The zonules holding the capsular bag in the eye function similarly, and when they’re weak or missing during surgery, complications result.

Zonular instability is no doubt the bane of many a cataract surgeon, as the risk for the cataract moving posteriorly or the vitreous moving anteriorly becomes higher, putting patients at risk for such complications as a retinal hole or detachment. In this article, expert surgeons share their best techniques for managing these cases.

Early Clues

Though you won’t often know the patient has weak zonules until you’re performing the procedure, you may see some clues during your preop exam. In particular, look for:

• History. Patients who are likely to have zonular weakness include those who have severe pseudoexfoliation with severe phacodonesis, high amounts of myopia, a history of trauma, Marfan’s syndrome, homocystinuria and retinitis pigmentosa.“You need to be ready to deal with that in the operating room,” says Brandon Ayres, MD, of Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia.

Also, you should let these patients know beforehand that their cataract procedures may be more complex. “On one side, we don’t want to scare patients because they typically have great outcomes,” says Brad Feldman, MD, of Wills Eye Hospital. “But I think it’s important to let them know about this condition.”

One additional note: When you do see a patient with loose zonules, it’s important to understand the etiology. “Sometimes there may not be an obvious reason,” says Mike Snyder, MD, of the Cincinnati Eye Institute. “Consider, though, that patients with undiagnosed Marfan’s syndrome or homocystinuria are at risk for aortic aneurysm and coronary artery disease, respectively. That’s why patients with loose zonules should be referred for a cardiac ultrasound or bloodwork and an echocardiogram.”

|

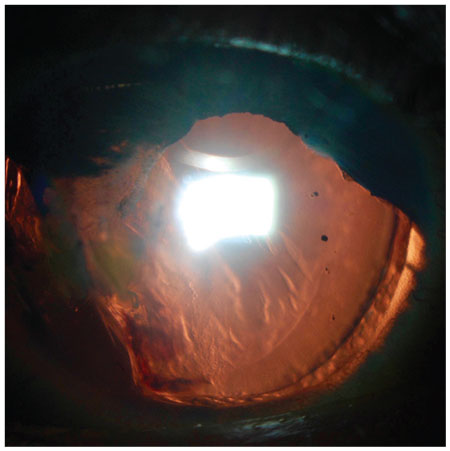

| Focal loss of zonular support, shown here at around 7 and 8 o’clock, should be noted preop in order to ensure a good result. |

• Slit lamp exam. Look for phacodonesis by having the patient in several directions and watch for lens movement. Dr. Feldman will repeatedly tap the slit lamp table with his fist to look for subtle lens instability (after warning the patient, of course). “Sometimes we’ll actually see the cataract jiggle. Sometimes we see shallowing of anterior chamber or the cataract tilted up against the iris,” he says. “Besides that, in cases where the patient is well-dilated, we may see areas where zonules are absent or are stretched.”

Iris defects should serve as a red flag, as well. “Whenever I see iris damage or a section of the iris that’s been modified, iridodialysis or something of that nature in the area where the iris is damaged, the support system may have been damaged,” Dr. Ayres says.

• Biometry. A deep anterior chamber also suggests possible risk. “The support system may already be weak, allowing the lens to sit farther back in the eye,” notes Dr. Ayres. “In that instance, vitreous gel may already be entering the anterior chamber.”

• Dilation. Keep in mind that the pupils of patients with pseudoexfoliation, Marfan’s or some other systemic conditions often don’t dilate fully.

Emergency Preparedness

Though you may see clues to zonular weakness during your preop work-up, it’s more likely that you’ll see them during the actual cataract procedure. “With most patients, the presence and degree of zonular instability is a surprise that reveals itself during surgery,” Dr. Feldman says.

So, surgeons say you should prepare your OR in advance. Specifically, you’ll want to have capsule support hooks, a capsular tension ring, triamcinolone (to visualize vitreous gel), and a vitrector on hand. “This is your emergency kit,” Dr. Ayres says. “This is what you want to have close access to.”

You should also feel comfortable performing anterior vitrectomy, because often the vitreous will come up around the equator of the lens. “Depending on what my suspicion is, in some cases it means doing the surgery in combination with the retinal surgeon in the event there’s no support for the zonules and we have to do a full-scale pars plana vitrectomy,” Dr. Ayres says. “That’s my last resort. I would rather take the cataract out [using the] anterior-segment approach.”

A Bad Start

The beginning of the capsulorhexis is one of the most common times you’ll identify zonular weakness that’s not iatrogenic, making the capsulorhexis more difficult to complete.

As you begin the procedure and fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic, look for a deepening of the chamber and focal areas in which the lens moves posteriorly or tilts. Consider using a heavier and more dispersive viscoelastic, such as Healon 5, which can help stabilize the eye and prevent vitreous from prolapsing around loose zonules. One precaution, however: Viscoelastics may put further pressure on the lens capsules and zonules, pushing the lens farther back and actually destabilizing the eye. “I’m cautious with the viscoelastic,” Dr. Ayres says. “If I need to improve my view of the lens, [ I use] iris retractors.”

Once you insert the cystotome, a taut capsular bag will puncture and tear, and the lens will remain still, but in cases of zonular instability, the lens may move and you’ll see wrinkles appear in the anterior capsule, Dr. Feldman says. As you approach that area and begin tearing the capsule, there’s poor countertraction; rather than continue tearing the capsule and pulling on the zonules, at this point you might want to consider a CTR or a capsular support hook.

Rings and Anchors

Standard CTRs are sufficient in cases that involve only mild weakness or only a few clock hours of weakness. Furthermore, Dr. Snyder says, use of a standard ring in areas of focal weakness, perhaps from trauma, helps ensure that the capsular bag stays even or secure without the need for fixation to the wall of the eye.

Standard rings also are indicated for individuals who have no current zonular weakness but who have conditions associated with zonular instability and are likely to develop it in the future. Having a CTR in place now makes later repair easier. “It’s much easier to stitch a ring for added security than it is to stitch an implant lens that doesn’t have a ring in place,” Dr. Snyder says.

If the patient has severe zonular instability, however, the capsular bag could be decentered. “In that case, we’re better [off] using something to keep the bag tethered to the wall of the eye,” Dr. Snyder says.

A modified capsular tension ring, such as the Malyugin/Cionni CTR (FCI Ophthalmics/Morcher), might be useful in such circumstances.

Because this ring has a ring around the capsulorhexis and a hook that has a small eyelet, Dr. Snyder says it’s possible to use a suture to affix the ring against the wall of the eye—creating a synthetic zonule of sorts.

Keep in mind that you can insert a CTR at any time during the procedure. “There’s no real rule as to when that CTR goes in,” Dr. Ayres says. “When you put those rings in, it can make cataract removal and cortical cleanup more challenging, but you need them to increase the safety of the case. You try to put them in as late as you can. It depends on how the case is going.”

In other instances, an Ahmed segment, in the shape of a 120-degree arc, might be a more appropriate choice, particularly if there is weakness in one area. However, if there is weakness in all areas, an Ahmed segment and a Cionni ring might be necessary. In cases of severe weakness, two segments may be required.

Other devices include the Malyugin Capsular Tension Ring (MicroSurgical Technology Inc.), which requires a smaller opening, and the AssiAnchor (Hanita Lenses), which you can insert into the capsular bag at 1.5 clock hours. In the latter device, the fixation piece is centrifugal, which allows the surgeon to exert torque on the capsular bag, unlike an Ahmed segment. “If you have an Ahmed segment or similar element in the equator of the capsular bag whose fixation tether is centripedal to the equator, [you] can induce torque, distort the bag and, sometimes, pull the element out of the bag entirely,” Dr. Snyder says.

Removing the Cataract

Cortical stripping is another time you may discover zonular disease you were not aware of. “When you remove the cortex, that’s when you have the most direct pressure on the zonules,” Dr. Feldman says.

For patients who have pseudoexfoliation, Dr. Feldman uses a sweeping motion to pull the cortex aside and direct forces in a peripheral motion rather than centrally, which would put more focal traction on individual zonules.

After the capsulorhexis, Dr. Feldman says extra hydrodissection is important to ensure the lens is free from the bag and that you’re not putting any torsion on the zonules. Dr. Ayres agrees, saying this allows the surgeon to rotate the lens material in the capsular bag to facilitate removal.

Splitting the lens into smaller pieces becomes much more difficult in individuals with zonular weakness, so Dr. Ayres chops the lens. “I lower all settings, pressures, and I use as much manual disassembly as possible. Instead of using phacoemulsification energy, I use mechanical energy to carefully remove the lens,” he says.

Dr. Feldman recommends a vertical chop technique to avoid putting pressure on the capsular bag and to allow the lens to come out easily in small pieces. “If you take a large piece of the nucleus out of the bag, especially if it’s one of the first segments you take out, if it catches on the anterior capsule or it’s not separated from other nucleus, it could put further pressure on the bag, causing more zonular dehiscence,” he says.

As you take out additional pieces, you may notice zonular instability that you weren’t aware of. “If there are poor equatorial zonules, you’ll start to see some of the extracapsular bag coming inward,” Dr. Feldman says “The lens itself can act like a capsular tension ring; when you take that volume out, the capsule can fall in on its own.”

Should this happen, you’ll want to use dispersive viscoelastic to prevent posterior capsule rupture, Dr. Feldman says. Also, fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic when you remove the phaco needle. “You never want the chamber to shallow. Otherwise you can make the instability even worse,” says Dr. Ayres. He adds that, once the nuclear portion of the lens is removed, you may want to place a CTR if you haven’t already done so.

The IOL

There currently is a debate as to what type of intraocular lens is most appropriate for patients with zonular instability. Dr. Ayres says he typically uses a single-piece acrylic lens that he can insert into the bag without any trauma. Another possibility is to place a three-piece IOL in the sulcus space.

“Many physicians will stay away from a premium IOL in these cases because there’s so much unknown,” Dr. Ayres says.

Experts say to keep in mind that if the patient has zonular instability due to pseudoexfoliation or if the patient is young, there’s a chance the lens may dislocate within seven to eight years postop. “For patients who are younger, I’m more apt to suture the lens,” Dr. Feldman says.

Also, when using CTRs, Dr. Snyder says to keep in mind that if you’ve secured the ring to the wall of the eye on one side, the zonules on the other side may become more unstable in the future. Also, polypropylene sutures may erode within seven to 10 years, requiring that the patient return to the OR for a patch graft. As a result, you probably want to avoid these in younger patients.

Postop Care

Because surgery on patients with zonular instability takes much longer, Dr. Ayres tends to use more steroids postop than he might in other patients. “As long as the cornea looks clear, I tend to put them on NSAIDs for six to eight weeks. Then you keep looking at them,” he says. “Also, if a vitrectomy was performed, monitor the patient for retinal tears or potential detachment.”

Cataract surgery in patients with zonular instability, though challenging, is an inevitability. “We’re all going to deal with these patients,” Dr. Feldman says. “And often it is a surprise. Every surgeon should be comfortable with getting the lens out in patients with zonular weakness, performing an anterior vitrectomy and having some go-to techniques to make sure the lens doesn’t fall posteriorly.” REVIEW