Steroids and Inflammation

As you know, uveitis leads to the accumulation of white blood cells, fibrin and abnormal proteins in the anterior chamber. All of these can block the trabecular meshwork, leading to higher intraocular pressure and glaucoma. However, uveitis is treated with topical steroids that can also increase IOP. So a classic question is: If you're treating uveitis with steroids and the pressure rises, is it the uveitis or the steroids causing the pressure increase? And what's the best way to manage this?

|

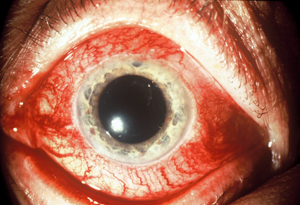

| A red eye accompanying heightened IOP may indicate an arterial-venous fistula. Note the classic "corkscrew" appearance of the blood vessels. |

Often you can't be absolutely certain whether the steroids are the cause, especially if the patient has chronic uveitis and has been on steroids for a long time. But the presence of certain clues may suggest a likely answer. For example, if the patient has new-onset uveitis with a normal IOP and the pressure becomes elevated within a few days of starting the steroids, the steroids are probably not the cause. When intensive, topical steroids cause higher pressures, it usually takes at least one to two weeks; sometimes it takes months.

If the patient starts steroids and the pressure rises in a few days, uveitis may have been partially obstructing the trabecular meshwork and simultaneously reducing the amount of fluid produced by the eye. Those two effects can offset each other, causing the pressure to be normal or even slightly low at first presentation.

In this situation, when steroids are first started they may soothe the eye enough that it begins to make the normal amount of aqueous. This upsets the aqueous balance, and the blockage of the trabecular meshwork then leads to an elevated pressure. But it's not truly a steroid-induced glaucoma; it's more that the steroids have unmasked the uveitic glaucoma. Continued treatment with steroids will eventually reduce the inflammation, allow the trabecular meshwork to rebound and clear itself of debris, and cause the pressure to come down.

Regardless of whether the steroids are responsible for the increase in IOP, the need to treat the inflammation is paramount. If the patient's inflammation is greater than is acceptable to the clinician, more steroids should be used, not less.

Every attempt should be made to control the pressure during this time with medications that are noninflammatory, such as aqueous suppressants; avoid potentially inflammatory medications such as prostaglandins or miotics, and switch to steroids with less of a tendency to increase pressure, such as loteprednol (Lotemax) or rimexolone (Vexol). Sometimes, it's necessary to consider immunomodulatory drugs to control inflammation.

If the pressure remains too high and the inflammation is still unacceptable, use more steroids. If necessary, perform a trabeculectomy or tube shunt.

Red Eye and Elevated IOP

When a patient presents with a red eye and heightened IOP, many clinicians assume the red eye is the result of allergies or a reaction to medication. There's another possibility: The red eye may be a symptom of an arterial-venous fistula, an abnormal communication between arterial and venous vessels. This can cause both the red eye and the heightened IOP.

When abnormal fistulas occur, the venous system around the eye and the orbit can be exposed to the high pressures normally found in the arterial system. This causes the episcleral vessels to become engorged and tortuous. (See image, facing page.) If the pressure backs up into the venous system, it can reduce aqueous outflow, leading to a pressure increase and secondary open-angle glaucoma.

Although this condition isn't common—I only see one case every year or two—it's important to consider the possibility that this is the cause of the glaucoma, for several reasons. First, patients appreciate knowing that their glaucoma has a definite cause; they also need to be educated about the source of the red eye, and the limited options for reducing the redness.

Second, if glaucoma medications don't sufficiently lower the IOP, surgical options like trabeculectomy will have a much higher risk of producing bleeding, including superachoroidal hemorrhage; you should weigh this factor when considering surgery. Third, if you do proceed with surgery, there are steps you'll need to take to reduce the risk of a hemorrhage.

|

| Gonioscopy reveals blood in Schlemm's canal—another symptom of an arterial-venous fistual. |

Finally, if a patient has uncontrollable pressure and other issues such as proptosis, he may require neurosurgical intervention and closure of the abnormal fistula.

A number of clues can alert you to the possibility that the red eye and glaucoma are the result of an abnormal fistula:

• Tortuous veins. In addition to being dilated, the blood vessels on the white of the eye may have multiple kinks and turns—the classic "corkscrew" appearance.

• One-sided glaucoma. Although this problem can affect both eyes, patients with an abnormal fistula often only have abnormally high pressure in one eye only.

• Clues in the history. Risk factors for cavernous fistulas include a history of head trauma, often in an automobile accident. However, it is possible for patients with no previous head trauma—usually middle-aged women

—to develop spontaneous dural cavernous fistulas. These may also spontaneously resolve, in which case the high pressure returns to normal.

• Blood in Schlemm's canal. In some of these patients the backup of blood goes all the way into Schlemm's canal and gonioscopy will reveal a red flush behind the trabecular meshwork. (See picture, left.) However, this effect is not always present, and not always easy to see. A light touch on the gonioprism, ideal viewing conditions and light pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork are needed.

If your index of suspicion is high, an orbital Doppler ultrasound can confirm the diagnosis. This can show the characteristic retrograde flow in the superior ophthalmic vein. (Other tests such as an MRI or CT scanning may reveal an abnormally dilated superior ophthalmic vein, which is not diagnostic but is very suggestive.)

Neurosurgical or interventional radiology treatment can close off the abnormal communication between the blood vessels, but this is accompanied by a significant risk of stroke. So for most patients, if the only symptom is high IOP, it's better to try to control the eye pressure than to consider surgical intervention for the fistula.

Progression with "Acceptable" IOP

Some patients will continue to progress even after IOP has been lowered to what would be an acceptable level for most patients. These patients offer two challenges: not missing the fact that progression is still occurring, and minimizing the likelihood of further progression.

A key strategy to avoid missing progression is to always compare the latest visual field to fields taken several years ago (if available)—not just the previous field. Progression may occur so slowly that if you only compare the two most recent visual fields, differences may appear to be random fluctuations. Significant progression will be much more apparent when comparing fields done over a greater span of time.

If a patient is progressing despite a reasonable IOP, it's possible that the patient's optic nerve is more sensitive to internal pressure than the average eye's. However, I consider several other possible explanations before deciding what steps to take next:

• Pressure fluctuations. First, I check to find out whether the patient's pressure is spiking at other times during the diurnal curve. There's no convenient way to measure the patient's pressure in the middle of the night, but the patient can come in to the office to have his pressure checked at different times during the day. This can be done in a single day or over multiple visits—whatever the patient prefers. Most glaucoma patients progress slowly, so we don't have to gather this information in one week.

• Non-glaucomatous causal factors. Other problems can lead to optic nerve damage, such as a lack of perfusion to the optic nerve at night because of a drop in blood pressure. If an elderly patient who takes multiple blood pressure medications is progressing despite being at your target IOP, it may be worth asking whether he can measure his blood pressure in the evening or at night. Asking about symptoms of postural hypotension may also provide clues.

If a severe drop in blood pressure at night is occurring, the primary care physician may be seeing the patient at a time of day when his blood pressure is at its highest, and consequently prescribing medication that's too strong for other times of day. (Internists are usually receptive to adjusting blood pressure meds.)

Intermittent angle-closure glaucoma can be easy to miss in a young person with little trabecular meshwork pigmentation.

• Lack of compliance. Depending on how you define non-compliance, studies suggest that between 25 and 50 percent of patients don't use their medications as you intended. Some patients may only be at their pressure goal the week before they see you, when they're likely to be most diligent about taking their medications. Unfortunately, poor compliance can be difficult to determine, and there may not be much you can do about it.

As a general rule, if a patient is progressing at a reasonable pressure, it makes sense to lower the pressure further. One option worth considering is laser trabeculoplasty, which may help keep pressure stable even if the patient isn't using his medications optimally. Additionally, outflow-enhancing treatments, both medical and surgical, may be more effective in reducing diurnal pressure variation.

Eye Pain and Headaches

Earlier this year, a woman in her 30s with a three-year history of migraines was sent to me. One eye was densely amblyopic with only count-fingers vision; her other eye had been 20/20 but was now light perception only. She had seen two ophthalmologists and three neurologists because of worsening migraines that were increasingly associated with the vision in her good eye fading out.

When I examined her, her nonamblyopic eye had a pressure of 53 mm Hg; she was in the middle of an intermittent angle closure glaucoma attack, clearly the cause of her migraines and vision fade-outs. No one had realized that this young, hyperopic woman could be having intermittent angle-closure glaucoma attacks because no one had detected the narrow angle.

In retrospect, it's easy to put the puzzle together, but some atypical features made it less obvious for the other clinicians. First, angle-closure glaucoma is much less common in a 30-year-old than in someone in her 60s, 70s or 80s. Second, because the attacks were intermittent, her IOP had always been normal during previous exams. Third, her trabecular meshwork had little pigmentation, making it more difficult to tell whether the angle was occludable.

Unfortunately, people who have intermittent angle closure tend to develop synecheal closure of the angle over time. Eventually a laser iridotomy becomes ineffective because the angle is scarred shut. That was the case with this patient, so I performed a trabeculectomy. She has now gone six months without one of her headaches, which previously occured every day.

Intermittent angle-closure glaucoma is not a common diagnosis, but in recent years I've seen several cases, including two young women. We need to have a low threshold for considering this when patients present with eye pain or headaches. Gonioscopy will reveal the possibility of angle closure, even if IOP is normal.

Dr. Myers is a glaucoma specialist in practice with George Spaeth, MD, and L. Jay Katz, MD, at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia.