Screening and management of refractive surgery patients calls for increasingly accurate use of the corneal topographer and a better understanding of the resulting data. Maps produced by the topographers have advanced in precision and detail over the past 20 years, and even now some manufacturers are developing modifications to get a better look at the corneal surface. In this article, two leading refractive surgeons present guidelines for the ophthalmic technician capturing images with the corneal topographer and for the ophthalmologist reading and interpreting the maps.

Taking good pictures with the corneal topographer is the ophthalmic technician's contribution to successful management of a refractive surgery patient. As in other diagnostic procedures, a review and an update of the patient's medical history is a necessary first step. In addition to the usual questions about past eye surgery, injury or corneal disease, Brazilian refractive surgeon Wallace Chamon suggests asking the patient if he has been using any eyedrops, especially lubricants. Dr. Chamon explains that viscous lubricants like gels can interfere with corneal topography. "Also look if the patient's eye has been dilated," he cautions, "because the brightness of the instrument can cause some glare and make it difficult for the patient to look at the target," interfering with the procedure and resulting in poor mapping.

|

| The AstraMax's polar grid uses advanced surface reconstruction algorithms. |

Positioning the Patient

When you're lining things up on the topographer, the head position should always be so that it exposes as much of the eye as possible, in-structs Dr. Holladay. "So, for people who have a great big brow, you might want to tilt their chin forward and head back," he advises. "Don't be afraid to turn the head a bit to the left, on a right eye, so you can expose a bit more of it and get a better picture." He adds, "You may have to take two pictures, one with the patient's head tilted back and one with his head tilted forward, so you can see the lower and the upper part of the cornea and get the entire picture."

Dr. Chamon reminds those performing the topography to make sure the patient is comfortable and relaxed. "From the beginning, the patient will be trying to open his eyes very wide and he won't be able to maintain it. Do not ask him to push open his eyes wide until it is necessary. While you are focusing and centering, leave the patient relaxed. At the time you're going to obtain the picture, ask the pa-tient to blink once and open wide.

"In the end," he says, "you will take a better picture when you work with a patient like this."

Fixation

The corneal topographer looks at the reflection of the rings on the cornea to obtain its data. So that the rings are properly positioned, the pupil is lined up with a fixation target centered in the rings on the topography unit. Since it is possible for a patient to see the fixation target but not be lined up in the center of the system, Dr. Holladay recommends always asking the patient if the target he is looking at appears to be in the center of the hole. "If he says no," he continues, "we'll move the patient to get him to where the machine assumes he is—right in the middle of the system."

If a patient's vision is so poor that he can't even see the target, Dr. Holladay maintains there's no reason to perform the topography. "You can't trust the measurement if they can't see the target. You don't know where he's looking. It may even mislead you," he warns.

An easy way to determine if you can trust your measurement is to repeat the test. "If it's repeatable, then you know it's pretty good," says Dr. Holladay. Another way to pick up on possible errors is for the technician to note any differences between the maps of the patient's two eyes. "If you look at the maps, you should pretty much see a mirror image as a trend," notes Dr. Holladay.

The technician who really wants to produce the best maps will be adept at editing, says Dr. Chamon. The trained human eye is able to detect edges with more precision than computers do, so the technician should be able to edit the edge detection the computer has done. To get the most accurate map, Dr. Chamon says, the technician "must be able to pick out the error and erase it, and show where the proper ring is." Dr. Chamon asks his technicians to save all patients' maps in a way that they are easily retrievable.

Reading the Maps

Top Four Maps to Read

When examining the maps produced by corneal topography, Jack T. Holladay, MD, recommends review of:

• Refractive map: Tells you that you can correlate the power changes.

• Local radius map: Lets you pick up any very fine irregularities.

• Regularity map: Shows you the quality of the surface.

• Aspheric map: Shows you what the surface is like compared to the normal aspheric surface in a normal human eye.

To learn the most from the maps produced by a corneal topographer, Dr. Holladay recommends giving your attention to four maps: refractive power, local radius of curvature, regularity and asphericity. Eliminate the axial power maps, he advises, since they don't represent actual power changes in the cornea. The new re-fractive maps are better, he says, because they use Snell's Law to determine the power at every point on the surface, and not the keratometric ap-proximation formula as used in the past.

Dr. Holladay notes that several top-ographer manufacturers including EyeSys, LaserSight, Humphrey and Orbscan have set up a Holladay report on their machines. The Holladay re-port always includes at least the four maps he recommends examining. "Looking at those four maps and the Holladay report, you can determine just about anything you need to know about the patient," says Dr. Holladay. In explanation, he offers his article, Holladay JT. Corneal topography using the Holladay Diagnostic Summary. J Cataract Refract Surg. March 1997; 23: 209-21. "This article is a good reference for people," he says. "They can go back and read it before they look at the maps and they will mean a lot more to them." The refresher tips this article provides on the profile difference map and the distortion map may be especially helpful.

The profile difference map compares the shape of the patient's actual cornea to the "normal" aspheric cornea. The difference at every point is plotted in diopters on the map. This map may help to diagnose corneal diseases in which the cornea changes its overall shape, such as keratoconus, keratoglobus and pellucid marginal degeneration.

The distortion map correlates visual performance and optical irregularities in the cornea. As an example, Dr. Holladay offers anterior membrane dystrophy, where the refractive power maps and the profile difference map may be completely normal, but the distortion map usually shows many areas of optical irregularity, documenting the reason for poor vision.

• Comparing preop to postop. "In my opinion, the most important map, by far, for refractive surgery is the differential map," continues Dr. Chamon. "I don't see a postop patient un-less I have the differential map. The instrument takes the preop map and the postop map, and subtracts one from the other and gives me a third map. This third map is exactly what the laser has performed on the eye. It's my ablation profile." Calculation of the differential map is one reason why it is so important that the preop maps are saved and retrievable, notes Dr. Chamon.

Dr. Chamon also puts much value on the true curvature map (also called the local radius of curvature or tangential map). "Unfortunately, doctors are not as familiar with the true curvature map as they are with the axial map," he says. "They use the axial map because they are used to it. They know what is normal and what is not in the axial map. But if you are looking for precision, the true curvature map gives more accurate information."

• Using the scales. Dr. Chamon notes that a common mistake that doctors make when reading topography is not looking at the scales. "Most of the maps use standardized scales and I believe this is the best way to look at them. If you are using standardized scales, you must look at the scales when you look at the map, because the red areas may mean 42 D or they might mean 48 D," he explains.

Dr. Chamon believes that the absolute scale is harder to observe, with its many colors. "But if you use the absolute scale, you don't have to look at the scale, you know what the red means. It's really the doctor's preference, as long as he is aware of what scale is being used."

Watch for the Bumps

A bump on the inferior portion of the cornea, associated with thinning, is almost always diagnostic of keratoconus, notes Dr. Holladay. However, he says, a cone can be mimicked in eyes of someone who has worn a hard contact lenses for a long period, like 20 years.

| Corneal Topography Systems |

| Here is a partial list of corneal topography systems available: ATLAS System Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. 1-877-486-7473 humphrey.com CT200 Paradigm (801) 977-8970 paradigm-medical.com Keratron Topographer EyeQuip 1-800-393-8676 eyequip.com Orbscan, Orbscan II Bausch & Lomb 1-800-224-7444 orbscan.com System 2000 EyeSys Vision (281) 999-2229 eyesys.com |

However, he says that if the pachymetry shows you that the thickness is identical at both points, then you know the cornea is not thinning and the bump is not a cone. Doing this comparison allows the physician or technician to differentiate pseudokeratoconus in 20-year contact lens wearer from someone who truly has keratoconus. "That's very important to us in refractive surgery," notes Dr. Holladay, "so that we're not doing a thinning procedure on someone who's got a thin cornea — as opposed to the person who's got a little bump down there thanks to contacts."

New Developments

Topographer development is moving beyond the traditional machines that employ standard Placido ring technology to do a back calculation of curvature with spherical algorithms. While many of these older machines are still proving useful, some surgeons find that they do not provide the ex-tremely accurate curvature and elevation data necessary for the custom ablation planning process.

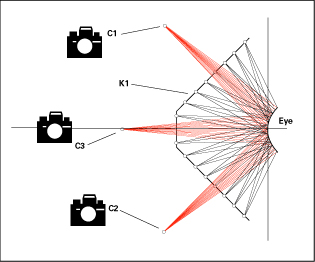

A relatively new device made available over the past year is the AstraMax stereotopographer by LaserSight Technologies Inc. (Winter Park, Fla.) The AstraMax, according to Dr. Holladay, the company's medical director, "overcomes the problems we've had with monocular topographers over the last 20 years because they have only one view. It's been like covering one eye and trying to judge depth. You can do it, but it's not very accurate or precise. The solution is a two- or three-camera system".

|

| The AstraMax's three-camera stereo imaging system provides precise peripheral values. (Top view of stereo camera imaging system.) |

Liz Best, director of marketing for LaserSight, says that the AstraMax, with its three-camera system, captures more than 13,000 data points in less than 0.2 seconds, increasing the accuracy and the speed of the exam. Common monocular topographers only collect between 7,000-9,000 data points. Ms. Best also notes that the AstraMax acquires six measurements in one exam using a common reference point, including posterior and anterior corneal topography, optical pachymetry, limbus to limbus topography and scotopic and photopic pupillometry.

Also in the multiple-camera topographer realm are the Humphrey Atlas System (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc.) and the Orbscan by Bausch & Lomb. Both are two-camera topographers that have moved away from the older eight-ring, spherical algorithm setup. Another example is the Keratron Topographer from EyeQuip that offers a Placido cone design and uses an arc-step algorithm when capturing and processing a map.

These features are shared with Humphrey's Atlas. John Austin, an At-las marketing representative, explains that this "cone of focus" feature, a ninth ring, provides that third reference point needed to triangulate data points. "This 'cone of focus,' plus the use of an arc-step algorithm," says Mr. Austin, "results in the extremely accurate measurements of curvature and elevation needed for today's custom ablation." He points to a VISX study1 that found the Atlas system provided repeatable elevation measurements accurate to within 1 µm of the actual height. Mr. Austin agrees that more surgeons will look for multiple camera configurations as custom ablation becomes the standard of care in refractive surgery.

Jack T. Holladay, MD, MSEE, FACS is a refractive surgeon based in Houston; visit www.docholladay.com. Wallace Chamon, MD, is a professor at the Federal University of Sao Paulo, Paulista School of Medicine, in Brazil. Contact him at visus@pobox.com.

1 Munnerlyn A, Tang V, Shimmick J. Measurement of Decentered Features by Corneal Topography. VISX Inc. Santa Clara, Calif.