Right now, there’s a revolution taking place in glaucoma surgery centered around minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, or MIGS. The overarching theme behind MIGS is safety, but as the popularity of MIGS increases, efficacy and cost effectiveness are also becoming an issue. Here, we’d like to provide an update on the MIGS procedure known as gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, or GATT. GATT shows promise in all three areas—safety, efficacy and cost effectiveness.

The History of Trabeculotomy

The idea that a trabeculotomy might cause a drop in IOP first came to the fore back in the 1950s, when Morgan Grant, MD, hypothesized that 75 percent of resistance to aqueous outflow was inherent in the trabecular meshwork—and that it could be eliminated by creating an opening between the anterior chamber and Schlemm’s canal.1 Many years later, working with more sophisticated technology, David Epstein, MD, redid those studies and found that the resistance produced by the trabecular meshwork was actually somewhere in the 60-percent range.2 Despite the difference in the numbers, the conclusion was clear: The majority of resistance to aqueous outflow in POAG is caused by the trabecular meshwork. (This is often true in the secondary glaucomas as well.)

Using a trabeculotomy to restore flow through the patient’s natural drainage system was a great idea; previous surgical alternatives involved creating an entirely different outflow pathway via options such as trabeculectomy or a tube shunt. (Those options don’t involve the patient’s natural drainage system at all. Moreover, shunting aqueous away from the natural drain may further contribute to the eye’s impaired outflow capacity.)

One of the pioneers of this type of approach was Redmond Smith, MD, who published his initial description of the ab externo technique of trabeculotomy using a nylon filament in 1969.3 Initially, his version of the procedure generated a lot of interest because it showed great promise as a means to lower intraocular pressure, especially in primary congenital and juvenile open-angle glaucoma. The idea that a trabeculotomy could potentially eliminate 75 percent of the outflow resistance was very appealing, so many surgeons were eager to try this in their POAG patients. However, his approach had several drawbacks and limitations that caused it to eventually drop in popularity:

• It takes a long time to do. Even in the best hands, this procedure takes 30 to 60 minutes or longer.

• It violates the conjunctiva. Performing a trabeculotomy ab externo requires a large conjunctival dissection, a large scleral flap and several scleral sutures. Surgeons didn’t want to violate the superior conjunctiva and the sclera because it would make any subsequent surgery less likely to be effective.

• The pressure drop wasn’t as great as that obtained with a trabeculectomy or tube shunt. Especially when trabeculectomy was performed with mitomycin-C, it produced a more significant pressure drop than ab externo trabeculotomy.

|

Ironically, we now know part of the reason for this: Many surgeons performed ab externo trabeculotomy using metal trabeculotomes to open the canal. Because of the limitations associated with this approach, they were only opening the superior nasal and temporal parts of the meshwork. Anatomic studies have revealed that most of the outflow in the eye occurs inferonasally.4 So, not only was a significant amount of the trabecular meshwork not being opened, the sections that were being opened weren’t as effective for drainage.

The impact of this on the effectiveness of the procedure was supported by a study published in 2012, in which eyes treated with a 360-degree trabeculotomy created with a nylon suture under a scleral flap (25 eyes with POAG and 18 eyes with secondary open-angle glaucoma) were compared retrospectively with 16 POAG and 19 SOAG eyes treated with metal trabeculotomes.5 At 12 months, the POAG patients’ success rate was 84 percent using the sutures vs. 31 percent using the trabeculotome; it was 89 percent vs. 50 percent in the SOAG group. This demonstrates the comparative power of opening up 360 degrees of the trabecular meshwork rather than, say, 120 to 180 degrees. The more of the angle you open, the greater the pressure decrease you get. (We see this same trend in the other MIGS surgeries currently available.)

Trabeculotomy: Previous Data

Before we discuss the details of performing the GATT procedure, let’s review what some of the previously published data says about the effectiveness of trabeculotomy.

• A 2004 Japanese retrospective review included 149 eyes with primary congenital and juvenile open-angle glaucoma that received 360-degree ab externo trabeculotomy.6 The patients were followed for 9.5 ±7.1 years; the data showed a success rate of nearly 90 percent at final follow-up. Mean IOP at that point was 15.6 ±5.0 mmHg.

This supports the idea that circumferential 360-degree trabeculotomy is the gold standard for treating developmental glaucoma. We almost never see success rates in the 90-percent range with any glaucoma surgery, but we’re seeing that with trabeculotomy in kids who have this type of glaucoma.

• Another Japanese study, published in 1993, looked at using ab externo 360-degree trabeculotomy in patients with open-angle glaucoma, POAG and pseudoexfoliation.7 Depending on which type of glaucoma the patient had, the threeand four-year success rates ranged from 60 to 70 percent. That’s equivalent to the success rates found in the five-year Tube vs. Trab study.8 So there’s significant longterm data showing that this type of surgery is equivalent to what major prospective studies have found with trabeculectomy and tube shunts.

|

| A GATT procedure is performed. 1) Gonioscopic view showing the blunted prolene suture in the AC, filled with healon GV. A 25-ga. MVR blade has created a goniotomy. The back wall of Schlemm’s canal (a white strip by the tip of the blade) is visible. 2) A blunted 5-0 prolene suture is used to cannulate Schlemm’s canal. The tip is in the canal, confirmed by direct visualization. 3) The blue color of the prolene con- firms placement of the suture through the entire canal. 4) The distal end of the prolene suture has circumnavigated the canal 360 degrees, and the tip is retrieved with microsurgical forceps. 5) Traction is placed on the proximal end of the suture. |

|

| 6 & 7) A complete 360-degree circumferential trabeculotomy is completed. 8) One can begin to see blood reflux into the anterior chamber. 9) With aggressive irrigation, balanced salt solution is used to lavage the downstream collector channels. A nearly 360-degree episcleral venous fluid wave confirms the patency of the downstream collector channels. |

• Another retrospective, multicenter study published in 2011 evaluated the surgical outcomes of trabeculotomy in 121 eyes that had steroid-induced glaucoma, comparing their outcomes to those in 108 eyes with POAG that underwent trabeculotomy and 42 steroid-induced glaucoma patients who underwent trabeculectomy.9 At three years, trabeculotomy was significantly more effective at treating steroid-induced glaucoma than it was at treating POAG. However, the two surgeries were not significantly different when it came to treating steroid-induced glaucoma. This data suggests that, for treating this type of glaucoma, trabeculotomy is just as effective as trabeculectomy.

The Advantages of GATT

Over time, variations on the trabeculotomy procedure were developed. Then, about seven years ago, Dr. Fellman came up with the idea for GATT. As already noted, earlier methods for performing trabeculotomies were ab externo, requiring the creation of a scleral flap, with all of the associated problems. Some recent versions also used a catheter, which has a few drawbacks as well. The ab interno GATT procedure has eliminated many of those drawbacks while maintaining the advantages and remarkably good success rate that a complete, 360-degree trabeculotomy has to offer.

To perform a GATT, we begin by making a goniotomy in the nasal quadrant. We then cannulate the canal with a 5-0 prolene suture that’s been blunted using low-temperature cautery, which allows it to go around the angle more easily. We pass the suture through the canal 360 degrees, retrieve the end and then pull the loop into the anterior chamber. (See example, above.) The result is that we’ve treated 360 degrees of the angle with just two small paracenteses. This leaves a trabecular shelf.

Typically, our postoperative regimen is primarily concerned with keeping any inflammation under control. Patients are on steroids and antibiotics four to six times a day for the first week. If we see a steroid response and the IOP is 17 mmHg or higher, we’ll add pilocarpine at night plus a beta-blocker; if it’s 22 mmHg or above, we’ll have the patient use pilocarpine twice a day throughout the follow-up period. At one week we stop the antibiotics but keep the patient on steroids until the eye is quiet; then we taper the steroids.

Sometimes we’ll keep our patients on Pred Forte once a day, and possibly pilocarpine at night, for three to six months, just to theoretically inhibit any potential wound healing in the angle. (The goal of the surgery is not to get the patient off all drops; the goal is to decrease dependence on medications and lower the pressure.) We also have the patient follow hyphema precautions—primarily keeping the head of the bed elevated—until the hyphema is gone.

The advantages GATT include:

• It’s much safer and less invasive than ab externo trabeculotomy; it only requires making two small paracenteses.

• It restores flow through the eye’s natural drainage system.

• It takes much less time to perform than ab externo trabeculotomy.

• It doesn’t violate the conjunctiva, so it doesn’t limit future surgical options.

• It’s cost effective and can be performed with a $4 suture (5-0 prolene).

• It’s very safe, with few complications. Those that do occur tend to be self-limiting with minimal consequences.

• Our data indicate that it’s very effective. (More on that below.)

In terms of limitations, it’s still true that a procedure such as a trabeculectomy might achieve a very low IOP such as 10 mmHg, which isn’t likely to be achieved with a GATT. However, one reason that MIGS procedures have become popular is that surgeons have realized that not every patient requires a pressure that low.

What Our Data Show

In recent years we’ve conducted several studies to determine how effective the GATT procedure is when treating different types of glaucoma. The results indicate that it can be very effective, although its effectiveness varies with the type of glaucoma and its severity.

• In 2014 we published a study involving 85 eyes of 85 patients; 57 had POAG and 28 had secondary open-angle glaucoma.10 Both POAG and SOAG patients showed a significant and sustained drop in pressure and a significant, sustained decrease in dependence on drops. At 12 months the POAG patients had an average IOP decrease of 11.1 mmHg (SD=6.1), with a reduction in medications of 1.1. The secondaryglaucoma group showed an IOP decrease of 19.9 mmHg (SD=10.2), with 1.9 fewer medications being used. Eight of the 85 patients (9 percent) were considered to have failed because they needed further glaucoma surgery.

• In 2015 we published a study examining the effectiveness of this surgery on children who had a dysgenic anterior segment angle and uncontrolled primary congenital glaucoma or juvenile open-angle glaucoma.11 This was a retrospective chart review; patients ranged in age from 17 months to 30 years old. Fourteen eyes of 10 patients underwent GATT. We found that mean IOP decreased from 27.3 to 14.8 mmHg—a tremendous drop— and mean medication use decreased from 2.6 to 0.86 drops. This supports our belief that this technique (either ab interno or ab externo) is an excellent primary surgery for these types of glaucoma.

| Pearls for First-timers | ||

|

• In 2017 we published a study regarding the use of GATT in 35 eyes of 35 patients with prior incisional glaucoma surgery (mean age: 67.7 years; mean follow-up time: 22.7 months).12 Nineteen eyes had a prior trabeculectomy; 13 had a prior glaucoma drainage device; four had a prior Trabectome; and five had prior endocyclophotocoagulation. Overall, IOP dropped from 25.7 mmHg to 15.4 mmHg; medication use dropped from 3.2 meds to 2 meds (p<0.001). Traditional thinking has been that patients with a previous trabeculectomy or tube shunt would have a somewhat degraded natural drainage system, potentially minimizing the effectiveness of a trabeculotomy. However, the data for each group in this study showed that all patients benefited from the GATT surgery. Despite the fact that these patients had a prior failed trabeculectomy or tube, we were able to re-establish flow through their own drainage system. Overall, at 24 months, in this refractory glaucoma group, about 60 percent of patients did well. (Keep in mind that these patients would be considered high-risk; they’d already undergone failed prior incisional surgery.) At 24 months only about 30 percent of eyes required further incisional surgery. Looking at the groups separately revealed that the prior-tube group did a little better with a GATT than the prior-trabeculectomy group. But even in the prior-trabeculectomy group, we were able to re-establish flow in a significant number of patients.

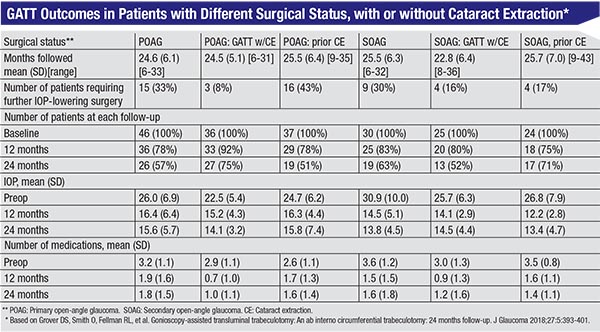

• In 2018 we published a report summarizing the two-year data from the original cohort of patients we treated when first developing the GATT technique.13 The data included 198 eyes of 198 patients with no prior incisional surgery; all of them had open-angle glaucoma with a mean pressure ≥18 mmHg. We divided the patients into categories based on their type of glaucoma and situation relative to cataract surgery, as follows: patients with POAG; those who had phaco at the same time as GATT; pseudophakic patients; secondary open-angle glaucoma patients; SOAG patients who had phaco and GATT at the same time; and pseudophakic SOAG patients. (See table, page 43.)

Findings included:

— POAG patients overall had a mean decrease of 9.2 mmHg (37.3 percent), with a decrease of 1.43 medications.

— SOAG patients overall had an average decrease of 14.1 mmHg (49.8 percent), with a decrease of two medications.

— The cumulative proportion of failure at two years ranged from 0.18 to 0.48, depending on the group.

In terms of complications, the vast majority of these patients had a hyphema, most of which resolved at one week. None of these patients developed any significant or harmful complications. There was one case of choroidal detachment, and there were a handful of other isolated complications, but all were minimal and self-limited, and they resolved quickly. In terms of safety, this procedure is head and shoulders above trabeculectomies and tubes.

Choosing the Right Patients

There’s a very important point to note here: It’s crucial to pay attention to the status and condition of the individuals participating in any study—particularly in terms of how sick the eyes are. This is especially true when the study concerns a MIGS procedure. For example, the COMPASS trial, iStent studies and Hydrus study were all done on patients with a Humphrey visual field mean deviation of 0 to -5 or so. In other words, the eyes being studied were fairly healthy.

In contrast, consider the eyes in the last study discussed above. They had pressures in the upper 20s on two to three medications, with mean deviations ranging from -6.5 to -11.8. In other words, the impressive results we obtained were in patients with advanced disease that could potentially blind them if not treated appropriately. This suggests that, unlike many MIGS procedures, GATT may be appropriate even in some eyes that have advanced disease.

It’s also important to consider how different subgroups within a study responded to treatment. For whatever reason, the subgroup of patients who were pseudophakic in this study tended to do significantly worse than the other subgroups. Forty-three percent of them—almost half—were counted as failures because they needed further glaucoma surgery. At the same time, the data make it clear that the SOAG patients tended to do better. That makes sense, because most of the time their problems are associated with the trabecular meshwork, so removing the trabecular meshwork works well for them. Overall, the POAG groups did pretty well; at 24 months the cumulative proportion of failure was anywhere from 10 to 30 percent. The subgroup that did the best was the patients who received GATT at the same time as cataract surgery.

The exception among the POAG patients was the pseudophakic group; they tended to be older, with a worse mean deviation, and they tended to do worse after GATT. About 40 percent of the pseudophakic POAG patients needed further surgery at 24 months. GATT did lower their pressure; it just wasn’t sufficient for this group of patients, who needed an IOP in the low teens.

The data also made it clear that patients with the most serious disease are unlikely to get enough help from an angle procedure. Our criteria for failure was very similar to the Tube vs. Trab study, and at six months, almost 90 percent of POAG patients with a mean deviation of -15 dB or worse failed. (Notably, this paper was one of the first to demonstrate a correlation between phase of disease and outcome.) These patients should not have an angle surgery—including GATT. They have resistance to outflow at multiple layers, not just at the trabecular meshwork. To prevent further damage, they need a pressure of 11 or 12 mmHg—the kind of pressures you may only achieve with a trabeculectomy, tube shunt or possibly a XEN45 implant, for example. They need more relief than any angle surgery will be able to give them. They need a new drain.

This was an important realization for us. When we first came up with the GATT procedure, we thought it was the best thing since sliced bread; we were doing it in everybody. Now we realize that as effective as GATT is, it’s not going to be sufficient to rescue some patients. Knowing this is allowing us to tailor the surgery to the patient based on the stage of disease.

Despite this caveat, we believe the GATT procedure produces pretty impressive results. Of the original cohort—with the exception of the pseudophakic POAG patients—70 to 90 percent did not need a new trabeculectomy or tube after GATT. That’s pretty powerful. In fact, in our clinical practice the GATT procedure has significantly decreased the number of patients that need a trabeculectomy or tube.

Strategies for Success

When performing GATT, these strategies will help ensure a good outcome:

• If the patient has a significant layered hyphema postoperatively, consider washing it out. Everyone has a different preference when it comes to something like this, but we believe that blood in the eye after surgery is a bad thing, so we’re pretty aggressive. If the patient has a significant layered hyphema at the one-week point, we have a low threshold for washing it out.

• Patients with newly diagnosed severe glaucoma may do better with GATT. This is because years of drops can have a deleterious effect on the eye. In the United States, patients with very advanced glaucoma have usually been on drops for 10 or 20 years. In those rare cases in which an eye is newly diagnosed with advanced glaucoma, however, the eyes tend to do better with angle surgery.

This is relevant because as previously noted, patients in the United States with a mean deviation of worse than -15 tend to do poorly with GATT. However, I’ve also done this surgery in developing countries. As the visiting doctor from America, I’m usually given the most advanced cases. Notably, however, these eyes have not been subjected to years of drops and preservatives. I was shocked to discover that despite their advanced disease, these virgin eyes did very well with GATT—much better than U.S. eyes that are in similar condition, but with years of exposure to eye drops.

We’re still researching this, but I think it’s going to have tremendous implications for our work in developing countries. In the meantime, it’s challenged my understanding of glaucoma drops and lowered my threshold for doing nonmedical treatments for glaucoma, be it selective laser trabeculoplasty or a MIGS procedure.

• Advise patients who like to sleep on their side to sleep on the same side as the surgery. As already noted, the vast majority of outflow is in the nasal quadrant. If a patient lays straight back with the head elevated, the blood will settle down. However, if the patient is going to rest on one side or the other, we want her to turn toward the side of the surgery so that the blood pools temporally, not nasally. For example, if we perform GATT on the left eye, the patient should lean to the left. If the patient rests on the right side, the blood will pool nasally in the operated eye, in the part of the angle that’s responsible for the greatest outflow.

This advice is the opposite of what the patient will expect, so it’s important to mention it.

• Do the surgery with the patient in reverse Trendelenberg position. We do this with all of our patients, no matter what the surgery is—cataract surgery, tube shunts or angle surgery. Getting the head above the heart minimizes episcleral venous pressure and minimizes blood reflux. We believe this increases the safety of the surgery while helping to maintain visibility. (Of course, as with every anterior segment surgery, you must maintain the anterior chamber at all times to avoid complications.)

• Base the direction of your approach on the eye you’re treating (i.e., left or right). In right eyes, we insert the suture going counterclockwise; in left eyes, we insert it going clockwise. The reason is that you’re going to get the most resistance after the suture has been passed about 260 degrees into the canal. Using this approach, if the suture stops at 260 degrees, it will be at the 6 o’clock position; then you can go to the top of the bed and do a cut-down, or just pull on the suture. But if you start from the opposite side and the suture stops at 270 degrees, it will stop at the 12 o’clock position. You’re not going to be able to access it without lying on top of the patient.

• Leave some Healon in the eye, based on the amount of blood reflux and/or the episcleral venous fluid wave. On the first day postop, patients will have a relatively low pressure because they still have glaucoma medications in their systems—aqueous suppressants, prostaglandin analogues and so forth. Until those medications are washed out, IOP may be lower than normal, and if the pressure’s too low postoperatively the patient can have blood reflux. Ideally the pressure should be about 15 to 17 mmHg on the first day; you don’t want a pressure of 5 or 6 mmHg at that point.

To help ensure that the pressure doesn’t drop too low, we leave a little bit of Healon in the eye. How much we leave in the eye depends on how much blood reflux we see, and/or the episcleral venous wave we see. If we see a huge wave and a lot of blood reflux, we may leave 40 percent of the Healon in the eye. If we see a minimal wave, we may leave 5, 10 or 20 percent in the eye.

• Use a suture, not a catheter. Using a suture is, in some ways, better than using a catheter. For example, if the suture stops, you can pull on it; it tears through the trabecular meshwork and treats the vast majority of the angle. If the catheter stops at 200 degrees and you pull on it, it just comes out.

Another reason to use a suture is cost: A GATT can be done using a $4 suture, whereas a catheter may cost $750. That’s very significant for both the patient and the health-care system, in both the United States and worldwide.

What’s Next?

GATT is a novel, safe, minimally invasive, conjunctiva-sparing surgery that comes with a lot of pre-existing data because it’s a modification of a surgery that’s been around for 60 years. Its mid-term success is similar to previously published results for ab externo trabeculotomy (the primary exception being POAG patients who need to end up with a pressure of 10 or 12 mmHg), but with far fewer issues of safety and complications. We believe it’s unquestionably a surgery of choice for some types of glaucoma, such as uncontrolled primary congenital glaucoma or juvenile open-angle glaucoma, and it does very well treating secondary open-angle glaucomas where the primary problem lies in the trabecular meshwork.

GATT also promises to help our patients and the field of health care by keeping costs down. The fact that a GATT can be done using a $4 suture rather than a $750 catheter is important. The reality is, we’re going to increasingly be held accountable for the choices we make, not only in terms of outcomes, but also in terms of cost. A relatively inexpensive and very effective procedure has tremendous implications for health care in general and the field of glaucoma surgery in particular.

Currently, we’re organizing a prospective GATT study, with the intention of generating data with a longer follow-up period.

Neither Dr. Grover nor Dr. Fellman has any financial interests relevant to the subjects discussed in this article.

1. Grant W. Further studies on facility of flow through the trabecular meshwork. Arch of Ophthalmology 1958;60:523-33.

2. Rosenquist R, Epstein D, Melamed S, Johnson M, Grant WM. Outflow resistance of enucleated human eyes at two different perfusion pressures and different extents of trabeculotomy. Current Eye Research 1989;8:1233-1240.

3. Smith R. Nylon filament trabeculotomy. Comparison with the results of conventional drainage operations in glaucoma simplex. Trans Ophthalmol Soc N Z. 1969;21:15-26.

4. Dvorak-Theobald G. Further studies on the canal of Schlemm: its anastomoses and anatomic relations. Am J Ophthalmol 1955; 39:65–89.

5. Chin S, Nitta T, Shinmei Y, Aoyagi M, Nitta A, Ohno S, Ishida S, Yoshida K. Reduction of intraocular pressure using a modified 360-degree suture trabeculotomy technique in primary and secondary open-angle glaucoma: A pilot study. J Glaucoma 2012; 21:6:401-7.

6. Ikeda H, Ishigooka H, Muto T, Tanihara H, Nagata M. Long-term outcome of trabeculotomy for the treatment of developmental glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:8:1122-8.

7. Tanihara H, Negi A, et al. Surgical effects of trabeculotomy ab externo on adult eyes with primary open angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111: 12:1653-61.

8. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL; Tube versus Trabeculectomy Study Group. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153:5:789-803. e2.

9. Iwao K, Inatani M, Tanihara H; Japanese Steroid-Induced Glaucoma Multicenter Study Group. Success rates of trabeculotomy for steroid-induced glaucoma: A comparative, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:6:1047-1056.

10. Grover DS, Godfrey DG, et al. Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, ab interno trabeculotomy: Technique report and preliminary results. Ophthalmology 2014;121:4:85561.

11. Grover DS, Smith O, Fellman RL, et al. Gonioscopy assisted transluminal trabeculotomy: An ab interno circumferential trabeculotomy for the treatment of primary congenital glaucoma and juvenile open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:8:1092-6.

12. Grover DS, Godfrey DG, Smith O, Shi W, Feuer WJ, Fellman RL. Outcomes of gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT) in eyes with prior incisional glaucoma surgery. J Glaucoma 2017;26:1:41-45.

13. Grover DS, Smith O, Fellman RL, et al. Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy: An ab interno circumferential trabeculotomy: 24 months follow-up. J Glaucoma. 2018;27:5:393-401.