Physicians say that diagnosing a dry-eye patient, especially one who’s seen several doctors already without getting any relief, is akin to trying to have a conversation in the middle of noisy, crowded room. To make any sense of things, you’ve got to be able to cut through the noise of the patient’s varied, and sometimes conflicting, signs and symptoms and focus on certain key elements. In this article, cornea experts describe how you can get to the root of the problem when faced with a suspected dry-eye patient.

Stop, Look and Listen

Experts say you can learn a lot about a patient both by asking the right questions and by paying careful attention to his eyes as you speak with him.

“The clinical exam starts when they come in the door,” says Bennie Jeng, MD, Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “I watch them as we chat; I want to see their blink rate and the position of their lids. Many patients come in and say, ‘I’ve been diagnosed with dry eye,’ but as I watch them I notice they instead show signs of lower-lid ptosis, have incomplete blinks, or are older and pre-Parkinson’s and don’t blink. Their problem isn’t really dry eye, it’s exposure. You can give this type of patient artificial tears every hour and it’s not going to solve their exposure problem.”

|

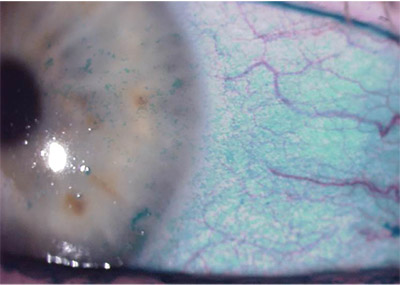

| Moderately severe dry eye with diffuse staining of conjunctival and corneal epithelium with lissamine green. Photo courtesy of Terrence P. O’Brien, MD |

Deepinder Dhaliwal, MD, director of refractive surgery and the Cornea Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh, also watches patients’ blinking and behavior. “I look at how much they’re touching their eyes,” she says. “A lot of people with chronic irritation will try to pick mucus out of their eyes, or just keep touching them, and cause mucus fishing syndrome.” In mucus fishing syndrome, touching the conjunctiva to remove mucus irritates the conjunctiva, which then produces more mucus. The patient then touches it again to remove the new mucus, perpetuating the cycle.

Dr. Dhaliwal also says if you don’t take control of the exam from the beginning, you risk being drawn into a 45-minute, meandering discussion. Don’t let the patient come in and immediately dictate that the diagnosis is dry eye, even if he’s seen other doctors already. “I’ve found that the most effective thing I can do is ask, ‘What are the top three things that bother you about your eyes?’” she says. “If you instead start with an open-ended question such as, ‘Tell me more about your dry eyes,’ the patient will launch into a litany of complaints and such, which takes a lot of time and often doesn’t work well with clinic flow and scheduling. After asking the topthree question, patients’ responses can be fascinating. You’d think the typical dry-eye patient would say that his eyes burn or hurt—but no. Sometimes they’ll talk about their ‘decreased vision.’ This isn’t just fluctuating vision, which I’d expect with dry eye, but actual decreased vision, which they blame on their dry eye. In one patient, this decreased vision wasn’t dry eye—it was a cataract. I’ve had another patient say the number-one problem was itching that he said was from his ‘dry eye.’ But itching isn’t dry eye, it’s allergy. So, unless you ask the question and the patient answers in his own words, you don’t know what you’re dealing with.

“The other benefit of them stating these top three issues is that you then have very clear goals,” Dr. Dhaliwal continues. “If they say their eyes burn, then your goal is to decrease that. If it’s fluctuating vision, then we know we have to deal with that.”

Dr. Jeng says the timing of the patient’s symptoms is also a clue. “If it’s truly dry eye, it tends to get worse as the day goes on,” he says. “If, instead, they say the problem starts first thing in the morning, then there are one or two issues at work: One, it’s not dry eye; and, two, it’s probably due to exposure during the night, because if their eyes are closed during the night, they shouldn’t be drying out.”

Physicians say it’s also important to find out what medications the patient is taking, since many systemic medications, such as anti-depressants and anti-histamines, can impact the ocular surface. Something as simple as getting the patient off of an oral allergy drug and treating the problem locally can make a difference.

Exam Tips

Experts say the exam is especially important in possible dry-eye patients, because of the relationship, or lack thereof, between signs and symptoms in the disease.

| |

| If you’re looking to add some data points to your dry-eye exam, you might give these tests a look: • Advanced Tear Diagnostics TearScan. This system tests a tear sample for the level of the protein lactoferrin, which appears to be associated with dry eye. In the 510(k) approval study, the sensitivity of the test was 83 percent (severe dry-eye cohort), and the specificity was 99 percent (normal cohort). • Bausch + Lomb Sjö Test. The company says this blood test may help physicians detect Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with dry-eye complaints. It tests for four traditional biomarkers and three novel ones, B + L says. • Johnson & Johnson Vision/TearScience LipiView II/LipiScan. The LipiView II system images the meibomian glands, visualizes and measures the thickness of the lipid layer and helps detect partial blinks. LipiScan is a smaller unit that just provides the gland imaging. • Oculus Keratograph 5M. This is a combination corneal topographer, keratometer and color camera. Oculus says it can help image the meibomian glands and tear breakup time, measure the tear meniscus height and let you evaluate the lipid layer. • Quidel InflammaDry. This is a rapid, qualitative test for the presence of the inflam- matory biomarker metalloproteinase-9 in tears. The company says this can help give you some idea of the role of inflammation in the dry-eye complaint. • TearLab Osmolarity Test. Tests for the level of osmolarity in the tears of a suspected dry-eye patient. Readings above a certain level, either from one eye or in terms of the difference between the eyes, are deemed abnormal and might indicate an issue with the ocular surface’s health. |

“There is a disconnect between signs and symptoms,” explains Terrence P. O’Brien, MD, professor and Charlotte Breyer Rodgers Distinguished Chair in Ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute of the Palm Beaches in Florida. “Most dry-eye patients complain of irritation, such as dryness, foreign body sensation and burning, but fluctuation in vision—especially with the excess screen time seen in younger patients—can be one of the early symptoms that’s overlooked. Paradoxically, however, some patients with moderate to severe disease may have very few symptoms, while others will have disabling symptoms.”

Dr. Jeng describes his approach to the physical examination: “I look at the lid position, blink rate and the completeness of blinks,” he says. “I check for lagophthalmos by having them lie back and pretend to go to sleep, but tell them not to squeeze their eyes and instead just relax. I look to see if there’s any exposure as they close their eyes. As part of this, I’ll ask if anyone sees them while they’re asleep, and often, they’ll say their spouse sees them. I’ll follow-up by asking the spouse (if present) if the patient sleeps with their eyes partially open, or I’ll ask the patient if anyone’s ever told them they sleep like this. If they tell me that they’ve always slept with their eyes partially open, and they say their symptoms are bad right from the get-go in the morning, that’s a clue that it’s an exposure issue.”

To help cut through the confusion of patients’ complaints, during the exam Dr. Dhaliwal will instill a drop of artificial tears without telling the patient the nature of the drop, and ask if it relieves the pain/discomfort/burning, etc., for even five seconds. “If it’s a true dry-eye patient, it will help for at least five seconds,” she says. “If they say no, then I’ll instill a drop of proparacaine—without telling them what it is—and ask how their pain is. If that doesn’t relieve it, then I know I can’t help them either; helping the ocular surface won’t help this deep, neuropathic pain.”

In her exam, Dr. Dhaliwal pulls down the patient’s lower lids and has him look up, then pulls up the upper lids and has him look down. He then looks left and right. “Look to see how floppy their lids are,” she advises. “Look for areas of hyperemia or superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis.”

During the exam, physicians will assess the meibomian glands in order to gauge their effect on the patient’s complaints. After various testing (see below), Dr. Dhaliwal will use a Q-tip to push on the glands and evaluate the secretions. She also examines the base of the lashes to check for Demodex and/ or to categorize any blepharitis.

Helpful Tests and Stains

Most physicians rely on their exam and the patient’s symptoms when diagnosing dry eye, but note there are some tests that provide useful insights.

Though it can take a relatively long time and isn’t too popular with patients, some physicians will administer a Schirmer’s I test (without anesthesia). “If the result is low—between a zero and a 2—one knows that there truly is aqueous deficiency,” says Dr. O’Brien. Dr. Dhaliwal, in an effort to gauge patients’ tearing but avoid some of the issues with Schirmer’s testing, prefers to use a phenol red thread, or zone quick, test in patients with a very low tear lake. “You put in the phenol red thread and assess the amount of tear production over 15 seconds,” she explains.

“It’s easier than Schirmer’s and patients don’t complain too much about it.”

Some clinicians use a few newer, point-of-care tests to garner more data. “I’ve found tear osmolarity testing helpful, but I don’t use it in every patient,” says Christopher Rapuano, MD, chief of Wills Eye Hospital’s Cornea Service. “I use it in the patients in whom I’m suspicious of a dry-eye issue or in whom there’s something unusual that doesn’t quite fit.” He says a high osmolarity can be a vote to continue with treatment, but a low result might incite him to look for something else, such as conjunctivochalasis.

Dr. O’Brien will also sometimes administer the InflammaDry test for the inflammatory marker metalloproteinase-9. “This is a biomarker of inflammation,” he explains. “It’s not perfect—it’s semi-quantitative, not 100-percent quantitative—but it can help us confirm the presence of ocular inflammation and can be helpful when monitoring the effect of chronic immunomodulatory therapy. With positive results, the patient can be informed, ‘Your tears show inflammation,’ in order to reinforce the necessity for chronic use of various anti-inflammatory medications.”

Dr. Rapuano has the original LipiView device. “LipiView I images the tear lipid layer, which we have found helpful in determining partial blinkers, but not that helpful in determining MGD,” he says. “We don’t have LipiView II, which does do meibomian gland imaging. I do think there’s good rationale for imaging the glands for treatment and diagnosis, and for showing patients that they have gland dropout.”

Whatever ancillary tests are used, the physicians note that tear-film breakup time and staining are cornerstones of the diagnosis. Dr. Jeng says it’s important to remember that, although staining is important, not all staining equals dry eyes. “One of the common things we see is diffuse corneal staining in patients who’ve been told that they have dry eye and, as a result, have tried many different treatments,” he says. “However, this turns out to be toxicity from too many drops. It doesn’t mean they didn’t start out with dry eye, just that now they’re overmedicated. Treating these patients is a challenge because the treatment is to take away medicines, while we’re trained to give them to patients.”

Dr. Jeng identifies some other staining patterns and what they might indicate: “Superior corneal staining is not dry eye,” he emphasizes. “Swirling staining indicates limbal stem cell deficiency issues. Inferior conjunctival staining only—without cornea staining—can be a sign of mucus fishing syndrome.

“Dry-eye staining is usually in the inferior third or half of the cornea,” Dr. Jeng continues, “along with staining of the inferior limbus and inferior and lateral conjunctiva.”

Another step in determining that aqueous deficiency is present involves examining the tear lake. “Make sure that it’s the appropriate size/volume,” Dr. Jeng says. “If they don’t have an adequate tear lake, it could be aqueous deficiency.” If practices are soequipped, they can also use anterior segment OCT to measure tear parameters. “This is a quantitative way of looking at the tear meniscus dimensions to assess tear volume, and provides very useful information in select patients,” says Dr. O’Brien.

In the end, Dr. Dhaliwal says that listening to the patient’s main complaints, regardless of what previous physicians have told them, and doing your own exam will cut through the noise. “With some patients,” she says, “you have to untangle the mess—but do it efficiently.” REVIEW

Dr. Rapuano consults for TearLab. Drs. Dhaliwal, Jeng and O’Brien have no relevant financial interests to dryeye diagnostic devices or tests.