Here, two surgeons who have used everything from smartphones to tablets to large-screen desktop units share their experiences and explain the reasons for their preference.

Using Tablets in the Clinic

“I like using handheld tablets,” says John S. Jarstad, MD, an associate professor of clinical ophthalmology at Mason Eye Institute at the University of Missouri School of Medicine. “I know some doctors won’t agree, but I think they’re very convenient for the technicians compared to sitting at a desk and typing in data.” Dr. Jarstad explains that he used electronic tablets in his previous practice for about three years before he moved to the University of Missouri School of Medicine. “We had an ophthalmology-specific EMR package when I was running my own practice, and we used the iPad in the clinic,” he says. “It worked pretty well in our practice.”

Dr. Jarstad says he likes many things about using electronic tablets in the clinic. “It was a little unwieldy to carry a tablet from room to room, so we didn’t do that,” he says. “We’d have the techs start the patients. They’d record the patient’s chief complaint and history using the iPad; then they’d record the visual acuity and eye pressure and dilate the patient. Everything was ready for me when I walked into the room. The tech would hand me the tablet with the screen set up to show me the appropriate data. Then a scribe would input data as I did the exam. By the time the exam was finished, all of the drop-down menus had been completed by the technician. That system got us close to the efficiency we previously had with our paper charts.”

Mounir Bashour, MD, PhD, FRCSC, FACS, is both an ophthalmologist and a biomedical engineer; he’s currently a partner in LasikMD, an ophthalmologist-owned chain of LASIK centers in Canada. Dr. Bashour says he’s worked with a number of electronic medical record programs, including some that used electronic tablets. “We did carry electronic tablets around with us in the office for a while,” he says. “But eventually we ended up creating our own EMR software, and we’re not using tablets today. Now we use large 27-inch touchscreens that let us make the most of our custom EMR; we have them in every room showing the patient’s data, so we don’t need to walk around with a smaller screen.”

Benefits and Drawbacks

Drs. Jarstad and Bashour note a number of issues to consider when choosing whether or not to use electronic tablets in your clinic:

• The impact of screen size. “In ophthalmology, screen size is an issue because you don’t want to be scrolling from screen to screen to see the data,” says Dr. Bashour. “Ideally, you want to be able to input all of your data on one screen. If you’re scrolling forward four screens to enter data and then scrolling back three screens, that’s not ideal.” (Dr. Bashour notes that at home he uses a pen-based Microsoft Surface, which can be used as either a notebook or a tablet.)

Dr. Bashour points out another problem with a small screen: smaller type fonts. “I’m in my 40s and getting presbyopia, so I have to wear reading glasses to use the tablet because of the smaller type,” he says. “That’s not a problem if you’re a young doctor, but it’s an issue if you’re a forty-something ophthalmologist.”

Dr. Jarstad says he likes using the electronic tablets despite this concern. “Some of our rooms have two large-screen monitors, which lets us put all the visual fields and OCT scans and retina photos on one screen and all of the EMR data on the other,” he says. “I appreciate that that’s a nice way to manage the information. Using tablets we sometimes have to miniaturize everything so we can look at a whole series of visual fields at a glance, for example. That can be challenging for those of us with presbyopia. But I like using a tablet anyway.”

• Your EMR template. The reality is that some EMR templates work better with a tablet than others. “To be honest, I don’t yet know if our university’s one-size-fits-all computer system will be able to adapt to what we need in ophthalmology, especially if we use handheld tablets,” says Dr. Jarstad. “I’ve tried a number of EMR systems; many of them have drop-down menus and use pointing and clicking to highlight different things. That avoids the need for a lot of writing. In contrast, the current system here at the university requires quite a bit of data entry and typing.”

Dr. Jarstad says their previous EMR system was set up to accommodate the small screen size. “It was organized into single pages that corresponded with each step of the exam,” he notes. “There was a tab at the top that you could highlight with the pen or your finger, dropping down the menu you needed at that point. We had one screen for the technician’s data; another for the slit lamp exam; one for the retina exam; and a place for the assessment and plan at the bottom. That was pretty efficient.”

• Managing auto-shutdown. Another issue when using handheld electronic tablets is the security protocol that shuts down the screen after a few minutes of non-use. “That was a hassle,” Dr. Jarstad says. “We had to input our password every time we walked into the room. But then we got devices that check your fingerprint, which is a big help. I highly recommend that. Otherwise, you’re spending 25 or 20 seconds at every station entering your password.”

• Weight and battery life. Dr. Jarstad notes that other issues are the weight of the device and how long the battery lasts. “The tablets we used were very big and heavy,” he says. They had the highest capacity for data storage and a larger battery to last through an eight-hour day, so they were heavier than a typical iPad might be. Of course, these factors improve with every new iteration of these devices, but they still need to be considered when gearing up to use tablets in practice. You definitely don’t want the battery to run out after four hours. We’d typically have a spare tablet charging at all times as a fallback, but most of the tablets we used had a robust enough battery to last through the clinic day.”

• The possibility of theft. “Some systems that work with electronic tablets are really nice, but they still have issues, including that the tablets can be stolen,” Dr. Bashour points out. “Theft is less likely if you put them in special cases with an alarm, but the alarm is sometimes triggered

|

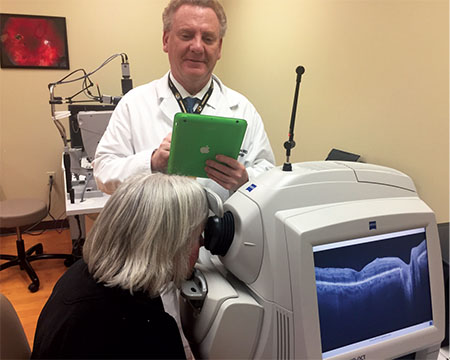

| Some surgeons find the portability of a handheld tablet offsets the disadvantage of a small screen—if the EMR program is designed for it. |

Regarding theft of the tablets, Dr. Jarstad says he recalls one occasion when a patient left with an iPad. “It might have been an honest mistake,” he notes. “In any case, it was useless without the password, and the patient returned it.” He says no doctors or staff members took the iPads home when they were using them in his clinic, because those who were allowed access to the system from outside the office could do so on their home computer or smart device for charting or scheduling.

• Some uses are very appropriate for a tablet. Dr. Bashour says his practice still uses electronic tablets for some things, including patient consent forms. “Tablets are convenient for that purpose,” he says. “We just hand them to patients. They can read everything on the screen and sign directly on the electronic tablet; that’s attached to their EMR record. Tablets are good for this because everyone’s familiar with them. Almost everybody has one at home, so patients know how to use them.”

• Surgeon comfort with a given device may relate to previous experience. Dr. Jarstad points out that a doctor’s preference will be affected by what he or she used in training. “We become accustomed to practicing medicine the way we did as residents,” he notes. “EMR in general is new to many of us. You just have to take the time to learn the system and practice with it; over time you get better and better at using it. If you’re not willing to do that, the only solution is to hire young, smart technology-wise people who are good at using electronic devices.”

What the Future May Hold

Will small, portable screens become more popular for clinic use in the future? “Tablets are useful if they fit the way you do things,” says Dr. Bashour. “Meanwhile, their usefulness may change as computer technology evolves. Hopefully, things will become more simple; we may have artificial intelligence following us around—perhaps a small robot taking notes. That’s a few years away, but it’s coming.”

Dr. Jarstad is looking forward to having voice-activated EMR systems. “In the future we’ll have systems that will let us dictate our findings,” he says. “They’ll be more user-friendly and do more; they’ll make it easier to input data and even code for us.”

In the meantime, Dr. Jarstad still believes using an electronic tablet in the exam room has the potential to work well, no matter what your ophthalmic subspecialty. “I have a colleague who uses a tablet in his oculoplastics practice and swears by it,” he says. “He can draw his findings regarding the eyelids and so forth, and he has templates for each area of concern. He swears by it and won’t use any other system. I also have a retina colleague here at the university who uses it exclusively to make his retina drawings. So I think it can be done; it’s just up to the personal preference of each physician.” REVIEW

Drs. Jarstad and Bashour have no financial ties to any product discussed.