For years, penetrating keratoplasty was the go-to procedure for corneal transplants. Then came disease-focused transplant techniques—endothelial and lamellar keratoplasty—that supplanted the “one-size-fits-all” approach of traditional PK with increasingly refined surgical options, tailored to specific indications. The number of endothelial transplants surpassed full-thickness transplants around 2012.1 Since then, penetrating keratoplasty has seen a slower increase in surgery volume, compared to EK.1-4,8,9 But this trend doesn’t mean that penetrating keratoplasty is going away; PK just has fewer indications than before. Here, experts discuss the shifting landscape of keratoplasty procedures, concerns with full-thickness transplants and when a full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty is still warranted.

The Changing Landscape

The Eye Bank Association of America reported for 2019 that the number of penetrating keratoplasty grafts increased by 0.4 percent (to 17,409 grafts) and endothelial keratoplasty increased by 1 percent (to 30,650 grafts), largely due to a 23-percent increase in DMEK procedures.1 “That’s almost double the volume of penetrating keratoplasty,” says Thomas John, MD, clinical associate professor at Loyola University Chicago and in private practice in Oak Brook, Tinley Park and Oak Lawn, Illinois. “What’s happened over time is that we had one choice—PK—and now we have much more advanced, selective corneal transplant options for lamellar or endothelial keratoplasty.”

“Just 15 years ago, keratoplasty was almost exclusively penetrating keratoplasty,” says Kenneth R. Kenyon, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at Tufts University School of Medicine/New England Eye Center and faculty member at Harvard Medical School and the Schepens Eye Research Institute. “Then came the revolution, as both anterior and posterior lamellar techniques were devised to manage tissue-specific corneal issues. Now in the United States, endothelial keratoplasties—DSAEK or DMEK—comprise at least 50 percent of the keratoplasties.

“Anterior lamellar keratoplasty for corneas with healthy, functional endothelium, also has an increasing role, particularly for keratoconus and stromal scarring from trauma and microbial keratitis,” Dr. Kenyon continues. “Especially in the developing world where these conditions are most prevalent and where corneal donor tissue remains undersupplied, ALK is advantageous, since it’s rejection-free and doesn’t require the highest quality of corneal donor tissue material. In such circumstances, perhaps 25 percent of transplants utilize ALK techniques.”

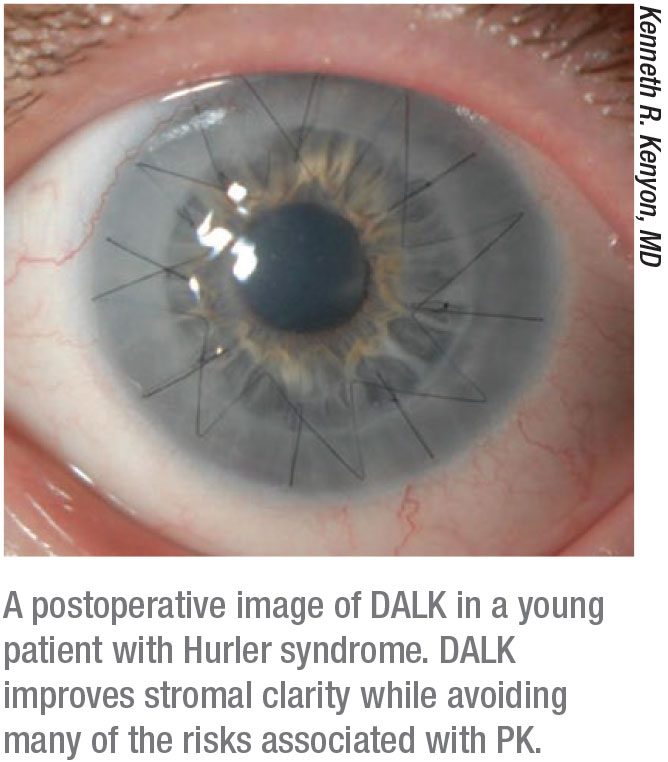

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, adds that anterior lamellar grafts existed alongside penetrating grafts for decades, “but they were used at a very low level for a long time, because the techniques and results weren’t very good. When the big bubble technique came out, we started doing more DALKs, which is a better procedure than PK—the main advantage being that there’s no endothelial rejection. Having said that, it’s a tricky procedure and many believe the visual results aren’t as good as PK.”

PK comprises perhaps 30 percent of cases, according to Dr. Kenyon. “These cases have either a combination of stromal scarring, thinning, ulceration or distortion that’s not amenable to DALK and is often accompanied by endothelial failure, which requires more than a DSAEK. For such patients, penetrating keratoplasty remains the appropriate strategy.”

|

Sometimes Less is More

|

While penetrating keratoplasty still has a role to play in the surgeon’s toolkit, there are several reasons why it’s used less often today. Newer methods of corneal transplantation aim to maximize visual outcomes and recovery while using less tissue and achieving lower rejection rates.

Generally speaking, surgeons say that the less manipulation of the eye, the better. Dr. John says that unlike lamellar or EK procedures, secondary glaucoma can be an issue with penetrating keratoplasty. In terms of graft rejection, “it appears that the amount of new tissue put in is directly related to the amount of rejection,” says Dr. Rapuano. “A big, full-thickness graft has a much higher chance of rejection than a smaller DSAEK or DMEK graft.” With anterior lamellar grafts, rejection is nearly nonexistent.

Here are some of the drawbacks to PK that encouraged innovation in less-invasive methods:

• Risk of rejection. “Less immune graft rejection is perhaps the most compelling advantage of not doing PK,” says Dr. Kenyon. “Long-term studies of DSAEK and DMEK procedures have clearly proven superiority in this respect. The PK failure rate due to rejection might be around 10 to 15 percent within a decade, depending on diagnosis and case-specific risk factors, since grafts for uncomplicated corneal edema or keratoconus enjoy high success rates, whereas a chemical burn with stem cell deficiencies or herpes keratitis with recurrence risks have higher risks for graft failure. The prognostic spectrum is very broad and often multifactorial.

“Painting with such broad strokes, let’s suggest that the PK failure rate from rejection might be 15 percent within 10 years, whereas DSAEK reduces that risk to about 5 percent,” he continues. “The real game-changer is the DMEK procedure, which reduces the rejection risk to about 1 percent—again, recognizing that DMEK is typically performed in the most favorable prognostic groups such as endothelial dystrophy or dysfunction, absent other risk factors. Nonetheless, such low rejection rates are stunningly advantageous.”

• It’s an open-sky procedure. Though expulsive hemorrhage is rare, experts say it’s still an operative risk. “Whenever you do PK, one thing to keep in mind is that unlike lamellar procedures, which are usually closed procedures, PK is an open-sky procedure,” explains Dr. John. “Hence, with PK, there’s always the risk of potential intraocular expulsive hemorrhage. In those cases, if the surgeon doesn’t act fast enough, you can lose the intraocular contents on the table. To avoid this potential, devastating complication, it’s important to minimize the time period between taking the patient’s cornea off and grafting the donor tissue. If you’re performing the procedure while your patient is under general anesthesia, ensure your patient is paralyzed. Expeditiously place the first four to eight interrupted sutures so that the corneal opening in the patient’s eye is closed. If, during the procedure, for whatever reason, there’s a sudden increase in the intraocular pressure, you can avert a possible expulsive hemorrhage and thus prevent the intraocular contents from coming out. Quick surgical action is required under pressure. Place the donor tissue and quickly suture at least the first four, but optimally, the first eight sutures. Sometimes the situation may even demand placing your thumb on the corneal opening to temporarily occlude it.”

“The patients who are at the highest risk for expulsive hemorrhage tend to be older or those with glaucoma, cardiovascular disease, potential bleeding issues or hypertension,” adds Dr. Rapuano. “In cases like these, you might consider a full-thickness transplant too dangerous. Though they may not be perfect EK candidates, you could try an endothelial graft and improve the vision a good amount, but it might not end up being 20/20, as it could have been with a PK.”

• Induced astigmatism. When it comes to visual outcomes, PK takes a backseat to EK. In endothelial procedures, the stroma remains unchanged; surgically induced astigmatism isn’t as much of an issue as it is with PK. “Even with intraoperative keratometry and refractometry, induced astigmatism remains a major challenge for PK,” says Dr. Kenyon, who refers to the process of selective suture removal and/or adjustment as “suture roulette.” He says, “Despite attempting to place sutures of even tension and distribution, the corneal curvature is still distorted, and so-called ‘sutures out’ astigmatism may require a year or more to stabilize. In contrast, slipping in the ‘little gift that keeps on giving’ of healthy endothelial cells, à la DSAEK or DMEK, only minimally alters the refractive status of the eye. Hence, both the rapidity of visual recovery and minimal refractive shifts are major advantages for endothelial keratoplasty.”

Intraocular keratoscopy can help a surgeon to qualitatively visualize the corneal astigmatism and take steps during surgery to decrease it. “Intraoperative suture techniques are used to help distribute the tension appropriately for the running sutures, and also to add or remove interrupted sutures to decrease the surgically induced corneal astigmatism,” says Dr. John.

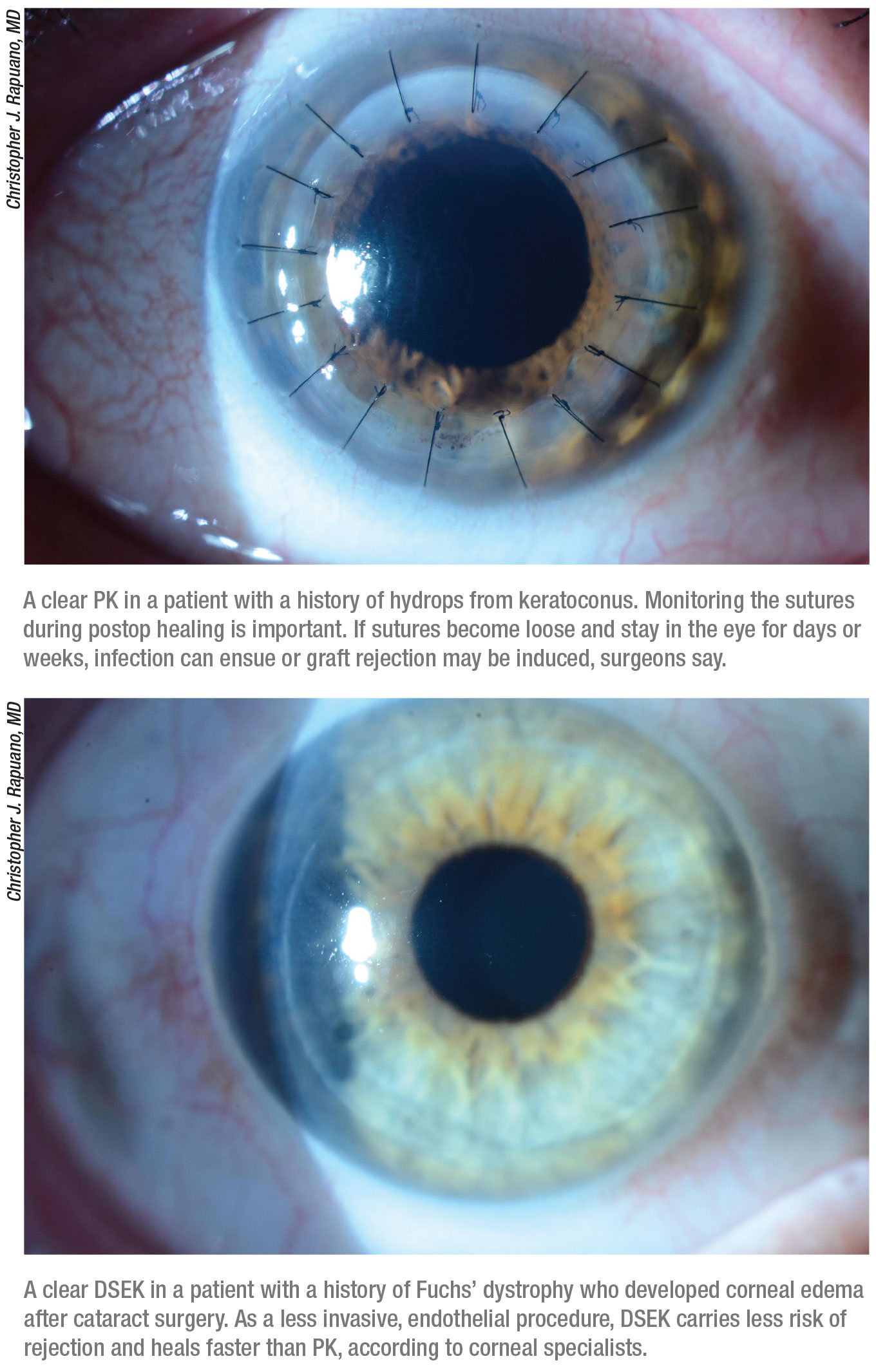

Dr. Rapuano notes that vigilant suture follow-up is also vital for postop healing. “Full-thickness transplants have a lot of sutures, so you want to make sure you follow those sutures,” he says. “If they become loose, take them out quickly. Patients need to be told that if they have foreign body sensation or scratchiness or feel like there’s something in the eye, they have to come in right away. If a loose suture stays in for days or weeks it can cause infection or induce rejection. The office staff also needs to be informed that if a patient who had a transplant calls with these concerns, he or she needs to be seen right away.”

• Slow healing. Corneal incisions are very slow to heal, Dr. Kenyon points out. “The wound strength of a corneal incision—and particularly of a full-thickness PK incision—isn’t great,” he says. “The wounds don’t heal rapidly for two reasons. First, the cornea doesn’t have any blood vessels, so the wound-healing process isn’t promoted by neovascularization. Secondly, we’re chronically using topical corticosteroids to reduce inflammation to prevent and/or treat rejection, which also inhibits stromal wound healing. As such, suture breakage or removal even years after PK can result in a major astigmatic surprise.”

“With lamellar grafts, especially posterior lamellar grafts, the wound is stronger, and it’s rare to have damage like a traumatic dehiscence,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Endothelial grafts are the strongest. But with a full-thickness transplant, the eye is weak forever. The wound can break if you’re poked in the eye, and if you’re poked hard enough, the inside of the eye can fly out, resulting in blindness. We see PK dehiscences a couple times a week at Wills. Patients may fall or get hit in the eye and that’ll open their transplant from 10 or 20 years ago.”

“Given reduced stromal tensile strength, PK eyes are always more vulnerable to damage even consequent to relatively minor mechanical trauma,” agrees Dr. Kenyon. “This can range from the non-vision-threatening, where a minor wound dehiscence requires additional suture replacement, to the catastrophic, where extrusion of iris and lens/IOL with potential expulsive choroidal hemorrhage can be irreversibly blinding. These are low-probability events, but they’re high-risk in terms of severity of consequences.”

|

Postop Complications

Ocular surface disease, induced astigmatism and graft rejection rank among the top causes of problems after full-thickness transplants. “Other complications are specific to the reason for the transplant in first place,” Dr. Rapuano explains. “If you’re doing a PK for a perforated ulcer due to infection, you have to worry about infection after the surgery. If you’re doing it for herpes simplex, you’ll be looking for a scar, and the patient may have inflammation. You’ll also worry about healing, since the nerves are severely damaged in eyes after herpes simplex or herpes zoster. A recurrence of herpes, especially herpes simplex, after a transplant is another concern.”

Who Still Needs PK?

“When the problem is throughout the entire cornea, that’s where a full thickness graft would be most useful,” Dr. Rapuano says. Here’s a closer look at some major situations in which PK is still necessary:

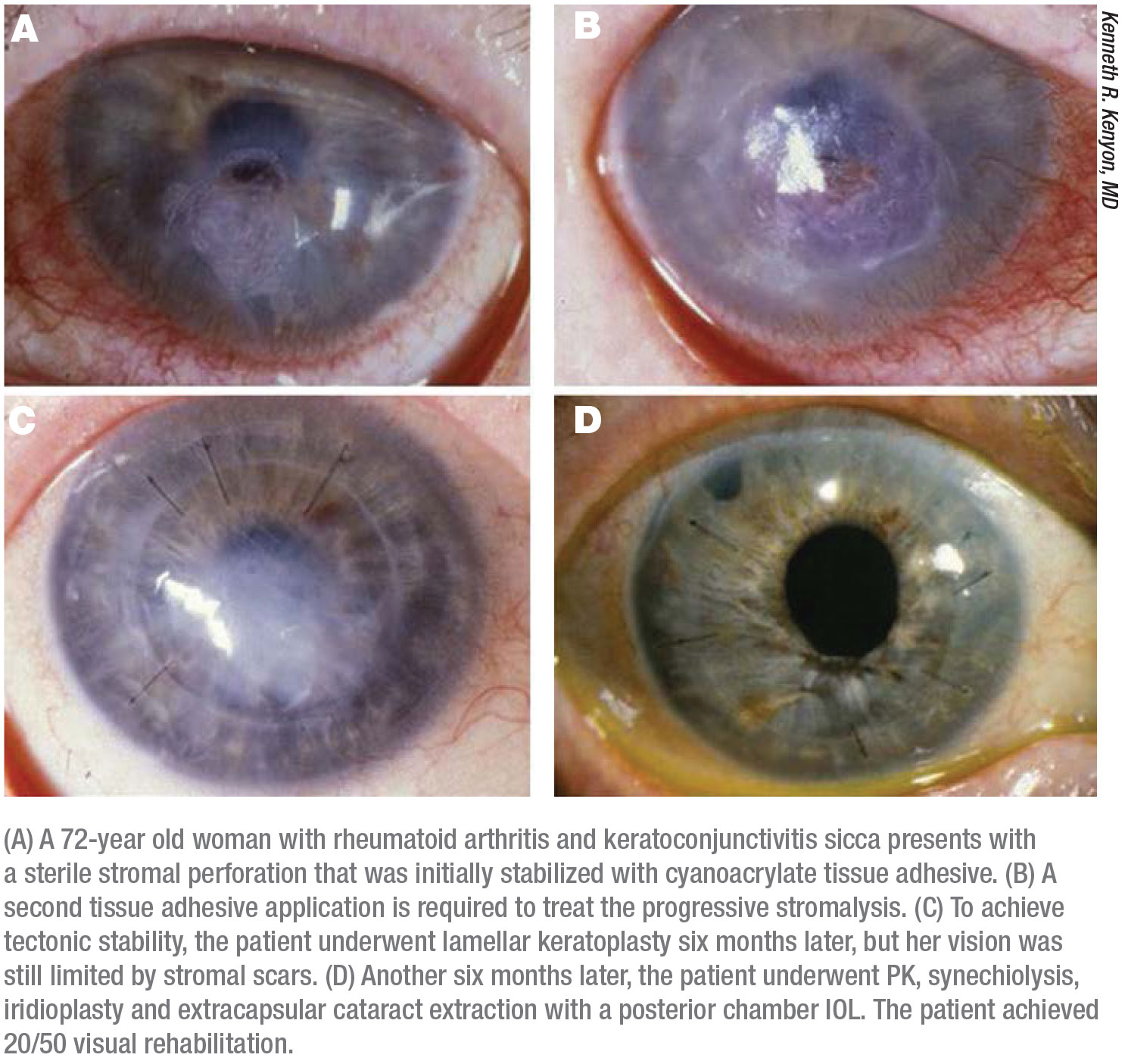

• Both the stroma and the endothelium have severe damage. Corneal melts, perforated corneas, stromal scarring, corneal edema5 and stromal thinning in the presence of endothelial cell dysfunction usually indicate PK. Additionally, Dr. John says, “infected corneal ulcers that don’t respond to intensive antibiotic treatment, where the infection expands toward the limbus, will often need PK as a therapeutic approach (therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty, TPK) to save the globe.”

In severe cases, such as in eyes with extensive infectious sclero-keratitis or corneoscleral destructive inflammatory or autoimmune disorders, extremely large-diameter corneal transplants (10 to 14 mm), sometimes including limbus and sclera, are mandatory to save the globe, says Dr. Kenyon. He adds, “I call these ‘commando’ procedures because they serve as ‘Hail Mary’ efforts in a desperate effort to save the eye in hopes of returning subsequently for conventional PK plus whatever additional adjunctive anterior segment reconstructive efforts are required for visual rehabilitation.”

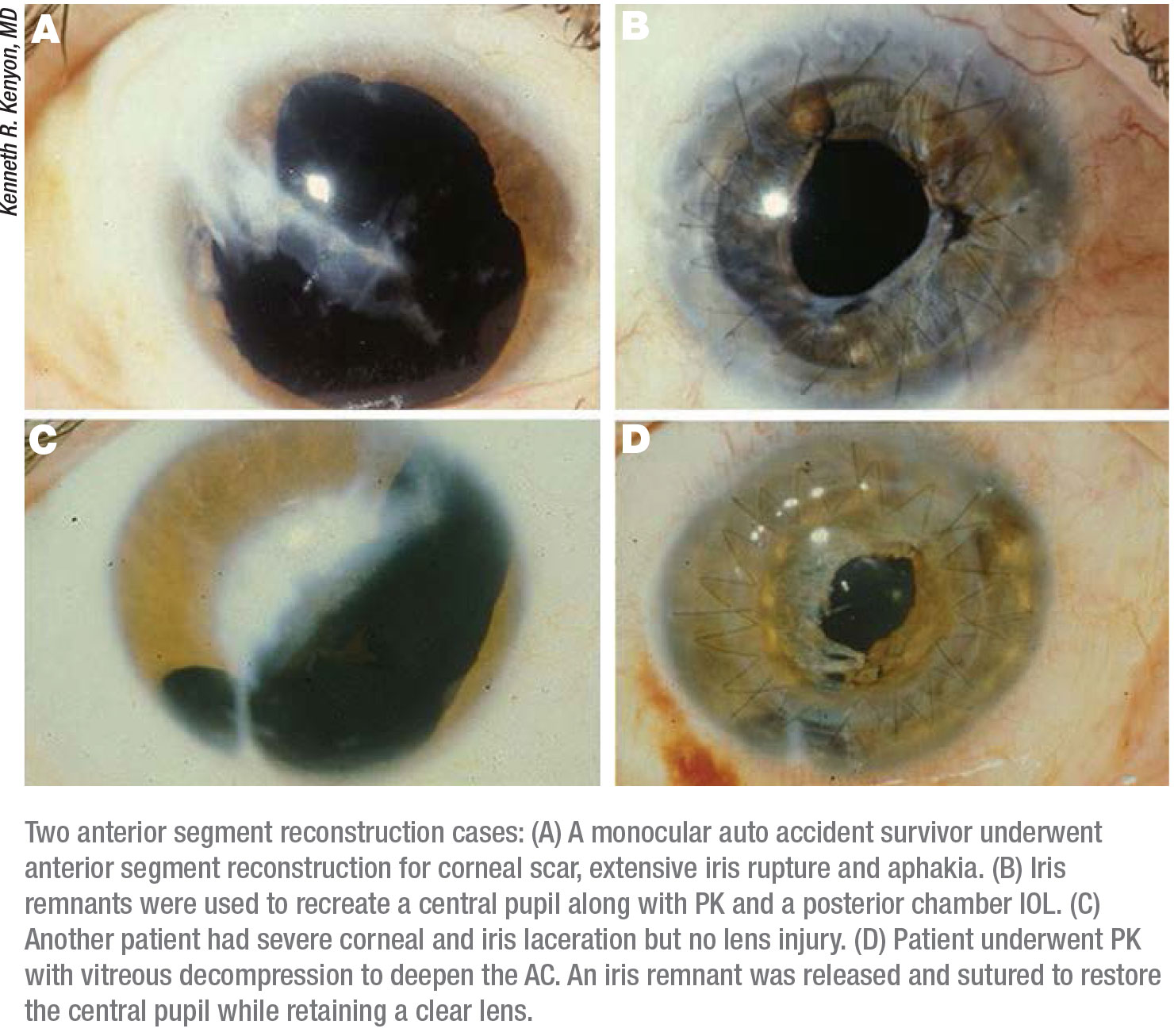

• Trauma to the eye. “If there’s been a laceration of the cornea, and it was repaired and healed up, you’re often left with a full thickness scar in the cornea,” notes Dr. Rapuano. “That’s a full thickness problem, and typically a penetrating graft would work the best.”

Your ability to restore the tissue may dictate your choice of transplant procedure, surgeons say. “For primary trauma, PK, although not often indicated, must be performed if major corneal tissue loss or ulceration doesn’t allow anatomical restoration with conventional suturing and adhesives,” says Dr. Kenyon. “Moreover, it’s imperative to deal simultaneously with all other aspects of anterior segment damage such as iris tears or dialysis, irido-corneal synechiae, lens rupture or subluxation/dislocation, intraocular foreign body removal and/or vitreous prolapse or hemorrhage.6 The ‘open sky’ approach, in concert with keratoplasty, at the very least facilitates access and exposure to the entirety of the anterior segment.

“Most post-trauma procedures that require complex reconstruction are performed months or even years after the original trauma,” he continues. “Then you’re working with an anatomically stable eye that’s uninflamed and infection-free, may have undergone ocular surface restoration for limbal stem cell deficiency, has its intraocular pressure under control and is appropriate for a scleral- or iris-fixated IOL. I term corneal transplantation in these challenging scenarios ‘PK Plus,’ as the multiple aspects of anterior segment reconstruction are more readily achieved with the corneal ‘lid’ off than when completing the procedure with the almost incidental aspect of replacing a new cornea. Such concerted efforts are usually without additional complication risk. To the contrary, they’re most often of visual, anatomical and cosmetic benefit.”7

• Multiple, prior glaucoma or cataract surgeries. “This subgroup includes eyes that have had multiple surgeries for glaucoma and cataract with tube shunts and filters, extensive peripheral synechiae that need to be lysed or pupils that need to be reconstructed,” says Dr. Kenyon. “These eyes are also traumatized by virtue of having undergone so many prior procedures. Although some cases that only involve corneal edema remain amenable to DSAEK/DMEK, for situations where we must also reposition or replace a tube shunt, lyse extensive iridocorneal synechiae, reconstruct a pupil and/or replace an IOL, the open-sky strategy of PK remains most definitively applicable.”

• Multiple, prior keratoplasty or keratorefractive surgeries. Dr. John says that “patients with failed DALK or DMEK transplants may also be potential candidates for PK, so as to avoid doing the same procedure over again. For those keratoconus patients with extreme corneal thinning, DALK may not be safe, and PK may be a better choice.”

Dr. Kenyon adds, “These cases largely comprise a miscellany of situations involving prior penetrating keratoplasties, typically for keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration, which over many years have had progression outside the limits of the prior transplant and thereby present with resultant high astigmatism and/or ectasia that cannot be visually remedied, even with scleral contact lenses. Severe post-LASIK ectasia or, rarely, corneas that have had overly aggressive radial keratotomy surgery are also best remedied with PK, not only to restore corneal clarity but also to restore more normal corneal contour within the range of refractive correction possible with spectacles or contact lenses.”

|

PK is Here to Stay

“There still are definite indications for full-thickness transplants, though less so now than 25 years ago,” says Dr. Rapuano. “The fellows at Wills get a lot of experience with full-thickness transplants. I think it’s still important for training programs to train their fellows on full-thickness procedures.”

Dr. John agrees. “In the corneal surgical arena, it appears that there will always be room for penetrating keratoplasty. When the visual axis is compromised by a full-thickness central corneal scar, it cannot be corrected by anything except a full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty. When PK is not a surgical option, in those subsets of patients, an artificial cornea such as the Boston Kpro may be considered.”10

“In the span of just two decades, corneal transplantation has remarkably evolved and advanced from the PK-for-everybody era to the selective keratoplasty strategy for disease-focused management,” Dr. Kenyon says. “Today, the tool box of the ‘Compleat Keratoplaster’ must necessarily contain the skillset from having mastered DALK and DSAEK/DMEK as well as having retained ‘PK Plus’ for the multiplicity of specific tissues and issues he or she encounters. Such creative choreography represents remarkable progress as well as promise for corneal transplantation in its many themes and variations.” REVIEW

Drs. John, Kenyon and Rapuano report no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Eye Banking Statistical Report 2019. Eye Bank Association of America. https://restoresight.org/what-we-do/publications/statistical-report.

2. Year in Review: Statistical Report 2015. Eye Bank Association of America 2015:29.

3. Year in Review: Statistical Report 2016. Eye Bank Association of America 2016:39.

4. Year in Review: Statistical Report 2017. Eye Bank Association of America 2015:5.

5. Schein OD, Kenyon KR, Steinert RF, et al. A randomized trial of intraocular lens fixation techniques with penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmol 1993;100:10:1437-43.

6. Kenyon KR, Kenyon BM, Starck T, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty and anterior segment reconstruction for severe ocular trauma. Ger J Ophthalmol 1994;3:2:90-9.

7. Kenyon KR, Starck T, Hersh PS. Penetrating keratoplasty and anterior segment reconstruction for severe ocular trauma. Ophtahlmol 1992;99:3:396-402.

8. Price MO, Price FW. Endothelial keratoplasty: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010:38:128-40.

9. Melles GR, Ong TS, Verver B. et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). Cornea 2006;25:987-90.

10. Ahmad S, Mathews PM, Lindsley K, et al. Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis versus repeat donor keratoplasty for corneal graft failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophtahlmol 2016;123:1:165-177.