Tube shunts have their own challenges and complications, of course, which is why most surgeons haven’t simply given up trabeculectomy and switched to using them as their mainstay surgical option. Their use is increasing, however, at least partly because of improvements in surgical technique and in the devices themselves, as well as new ideas about preventing tube erosion and fibrosis.

Here, three surgeons with extensive experience using these devices offer their suggestions for minimizing unwanted complications, improving long-term bleb survival and making sure that a second tube—when necessary—is effective.

The Case for Using Tubes

Herbert P. Fechter III, MD, who practices at Eye Physicians & Surgeons of Augusta in Augusta, Ga., says he typically implants two to four glaucoma shunts per week, mostly Baerveldts but also some Ahmeds. “I’ve noted a shift from trabeculectomy to glaucoma drainage implants over the past 12 years,” he says. “I think the Tube vs. Trabeculectomy Study had a lot to do with that, along with top-tier academic centers promoting the use of tube surgery. More recently, the Ahmed vs. Baerveldt Study has also persuaded many surgeons that tube surgery has a place earlier in glaucoma management.”

| ||||||

Dr. Fechter says he implants a Baerveldt about 90 percent of the time and an Ahmed the other 10 percent of the time. “The one I choose depends on the patient,” he explains. “I tend to reserve the Ahmeds for cases of neovascular glaucoma or angle closure where the pressure is very high and I need to get it down quickly. But if I think I can manage to maintain moderate pressure in the early postoperative period, I prefer to put in a Baerveldt. It has a lower profile than the Ahmed, and the five-year treatment outcomes in the Ahmed Baerveldt Comparison Study show that pressures are a couple of points lower with the Baerveldt. I also have a bias; during my fellowship training the majority of tube patients received the Baerveldt implant.

“At the outset, surgeons usually have some apprehension about the complications associated with each of these implants,” he adds. “They may be reluctant to put in a tube out of fear of hypotony, diplopia or hyphema. The package insert lists a number of complications, and over the years, I’ve observed each one of them at one time or another. For most patients, though, it’s a very reliable technique for lowering pressure.”

Scar Tissue and Fibrosis

Darrell WuDunn, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Eye Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, notes that the most common cause of tube shunt failure is scar tissue forming around the plate. “Over time you may get a really thick capsule around the plate that prevents the fluid from getting out of the reservoir,” he explains. “You can usually tell that this is the problem because the bleb overlying the plate will be thick, dome-shaped and very elevated—higher than you’d expect it to be. In contrast, if the bleb is very low that probably means a tube blockage is the source of the problem. Fluid has to travel through the tube to the reservoir to create the bleb, so if the bleb is flat, you know the fluid is not getting into it.

“If the problem is scar tissue around the implant, you can revise it either of two ways,” he continues. “You can take a 27- or 30-ga. needle and poke holes into the capsule beneath the conjunctiva to see if you can get the fluid to flow through the holes. Of course, you have to be careful that you don’t cause leakage. Usually you start by inserting the needle far away from the bleb itself and track beneath the conjunctiva; then when you get to the capsule, you start poking holes in it. That maneuver can release some of the fluid from the reservoir so it can leak into the surrounding space and out through the conjunctiva.”

Dr. WuDunn notes that this approach is not guaranteed to be successful. “Back in 1997 Philip Chen and Paul Palmberg published a study which looked at a series of 21 eyes that underwent needle revisions.1 They found that it worked only 43 percent of the time after one year,” he says. “However, it’s a simple procedure that can be done in the office, which is a big advantage.

“If that doesn’t work, you can bring the patient to surgery and do a surgical revision of the bleb over the plate by excising the capsule,” he continues. “That means opening the capsule, removing the thickened scar tissue and then sewing it closed again. Three or four articles have looked at the success rate of this approach, including one we published back in 2000. The success rate isn’t all that great; this only succeeds in restoring pressure control long-term—say, for more than one year—40 to 60 percent of the time. All of those studies showed similar results, and they weren’t much better than needling of the bleb. So one could argue that if your success rate isn’t going to be better than needling, you might as well try needling in the office rather than bringing the patient to the operating room.”

The Cytokine Connection

As with many things in life, the best solution to the problem of bleb scarring may be prevention. Jeffrey Freedman, MD, PhD, professor of clinical ophthalmology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, has recently made notable progress in that area. (In the past, Dr. Freedman has worked closely with Professor Anthony Molteno, developer of the Molteno shunt.) “The major problem that affects all of these implants is fibrosis, which is the primary reason a bleb stops draining,” he says. “Once they stop draining, they’re worthless. So the real concerns here have to do with bleb physiology. That’s the issue Dr. Molteno and I have spent most of our time working on in recent years.”

Dr. Freedman explains that there’s a profound connection between elevated pressure and the development of fibrosis, a connection moderated by cytokines. “I learned about the connection between pressure and cytokines from one of my early collaborators who was a rheumatologist,” Dr. Freedman says. “Rheumatologists work with cytokines all the time because cytokines are associated with arthritis and similar problems. My colleague introduced me to the concept of a Selye pouch, invented by Hans Selye, MD, a doctor who did a lot of research on how the body responds to stress. If one injects air under the skin of a rat and increases the pressure inside it to stress the tissues, one creates what is known as a Selye pouch. Research has shown that increasing the pressure inside the pouch causes the tissues to produce TGFb-2 (transforming growth factor beta). My colleague noted that the bleb we create is exactly the same as a Selye pouch.

“What our own research has shown,” Dr. Freedman continues, “is that when the pressure in the eye goes up, proinflammatory cytokines are formed, particularly TGFb-2. These cytokines lead to the formation of fibrosis. What’s important to understand is that the stimulus for development of these cytokines is the elevated pressure itself. The pressure causes a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier and the formation of the cytokines. We have also shown that the level of TGFb-2 in the aqueous is prognostic of whether or not the bleb will survive or fail.

“Recently we compared the aqueous of normal eyes that were having cataract surgery and eyes in which we did glaucoma implants—in other words, eyes in which the pressure was elevated,” he says. “Furthermore, we compared both of these to the fluid inside the bleb during the hypertensive phase, where the pressure is very elevated. The data showed clearly that as the pressure goes up, the concentration of cytokines becomes higher, especially the very proinflammatory TGFb-2 and monocyte chemotactic protein1 [MCP-1].”

| ||||||

Minimizing Fibrosis

Dr. Freedman says the aqueous present in the eye at the time of surgery is referred to as glaucomatous aqueous. “This aqueous is called that because having been exposed to high IOP, it’s laden with cytokines,” he explains. “Allowing this aqueous onto the plate surface will result in an immediate pro-inflammatory reaction, which may result in the development of a more fibrotic and less functional bleb. This has been shown to occur in valved implants, which do allow aqueous onto the plate surface immediately.2 Non-valved implants don’t allow this to happen because the tubes are temporarily occluded; aqueous only reaches the plate surface after the IOP has been lowered by other means. Our research has shown quite clearly that if the aqueous doesn’t reach the plate until the pressure has been lowered, the cytokine content is much lower, which results in a less-severe fibrotic reaction.” Dr. Freedman points out that allowing cytokine-laden fluid onto the surface of the plate also results in a more frequent and severe hypertensive phase. “This in turn results in a bleb that ultimately is more fibrotic and less functional,” he says.2

“The reason for the use of valved implants is the ability of these implants to prevent postoperative hypotony in most cases,” he adds. “Nevertheless, it’s becoming more apparent that blebs associated with non-valved implants are likely to be less fibrotic and more functional in the long term. I believe this can be explained by the cytokine content of the aqueous. We have recently submitted a paper for review which illustrates this concept.

“Several researchers from Iran saw a poster of mine at ARVO back in 2006 discussing the presence of cytokines in the aqueous and explaining that the stimulus for the development of the cytokines was pressure,” he continues. “So, they conducted a study focused on Ahmed implants. They had the patients in one group take carbonic anhydrase inhibitors [following surgery] to decrease the formation of aqueous and keep the pressure low. Their data showed that if you can keep the pressure low during the development of the bleb, the Ahmed does much better. They surmised that this was because cytokines were not being formed, due to the low pressure.3 Our studies have shown this explanation to be correct.”

Dr. Freedman says this has caused him to modify his technique when implanting glaucoma tube shunts. “Now, we look at our blebs very carefully,” he says. “As soon as the pressure goes up, I tap the bleb. If the bleb is tapped by removing aqueous whenever the pressure becomes elevated, the pressure can be controlled, with or without the use of medications, thus reducing the level of cytokines in the aqueous. If the cytokine content is lowered, it results in a more successful bleb.”

Managing Tube Blockage

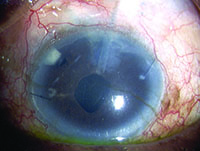

“One of the things that can cause a tube to fail is blockage,” notes Dr. WuDunn. “The tube can be blocked by vitreous or fibrin caught in the opening. It can also be blocked by iris tissue, if the iris is floppy or inflammation causes the iris to migrate into the tube.

“To resolve the problem, it’s important to determine the etiology of the blockage,” he says. “If you can see the block, whether vitreous, fibrin or iris, you may be able to use a laser to disrupt it. Typically you’d use the Nd:YAG laser, although sometimes the argon laser will work. The Nd:YAG laser is very precise, and the inside diameter of the tube is large enough that you can create a microexplosion inside the tube and not damage the tube itself. In this way a blood clot, for example, is easily lasered, and fibrin or vitreous can sometimes be lasered with the YAG.

“In the case of a blood clot, you may also be able to inject tissue plasminogen activator into the anterior chamber to dissolve it,” he notes. “If there’s some bleeding inside the eye after surgery, a clot can sometimes block the tube, at least temporarily. This is usually not a long-term cause of failure, because left alone a clot will eventually dissolve anyway. Vitreous and iris, of course, won’t dissolve on their own; the laser is the easiest way to attempt to clear those blockages.

“In any case, clearing the blockage will often restore functioning,” he says. “At least in the short term, this can often solve the problem and get the pressure back down; usually you’ll see an immediate pressure reduction. However, there’s still a risk of the tube getting blocked again in the same way if you don’t resolve the primary problem, or if there’s a lot of inflammation. Any inflammation such as chronic uveitis can cause a lot of synechial formation. When the tube is sitting close to the iris, as the iris is pulled forward by the synechiae it starts to engulf the tube, eventually blocking it. If you catch this early enough you can sometimes poke a hole through the iris with the laser to restore the flow through the tube. Unfortunately, in most cases that’s only a temporary solution; the continued inflammation will cause the iris to close up on the tube again.”

Dr. Fechter says he hasn’t had much trouble with tubes being blocked by iris. “I create an anterior bevel to keep the tube opening away from the iris,” he explains. “If you put the tube posteriorly and the tube does become occluded with iris, you can punch a hole in the iris with the laser and allow the tube tip to extend through the iridotomy.

“Tube occlusion by vitreous should be prevented by performing a vitrectomy to remove any vitreous that has made its way into the anterior chamber,” he adds. “If vitreous does manage to clog the tube, the YAG laser probably will not help. The best approach is to perform a vitrectomy to remove the source of the obstruction.”

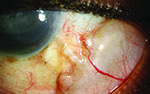

Preventing Tube Exposure

“Exposure is a common issue with tubes, usually due to the upper eyelid eroding the conjunctiva overlying the tube,” notes Dr. WuDunn.

|

He admits that resolving this problem can be tricky. “There are different approaches, and no matter what you do it often recurs,” he says. “You think you’ve closed the conjunctiva with a couple of sutures; but you haven’t addressed the real problem—the eyelid rubbing against it where it overlies this elevated foreign body. Closing it with sutures will work temporarily; but after a few months it may wear down again, leaving the tube exposed.”

One common strategy for addressing this concern is to place a patch graft over the tube. “There’s a lot of debate about how best to use patch grafts,” notes Dr. WuDunn. “The idea of putting a graft on the tube is that you don’t want the conjunctiva to be sitting right on top of the tube, because when the lid comes down over the conjunctiva it’s going to rub against the tube, leading to exposure. The thought is that if you cover the tube with a graft, that will spread out the elevation over a broader area so you’re less likely to get erosion.”

Dr. WuDunn points out that a pericardium graft is often chosen because it’s pretty thin. “Scleral grafts tend to be a little thicker and more expensive,” he says. “The third option is cornea, and that’s now coming into vogue because it’s clear. You can see the tube all the way along its length; if there’s a blockage, you can see where it is. This can also help if you’ve tied an absorbable suture around the tube. If you need to cut the suture early—say the pressure is really high after three weeks and you want the pressure to be down now, instead of waiting five weeks for the ligature to absorb—you can go ahead and laser it with an argon laser, because you can see where the ligature is through the clear graft.”

Changing Tube Placement

Another approach that attempts to minimize this problem involves placing the tube differently. Dr. Freedman says that Dr. Molteno’s original approach to managing this concern was to do a lamellar scleral flap and bury the tube under the flap before it went into the eye. “I did that for a number of years, but it became clear that because the path was lamellar rather than full thickness, the tube would erode,” he says. “Furthermore, tying the flap down posteriorly caused the tube to come up inside the eye and touch the corneal endothelium. So I began putting on a scleral patch.4

“Many other patches have been developed subsequently,” he adds. “The problem has been that there is still erosion because the tube is curved. The curve of the tube produces pressure on the undersurface of the flap, and that can also lead to erosion. As a result, many surgeons today put the tube through a scleral tunnel instead of directly into the anterior chamber; they then cover that with a patch as well. This has decreased the curvature of the tube and made it flatter, so the erosion problem is not as frequent as it used to be.” (Dr. WuDunn notes that some surgeons who make a long tunnel through the patient’s sclera do not put a graft on top, in an attempt to reduce overall elevation and potentially reduce the likelihood of tube erosion.)

Another approach involves changing the location at which the tube enters the eye. “Many surgeons direct the tube along a straight course from the plate to the anterior chamber,” notes Dr. Fechter. “Dr. Paul Palmberg at Bascom Palmer initially trained me to direct the tube more toward the 12 o’clock position, to allow for lid coverage of the course of the tube. I believe this helps to prevent tube erosion.

“I think it’s extremely important to route the tube this way,” he continues. “Most tube erosions occur where the eyelid crosses over the tube at the 2 and 10 o’clock positions; all the erosions I’ve seen in referred patients were in that region. So, if you never put your tube in that region to begin with, it greatly reduces the chance of erosion. I also pass the 23-ga. needle about 3 to 4 mm from the limbus, near the 12 o’clock position, so the tube is protected by the upper eyelid. The conjunctiva covering the tube is well-protected, and you don’t get constant rubbing of the eyelid margin over the tube. There may be some patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis with scleral melt that you really can’t help anyway, but I’ve been using this technique for more than 10 years and my patients have had a very low incidence of tube or plate erosion.

“I also make my tube entry into the eye more distal to the limbus than many surgeons,” he says. “I use the long scleral tunnel technique described by Felix Gil Carrasco, MD. Dr. Carrasco showed that in a large series of Ahmed implants using long scleral tunnels without any patch grafts there was a low incidence of tube erosion. When I heard that Medicare had stopped paying for patch grafts in conjunction with tube surgery, I thought that surgeons would stop using patch grafts over tubes, due to Dr. Carrasco’s success. However, due to subsequent negotiations, glaucoma surgeons can now get reimbursed by Medicare for corneal patch graft material. As a result, I think that many surgeons will switch from their current patch graft material to cornea patches, if they continue to cover their tubes.”

Dr. Fechter admits that the long scleral tunnel approach is not totally risk-free. “The potential complication with this technique is that the tube tends to be more posterior,” he says. “As a result, there’s not only an increased risk of hyphema, but also an increased risk of the tube causing pupil peaking. The peaked pupil, however, is more of a cosmetic concern than a major complication.

|

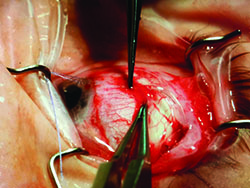

A Supra-Tenon’s Pocket

Dr. Freedman has developed another effective way to minimize tube exposure, one that appears to be gaining popularity. “In this approach I place the implant in a supra-Tenon’s pocket,” he explains. “Most surgeons put the implant under both the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule. However, it was shown some years ago that Tenon’s capsule contains the messenger RNA for TGFb-2. In fact, it’s a major producer of TGFb-2, and that’s what triggers all the fibrosis.

“Back in the 1990s it occurred to me to make a pocket for the implant within Tenon’s instead of placing it underneath Tenon’s,” he continues. “This approach has been published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology and Archives of Ophthalmology.5,6 We compared the two approaches in a group of African Americans with aggressive disease. The data clearly showed that the supra-Tenon’s method eliminates about half of the Tenon’s capsule from participating in the final bleb, resulting in a thinner bleb capsule. The assumption is that we are eliminating some of the TGFb-2 and thereby decreasing the fibrotic potential of the bleb; as a result, we get much better blebs. Other surgeons are now trying this technique, but many of them are simply putting the devices under the conjunctiva, not in a Tenon’s pocket; this variation could make the potential for conjunctival erosion much higher. I would suggest that eliminating Tenon’s entirely is ill-advised.

“Based on this concept, I convinced the Moltenos to develop a new Molteno implant, the M3S, which is now on the market,” he adds. “This version is much easier to use and can be implanted in a supra-Tenon’s pocket without fear of conjunctival erosion.”

Managing a Second Tube

Given that tubes may fail after a period of time, surgeons are occasionally faced with deciding what to do next. Dr. WuDunn notes that because there’s only about a 40 percent success rate when rescuing a failed tube, many surgeons just put in a second tube in a different place. “I don’t advocate revising a tube shunt, although some surgeons do,” he says. “I think if you’re taking the patient to the operating room, you might as well put a second tube in there. You could do both—put in a second tube and revise the first. That might work OK. But you’re probably going to get the most bang for your buck from the second tube.

“Second tubes generally work very well,” he continues. “They do about as well as the first implant, so you can get another four to seven years of good pressure control. That may not seem like a lot, but by the time you get to the second tube, these patients have already had a trabeculectomy and the first tube shunt. They tend to be more advanced, complicated cases than the primary surgeries. These are the cases that haven’t gone well with other surgeries.”

|

“Tube positioning is also very important,” he continues. “The first tube should be placed supratemporally, the second inferonasally. An inferior-temporal tube often provides a poor cosmetic result and may increase the risk of tube and plate exposure.”

Dr. WuDunn adds that there are alternatives to placing a second tube shunt. “My preference would be to do the second tube; but sometimes there may be some reason I don’t want to put in a second tube,” he says. “Perhaps there’s so much scar tissue that I don’t think I can get a second tube in there, or the patient may already have two failed tubes and we’re looking at a third. I have put third ones in, but the success rate is definitely not as good as that of the primary tubes. One alternative is laser cyclophotocoagulation, either with endolaser or from an external approach. This can sometimes be done in the office. It also might be feasible to try one of the new MIGS procedures. Whether they would work in this situation is not known, but one could try a Trabectome or iStent procedure to see if that would help drain fluid through the regular outflow pathway. You might need to put in several iStents, of course. The good thing is that having tubes in place doesn’t prevent you from trying one of these angle surgeries.”

What About the First Shunt?

Implanting a second shunt raises the question of what to do—if anything—with the first implant. Dr. Fechter says he usually leaves the first implant as it is. “It’s probably contributing somewhat to pressure control,” he notes. However, if I think the first tube has failed I’d either revise it or remove it surgically. Another option is to replace the first implant with a different one. On three occasions I removed an Ahmed implant that failed due to a thick, fibrosed capsule and replaced it with a Baerveldt implant in the same quadrant. This approach produced good results in younger patients, while reserving the inferotemporal quadrant for possible future surgery.”

“Some people advocate removing the first tube when putting in the second one,” says Dr. WuDunn. “Considering the extra hardware you’re going to put on the eye, you’re potentially going to create some problems with motility. So, if the first one’s not working, you might as well take it out and not have to deal with it. Of course, you have to put the second tube at a different location because there will be a lot of scar tissue where the first tube was located.

“However, removing the first tube will be tricky, because it’s not just a matter of taking the tube out of the eye and pulling out the implant,” he continues. “The implant becomes very adherent to the globe, for two reasons: First, if it’s a Baerveldt implant, it’s usually placed beneath the muscles. The second, bigger problem is that all of these implants have little holes in them to allow scar tissue to create little rivets through the holes. In the old days, before the implants had these little holes, the fluid would flow through the tube into the reservoir and create a very large and elevated bleb that caused motility problems. Allowing scar tissue to form through these holes tacks down the device and the bleb, limiting the elevation that the bleb develops over time.

“Unfortunately, when you try to remove the tube you have to cut each one of those scar rivets that have formed through the holes that are anchoring the implant to the globe,” he says. “The Baerveldt has four holes, and they’re pretty far back, and they’re pretty wide and close to the muscle. That makes it a little tricky to remove the big Baerveldts. The Ahmeds only have two holes, and they’re near the middle of the tube, so that’s not quite as hard.”

Dr. Freedman’s study of the connection between fibrosis and elevated cytokine levels—resulting from elevated pressure—has led him to come up with a novel approach to managing this situation. He has observed that leaving the first, failed implant in the eye often results in rapid failure of the second implant, and he believes that this may be because the failed implant becomes a factory for the production of cytokines. “That’s a big problem, because the aqueous goes in and out of the shunts with the pumping of the heart,” he notes. “That’s true of all the shunts [even those with a valve]. Thanks to the two-way flow and the failed bleb essentially becoming a factory for making cytokines, those cytokines will make their way into the aqueous and then into the second implant, causing it to fibrose.

“Knowing this, I’ve begun trying a new approach,” he says. “Instead of removing the failed implant, I pull out its tube and tie it off using a 7-0 prolene suture. Then I insert it back into the eye. It takes three or four weeks for the prolene to loosen itself, allowing the bleb to work again. We’ve found that during this period of time the failed bleb loses its potential as a factory for producing TGFb-2, and as long as the pressure remains low, it doesn’t regain it. So once the suture releases, the bleb is exchanging fluid with the eye again, but it’s no longer encouraging the fibrotic process. The end result is that you’re left with two functioning blebs, providing a double pressure-reducing effect. We’re conducting an ongoing study to demonstrate this.”

Other Complications

Dr. Fechter offers suggestions for other complications that can sometimes arise:

• Hyphema. Dr. Fechter says that currently, one of the most common complications he encounters with tube surgeries is a mild hyphema, which he attributes to his technique. “I make long scleral tunnels and try to get my tube as far posterior as possible, away from the cornea,” he says.

|

• Diplopia. Dr. Fechter says he hasn’t had much trouble with this issue, unlike some other surgeons. “I think that has to do with clearing a space for the implant to fit beneath the muscles,” he says. “You have to clear the Tenon’s attachment to the lateral borders of the muscles. When I do that I find I can slip the implant in without much resistance and suture it posterior to the muscles by at least a millimeter. Since using this technique I’ve seen a reduction in diplopia.

“The one patient group in which I still see diplopia is my African-American patients with thick Tenon’s capsules,” he adds. “They can form large, exuberant blebs during the healing process, and the pressure of that bleb pushing against the globe can lead to diplopia. Fortunately, the diplopia usually resolves on its own; there was only one instance in which I had to reoperate to fix the diplopia.”

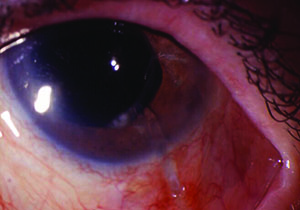

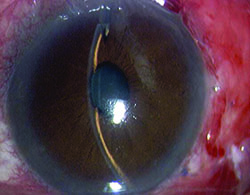

• Bullous keratopathy. “Bullous keratopathy is often due to corneal endothelial damage in patients who have been on chronic glaucoma therapy,” Dr. Fechter explains. ”They have compromised epithelium from long-term medication use and also compromised endothelium from years of elevated pressure.

“Many surgeons believe that the tube itself causes endothelial cell loss,” he continues. “I believe that if you can place the tube behind Schwalbe’s line, you may decrease the chance of endothelial cell loss. Some surgeons will put the tube behind the iris in pseudophakic eyes. I will do that on occasion, but that has its own set of complications; sometimes the pressure is elevated and you’re not sure why and you can’t see the tube. So my preference is to place the tube anterior to the iris but as close to the iris as possible, not touching the cornea, and behind Schwalbe’s line. If the patient has iris neovascularization or chronic angle closure with peripheral anterior synechiae, then I’ll place the tube through a prior peripheral iridotomy or direct it behind the iris with the tube tip extending up to the pupil border.”

• Choroidal effusions. “Choroidal effusions can be an issue when the tube opens,” Dr. Fechter notes. “I’d say one out of 20 patients will experience noticeable hypotony when the tube opens, and there is some choroidal effusion and shallowing of the anterior chamber. If the hypotony persists, I treat it with viscoelastic injected into the anterior chamber. The only time I drain a choroidal is if it’s long-standing, in which case I’m worried about hypotony maculopathy or choroidal touch. I rarely need to drain choroidals—maybe once every three or four years, and I put in more than 100 tubes a year.”

Surgical Pearls

Drs. Fechter and WuDunn offer these additional strategies to help improve outcomes:

• Leave extra tube length. “If you think you may need to revise the tube later, it’s important to allow extra length,” says Dr. WuDunn. “If the tube gets moved out of position or you find it’s blocked by iris tissue, you may need to move the tube to a different location. That means you need to leave a little extra length on the tube during your initial procedure.

“One good way to do that is to curve it around a little to the left or right before it goes into the eye,” he notes. “You want to keep the amount of tube inside the eye fairly limited, because the longer your tube is, the more likely you’re going to damage the cornea. Every time you blink, the eyelid pushes the cornea backwards a little bit, so if the tube is very close to the cornea it will touch or push on the tube, and that can lead to corneal edema. This means you need to leave any extra length outside, along the sclera.”

• Don’t pass your sutures too deep in the sclera. “There’s a possibility of retinal detachment if you do this,” says Dr. Fechter. “One of the few times I’ve seen it happen was in a nanophthalmic eye, when we were performing a vitrectomy in addition to the Baerveldt surgery. The retina surgeon made the incisions through the pars plana—and in a nanophthalmic eye there is a smaller-than-usual pars plana. We inadvertently created a retinal detachment while preparing to insert the tube posteriorly. Fortunately, retinal detachments are a rare complication during normal tube surgery.”

• Consider using only one suture. “One thing I do differently from some glaucoma surgeons is that I only use one vicryl suture for my entire case,” says Dr. Fechter. “The single vicryl suture acts as a traction suture, secures the plate and patch graft to the sclera, ligates the tube and closes the conjunctiva. I know that some surgeons also place an additional prolene suture in the lumen of the tube to help control the pressure during the early postoperative period. I’m glad that the prolene suture works for them, but my patients do quite well with just the single vicryl ligature that dissolves five weeks after surgery. My technique requires less OR time, is less expensive and eliminates the need to manually remove the prolene stent in the office.”

• Be careful with uveitic patients. “Uveitic patients are perhaps the most difficult glaucoma patients to manage because their pressure is either too high or too low and it’s very difficult to keep it just right,” notes Dr. Fechter. “With these patients, it’s extremely important to keep the inflammation under control and to seek the assistance of a rheumatologist or a uveitis specialist. By doing so, you can prevent the eye from becoming hypotonous as a result of aqueous hyposecretion.”

• Mitomycin is probably not worth using. “There was some thought that using mitomycin-C might decrease the amount of scar tissue that forms around the reservoir, reducing the thickness of the capsule,” notes Dr. WuDunn. “Only a couple of sites have tried this, and they were very small studies; they didn’t appear to show any advantage to using mitomycin. It may be that when you’re talking about a foreign body such as an implant, it’s just too hard to prevent scar tissue from forming around it. So unless you’re using really high does of mitomycin—and I don’t think anyone’s tried higher than 0.5 mg—scar tissue forms no matter what. Much higher doses of mitomycin might prevent that, but that would increase the risk of the implant extruding or getting exposed because of the loss of scar tissue around it.”

• Learn by observation. Dr. Fechter notes that the best way to learn good technique is by observing others with more experience. “Find out which surgeons in your community have put in a lot of tubes and ask to observe them in the OR,” he says. “During my fellowship I had the opportunity to observe several excellent glaucoma surgeons implanting tubes. I took what I thought was the best from each surgeon’s technique and incorporated it into my own.”

• If you do have a complication, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Dr. Fechter notes that there’s no shame in asking for advice from someone who has done more cases than you. “Many glaucoma surgeons contribute to glaucoma forums on the Web and discuss their complications and problems with other glaucoma surgeons,” he says. “Oftentimes another surgeon has had the complication you’re faced with and can offer advice on how to fix it.” REVIEW

1. Chen PP, Palmberg PF. Needling revision of glaucoma drainage device filtering blebs. Ophthalmology 1997;104:6:1004-10.

2. Nour-Mahdavi K, Caprioli J. Evaluation of the hypertensive phase after insertion of the Ahmed glaucoma valve. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:1001-8.

3. Pakravan M, Sharam SR, Shahin Y et al. Effect of early treatment with aqueous suppressants on Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation outcomes. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1693-98.

4. Freedman J. Scleral patch grafts with Molteno setons. Ophthalmic Surgery 1987;18:7:532-4.

5. Freedman J, Chamnongvonse P. Supra-Tenon’s placement of a single-plate Molteno implant. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:669-72.

6. Freedman J, Bhandari R. Supra-tenon capsule placement of original Molteno vs. Molteno 3 tube implants in black patients with refractory glaucoma: a single-surgeon experience. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:8:993-7.