Every ophthalmologist treating glaucoma knows that patients have problems with compliance and adherence, and it’s no secret that a lot of this is tied to the cost of treatment. In one study of patient/doctor communication over a series of glaucoma visits, a patient said (on camera), “Sometimes I forget [to buy the drops] purposely, because they’re so darned expensive. I figure if I use them half as much, I’ll only pay half the money.”1

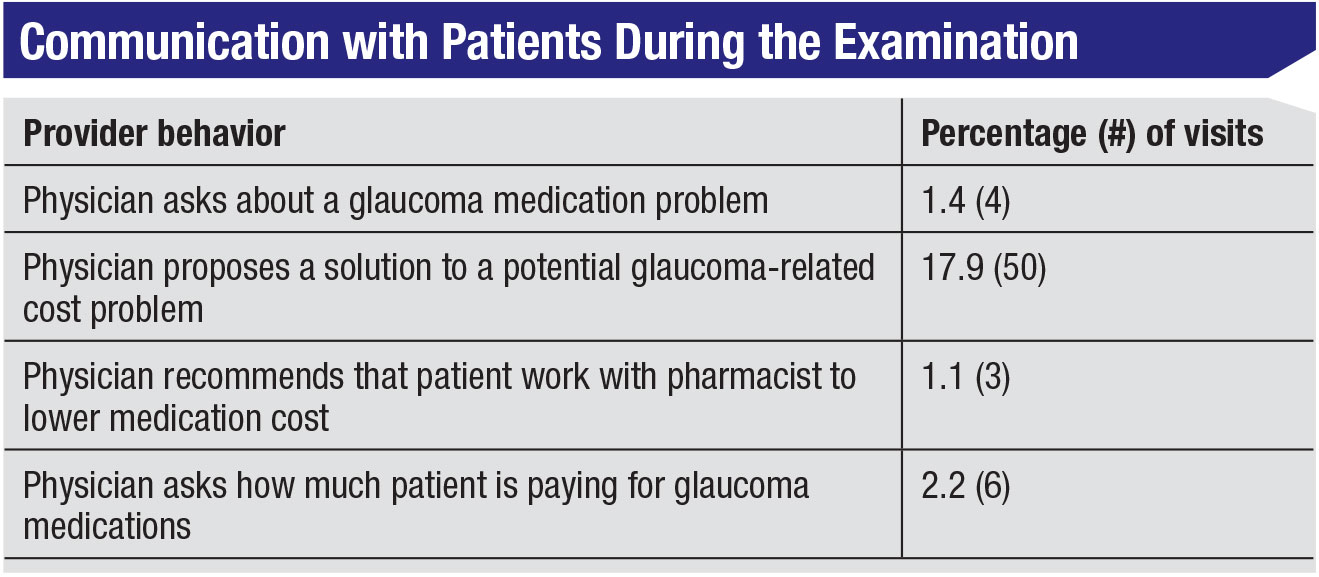

There are actually a number of ways to reduce the cost of the medications patients have to purchase, but this fact is rarely discussed when patients are in the clinic. In fact, the same study of patient-physician communication found that medication costs were only discussed in 1.4 percent of visits(!) (See Table, facing page.) Another study involving asthma patients found that 40 to 50 percent of patients wanted to discuss medication cost with the doctor, but the patients only brought it up in a tiny fraction of the visits.2

Here, I’ll share nine ways you can help your patients reduce the costs associated with glaucoma treatment.

1. Talk to your patients about cost and availability concerns.

As noted above, most patients aren’t going to bring up their cost concerns, so you, the physician, should bring up the topic. You might say: “Glaucoma is a life-long disease, but we’ll work together to create a treatment plan that’s sustainable over the long term. Do you have any difficulty paying for your glaucoma medications?” That can open the door to a longer discussion.

|

Also, in some cases the drug you’re prescribing may not be part of the patient’s insurance company’s formulary. Be sure to address that by advising the patient on the best way to proceed.

2. Consider switching the class of medication you’re prescribing.

Joshua Stein, MD, and his group did a worldwide price com-parison of glaucoma medications, as well as laser trabeculoplasty and trabeculectomy.3 The price differences among the drug options are significant. (See chart, page 62.) As you’d expect, beta blockers are the least expensive, at about 38 cents a day; the price jumps up significantly when you move to combination products. Not surprisingly, the newest medications are the most expensive.

It’s worth explaining to the patient the difference between brand name drops and generics, and why the generics are usually—though not always—less expensive (e.g., not having to repeat the animal and human clinical studies of safety and effectiveness that were required of the brand-name drug, and marketplace competition driving down the cost). It’s important to emphasize, however, that the patient should always check the prices to make sure the generic is actually less expensive; factors such as shortages can alter prices.

You should also point out that the generic may not be identical to the brand name drug, since only the active ingredient has to be the same. For that reason, you should advise your patient to let you know in the unlikely case that any problem with side effects arises.

3. Spell out options in your prescription.

The key here is to allow the patient access to the least expensive form of the prescribed drug (when appropriate). When writing the prescription, consider prescribing generics, or write “generic substitution OK” as a note to the pharmacy. Also, purchasing the components of combination medications separately may be less expensive for the patient. Writing “OK to dispense separate components if costs less” may help remind the patient to ask about this. (You should point out to the patient that this will eliminate some of the convenience of a combination drop, especially since it’s important to wait five or 10 minutes between drops to avoid washing out the first drop with the second.)

|

4. Encourage the patient to shop for the lowest price.

Patients may not realize that medication prices can vary widely from pharmacy to pharmacy, and even from day to day. There are a number of strategies that can help your patient find the best price on glaucoma drugs:

— Generics are sometimes less expensive at large chain stores. For example, as I write this it’s possible to purchase a 30-day supply of some generics for as little as $4 at Target and Walgreen’s. However, availability may change from year to year. For example, Walmart used to offer timolol for $4, but it’s no longer on their list.

— Buying a larger supply often lowers the per-day price. For example, a 90-day supply may be less-expensive per day than a 30-day supply. (Of course, this requires a larger initial outlay, but with an inexpensive generic that may not be a significant issue for most patients. For example, generic timolol might cost $4 per month, vs. $10 for a three-month supply.) One important caveat: Don’t suggest buying a larger supply to save money until your drug regimen for the patient has been settled.

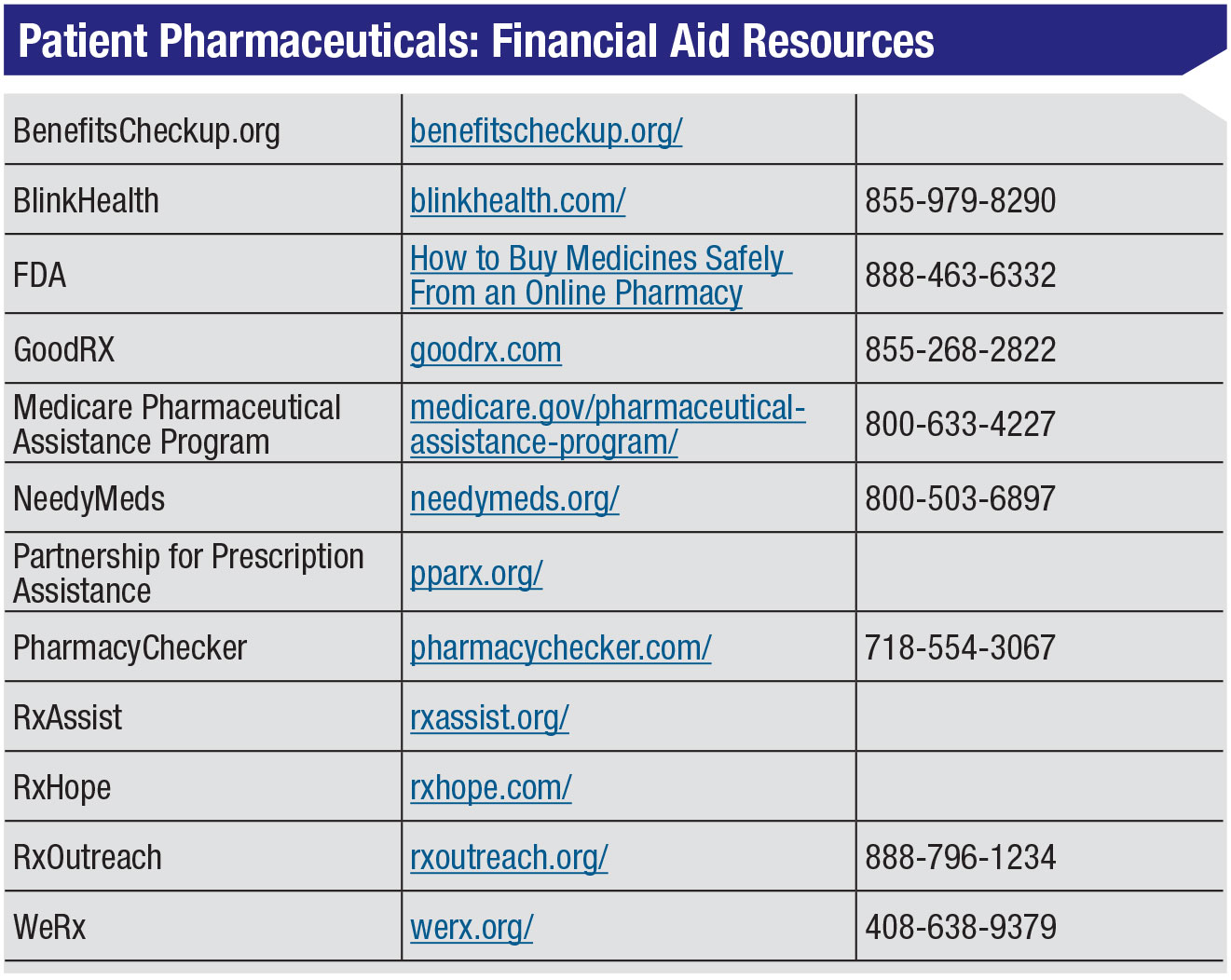

— Patients can compare prices by calling their local pharmacies, or by doing a little research online. Some websites and apps compare local prices for you, although they may not include every local source. One well-known option is GoodRx.com, which lists local prices, sometimes offering a free coupon that can be printed out or sent to the patient’s phone. GoodRx claims that this can result in cost savings up to 80 percent. (I called the local pharmacies in a listing to see if the listed prices were correct; they were not always accurate to the penny, but they were very close.) The drawback of GoodRx.com is that is doesn’t include prices from local independent pharmacies. Often, independent pharmacies will have pretty good deals, especially for cash-paying patients.

Additional online resources include BlinkHealth, WeRx.org, SlashRx and several others.

— The type of pharmacy your patient buys from can make a difference. Independent pharmacies may offer lower prices on brand-name products, and sometimes will offer a discount if the patient pays cash. On the other hand, for generics, the lowest prices may be at the large chains such as Target and Walgreen’s. Some pharmacies also offer prescription savings clubs you can join, although patients already on Medicare or Medicaid probably won’t qualify.

— The drug manufacturer may offer coupons, especially for newer drugs. These may be a mixed blessing, however, as the manufacturer may find other ways to retake some of the discount by raising the co-pay or changing coverage limits. Also, this type of coupon may not be available to patients already on Medicare or Medicaid.

5. Be willing to provide a written prescription.

Although most of us today simply send an electronic prescription to the patient’s pharmacy, some patients who are interested in shopping around for the best price may need a written prescription so they have something to fax (or scan) to show to the pharmacy.

-(1).jpg) |

6. Warn patients to be careful about buying drops online.

Even some sources that have been “vetted” by supposedly reliable organizations like PharmacyChecker.com and the Canadian International Pharmacy Association (CIPA) have been charged with misrepresenting the source of the drugs they sell. If your patients want to pursue this, they should visit fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm048396.htm for advice from the federal government on how to ensure they’re purchasing their drugs from a reliable source.

7. Encourage your patient to talk to the pharmacist.

In the past, pharmacists were prohibited by law from discussing price options with patients. That “gag order” has now been lifted—although it’s still in place until 2020 for patients on Medicare and Medicaid.

This is important, because the lowest price, even in one pharmacy, is not always the one patients expect. For example, the cash price of a drug may actually be lower than the co-pay charged by the insurance company—meaning the patient would shell out less when buying the drug with cash than by using his or her insurance. (This is often the result of having a “pharmacy benefits manager” at the insurance company who negotiates co-pays and other details with the pharmacy.) Most patients wouldn’t expect the cash price to be cheaper, so they pay the co-pay without questioning whether this is actually the best deal.

Here’s a hypothetical example: Suppose the benefits manager has negotiated a $15 co-pay for a supply of a generic drug. The medicine in question cost the pharmacy $2.05. If the patient pays the $15 co-pay, the pharmacy might be reimbursed $7.22 by the insurance company, resulting in a profit of $5.17 for the pharmacy. The pharmacy benefits manager claims the remaining $7.78.

In contrast, the price for a cash sale is set by the pharmacy. Since the drug cost them $2.05, they could double that to make a profit, and the patient paying cash would be charged $4.10. That’s a lot less than $15. Even if the pharmacy quadruples the cost to make a more substantial profit, the patient would pay $8.20, still substantially less than the $15 co-pay.

How widespread is the phenomenon of patients paying more than necessary for their drugs? A 2018 study conducted by Dana Goldman, PhD, and colleagues looked at this question using Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data from 9.5 million prescriptions purchased in 2013.4 They found that 23 percent of the time, patients would have been better off paying cash. The average overpayment isn’t huge ($7.69), but that adds up over time.

Other findings from that study included that overpayment was more likely to occur with a generic than with a brand name. (This makes sense, given the lower price of most generic drugs.) However, the average size of the overpayment was smaller when generics were purchased. The total overpayments for drugs in their data sample totaled $135 million for the year 2013.

8. Encourage your patient to take advantage of patient assistance programs.

There are many programs designed to help patients afford their drug prescriptions. Some are national, some are state-sponsored and some are regional or local.

There are a number of nationwide nonprofit organizations, such as NeedyMeds, Partnership for Prescription Assistance, RxAssist, RxHope and RxOutreach. For some patients, including those for whom English is a second language, the paperwork involved in taking advantage of these resources can be a challenge. RxHope might be a good option for those patients, as it will help those patients complete the paperwork. NeedyMeds also provides a list of programs that are able to help patients with the paperwork.

|

Many drug manufacturers also have patient-assistance programs. I called up one drug manufacturer to see how this works. It became clear that they don’t provide patient advocates to help patients navigate this process, but the customer service representative I spoke to was pretty helpful.

More information about what the drug companies have to offer can be found online at medicare.gov/pharmaceutical-assistance-program/. Another strategy is to simply call the drug manufacturer and ask about drug cost assistance, or Google the name of the manufacturer along with “patient assistance program.”

A particularly helpful resource for your patients is benefitscheckup.org, which is sponsored by the National Council on Aging. I like this resource because it summarizes all kinds of benefits that are available for your patients, including benefits related to health care in general, income assistance, food and nutrition, housing and utilities, tax relief, benefits for veterans and employment assistance. It asks for some basic demographic information, such as age bracket and income level; then it tells you what kind of benefits you can apply for. Of course, it’s up to the patients to take advantage of the programs for which they qualify.

9. Consider performing SLT. We’ve already seen evidence that selective laser trabeculoplasty is an effective first-line treatment.5 It’s also less expensive for the patient in most cases; the worldwide price comparison of glaucoma medications mentioned earlier3 found that bilateral laser trabeculoplasty is less ex-pensive than a three-year supply of latanoprost in 71 percent of developing countries—including the United States. Despite this data, old habits die hard. Most physicians, especially in the United States, still start with medications first.

Recently, new evidence was published that suggests that SLT can be as effective—or more effective—than starting treatment with medications.6 This data came from a multicenter trial looking at patients with POAG and ocular hypertension that was conducted in the United Kingdom. In this trial, 356 subjects were randomized to laser, 362 to eye drops. The primary outcome was quality of life, and surprisingly, they didn’t find any statistically significant difference between the groups. (You might have expected that patients would have complained about their eye drops, compared to a single laser treatment.) However, this was confounded by the fact that patients had individual target IOPs, so even if you had the laser, you might end up back on a drop if you didn’t quite reach the target. Furthermore, the quality-of-life in-struments used may not have been sensitive enough to detect treatment side effects related to this.

Nevertheless, at 36 months, 74 per-cent of the SLT group didn’t require drops to maintain target IOP, and over the three-year period of the study, there was a 97-percent probability that SLT as first treatment was more cost-effective than starting with eye drops. Furthermore, eyes of patients in the SLT group were at the target IOP at more visits than patients in the eye-drop group (93 percent vs. 91.3 percent of visits); and no one in the SLT group required glaucoma surgery to lower IOP, while 11 patients in the eye-drop group did. This is pretty compelling data.

Passing It On

Of course, sharing all of this with patients during an examination might take more time than a physician is able to spend. An alternative would be to make up a sheet summarizing all of the cost-saving suggestions that are relevant, including whatever helpful organizations are based in your state and local area. Another possibility would be to provide patients with a copy of an article I wrote for the Brightfocus Foundation, which was written for patients rather than physicians, that summarizes this in-formation. (You can find the article at brightfocus.org/glaucoma/article/top-10-tips-reducing-costs-your-glaucoma-medications.)

Given that the ongoing cost of glaucoma treatment can be a challenge for many of your patients, they’ll be grateful for your help. REVIEW

Dr. Ou is an associate professor of ophthalmology, co-director of the glaucoma service

and vice chair for postgraduate education in the Department of Ophthalmology at the UCSF School of Medicine in San Francisco.

1. Slota C et al. Patient-physician communication on medication cost during glaucoma visits. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94:1095-1101.

2. Patel MR, Wheeler JR. Physician-patient communication on cost and affordability in asthma care. Who wants to talk about it and who is actually doing it. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:10:1538-44.

3. Zhao PY, Rahmathullah R, Stagg BC, et al. A worldwide price comparison of glaucoma medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy surgery. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:11:1271-1279.

4. Van Nuys K, Joyce G, Ribero R, Goldman DP. Frequency and magnitude of co-payments exceeding prescription drug costs. JAMA 2018;319:10:1045-1047.

5. Waisbourd M, Katz LJ. Selective laser trabeculoplasty as a first-line therapy: A review. Can J Ophthalmol 2014;49:6:519-22.

6. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:10180:1505-1516.