With many surgeons wary of creating ectatic corneas with their LASIK procedures, the interest in using thinner flaps has risen. Some surgeons routinely use flaps in the 130-µm range or thinner, using either mechanical microkeratomes or femtosecond lasers. Here's a look at the advantages and disadvantages of thin-flap LASIK, and the results some doctors are experiencing with it.

The Move Toward Thin Flaps

Though the definition of a thin flap differs somewhat from surgeon to surgeon, most would agree that a flap equal to or thinner than 130 µm is thin.

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD, clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at

"At that time the instrumentation was offering flaps of 160 to 200 µm," he says. "Of course, initially, the concern was for the flap to be thick enough to avoid problems with flap repositioning such as striae, flap slippage, inflammation and cut irregularity. Three things have evolved in the last 15 years: First, our instrumentation for creating the flap has become quite sophisticated. This has gone along with our knowledge of how to use that instrumentation to cut flaps with a high level of certainty. Second, we're trying to avoid reaching very low levels into the cornea out of the fear of making those corneas ectatic in the future. Initially, we started without any floor for our ablation. Then, arbitrarily, the 250-µm floor was set. Now, most refractive surgeons would agree a 300-µm floor is desirable. Since the average corneal thickness is 540 µm, in order to leave a 300-µm floor, you're limited to working with the top 240 µm. And if we assume an ablation range will reach to the level of 100 to 120 µm, then you're left with a flap that, by definition, is 120 µm thick. That's a thin flap, though today I'd consider a 'thin' flap to be any near or at 100 µm." He says the third factor pushing surgeons toward thin flaps is that modern ablations, with custom software and enlargement of the optical zone, are removing more tissue per diopter than 15 years ago. He and others also say the thinner flaps allow for a more rapid visual rehabilitation.

Dr. Kanellopoulos says in a study of 2,500 LASIK cases he performed using the Moria M2 microkeratome, he achieved flaps around 115 µm thick, and only had one free cap and one buttonhole. He says in terms of visual results, the one-day results were only two percentage points away from the one-month outcomes.

Paul Dougherty, MD, of Los Angeles' Jules Stein Eye Institute, performed a study of thin-flap LASIK using the BD K-3000 microkeratome (BD Ophthalmic Systems, Waltham, Mass.), comparing the instrument's 130-µm head to the 160. There were 155 eyes of 80 patients in the thin-flap group and 279 eyes of 148 patients in the thicker-flap group. The overall results were almost identical in terms of safety and efficacy, with a single partial flap in the 160-µm group.1

Dr. Dougherty has been using thin flaps for around three years to minimize the risk of ectasia. Most of the time, he says he shoots for a flap between 100 and 120 µm. "I'm able to consistently and safely do it with both a conventional microkeratome, the Nidek MK-2000, and a 60-Hz IntraLase," he says. "I can get about a 105-µm flap with the MK-2000

±15 µm, and 100-µm flap with the IntraLase, ±10 µm."

Thin flaps aren't without risks, though.

"There are some inherent risks with making a thinner flap," explains John Doane, MD, of

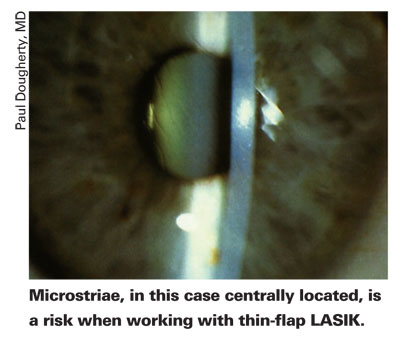

Dr. Dougherty says though his results with thin flaps have been excellent, he does notice striae. "In the study I published, I didn't see any difference in microstriae between the 130-µm flaps and the 160," he says. "But now, as I use thin flaps more and more, I see a few more cases of peripheral microstriae where the flap lies over the treatment zone, but they're not visually significant." He says that he may be a little less inclined to go for an ultra-thin (100-µm) flap in patients with thicker corneas or in hyperopes, the latter of which don't need that much tissue removed, since this minimizes the risk of microstriae in patients who don't really need ultra-thin flaps anyway.

Sub-Bowman's Keratomileusis

Some surgeons are taking the idea of thin-flap LASIK even further, into the 70-µm range, using the IntraLase laser to cut just beneath Bowman's to try to combine the benefits of LASIK with those of a surface procedure. The diameter of these super-thin flaps is 8.5 mm, to avoid severing more corneal nerves in the periphery.

"The question is: If we're making flaps that are thin enough and with a small enough diameter, can we cut so few corneal fibers that we get the wound healing and biomechanical advantages of surface ablation with the recovery powers of LASIK?" muses Dan Durrie, MD, who has studied the procedure. "That would be a big deal." He says sub-Bowman's keratomileusis, or SBK, may help maintain the integrity of the cornea, and he cites the work of John Marshall, PhD, of

To study SBK, Dr. Durrie and

Some surgeons wonder if flaps this thin can be made safely time and again.

"I'm all for making things better with science and technology," says Dr. Doane, "but the issue I'd have with SBK is that you'd have to literally be right under Bowman's membrane every time without going through it. This is a large risk to take, because we know that when you incise Bowman's layer it has a greater tendency to produce new collagen that can create haze or scarring. You'd have to be dead-on each time, not just so-so. If you perform SBK and incorporate Bowman's in the central 3.5 mm and leave a scar there, you could end up with lamellar haze."

Dr. Kanellopoulos also questions SBK's usefulness. "Personally, I don't think it's really necessary to go that thin with a flap," he says. "The only reason to go that thin with a flap would be if the patient has a very thin cornea and a lot of myopia to treat. For those eyes, I'd look at making the correction on a different level, such as an implant."

1. Dougherty PJ. The thin-flap LASIK technique. J Refract Surg 2005;21:5:S650-4.