Adherence to any treatment protocol can be challenging for a patient, but managing glaucoma can be especially daunting. Despite the proliferation of surgical options and the exciting possibility of sustained-release drug delivery, many of our glaucoma patients still have to take eye drops. So, even when we do everything right in the clinic, our patients’ visual outcomes are largely dependent on how well the disease is managed after the patient leaves the clinic. Furthermore, it’s one thing to come up with a plan for a medication you have to take for a week; with glaucoma, we’re generally talking about patients taking medications for the rest of their lives. When you have to integrate something into your daily routine (and your budget) over the long term, it changes the nature of the challenge a bit.

The medications we have today are excellent, but there are still many ways that a prescription for glaucoma drops can go wrong, leading to short- or long-term intraocular pressure fluctuation:

• Even if your patients take their drops on time, they may use multiple drops trying to get them onto the eye and as a result, run out of their drops before the end of the month. If they’re not able to get a refill until the end of the month, they may go untreated for days. The American Glaucoma Society has successfully argued for legislation to make it possible for patients to refill a prescription before the end of the month when necessary, but needing frequent refills is disruptive, even if the financial burden is ameliorated.

• Patients may dose their medications late or forget to take them, resulting in gaps in therapeutic cover-age. Yes, it helps if the medication (such as a prostaglandin) only needs to be taken once a day. However, prostaglandins are often prescribed to be taken at bedtime, and I frequently have patients tell me that they fall asleep without remembering to take the drops. So even a once-daily drop may be problematic.

• Patients can miss the eye al-together when instilling the drops, and not realize it.

• The cost of the drops can lead individuals to not use them as often as prescribed.

• The patient might be managing multiple treatments for multiple medical conditions, leading to con-fusion and missed doses.

• A given patient might have difficulty understanding your written instructions or the information on the eye-drop bottle.

• Your patient may not grasp the reasons that treatment is necessary, leading to inconsistent (or nonexistent) use of the drops.

• Changing personal situations (a family crisis, for example) may push timely use of the medication to the bottom of the patient’s priority list—especially when the medication is addressing a potential future con-cern rather than a pressing current problem.

So: What can we do to help ensure that these obstacles don’t keep our patients from receiving effective treatment?

Effective Written Materials

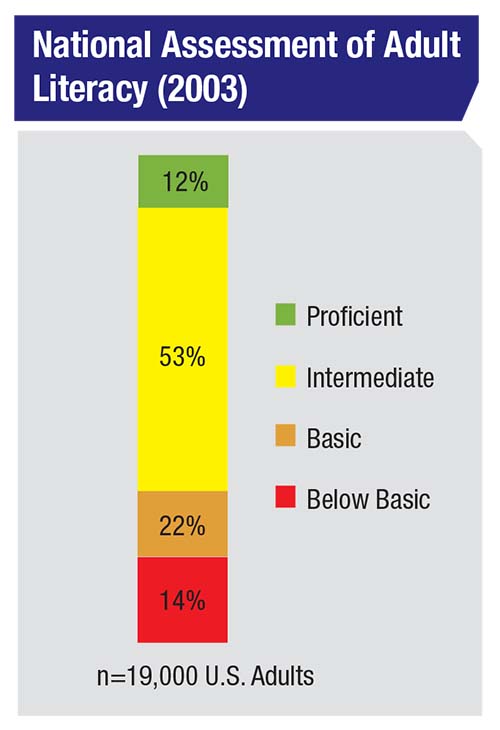

A significant part of getting patients to follow your instructions is clearly communicating the nature of the disease and what the patient needs to do. As already noted, patients can have trouble understanding written information and instructions. Back in 2003, the National Center for Education Statistics conducted an assessment of the literacy of 19,000 American adults; about one-third of them had only “basic” or “below basic” health literacy.1 People with “basic” health literacy skills may be able to read and write but not understand

health-care information—at least not well enough to make decisions based on that information. For example, one of the questions testing for basic health-literacy skills asks the test-taker to report when he or she should return to the office after being given an appointment reminder slip. People testing at the basic or below-basic level could not accurately answer the question.

Fortunately, the American Academy of Ophthalmology now provides us with excellent educational materials to meet the needs of patients with a wide range of literacy skills. Back in 1997, the AAO’s recommended educational materials were written at a ninth-grade reading level. In 2008 the readability of the materials was adjusted to an eighth-grade reading level. As of 2014, the materials are written at a sixth-grade reading level, making them accessible to a far larger group of patients. (If you’re still us-ing the older materials, it’s time to update.)

Some surgeons may worry that using simpler language and explanations could result in less engagement on the part of better-educated patients. This is apparently not an issue; a lot of work in the field of health-care literacy has shown that patients who have higher levels of literacy are going to ask questions to elevate the conversation to their level. They may ask which part of the trabecular meshwork is responsible for increased intraocular pressure, or ask for details about how the drop works. In response, we can start talking at that level as well.

|

| This study, conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics, found that about one-third of Americans function at basic or below-basic literacy. Educational materials need to take this into account in order to be helpful to the maximum number of patients. |

However, research in health literacy suggests that the opposite is not true: If we provide information that our patients can’t understand, they’re unlikely to tell us. They’ll just shut down and not engage. This is certainly not what we want when we’re dealing with a disease that’s going to affect these patients for the rest of their lives.

Another aspect of this that may not be immediately obvious is that we’re not just asking patients to comprehend potentially complex written language; there are also a lot of numbers involved. For example, we often ask patients to take a drop twice a day in the right eye and another drop three times a day in the left eye. Comfort with “numeracy” is an important part of functional health literacy, and lack of numeracy skills is often harder to recognize than difficulty with verbal and written information.

If You Create Your Own …

It’s worth noting that some doctors create their own patient-education materials. If you’re one of them, keep in mind some of the general principles of presenting clear health-care communications:

• Use an active voice, not a passive voice. For example, “Be sure to let your doctor know if you’re having trouble using your medications,” not, “Problems using your medications should be reported to your doctor.”

• Don’t fill pages with nothing but text. Looking at a page that contains dense passages of nothing but text is intimidating to anyone at any reading level!

• In terms of the content of your text, only use the level of detail that’s really necessary. Most patients just want to understand the broad strokes regarding what they’re dealing with.

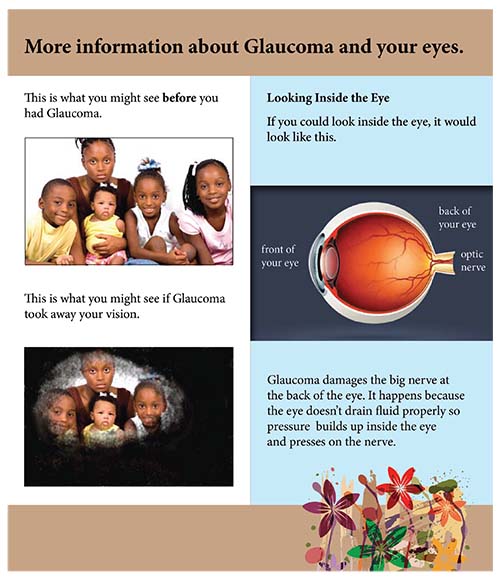

• Include clear graphics in your materials that illustrate important points—but again, without too much unnecessary information. As much as I love a detailed drawing of the trabecular meshwork depicting the various regions, this is probably neither helpful nor particularly interesting to most of my patients.

Making your materials patient-friendly is crucial, because once people get turned off by what you’ve given them, they’ll decide not to read it and that’s that. You’ve lost the opportunity.

Helping Patients Use the Drops

As everyone treating glaucoma understands, a central concern with glaucoma drops is making sure they reach the patient’s eye every day in a timely manner. Although it’s impossible to guarantee success in this arena, these strategies will shift the odds in your favor:

• Ask patients about problems they’re having taking the medications. The reality is that every person is different, and people may miss their medications for any of a number of reasons. Patients could have problems related to cost, circumstances, memory, managing multiple disease conditions, or missing the eye and running out of the medication before the end of the month. There’s only one way to know that there’s a problem, and if so, exactly what the problem is: We have to ask. If we don’t ask each patient what his or her particular challenges are, we won’t know.

The reality is, even if we intend to do this, we often don’t remember to do it. A couple of years ago I was one of 14 doctors involved in a multicenter study in which glaucoma patient visits, in both academic and private-practice offices, were video-recorded and the communication between doctor and patient was transcribed.2 I was surprised to find that, even though we were trying to be on our best behavior and knew we were being videotaped, we frequently didn’t ask about problems patients might have been having with their medications. (In fact, we often didn’t even discuss the nature of the disease.)

It turned out that we only asked our patients if they were having problems with the medications in 51 percent of clinic visits. Given that we knew we were participating in a study, this result might even be better than what you’d find in the field. (In fairness, the study went on for three years, and it’s hard to be on your best behavior for three years.)

|

| If you create your own educational materials for patients, be sure to follow a few basic rules to ensure good communication: Use an active voice; don’t fill pages with nothing but text; provide only the level of detail that’s necessary; and include clear graphics. |

Of course, once you do discuss these problems with patients and get a clear picture of the obstacles they’re facing, the next step is to do whatever you can to help them avoid or surmount those obstacles. These strategies will help:

• Always ask patients to show you how they instill their drops. If necessary, provide instruction. Some patients may do just fine on their own, but there’s enough research now to show that plenty of glaucoma patients aren’t able to get a drop onto their eye. For example, research done by Alan Robin, MD, has taught us that even among experienced drop users who deny any problems administering their drops, less than one-third can administer a drop successfully without contaminating the bottle tip.3 In my work at the Durham Veterans Administration, I’ve found that 10 percent of my patients—patients who were experienced drop users—could not get a drop into the eye at all under observation. And even if your patients succeed in getting a drop onto the eye without contaminating the tip, they may administer multiple drops in each attempt, causing them to run out of their medication before the next refill period is available. Furthermore, only a minority of patients report that anyone has ever shown them how to put in their eye drops.

So, ask your patients to demonstrate how they instill their drops. (We keep bottles of artificial tears in the clinic for this purpose, which is perfectly adequate to reveal any problems.) If a problem is obvious, show the patient (and/or the patient’s companion, if he or she is responsible for drop administration) the correct way to instill the drops.

• Ask if someone else helps your patient instill drops. We know from the work of Michael A. Kass, MD, that about 20 percent of patients don’t instill their own drops.4 This is not recent data, so the proportion of patients depending on assistance may be higher today, given that people are living longer and with multiple medical problems. We need to know if someone else is helping; if we’re giving instructions for instilling drops, we need to be giving them to the person who’s putting in the drops.

• Ask your patients what time of day they take their drops. If they say they take them right before bedtime, I ask whether they sometimes fall asleep before getting the drop in. You’d be surprised how many patients say, “Yeah, that happens a lot.”

Prostaglandins are usually pre-scribed to be taken right before sleep because of the hyperemia associated with them. If that’s a big issue for your patient, bedtime might be the better option, but for many of my patients a little hyperemia isn’t a big deal. Certainly, it’s better for a patient to take the drop in the morning and have a red eye than to not take it at all. I tell patients exactly that: If “red eye” is an issue, then take it at night, but if it’s not a big deal, take it in the morning to avoid forgetting it at bedtime.

• Suggest that patients pair taking their drops with other routine activities. Having patients pair dosing with an activity such as taking other medications, brushing their teeth or drinking a cup of coffee in the morning, can help.

• Suggest using a smartphone reminder app. There are lots of apps out there designed to help patients remember to take their medications. They can use this type of aid for all of their medications or just for their drops. (For a profile of some of these apps, see “Smartphone Apps: Aiding Compliance” in the June 2017 issue of Review.) Of course, if the patient has a companion who assists with taking the drops, both the patient and the assistant should use the reminder.

| Having patients pair their drop-taking with other routine activities can help. |

• If a patient has difficulty managing the eye-drop bottle, suggest using an inexpensive aid. Sometimes the problem isn’t that patients can’t get the drop in; they’re just struggling a little bit. Many health issues can get in the way of being able to administer eye drops properly. For example, if the patient has osteoarthritis, that can make it difficult to squeeze the bottle, or a hand tremor could make it difficult to aim the bottle at the eye.

There are some relatively simple aids that might be helpful in this situation. I’m most familiar with the AutoDrop Eye Drop Guide and AutoSqueeze Bottle Aid (both made by Owen Mumford) because they’re on the formulary in our prosthetics department. These aids only cost about $5. The former is a cup that’s open at both ends; the bottle is inserted into one end while the other end is placed over the eye. This can help patients who are struggling with aim. The latter aid has plastic wings that make it easier to squeeze the bottle; that can help those who have trouble with their grip strength. In addition, the two devices can be used together. (For a list of some additional options along these lines, see “Getting Drops Onto the Eye: Low-tech Solutions” in the September 2017 issue of Review.)

Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of evidence in the literature that these devices will make a huge difference. Different people have different prob-lems, so if you’re going to consider suggesting a device, you have to think about which one is most likely to help that patient; a one-size-fits-all approach to drop aids is probably not sufficient. Furthermore, you have to show them how to use it. Without a little instruction, your patient may never use the device.

Clearly, these aids are not a cure-all, but they can be helpful in some situations.

• If it’s clear the patient will have insurmountable difficulties instilling drops, consider pursuing a procedural intervention. Some-times a patient absolutely can’t put in the drops, or is struggling significantly, and there’s no companion available to help ensure that the drops get onto the eye. In that situation, you may want to move to a procedural intervention sooner rather than later. We all hope that in the near future we’ll have sustained-release drug delivery options that will remove drop administration from the equation. But in the meantime, we have laser trabeculoplasty and multiple surgical options. We can move to those things sooner if we know that a patient is struggling. REVIEW

Dr. Muir is an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham.

1. Committee on Health Literacy

Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Lynn Nielsen-Bohlman, Allison M. Panzer, David A. Kindig, eds. National Academies Press, 2004, p. 345.

2. Carpenter DM, Blalock SJ, Sayner R, Muir KW, et al. Communication predicts medication self-efficacy in glaucoma patients. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:7:731-7.

3. Hennessy AL, Katz J, Covert D, Kelly CA, Suan EP, Speicher MA, Sund NJ, Robin AL. A video study of drop instillation in both glaucoma and retina patients with visual impairment. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:6:982-8.

4. Kass MA, Hodapp E, Gordon M, et al. Part I. Patient administration of eyedrops: Interview. Ann Ophthalmol 1982;14:8:775-9.