Like other patients in need of visual correction these days, many hyperopes are eager to find out what the latest laser and lens technologies can do for them. However, surgeons say they’ve learned from sometimes regrettable experiences to respect the limits of refractive surgery in this cohort of patients.

Nonetheless, by carefully selecting the right candidates and taking advantage of today’s full range of procedures—from PRK to refractive lens exchange—experts say you can meet the needs of more hyperopic patients than ever.

Here, several seasoned surgeons offer advice on choosing the right patients, ruling out inappropriate ones, choosing the best procedures and recognizing risks to avoid.

Choosing the Right Patients

Like most of his colleagues, David R. Hardten, MD, FACS, who is in private practice at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis, rules out more hyperopes than not and chooses ideal candidates based on age. “Compared to 10 or 15 years ago, we just don’t do as much laser vision correction for higher levels of hyperopia,” he says. “The optical quality that corneal refractive surgery provides to these patients isn’t as good as we can achieve now with refractive lens exchange because of the availability of today’s high quality IOL implants.”

Naturally, most of his hyperopic patients are presbyopic, and are starting to explore their options for refractive correction. “At that point, you really should be thinking about what will satisfy your patient five, 10 and 15 years down the line,” he says. “That’s why RLE procedures represent the vast majority of surgeries I perform on hyperopes.”

However, Dr. Hardten says he will still occasionally perform refractive surgery on younger hyperopes who have significant astigmatism. “If you have a patient who is +0.5 D with

+2 D astigmatism, you can relieve their astigmatism with a corneal procedure and leave them a little bit hyperopic. They end up being pretty happy—until they become presbyopic in their mid 40s.” He recommends against plano corrections. “Usually, a little bit of hyperopia is going to be better because their accommodative tone tolerates this mild hyperopia and they won’t be happy with plano or even a

-1 D or -0.5 D correction. As they get older and their refractive tone

relaxes, you find yourself chasing their changing refractive errors. That’s the challenge of correcting younger hyperopes—and why it’s better to wait until you can do the lens replacement.”

|

For Scott MacRae, MD, director of refractive services in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Rochester, the ideal hyperope for a corneal refractive procedure is 45 to 55 years old, with a correction that ranges from +1 D to +3 D. “The critical thing is for them to be stable,” he says. “I find that these patients do very well with LASIK. Once they get into the 60s, though, they start getting cataracts, and that changes everything.” Hyperopes in their 50s or 60s with a refractive error of +4 D or greater are typically what Dr. MacRae considers good candidates for RLE. “However, for any patient in that age group with a progressive, developing cataract, I defer the refractive surgery until they’ve had their cataract surgery. After cataract surgery, you can fine-tune their refraction with LASIK or PRK.”

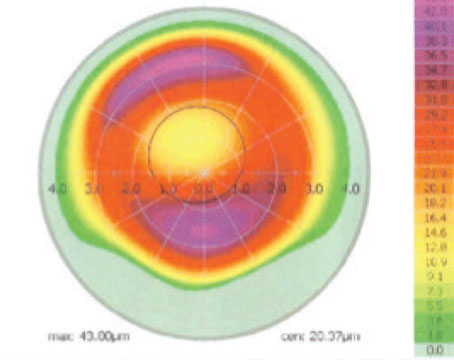

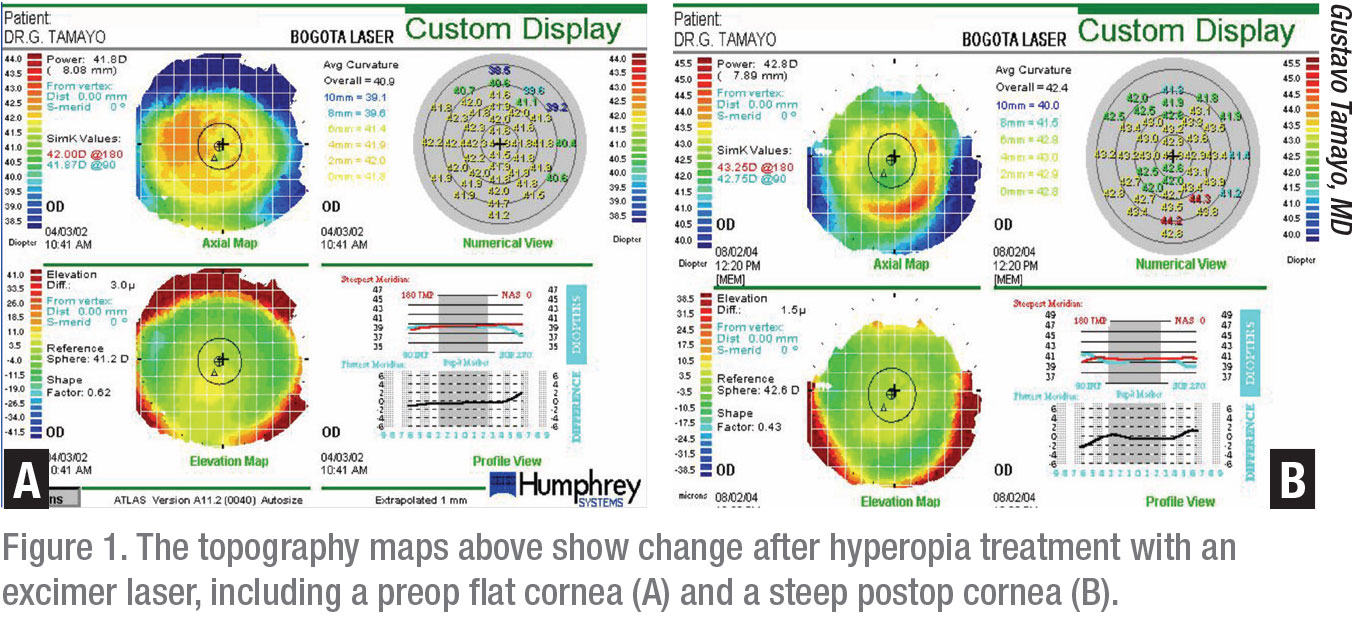

Gustavo Tamayo, MD, director of the Bogota Laser Ocular Surgery Center in Bogota, Colombia, is an exception to the general rule, making generous allowances for high correction of hyperopes, as long as their keratometry readings don’t exceed 49 D. “At 49 D or below, I believe you can effectively correct up to +6 D of hyperopia,” he says.

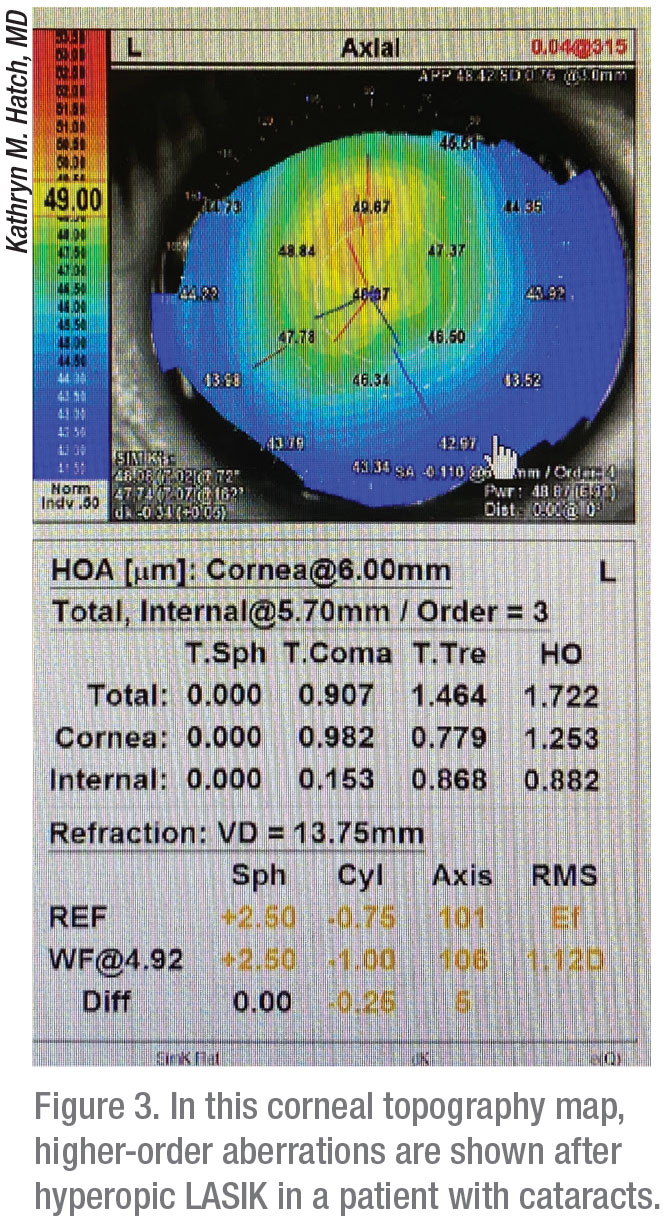

Kathryn M. Hatch, MD, director of the refractive surgery service at Massachusetts Eye & Ear and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, points out that hyperopic laser vision correction isn’t always a predictable treatment, especially at higher corrections. This can make patient selection a less-than-exact science. “Low hyperopia and mixed astigmatism patients do fairly well,” she notes. “Patients under +2 D or +3 D typically do well.”

Patients to Rule Out

Unlike Dr. Tamayo, Dr. MacRae says steep corneas typically put hyeropic refractive surgery prospects on the do-not-operate side of his appointment book. “If their corneas are at 47 D or 48 D, I avoid doing the surgery, especially in a +3 D correction and especially in smaller eyes, because I’m at risk of creating a curvature of more than than 50 D. The patient will likely experience regression.”

|

Dr. MacRae also rules out patients still undergoing refractive changes. “Another red flag goes up for me when patients want near corneal refractive procedures, especially if they’ve never done monovision,” he says. “These patients are probably better off with a trifocal IOL or a mix-and-match biofocal IOL and expanded-depth-of-focus IOL. But it’s critical that they have reasonable expectations before you offer them premium IOLs.”

He also puts the brakes on refractive surgery when patients have a significant and ongoing shift in hyperopia. “A lot of times that’s an indicator that they’ll have an early cataract,” he says. “I will defer these patients. The second type of patients that I observe more carefully are the younger ones. For example, for people in their early 40s, the manifest refraction may be +1.5 D. Then, when we do their cycloplegic refractions, it might be +2.5 D or +2.75 D. That tells me their hyperopia is latent and that it can get worse over the next few years. You probably want to defer those patients for 18 months to see how they’re progressing.” When the patients become less latent and more definitively hyperopic, Dr. MacRae says they’ll emerge as stronger surgical candidates. “If you treat them before this point, they’ll drift after treatment,” he adds.

Dr. Hardten avoids patients with refractive errors above the +3 D to +4 D range or—in the under-35 set—even above the +2.5 D to +3 D range. “You can create a lot of optical aberrations when you perform corneal refractive surgery on these patients, so I’d be outside of the range in which I’d offer surgery,” he says. “Because a 25-or-30-year-old isn’t presbyopic, if you perform an RLE, you’ll produce artificial pseudo-accommodation, like you would with a presbyopic IOL, but you’ll also get glare and halos.”

Once you start using a corneal procedure to correct more than +3 D or +4 D, treatments become extremely unpredictable, according to Dr. Hatch. “Patients end up wearing glasses because they regress,” she adds. “So I won’t do them.”

Although Dr. Tamayo’s upper limit of acceptable correction (+6 D) is much higher than what the other surgeons interviewed for this article accept, he’s conservative when considering a patient’s ocular surface. “We have to remember that we’re significantly increasing the curvature of the eye and therefore significantly increasing the dryness of the eye because of less-efficient coverage,” he notes. “With a more prominent cornea, in terms of how well it’s covered by the curvature of the lid, if the patient has dry eye, that could exclude him from refractive surgery.”

The typical shallowness of the anterior chamber in hyperopes is another concern. “With some exceptions, many of these patients have an eye that’s too shallow or an anterior segment that’s too crowded for a phakic IOL,” says Dr. Hardten. “They really don’t do well with laser vision correction, in my opinion, and they’re too young for RLE.”

Which Procedures Are Best?

When considering the limited number of good candidates for hyperopic corneal refractive correction, Dr. Hardten says LASIK, SMILE and even PRK are all reasonable choices under the right circumstances. “With LASIK and SMILE, you have a faster recovery, of course, plus the lack of an epithelial defect. However, one of the challenges with LASIK and SMILE for hyperopic patients is that you tend to have larger optical zones and the eyes are smaller. You will have limited room to make a flap for LASIK or a tunnel or interface for SMILE.”

|

He notes that this predicament is even greater in hyperopic astigmatic patients. “Their eyes are shorter in the vertical direction and wider in the horizontal direction, potentially keeping you from blending those ablations way out to the periphery. So, as a result, I find that I provide a higher percentage of PRK procedures to these patients than I do to my standard myopic patients. Your ability to create the optical properties that you want is probably increased with PRK.”

Drs. Tamayo, Hatch and MacRae believe that LASIK is the treatment of choice for hyperopes, with some exceptions.

If the patient’s cornea is thin or irregular, Dr. Tamayo uses LASEK, which replicates the treatment of PRK once he creates a defect in the epithelium, instead of in the stromal tissue. “I use SMILE for myopic procedures, but more work is needed to develop an accurate nomogram for SMILE if we’re to use it well in hyperopic refractive surgery,” he adds.

Dr. Hatch is also looking forward to using SMILE. “Right now, though, I won’t use SMILE on hyperopes because it hasn’t been approved for this use by the FDA,” she adds.

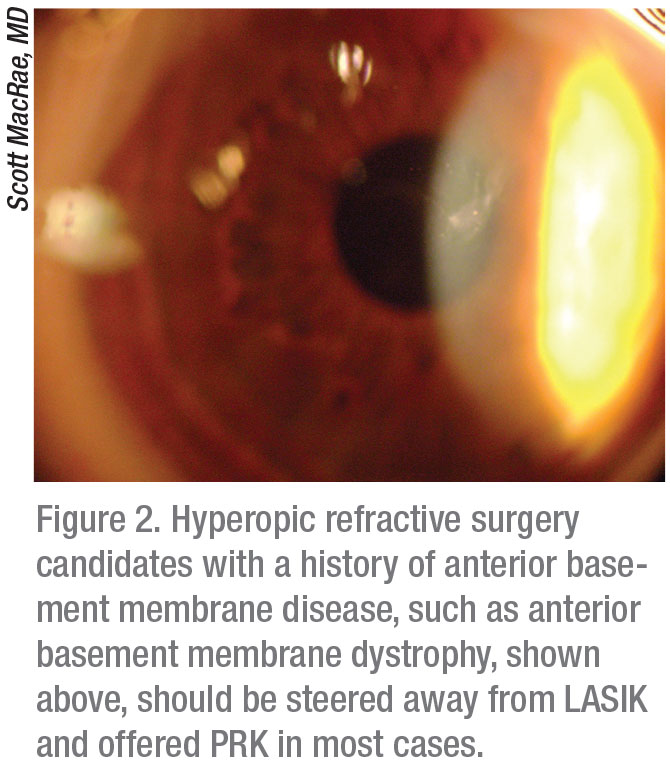

Dr. MacRae says most hyperopes do well with LASIK, except those with a history of anterior basement membrane disease (such as anterior basement membrane dystrophy), which is sometimes found after RK. “These patients tend to do better with PRK,” he notes. Also, for older hyperopes who’re undergoing corneal refractive procedures, Dr. MacRae recommends “pampering” their epithelium because it tends to be looser. “I’ve found over the years you may need to stretch the LASIK flap to get it into place for these patients, following up with a bandage lens,” he says.

Remember These Risks

Dr. Hardten urges his colleagues to keep in mind that hyperopic refractive surgery patients in general have a greater risk of experiencing optical aberrations, such as glare and halos. “Because, as I mentioned, the flap goes farther into the periphery, these patients actually also have a higher risk of epithelial ingrowth with LASIK and also with SMILE,” he observes. “And then, on the PRK side, remember that you’re doing a larger-diameter ablation and will probably see slower epithelial recovery than you would in postop myopes.”

Although Dr. Hardten typically won’t rule out a patient because of ocular surface disease, he encourages preventive and therapeutic vigilance against all conditions that fall under this large umbrella when you perform LASIK, SMILE or PRK. “It’s very important to maximize management, using all of the many treatments that are available,” he says.

Echoing Dr. Hatch’s concern, Dr. MacRae prepares for unpredictable results in hyperopic refractive surgery. “I may have a retreatment rate of less than 5 percent for myopia but it’s probably more like 10 percent for hyperopia, and some of that is related to hyperopic shift,” he says. “You’ll tend to spend less time on the lower hyperopes, but in the higher hyperopes, it’s harder to hit the target, because I think the epithelium is trying to fill in and neutralize some of the higher correction. I tell the higher hyperopes they’re more likely to need retreatment.”

Dr. Hatch says the biggest risks she encounters are undercorrection and regression. “You may find the need to enhance your patients a few years down the line,” she adds. “Other complications, such as dry eye, high aberrations, glare and difficulty driving at night, also develop in high corrections,” she adds.

|

Best All-Around Strategy

All of these surgeons agree that close communication with your patients is the best all-around strategy for achieving success when using refractive procedures to manage hyperopia.

“It’s a challenge,” Dr. Hardten says. “You’re taking them somewhere they’ve never been before and they’re very excited. But most of the time, they start thinking unrealistically, that they will end up just like their friend who doesn’t wear glasses. You need to tell them this is different. You need to describe something that is impossible to describe and that each patient experiences in a unique fashion.

“After each procedure, pay attention to how well you’ve understood that unique patient’s personality and what the patient had wanted out of the surgery,” he continues. “Also, how well the patient understood what you could have reasonably delivered, and if you helped the patient recognize the shortfalls of the technology, as well as the advantages of being less spectacle-dependent. Bringing these patients through this experience while making as few of them unhappy as possible is your best measurement of success.” REVIEW

Dr. Hatch is a consultant with Zeiss and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Drs. Tamayo and Hardten are consultants with Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. MacRae reports no financial relationships with relevant companies.

1. Choul YP, Sei YO, Roy SC. Measurement of Angle Kappa and Centration in Refractive Surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 23:4:269-75, 2012.