WHEN IT COMES TO CHOOSING THE best therapy for our glaucoma patients, we're fortunate to have a lot of large-population study data we didn't have 10 years ago. However, in practice, what really matters is what's going to work for the unique person sitting in the chair. That requires real communication and awareness of each patient's lifestyle and limitations.

Without this, compliance is likely to become a problem. Plus, dissatisfaction could drive the patient to another practice. A recent survey of 4,300 glaucoma patients conducted by the Glaucoma Research Foundation revealed that 72 percent of those surveyed never changed doctors over the entire course of treatment. But of the 28 percent that did, the most common reason given was "poor communication."

Here are a number of strategies that can help you improve communication and adapt treatment to a patient's unique circumstances.

Motivating the Patient

Reasons for a lack of patient compliance—forgetfulness, complexity of the regimen, cost and other factors—are easy to understand. But all of these factors are trumped by the issue of motivation. A highly motivated patient will surmount a host of obstacles to be compliant; an unmotivated patient probably won't comply no matter how easy it might be to do so. Not surprisingly, to motivate your patients, communication is key.

• Make sure the patient understands the disease. A surprising number of glaucoma patients don't understand much about the disease. They may confuse it with cataract; they don't realize that it can lead to blindness; they don't grasp the connection between intraocular pressure and loss of vision. Without this understanding, patients are unlikely to be motivated to follow your treatment protocol.

Without this, compliance is likely to become a problem. Plus, dissatisfaction could drive the patient to another practice. A recent survey of 4,300 glaucoma patients conducted by the Glaucoma Research Foundation revealed that 72 percent of those surveyed never changed doctors over the entire course of treatment. But of the 28 percent that did, the most common reason given was "poor communication."

Here are a number of strategies that can help you improve communication and adapt treatment to a patient's unique circumstances.

Motivating the Patient

Reasons for a lack of patient compliance—forgetfulness, complexity of the regimen, cost and other factors—are easy to understand. But all of these factors are trumped by the issue of motivation. A highly motivated patient will surmount a host of obstacles to be compliant; an unmotivated patient probably won't comply no matter how easy it might be to do so. Not surprisingly, to motivate your patients, communication is key.

• Make sure the patient understands the disease. A surprising number of glaucoma patients don't understand much about the disease. They may confuse it with cataract; they don't realize that it can lead to blindness; they don't grasp the connection between intraocular pressure and loss of vision. Without this understanding, patients are unlikely to be motivated to follow your treatment protocol.

|

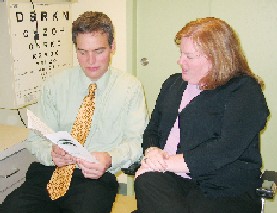

| Dr. Noecker explains the disease and its consequences to a glaucoma patient to help ensure that the patient understands the need for treatment. |

• Show the patient that he's at risk for vision loss. As we know, glaucoma is very subtle until the bitter end, at which point you can't really do anything about it. In the early stages of the disease, patients usually don't notice the effects. They say, "I can wave my fingers off to the side and my vision's just fine." So even if they understand the nature of the disease, they also have to be convinced that they are at risk.

This means demonstrating two things: first, that visual problems are easy to miss because the visual system is designed to be redundant. (You can use the blind spot to illustrate how the brain "fills in the blanks" when visual data is missing.) Second, the patient needs to be convinced that he could lose vision. If possible, show the patient his visual field results, or scans from imaging devices like the OCT, HRT or GDx. Explaining the significance of deviations from the norm will give the patient a reason to take your medical advice seriously.

• Make sure the patient understands how the treatment will help. Be sure to explain how the drops work, and that long-term studies have proven them to be helpful. If the patient knows exactly what the drops are doing, and that clinical evidence proves they work, he'll be much more likely to use them correctly.

• Forewarn the patient about side effects. Unexpected discomfort may cause the patient to think that something is wrong, or feel that you didn't fully disclose the downside of treatment. That's not going to improve compliance.

Many practitioners don't realize that all these drops sting to some degree. (Try them yourself!) They all give you a foreign body sensation, and produce varying degrees of irritation. If we underpromise and overdeliver by warning the patient about this up front, the patient won't be surprised if irritation occurs. And if the patient isn't bothered, he'll be pleasantly surprised, or simply forget that you mentioned it. (I spend more time discussing this when a patient is taking medication for the first time.)

Contrary to what many practitioners believe, patients—at least motivated patients—don't mind side effects if the reason for taking the medication is clear, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation survey. Ninety-two percent of respondents said, "I want the eyedrop that lowers pressure the most, even if it causes red eye for a few weeks."

Because patients reported which medications they were taking, researchers also broke down the data to see whether there was a relationship between the therapy the patient was using and the reaction to side effects. Notably, reactions were about the same regardless of the therapy. About half the respondents said that burning and stinging were never an issue (regardless of which drop they were using). Only 5 or 6 percent said these were frequently or always a problem.

The results were similar for other side effects. Complaints about red eye were evenly distributed. Fifty or 60 percent of respondents said they rarely or never had dry eyes, regardless of what they were currently using; only 6 to 9 percent said it was always a problem, again not correlating to specific drugs. Likewise, the data from many long-term clinical trials shows variability between different medications in the incidence of side effects like hyperemia or red eye, but the dropout rates in these trials are almost identical regardless of the drop used.

This means that minor side effects are not a big factor for motivated patients. The key factor, of course, is motivation. Side effects will be much more irritating to a patient who doesn't see a reason to tolerate them.

This means demonstrating two things: first, that visual problems are easy to miss because the visual system is designed to be redundant. (You can use the blind spot to illustrate how the brain "fills in the blanks" when visual data is missing.) Second, the patient needs to be convinced that he could lose vision. If possible, show the patient his visual field results, or scans from imaging devices like the OCT, HRT or GDx. Explaining the significance of deviations from the norm will give the patient a reason to take your medical advice seriously.

• Make sure the patient understands how the treatment will help. Be sure to explain how the drops work, and that long-term studies have proven them to be helpful. If the patient knows exactly what the drops are doing, and that clinical evidence proves they work, he'll be much more likely to use them correctly.

• Forewarn the patient about side effects. Unexpected discomfort may cause the patient to think that something is wrong, or feel that you didn't fully disclose the downside of treatment. That's not going to improve compliance.

Many practitioners don't realize that all these drops sting to some degree. (Try them yourself!) They all give you a foreign body sensation, and produce varying degrees of irritation. If we underpromise and overdeliver by warning the patient about this up front, the patient won't be surprised if irritation occurs. And if the patient isn't bothered, he'll be pleasantly surprised, or simply forget that you mentioned it. (I spend more time discussing this when a patient is taking medication for the first time.)

Contrary to what many practitioners believe, patients—at least motivated patients—don't mind side effects if the reason for taking the medication is clear, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation survey. Ninety-two percent of respondents said, "I want the eyedrop that lowers pressure the most, even if it causes red eye for a few weeks."

Because patients reported which medications they were taking, researchers also broke down the data to see whether there was a relationship between the therapy the patient was using and the reaction to side effects. Notably, reactions were about the same regardless of the therapy. About half the respondents said that burning and stinging were never an issue (regardless of which drop they were using). Only 5 or 6 percent said these were frequently or always a problem.

The results were similar for other side effects. Complaints about red eye were evenly distributed. Fifty or 60 percent of respondents said they rarely or never had dry eyes, regardless of what they were currently using; only 6 to 9 percent said it was always a problem, again not correlating to specific drugs. Likewise, the data from many long-term clinical trials shows variability between different medications in the incidence of side effects like hyperemia or red eye, but the dropout rates in these trials are almost identical regardless of the drop used.

This means that minor side effects are not a big factor for motivated patients. The key factor, of course, is motivation. Side effects will be much more irritating to a patient who doesn't see a reason to tolerate them.

Other Ways You Can Help

Motivation isn't the only factor influencing compliance, but we can take steps to minimize the impact of some other factors.

• Get the patient to talk about his current lifestyle. You can help circumvent possible obstacles—but only if you know what they are. If a patient has arthritis, someone may need to help him with the drops. Maybe the patient can't afford the medication. Maybe other highly distracting events are happening, such as the death of a family member. Patients don't always mention these things to the doctor.

Getting the patient to talk may also reveal problems that the patient doesn't realize are related to the medication. Maybe the drops are causing a side effect, such as depression. Daily tasks may be undercut by blurred vision, or trouble adapting to light and dark. Patients may start avoiding activities that they have problems with, such as driving at night. As a result, knowing what activities they're avoiding can be important information.

A skilled observer can pick up some of this just by watching the patient, but it's very helpful to get the patient to talk. I don't grill the patient; I just ask a casual question like "How're you doing with driving?" "Is there any change since your last visit?" "Are you doing okay with reading?" "Are you seeing everything you want to see?" It's also good to ask what they've been doing since the last visit. Some will say they took a lovely holiday; others will say they've been in the hospital having open-heart surgery.

Although I prescribe medications 95 percent of the time, there is a subset of patients for whom medications aren't a realistic option. If the conversation about lifestyle makes it clear that this is an issue—for example, if someone has limited mental capacity and is trying to live on his own, or if he's 200 miles away from the nearest pharmacy—I'll consider going to laser or incisional surgery.

• Minimize and simplify the protocol. Adding complexity to a regimen decreases compliance, so it makes sense to minimize the number of medications that the patient has to take on a daily basis. When one medication doesn't meet my goal, I try switching medications rather than adding more meds. If necessary, I'll add a second drop, but I find that compliance drops off rapidly after two medications that have to be taken daily at different dosing intervals.

It's important to be realistic about what a person can manage. In truth, I don't know how good I'd be at taking a medication four times a day if I didn't think my glaucoma was that bad and my schedule was really busy.

• Schedule medication timing to fit the patient's lifestyle. I always ask what time of day is easiest for the patient to take medication. In the case of a hypotensive lipid, the recommended dosing is at nighttime, but clinical trials have found potent IOP reduction whether it's used in the morning or at night. Some patients are more likely to remember the drops if they use them in the morning when they brush their teeth. Also, an older patient may have a family member who visits once a day, perhaps at lunchtime—it's reasonable to put the drop in then.

• Be aware of the patient's response to the diagnosis. When first hearing that they have glaucoma, or upon hearing that it's getting worse, some people may think, "I'm doomed" and feel like they have no control. Conversely, some people say, "I'm fine now ... I don't have any problems. Why should I mess around with this?"

It's part of our role to understand where each person is in his response to this, because these attitudes can have a dramatic effect on motivation.

• Watch the patient instill drops. It's amazing how much trouble people can have putting in their drops; even if they eventually get it in the eye, they may waste a lot of medicine. (Valued by weight, some of these medications are more expensive than gold!) Medicine running down the cheek may also lead to side effects on the skin.

|

| Have the patient instill drops while you watch. Poor technique can lead to side effects on the skin, wasted medication, frustration and poor compliance. |

To avoid these problems, have the patient instill drops in your office, so you can observe and offer the patient advice. For example, if a patient just can't get the drop in, I may have him lie on a flat surface, put the drop in the corner of the eye and then turn his head so that gravity instills the drop in his eye.

• Suggest ways to prevent side effects. Some patients get skin changes from a medication, such as an allergic reaction or skin pigmentation. I always advise patients to wipe off the skin around their eyes after putting the drops in. This seems to decrease overall irritation as well.

• Make sure the patient will tolerate the medication. I give the patient a sample of the medication and ask him to let me know if he has trouble tolerating it. This can prevent months of non-compliance.

• Help minimize barriers to medication access. It's important to ask patients how they plan to acquire the medication. Patients don't always volunteer that money is tight, and the way the patient purchases meds can play a major role in compliance.

A lot of our patients use mail order; others go to the local drugstore, where they probably pay more for the same medication. For some patients, saving money and/or having more of the medication on hand is important. If the patient is on a co-pay system, I usually prescribe a bigger-sized bottle so they get more for a single copay. For others on a tight budget with no co-pay, buying in smaller quantities may be a necessity, even if the price per unit is higher.

I often suggest alternatives for medication purchase when appropriate for the patient. This can have a big impact on compliance. (Also, remember that the drug companies have support programs for patients without any purchasing resources.)

• Explain what will happen next and involve the patient. Having a plan helps make patients feel that they're involved in the management of the disease, rather than just following orders. Before patients leave the office I say: "We'll see you again in four months. When you come back we'll do another visual field test, we'll check that your eye pressure is low enough and we'll image your optic nerve and make sure it's not getting any thinner. That way we can be sure that your vision has stabilized and isn't getting any worse." This helps patients feel that they're part of the plan. That adds to their motivation and the likelihood that they'll use their meds as intended.

• Provide written instructions. Make your instructions as concrete as possible and give them to the patient in written form. Even the brightest person may go to the doctor, sit there and listen and think everything makes perfect sense, and then walk out the door and find he can't remember some of what was said.

• Suggest ways to prevent side effects. Some patients get skin changes from a medication, such as an allergic reaction or skin pigmentation. I always advise patients to wipe off the skin around their eyes after putting the drops in. This seems to decrease overall irritation as well.

• Make sure the patient will tolerate the medication. I give the patient a sample of the medication and ask him to let me know if he has trouble tolerating it. This can prevent months of non-compliance.

• Help minimize barriers to medication access. It's important to ask patients how they plan to acquire the medication. Patients don't always volunteer that money is tight, and the way the patient purchases meds can play a major role in compliance.

A lot of our patients use mail order; others go to the local drugstore, where they probably pay more for the same medication. For some patients, saving money and/or having more of the medication on hand is important. If the patient is on a co-pay system, I usually prescribe a bigger-sized bottle so they get more for a single copay. For others on a tight budget with no co-pay, buying in smaller quantities may be a necessity, even if the price per unit is higher.

I often suggest alternatives for medication purchase when appropriate for the patient. This can have a big impact on compliance. (Also, remember that the drug companies have support programs for patients without any purchasing resources.)

• Explain what will happen next and involve the patient. Having a plan helps make patients feel that they're involved in the management of the disease, rather than just following orders. Before patients leave the office I say: "We'll see you again in four months. When you come back we'll do another visual field test, we'll check that your eye pressure is low enough and we'll image your optic nerve and make sure it's not getting any thinner. That way we can be sure that your vision has stabilized and isn't getting any worse." This helps patients feel that they're part of the plan. That adds to their motivation and the likelihood that they'll use their meds as intended.

• Provide written instructions. Make your instructions as concrete as possible and give them to the patient in written form. Even the brightest person may go to the doctor, sit there and listen and think everything makes perfect sense, and then walk out the door and find he can't remember some of what was said.

Dr. Noecker is an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh. He is also vice chair and director of the glaucoma service.