Vitreoretinal surgical fellowship and ophthalmology residency education have deep roots in the apprenticeship Halsted model of surgical training, i.e., “see one, do one, teach one.” In the early days of surgical retinal fellowships, one-on-one apprenticeship was the modus operandi of training, such as Dr. Jose Berrocal under Dr. Charles Schepens or Dr. Thomas Aaberg under Dr. Robert Machemer. We still see elements of the apprenticeship model incorporated into contemporary post-graduate education: Residents and fellows serve under the guidance of faculty mentors for a set number of years and achieve a set number of surgical and procedural requirements. More recently, external stakeholders (e.g., the government, the public, third-party payers, etc.) have placed increasing pressure on educators to provide proof of quality and competency in education. As a result, medical education has transitioned to a core competency-based curriculum, per the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

|

Ophthalmology residency programs currently adhere to the ACGME six core competencies: patient care; medical knowledge; practice-based learning and improvement; interpersonal and communication skills; professionalism; and systems-based learning.1 Other than ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery, ophthalmology fellowships (including vitreoretinal surgery) are not ACGME accredited. However, the Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology (AUPO) Fellowship Compliance Committee has outlined fellowship program requirements, most of which dovetail with these ACGME core competencies.2 Challenges in modern vitreoretinal surgical education include standardizing the assessment of medical knowledge and surgical competency. On the other hand, technological advances, such as virtual simulations and video technology, have revolutionized ophthalmic and vitreoretinal education; they’ve facilitated development of examination and surgery skills while simultaneously improving trainee competency and patient safety.

Here, we review medical training in ophthalmology, with a focus on vitreoretinal surgery, through the lens of established ACGME core competencies. We also briefly review the recent challenges, opportunities, and creative solutions in ophthalmic education amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Medical Knowledge and Care

Medical knowledge and patient care encompass two of the six ACGME core competencies, and education in these disciplines can be enhanced both in the clinic and operating room setting through various methods:

• Education in the clinic. In the ophthalmology clinic setting, examination and imaging interpretation are critical diagnostic skills. Examination techniques for the retina and vitreous can be particularly challenging, since faculty educators frequently can’t verify what trainees are seeing. Appropriate scleral depression to identify retinal pathology can be difficult to learn for many reasons, including patient discomfort, examiner positioning and technique. Furthermore, a retrospective study suggests that trainees’ peripheral indirect ophthalmoscopy and laser retinopexy skills have become increasingly inadequate.3

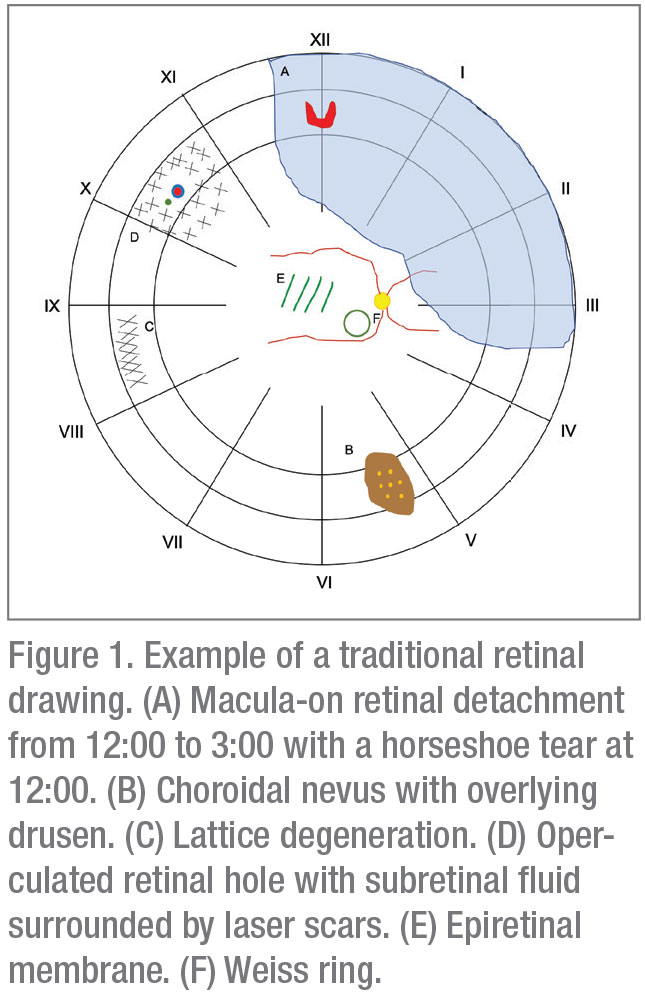

There are multiple potential strategies to combat the decline in retinal examination skills. For one, faculty could require residents and fellows to still use “old school” tools, such as retinal drawings, which are a dying art in the age of electronic health records and ubiquitous ultra-widefield fundus photography. Being forced to put pen to paper (or mouse to screen, in the case of an EHR drawing) further motivates the trainee to develop good habits (Figure 1). These drawings also encourage novices to actively recall their exam and provide an opportunity for faculty and mentees to review missed or omitted examination findings.

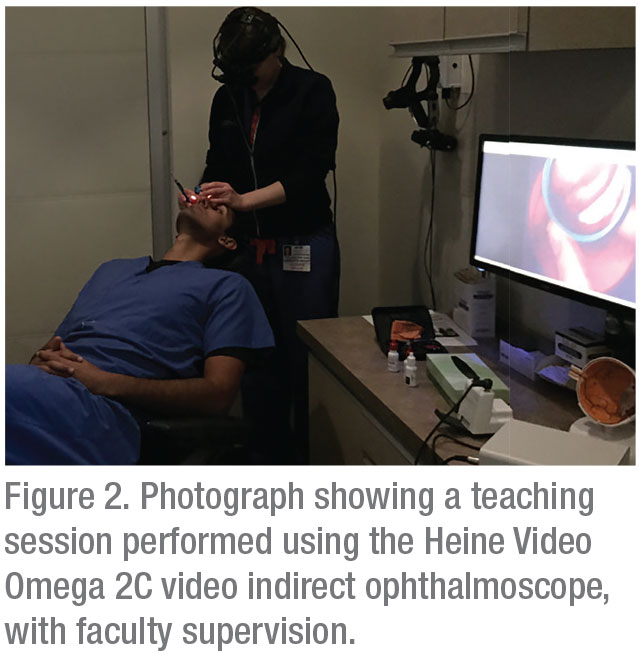

Technological aids may also be useful in building fundus examination skills. Video indirect ophthalmoscopy consists of a traditional indirect ophthalmoscope attached to an external display, allowing for real-time observation of the same image viewed by the examiner (Figure 2). The screen image can also be recorded for later review. In a prospective, randomized study from our group, VIO proved to be a useful tool for increasing resident efficiency and confidence with the peripheral fundus exam.4 VIO trainees in the study group were able to receive real-time feedback and instruction from faculty to improve their indirect ophthalmoscopy and scleral depression examination skills.

In addition to emphasizing exam technique, reviewing imaging in the clinic should be an essential practice in ophthalmic and vitreoretinal education. Specifically, the AUPO Fellowship Compliance Committee recommends that vitreoretinal fellows develop a thorough understanding of fluorescein angiography, electrophysiology, optical coherence tomography, ultrasound and radiology.2 Given the pace of many vitreoretinal clinics, it may be more efficient for faculty and trainees to “round” on interesting and educational fundus photos, OCT scans and FA images after all patients have been seen. Outside of clinic, many institutions host regularly scheduled retinal imaging rounds as part of their resident and fellow educational curriculum; for example, Wills Eye Hospital offers Retina Imaging Rounds for free every other week via livestream.5

• Education in the OR. Molding trainees into skilled and competent surgeons is critical in ophthalmology and vitreoretinal surgery education. As such, it’s housed as a distinct competency within the ACGME core-competency of patient care.6 Many vitreoretinal surgical fellowships still rely heavily on the Halsted apprenticeship approach to surgical training. Watching and learning from an expert, skilled faculty mentor is invaluable. Meanwhile, trainees gradually develop autonomy from abundant opportunities to care for surgical patients.

Today, technology supplements the apprenticeship model. Technological advances now allow vitreoretinal fellows and trainees to build baseline knowledge, experience and competency while optimizing patient safety.

|

The modern approach to surgical training includes online surgical videos and structured curricula, wet lab teaching courses and virtual simulation. YouTube, the American Academy of Ophthalmology Ophthalmic News and Education Network (https://www.aao.org/clinical-education), and other online video databases provide thousands of videos to observe and learn surgical steps. For retinal surgery specifically, the Vit-Buckle Academy (VBA, https://vitbucklesociety.org/vit-buckle-academy) is the first step-by-step video-based curriculum available online. In addition, industry representatives provide annual surgical wet lab courses, offering opportunities to practice and develop surgical skill in an intimate setting, with several companies dedicating events specifically to residents and fellows.

Virtual simulations of cataract surgery have been extensively studied; however, only four reports to date have evaluated the vitreoretinal modules of the EyeSi Surgical Simulator (VRmagic, Mannheim, Germany).7 While the studies suggest that the EyeSi can distinguish between experienced and inexperienced vitreoretinal surgeons, there is not yet published data supporting the transfer of skills to the operating room.7 More studies validating simulation training need to be done before drawing further conclusions on its efficacy as a teaching model, but its potential certainly suggests an increasing importance in the future.

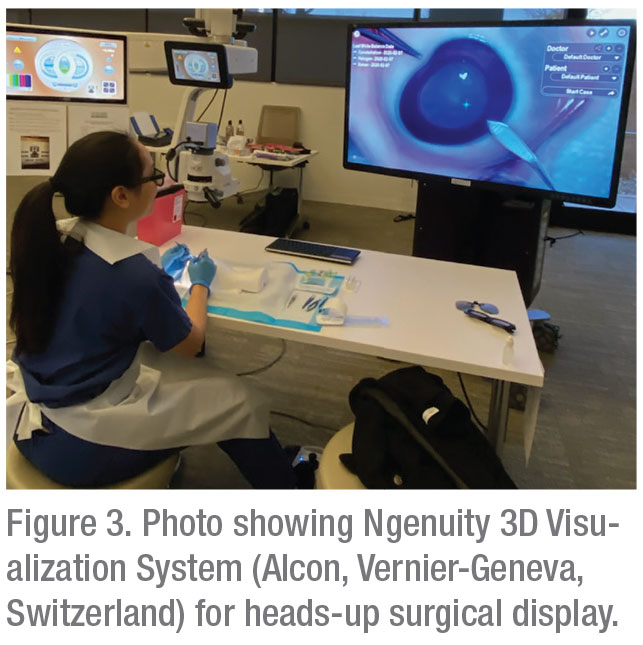

In the OR, there are a number of innovations that can supplement vitreoretinal surgical education due to improved visualization. With the ability to provide better real-time visual feedback, the chandelier-assisted scleral buckle allows an assistant to observe examination and treatment of the peripheral retina with either cryotherapy or laser.8 Newer heads-up 3-D visualization systems are competing with traditional microscopes and allow all OR observers access to the primary surgeon’s view (Figure 3). There will be a learning curve with this technology; a prospective study suggested that macular peel time was significantly longer in the 3-D display group, compared to a microscope.9 Still, if these systems become more common, the advantages should easily exceed the disadvantages for surgical education.

Approaches to Learning

Next, we review two more ACGME core competencies: practice-based learning (PBL) and systems-based learning (SBL). We discuss how to further PBL and SBL through the lens of new media and amidst the pandemic.

• Education in 2020 with new media. PBL includes processes and behaviors that foster improvement and continual education in best practices, frequently through review of current literature.1 In the core competency-based curriculum, PBL is traditionally executed through journal clubs, which are required on a quarterly basis by the AUPO Fellowship Compliance Committee.2 Outside of traditional journal clubs, new media such as podcasts, webinars, online continuing medical education courses and virtual conferences provide abundant opportunities for practice-based learning. The AAO also provides several online sources for education, including the ONE Network, which provides summaries of recent high-yield ophthalmology publications. Further informal opportunities for PBL include non-peer-reviewed sources like Facebook groups, Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram text groups, and YouTube. For example, the American Retina Forum is available to vitreoretinal trainees and attendings on Facebook and Telegram as an informal venue for sharing interesting cases and asking clinical questions in a HIPAA-compliant fashion.

|

Straight From the Cutter’s Mouth: A Retina Podcast (SFTCM) was created by our group to provide educational content curated for vitreoretinal specialists, as well as CME credits via the AAO. Episode topics include journal clubs, medical and surgical management techniques, and fundamentals of practice management. Reflecting the increasing demand for new media, the listener base of SFTCM grew quickly, from 684 downloads in the first quarter of 2017 to 16,016 downloads in the third-quarter of 2018.10 Demographic data from a voluntary survey of all SFTCM podcast listeners at one year showed that 65.7 percent of listeners are between the ages of 25 and 34.10 This suggests that the primary consumers are either still in training or recently out of training, indicating that podcasts and other new educational media will likely see continued rapid growth as a younger, more tech-friendly generation grows up over the next decade. In a separate survey sent to retinal society members, generally an older cohort, survey respondents stated that national conferences were still their most preferred educational medium, and reading journal articles and listening to grand rounds were rated as significantly more likely to change clinical practice than podcasts.11 Still, podcasts have a strong standing in the retina community, with 41.1 percent of survey respondents listening to at least one medical podcast a week.11

In complement to problem-based learning, SBL refers to the “ability to work within the system and to call on resources within the system to provide optimal care to the patient.”12

SBL modalities may include traditional morbidity and mortality conferences or opportunities to perform a root-cause analysis of a significant clinical event. Quality improvement projects are also opportunities to implement SBL. While currently there aren’t publicly available digital SBL opportunities for vitreoretinal surgeons, one would expect that this space will be filled given recent events.

• Medical training and

COVID-19. The pandemic has introduced new challenges to ophthalmology education, including disruptions in medical and surgical institutional didactics, elimination of traditional in-person conferences, and drastically decreased clinical volumes. This challenge has birthed a revolutionary movement that has fostered creativity and broadened inclusivity through virtual education and conferences. Major domestic organizations such as the AAO, the American Society of Retinal Specialists, Retina Society, Retina World Congress, and The Vit-Buckle Society have either hosted online webinars or transitioned their annual in-person meeting into a digital interactive format. These meetings provide opportunities to discuss difficult surgical cases with a problem-based and video-based learning approach in mind. For example, VBS converted its annual spring meeting into a four-part series of online meetings using the Zoom platform, with audience members able to participate in discussions and post questions for panelists in real time. More than 900 participants registered for the first part of the series, more than double the typical in-person attendance. The numbers demonstrate the potential for greater inclusivity from virtual educational conferences, as concerns over physical meeting space are eliminated and replaced with an easily solved problem of digital bandwidth.

In addition, with drastically decreased clinical and surgical volumes, the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to an explosion in telemedicine. Prior to the pandemic, ophthalmology’s use of telehealth was primarily geared towards store-and-forward mechanisms for screening for diseases like diabetic retinopathy.13 Due to COVID-19 restrictions and fears, real-time telemedicine visits and/or hybrid real-time visits with separate office testing have increased out of necessity.13 With telemedicine on the rise, it’s important to include and expose trainees to telemedicine tools, such as educating patients about at-home visual acuity and Amsler grid testing.

In New York City, an epicenter of COVID-19 cases, the pandemic had a dramatic impact on ophthalmic education. In the wake of tthe ragedy, the NYC ophthalmology residency programs banded together, giving rise to multi-institutional didactic series.14 Residents had access to 45 lectures across different ophthalmology program sites. This inter-institutional didactic curriculum was so successful that it’ll remain in place post-CO-VID.14 The adaptability of the NYC programs exemplifies the collegial spirit of academic cooperation in education, despite discouraging circumstances.

“Soft” Skills Can Be Hard

The “soft” talents of interpersonal and communication skills, as well as professionalism, are difficult core competency skills to measure. As ophthalmologists, we sometimes have to break the bad news of permanent visual impairment to our patients. Although it’s a critical skill, discussing poor outcomes with patients is rarely taught as a communication skill in residency or fellowship training. One online survey found that 88 percent of participants stated that formal training in communication skills for breaking bad news would be beneficial.15 Sarah Hilkert Rodriguez, MD, while a resident at the Havener Eye Institute at Ohio State University, suggested a formal curriculum for breaking bad news in six steps, through the mnemonic SPIKES, which is composed of the following:

• Setting: Arrange for privacy and avoid interruptions;

• Perception: Inquire about how much the patient already knows;

• Invitation: Discuss how much the patient wants to know;

• Knowledge: Avoid jargon, allow moments of silence;

• Empathy: Acknowledge and validate patient emotions;

• Summary: Confirm understanding, address patient-specific goals.16

In Dr. Hilkert’s study, all 11 resident study participants stated that they would use the SPIKES approach for breaking bad news in their clinical practice.16

In summary, ophthalmology and retinal surgical education has evolved drastically from its origins in individual apprenticeship to today’s more broad, inclusive, core-competency-based model. Technological advancements in surgical training tools and online content sharing have led to exceptional innovation in medical training in ophthalmology in general, and vitreoretinal surgery in particular, and the recent challenges brought about by the pandemic have further accelerated the shift towards digital education.

If we’ve learned anything from the last few months, it’s to expect the unexpected. With that in mind, we look forward to seeing more ingenious and creative educational solutions in ophthalmology beyond what we’ve reviewed here. REVIEW

Dr. Hua is chief resident at the Roski Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Dr. Sridhar is an associate professor of clinical ophthalmology and vitreoretinal surgery at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. Neither author has any financial interest in any of the products discussed.

Correspondence: Jayanth Sridhar, MD, Department of Ophthalmology, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 900 NW 17th Street, Miami, FL 33136. Email: jsridhar1@med.miami.edu.

1. Lee AG, Carter KD. Managing the new mandate in resident education: A blueprint for translating a national mandate into local compliance. Ophthalmology 2004;111:10:1807-1812.

2. Program requirements for Fellowship Education in Surgical Retina & Vitreous. Association for University Professors of Ophthalmology. https://aupofcc.org/system/files/resources/2019-08/FCC_Program Requirements_Retina.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2020.

3. Petrou P, Lett KS. Effectiveness of emergency argon laser retinopexy performed by trainee physicians: 10 Years later. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retin 2014;45:3:194-196.

4. Sridhar J, Shahlaee A, Mehta S, et al. Usefulness of structured video indirect ophthalmoscope—Guided education in improving resident ophthalmologist confidence and ability. Kidney Int Reports 2017;1:4:282-287.

5. Live Streamed Webinars. Wills Eye Hospital.

6. Ophthalmology Milestones. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/OphthalmologyMilestones2.0.pdf?ver=2020-01-17-145640-583.

7. Lee R, Raison N, Lau WY, et al. A systematic review of simulation-based training tools for technical and non-technical skills in ophthalmology. Eye 2020. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0832-1

8. Hu Y, Si S, Xu K, et al. Outcomes of scleral buckling using chandelier endoillumination. Acta Ophthalmol 2017;95:6:591.

9. Talcott KE, Adam MK, Sioufi K, et al. Comparison of a three-dimensional heads-up display surgical platform with a standard operating microscope for macular surgery. Ophthalmol Retin 2019;3:3:244-.

10. Venincasa MJ, Cai LZ, Chang A, Kuriyan AE, Sridhar J. Educational impact of a podcast covering vitreoretinal topics: 1-year survey results. J Vitreoretin Dis 2019;3:5:358-362.

11. Venincasa MJ, Kloosterboer A, Zukerman RJ, et al. Educational impact of podcasts in the retina community. Ophthalmol Retina 2020 May 5;S2468-6530:20:30187-1.

12. Lee AG. Graduate medical education in ophthalmology. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:9:1290.

13. Kalavar M, Hua HU SJ. Teleophthalmology: An essential tool in the era of COVID-19. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020 [online ahead of print].

14. Chen RWS, Abazari A, Dhar S, et al. Living with COVID-19: A perspective from New York area ophthalmology residency program directors at the epicenter of the pandemic. Ophthalmology 2020;127:8:e47-e48.

15. Zakrzewski PA, Ho AL, Braga-Mele R. Should ophthalmologists receive communication skills training in breaking bad news? Can J Ophthalmol 2008;43:4:419.

16. Hilkert SM, Cebulla CM, Jain SG, et al. Breaking bad news: A communication competency for ophthalmology training programs. Surv Ophthalmol 2016 2016;61:6:791-798.