In a glaucomatous eye, a disc hemorrhage is a sign of trouble, indicating that the disease is active and progression is likely. Unfortunately, disc hemorrhages are difficult to spot during an exam, and none of today's computerized imaging devices can reveal them. Nevertheless, it's possible to become better at finding them—and doing so may benefit your glaucoma patients significantly.

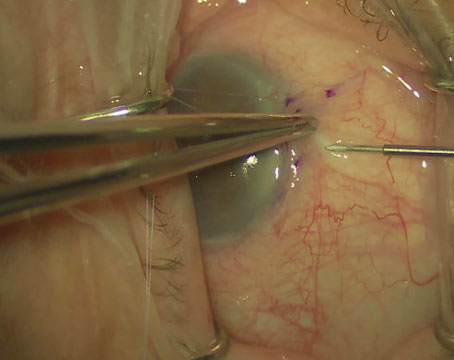

Disc hemorrhages usually occur at the border of the optic disc in the neurofiber layer, although they may also occur inside or just outside the disc edge. They're sometimes called splinter hemorrhages, because they look like splinters running parallel to the nerve fibers in the nerve fiber layer, or Drance hemorrhages, after Steven Drance, MD, who did much of the seminal work that first established the connection between these hemorrhages and glaucoma progression.

Although disc hemorrhages are not unique to glaucoma—differential diagnoses include vitreous detachment and small vascular accidents such as those that may occur in diabetic or hypertensive patients—in patients with known glaucoma, disc hemorrhages may indicate disease progression. A large number of studies suggest that a patient with glaucoma and a hemorrhage has a high likelihood of progression.1-3 Furthermore, some of our own recent work suggests that if a patient has a hemorrhage, it's highly likely that visual field progression was occurring before its onset.4

A disc hemorrhage, of course, is a sign of damage rather than something we need to attempt to treat; it will usually go away by itself within four months. So it's a question of treating the patient, not the hemorrhage.

The Glaucoma Connection

Despite the association between disc hemorrhages and glaucoma, it's not clear exactly how many individuals with glaucoma have them.

Different studies have come to different conclusions looking at different populations. In the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial, about half of the subjects had a hemorrhage at some point, although that may only reflect that particular category of glaucoma. By way of comparison, some large population-based studies have found disc hemorrhages in only 0.1 to 0.2 percent of normals.

|

In any case, disc hemorrhages are seen in all types of glaucoma, from ocular hypertension to advanced primary open-angle glaucoma and from low-tension to high-pressure glaucomas. The association with progression seems to be similar in different glaucomas as well; for example, the hazard ratio for future progression was very similar in the Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study and the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study.

The literature does suggest that disc hemorrhages may be slightly more common in low-tension glaucoma patients, but there's no really solid data to support that conclusion. The greater frequency with which disc hemorrhages are noted in normal-tension patients could simply be an artifact—the result of ophthalmologists paying closer attention to the optic disc in this group of patients. (Disc hemorrhages are easy to miss if you're not specifically looking for them.) Of course, it is possible that disc hemorrhages really are more common in low-tension glaucoma patients; if so, it may be the result of some process intrinsic to the normal-tension glaucoma patient. At this point, we can't say for sure.

Which Comes First?

Although a link between glaucoma and disc hemorrhage clearly exists, the nature of that link is still subject to debate. One possibility is the vascular theory: The blood vessel breaks first, leading to subsequent damage and progression. Some individuals may be prone to blood vessels breaking as the result of an inherent process, or something related to the vascular system that makes them more susceptible to this type of damage.

The second possibility is the mechanical theory, which hypothesizes that the primary event is neurodegeneration of the optic nerve because of glaucoma; the tissue is collapsing, which puts stress on the blood vessel, eventually leading to bleeding.

Right now, the evidence regarding which scenario is correct is not definitive, and there's room for discussion on both sides. But we've noted, and other people have found, that disc hemorrhages usually occur at the edge of an existing defect in the retinal nerve fiber layer, or at a notch in the rim.5 That suggests that there's already damage present at that location; i.e., the glaucoma is progressing and the hemorrhage follows. In addition, the areas that develop disc hemorrhages are often associated with pre-existing visual field defects. That's another piece of evidence that the glaucomatous damage precedes the appearance of the hemorrhage.

Improving Your Spotting Skills

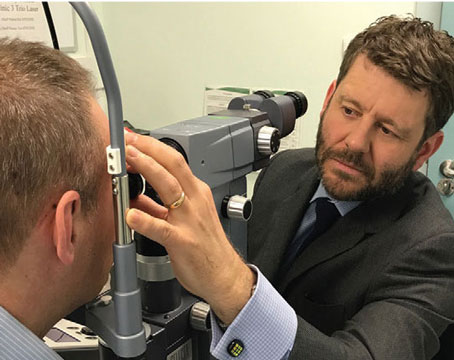

Unfortunately, disc hemorrhages are very easy to miss during an exam. None of the currently available imaging devices is able to reveal the presence of a disc hemorrhage, and few ophthalmologists dilate every glaucoma patient at every visit. Likewise, few ophthalmologists take a photograph at every exam—but if you really want to find disc hemorrhages, that may be necessary. In the OHTS study, for example, four times as many disc hemorrhages were found on photographs as were found during standard disc examinations.6

|

The method we use to improve our skills is to periodically dilate our glaucoma patients (as clinically indicated) and take a photograph. We then study the photograph while the patient is present, looking for disc hemorrhages that we missed during the exam—and we often find one. When we do, we go back and examine the eye again, to see the hemorrhage directly and gain a better understanding of why we missed it. Over time, this has helped us refine our ability to spot hemorrhages. Furthermore, we find that we can spot them through smaller and smaller pupils. (Of course, we still miss some—but we catch far more than we used to.)

It does help to know where to look. Often, disc hemorrhages occur adjacent to areas of previous damage, such as in an area of parapapillary atrophy, retinal nerve fiber layer defect or rim notch, so it makes sense to focus your attention there. However, they sometimes appear in completely different locations. Usually we focus on the temporal half of the disc; two-thirds of disc hemorrhages occur inferotemporally.

How It Changes My Treatment

If I do find a disc hemorrhage, I consider it a sign that the status of the patient may be more serious than previously believed. How this would change my approach to a given patient depends on the patient's status.

First, if the patient is a glaucoma suspect, the appearance of a disc hemorrhage suggests to me that the individual does indeed have glaucoma. I would change my diagnosis accordingly—unless there was an additional symptom such as a vitreous detachment. In theory, two disease processes could be present, but the likelihood of that is low; so if I find a disc hemorrhage in a glaucoma suspect, that's sufficient cause for me to change the diagnosis to glaucoma.

Second, I might alter treatment, depending on my discussion with the patient. For example, if the patient is already on one medication, I might add a second. I might perform a laser trabeculoplasty, depending on the individual's pressure range. However, I wouldn't perform invasive surgery on a patient based solely on the presence of a disc hemorrhage. The risk profile for surgery is very high, and not every disc hemorrhage leads to progression of field loss. I prefer to find some sort of functional correlate before I expose the patient to that risk.

Third, I'd change my level of surveillance. A disc hemorrhage tells me that the patient is at high risk of progression. Instead of having him come back in a year for a visual field, I might have him come back in four or six months for another field test and another look at the optic nerve.

Despite the correlation between disc hemorrhages and progression of visual field loss, it's difficult to predict whether a given patient with a hemorrhage will progress. If a patient has been actively progressing over the past two years and you find a disc hemorrhage, you can probably assume the patient is going to continue to progress. But the reality is that some patients with a disc hemorrhage won't have any obvious visual field progression afterwards, even though we suspect they're being damaged in an ongoing way. That's why deciding how to respond is a risk-stratification issue.

At the least, if someone has a hemorrhage you should follow him more carefully. You may find a hemorrhage but see no progression even a year later; this may indicate that there's not enough damage to lead to field loss, or that the progression is happening extremely slowly. Surgery doesn't usually make sense in this situation, and the patient would probably agree. But if you find that his field loss has progressed three months later, you know he has a functional correlate. In that situation, surgery may be warranted.

Making the Effort

The presence of a hemorrhage tells us that the disease is active. That's why it's so important to examine the disc carefully and look for hemorrhages at every visit, even when the patient isn't dilated. And, if possible, it's worth making the effort to train yourself to be better at spotting disc hemorrhages, perhaps using an approach like ours. When you do take a photograph, check it immediately for disc hemorrhages; if you find one, re-examine the patient to see why you missed it.

Finally, when you do find a disc hemorrhage, do two things: First, change your surveillance, recognizing that the patient is at risk. Second, consider advancing therapy for that patient. A hemorrhage likely indicates that the disease is active, and you need to respond accordingly.

Dr. Liebmann is clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York University School of Medicine, adjunct professor of clinical ophthalmology at New York Medical College in Valhalla, N.Y., and director of glaucoma services at Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital and New York University Medical Center.

1. Drance SM, Fairclough M, Butler DM, Kottler MS. The importance of disc hemorrhage in the prognosis of chronic open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95:226-228.

2. Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1965-1972.

3. Prata TS, De Moraes CG, Teng CC, Tello C, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Factors affecting rates of visual field progression in glaucoma patients with optic disc hemorrhage. Ophthalmology 2010;11:24-9.

4. De Moraes CG, Prata TS, Liebmann CA, Tello C, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Spatially consistent, localized visual field loss before and after disc hemorrhage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:4727-33

5. Law SK, Choe R, Caprioli J. Optic disk characteristics before the occurrence of disk hemorrhage in glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:411-413.

6. Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Feuer WJ, et al. Detection and prognostic significance of optic disc hemorrhages during the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2006;113:

2137-2143.