However, studies from East Asia, particularly in the ethnic Chinese population, suggest that angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) is more prevalent worldwide than Western sources have assumed. Harry A. Quigley, MD, estimates that ACG will account for 26 percent of all glaucoma by the year 2010. And despite the greater prevalence of OAG, ACG accounts for almost half of the blindness caused by glaucoma today. This is because it can occur very rapidly and undermine vision much more aggressively than OAG, making it overall a more severe form of the disease.

Not Always Obvious

There may be a misconception, particularly among Western ophthalmologists, that most ACG appears in the form of an acute angle-closure attack. When we think of ACG, we typically think of the kind of situation we've all encountered in the emergency room, such as an elderly Chinese woman who comes in with acutely elevated pressure. But this is not the most common presentation of ACG; studies from Singapore and other East Asian countries have shown that most ACG is actually subacute or chronic.

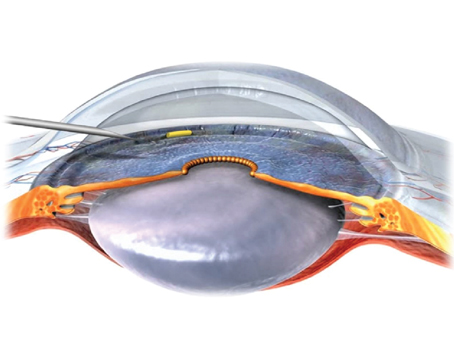

|

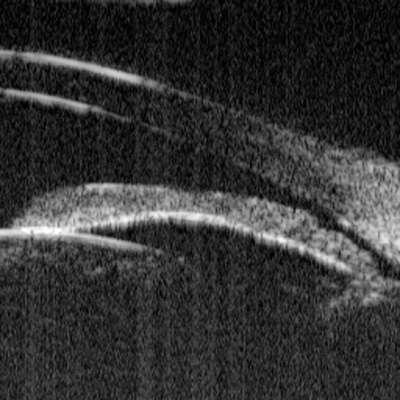

| Anterior segment OCT of a 40-year-old female shows narrow angles and a shallow chamber. Ike K. Ahmed, MD, FRCSC |

Cases of this kind normally don't present with pain or headache. Instead, they present more like OAG, in the sense that they're more insidious—and if you're not looking for them, you may not detect them. This is especially true for subacute ACG, in which the pressure may be normal when the patient is in the office during daylight hours. Later in the day, around dusk, however, the pupil will be more dilated and the angle may become occluded. The pressure rises gradually but doesn't reach a high enough level to cause pain or other symptoms, although it can be high enough to cause damage to the optic nerve.

For most Western ophthalmologists, cases like this may account for less than 10 percent of the glaucoma they see. They may not even be aware that some of their patients with glaucoma have this form or are at risk for it. But the reality is that we live in a multicultural society; cases like this are out there in our communities, so being aware of these different forms of ACG is important.

Diagnosing a Closed Angle

There are a number of ways to check for ACG. The simplest way to grade the angle is with the van Herick technique using the slit lamp. A common method for using this system is to have the slit illumination offset 60 degrees from the paraxial viewing scope. The grading system for the angle is as follows: 0 (no space between the iris and cornea at the peripheral limbus), 1 (space less than one-quarter of the corneal thickness), 2 (space exactly one-quarter of the corneal thickness), 3 (between one-quarter and one-half corneal thickness), and 4 (greater than half the corneal thickness). However, the gold standard for distinguishing ACG from OAG, and looking for ACG risk, is gonioscopy. It's simple, quick and causes the patient minimal discomfort.

Because ACG may be more prevalent—and more subtle—than many ophthalmologists realize, it's recommended that gonioscopy be performed in patients who are likely candidates for ACG, including those who appear narrow by van Herick exam, are older than 55 years, have a family history of glaucoma, or are of Asian descent.

Here are three ways to ensure that gonioscopy is effective:

• Minimize pupil constriction. Gonioscopy should be done with room lights off, using minimal slit- lamp illumination. Shining light in the pupil it will cause it to constrict, making it difficult or impossible to tell if the angle is in danger of closure.

• Be careful not to indent the eye. If you inadvertantly push against the eye, the change in pressure in the anterior chamber may open a narrow or occludable angle, leading to an incorrect diagnosis.

• Perform dynamic gonioscopy. Once you've detected a narrow or closed angle, then push gently on the eye to see whether the angle opens. If some parts of the angle have peripheral anterior synechiae (adhesions of the iris to the trabecular meshwork), that usually indicates a certain degree of chronic angle closure.

The most conclusive way to confirm the presence of an occludable angle is to perform the dark room prone provocative test. This maximizes the conditions that close the angle in the patient at risk for ACG, by keeping the patient in a dark room for about 45 minutes with his head down and the body in a prone position. (The patient should stay awake, because sleep-induced miosis may alter the results.)

Being in the dark allows the iris to dilate; having the head facing down allows the lens to move anteriorly and have greater chance for contact with the iris. A patient who is not at risk will show minimal change in intraocular pressure, while those at risk are likely to show a significant increase (usually 6 mmHg or more). Unfortunately, this test is time-consuming and cumbersome, making it impractical for most clinicians to use.

Imaging the Angle

Other ways to evaluate the condition of the angle include ultrasound biomicroscopy, and more recently the Visante OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec). UBM technology has the advantage of revealing extensive structural detail, including the ciliary body behind the iris. This ability can uncover important features of plateau iris or irido-ciliary cysts—both additional causes of ACG.

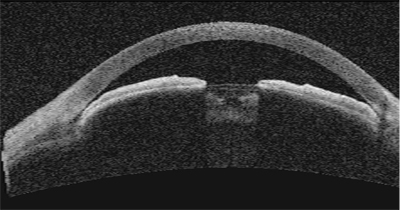

|

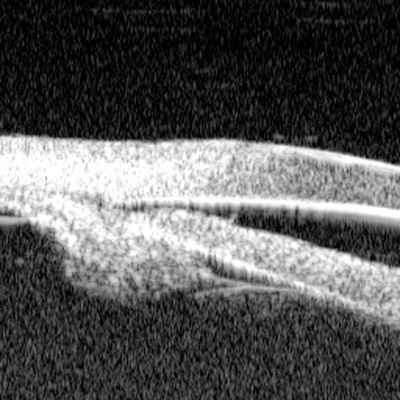

| UBM of the angle of a patient with iris cyst syndrome. Multiple iris cysts cause apposition and secondary angle closure. Shan C. Lin, MD |

For example, one family treated in my practice has iris cyst syndrome; it was not detected by the prior ophthalmologist, who didn't use UBM. Several members of the family had developed glaucomatous damage to their optic nerves. Laser peripheral iridotomies had previously been performed to treat what appeared to be simple pupillary block, but the angles remained narrow or closed. Because iris cysts were pushing the iris forward, the iridotomies did not completely alleviate the angle closure.

Many ophthalmologists have avoided the use of UBM technology in the diagnosis and management of ACG because of the need for placement of an eye cup and water bath. More recent advances have allowed UBM imaging without the need for the eye cup/water bath setup, in which a probe similar to a traditional B-scan probe is placed directly on the eye surface using a gel interface.

As an alternative, the Visante OCT is a quick, noncontact device that can image the anterior chamber angle. It doesn't require a significant light flash and an image can be generated within seconds, producing a scan that looks similar to the UBM. (For an example, see page 80.) However, a current disadvantage is that the Visante can't image the ciliary body behind the iris.

Future studies will shed light on whether the Visante OCT can detect at-risk patients as determined by gonioscopy, or even those missed by gonioscopy.

Seeing Beyond Pupillary Block

Ophthalmologists often assume that pupillary block is the causative mechanism in the vast majority of ACG cases. So, patients who are seen to have a narrow angle usually receive a laser iridotomy, creating a small hole in the iris that allows aqueous to bypass the pupillary block. It's a safe procedure with relatively low risk.

Is laser iridotomy effective in the long run? In a Singaporean study, the success rate in preventing long-term IOP rise in fellow eyes of patients who suffered an acute ACG attack was 89 percent, with an average follow-up of four years.2 However, although iridotomy appears very effective, a significant proportion still develop glaucoma later.

One of the reasons, as noted above, may be the cause of the angle closure. If the etiology is actually iris cysts or plateau iris, putting a hole in the iris may not really help (unless the patient has a mixed mechanism including pupillary block). For a patient who has plateau iris, for example, effective treatments include the use of pilocarpine and argon laser iridoplasty. The latter causes the iris to retract, opening the angle.

Because laser iridotomies are not always effective, after a laser iridotomy has been performed, postoperative care should include re-evaluation of the angle, including gonioscopy.

The assumption that pupillary block is the cause of ACG in the vast majority of cases is now being challenged by several researchers. In a recent study from a clinic in India, 55 patients were examined by slit lamp and UBM after laser iridotomy; 60 percent were found to still have a narrow angle.3 UBM testing revealed that the majority of these patients had plateau iris. These results suggest that simply treating with a laser iridotomy may leave a lot of patients at risk in some populations.

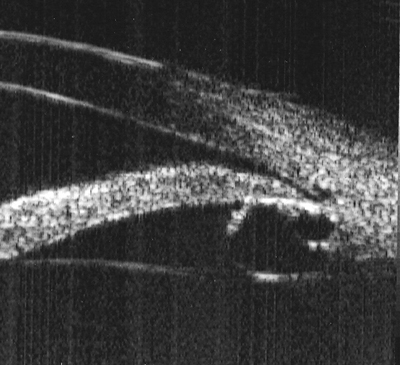

|

| UBM of a narrow angle with papillary block. The iris is bowed forward by aqueous trapped in the posterior chamber. Shan C. Lin, MD |

|

| Plateau iris syndrome. The iris plane is flat; the angle is appositional due to the anterior position of the ciliary processes (note the lack of a ciliary body sulcus). Shan C. Lin, MD |

A large population-based study of Chinese-Americans would help determine the true prevalence of ACG in this at-risk group. We're currently conducting a pilot study in the Chinese population of San Francisco, including UBM assessment of the angle in those at risk for ACG.

Still a Widespread Problem

Treatment for and prevention of these conditions are relatively straightforward, but ACG is still extremely common, primarily for three reasons. First, narrow or closed angles may be missed if the clinician is not vigilant in looking for them; gonioscopy should be performed more frequently, particularly in patients at higher risk. Second, even when diagnosed, treating with a laser peripheral iridotomy may be leaving a number of patients at risk because of causes other than pupillary block. Third, most ACG, and most risk for it, is found outside the United States, in China, Mongolia and other countries in East Asia. In many of these countries, facilities and equipment for detection and treatment of ACG are not readily available.

Ophthalmologists in the United States may have limited ability to help individuals with ACG in other countries. But we can certainly improve the effectiveness of our own care by checking for narrow angles and keeping in mind that a peripheral iridotomy may not resolve the problem in many patients. Also, we can do our best to make ophthalmologists around the world more aware of the problem.

With luck, come 2010, far fewer people will lose their vision to this type of glaucoma.

1. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:253-4.

2. Gazzard G, Friedman DS, Devereux JG, Chew P, Seah SK. A prospective ultrasound biomicroscopy evaluation of changes in anterior segment morphology after laser iridotomy in Asian eyes. Ophthalmology 2003;110:630-8.

3. Garudadri CS, Chelerkar V, Nutheti R. An ultrasound biomicroscopic study of the anterior segment in Indian eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2002;11:502-07.