorovoy M; unpublished data, January 2009)

The Surgical Procedures

Our collaborative study from multiple centers involves these procedures:

• deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) for psuedophakic bullous keratopathy;

• deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) for keratoconus;

• anterior lamellar keratoplasty (ALK) for lattice dystrophy; and

• Descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) for pseudophakic bullous keratopathy.

These corneal transplantation techniques have moved away from full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty to what I've called selective tissue corneal transplantation, or STCT.1 In standard transplantation, the surgeon replaces the entire cornea whether the disease process is in the front, middle or back part of the patient's cornea. With STCT, the surgeon replaces only the diseased part of cornea with similar healthy donor tissue and thus retains the healthy part of the patient's cornea that is unaffected by the disease process.

In posterior lamellar keratoplasty, the interface is in the back part of cornea; in ALK, the interface is located in the front, middle or deep part of the cornea depending on the type of ALK procedure. The response of the body's defense mechanism to an infectious process entrapped in any of these areas of the donor-recipient interface may be delayed, especially in early stages of the infection.

SIK Versus Corneal Ulcer

SIK syndrome is unlike a surface corneal ulcer. With the latter, the infection commences on the outside surface of the cornea and progresses into the corneal stroma, resulting in corneal ulceration and thinning of the cornea.

In STCT, the selective tissue removal and replacement techniques create an interface between the donor tissue and the patient's own cornea. This creates an interface in which infectious organisms can be introduced during the surgical procedure and then get trapped, much like the filling in a sandwich.

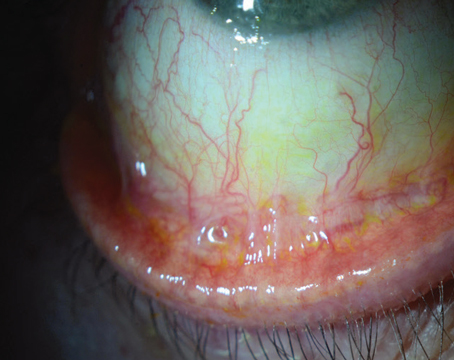

Diagnosing SIK syndrome is also quite different from diagnosing a corneal surface ulcer. Again, the latter manifests a rather obvious presentation: redness, excessive tearing, blurred vision, photophobia, pain and discomfort. The often unbearable ocular symptoms will usually provoke the patient to call your office early in the disease process to obtain medical treatment and relief from the symptoms. In contrast, the relative lack of ocular symptoms, especially in the early stages of SIK syndrome, can result in a delayed patient presentation with a more advanced stage of the infectious process.

Culturing a corneal ulcer is relatively easy; simply scrape the corneal ulcer with a Kimura spatula at the ulcer margins and plate the material on the appropriate culture plates. Even if the culture is negative or medical therapy fails, a corneal surface biopsy is simple compared to what SIK syndrome requires. Management of a surface ulcer is straightforward as well: Treat with frequent, broad-spectrum antibiotics, cycloplegia, close monitoring and changing antibiotics as needed based on clinical response and culture results.

Why SIK Is Difficult to Diagnose

With SIK syndrome the signs are more subtle. Because the infectious organisms are "trapped" between the host and donor cornea, the immune system often does not recognize the infection as readily, especially in the early stages. The corneal interface is a potential space where microorganisms, when introduced, can multiply and grow in what may be considered as a "safe haven" for these organisms.

The patient does not complain of any of the symptoms typical of ulcerative keratitis. The eye is not any redder than normal following surgery. By the time the body reacts, the infection has already spread significantly and treatment will be difficult.

Slit-lamp examination of the post-STCT eye is critical. Infectious organisms in the interface can easily be mistaken for debris or epithelial in-growth. Problematic opacities will be white, small, irregular or circular. Frequent, close follow-up is essential as these opacities can multiply, increase in size and become more confluent in one to three weeks. Any opacity in the interface should raise a high degree of suspicion for SIK syndrome. This should be the first diagnosis to rule out in your differential diagnosis following any STCT procedure.

If you do see an interface infiltrate, you need to monitor that closely. Schedule the patient for follow-up sooner than the one-week and four-week schedule after the operation. Even daily or every-other-day monitoring may be necessary in these cases. One case I treated occurred six weeks after the operation. Factors that influence the progression of the infection are the number of involved organisms, their virulence, their susceptibility to the antibiotics being used, and the use of postoperative topical corticosteroid drops.

Further complicating the diagnosis is the depth of the intracorneal infection. Obtaining a culture of microbes trapped between layers of tissue is problematic. If the donor corneal rim culture turns out positive, it may be of some help in the choice of the initial antibiotic.

In SIK syndrome, particularly after DLEK or DSAEK, getting to the interface requires penetrating the patient's cornea. This poses two risks:

• displacing the donor disk and having it fall into the anterior chamber; or

• opening the donor-recipient interface to the anterior chamber, allowing the infection to spread into the anterior chamber and subsequently even into the posterior segment of the eye. Such an iatrogenic spread of infection can convert what was initially an isolated, intracorneal infection within the corneal sandwich into an endophthalmitis with the risk of losing the eye. Hence, this approach is not recommended.

Treatment

Likewise, treatment of SIK syndrome is difficult. With a corneal ulcer, antibiotics go directly to the target site, applying the highest concentration where they are needed. With SIK syndrome, the medication has to penetrate the intact corneal epithelium, and then pass through the corneal stroma to finally reach the interface. The deeper the interface, the lower the concentration of medication that reaches it—certainly less than what it would be when you treat a direct surface corneal ulceration.

In half of our study cases, fungus was the offending organism with or without additional bacteria. We've identified the following organisms: Candida glabrata; Streptococcus pneumoniae; Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; and bacteria, fungus and virus (herpes simplex on the endothelium but not in the interface).

Although the most significant etiology our group has found is fungal, the toxicity of antifungal agents precludes their use as routine first-line therapy. I usually recommend using antifungal agents only after having made a definitive culture-positive diagnosis.

Treat SIK syndrome as you would a corneal ulcer. That is, start with frequent antibiotics, either the newer fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin 1.5% (Iquix), or fortified antibiotics, frequently around the clock. The antibiotic treatment regimen must be intensive: I usually recommend applying the topical antibiotic every 15 minutes for the first six hours; then every 30 minutes for the next 18 hours; then hourly followed by appropriate titration depending on the clinical response to treatment. However, the treatment regimen will vary depending on the type and severity of the initial presentation.

If Treatment Fails

If medical treatment fails, the next step may be a TKP. However, in the post-SIK syndrome cornea, removing the disk poses the same risks as trying to reach the interface: dropping the disk into the anterior chamber and causing an intraocular infection. In a TKP the surgeon's objective should be to remove the sandwich as a whole without disrupting the interface.

SIK syndrome is a new entity unlike any other corneal infection we've seen so far. Any opacity in the interface after STCT should make the surgeon suspicious and cause him to monitor the patient closely.

Dr. John is a clinical associate professor at

1. John T. Selective tissue corneal transplantation: A great step forward in global visual restoration. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 2006:1;5-7.