Treatment typically consists of antiviral therapy and needs to be initiated immediately. According to Elisabeth J. Cohen, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the NYU Langone Medical Center, the recommended treatment is Valtrex 1,000 mg three times a day for a week or Famvir 500 mg three times a day for a week. “The key thing is that treatment should begin within 72 hours of the onset of the rash. That’s how it was studied, and that’s how it is approved and recommended. You need to use the correct dose, which is higher than the dose used for herpes simplex infections,” she says.

Even with prompt antiviral treatment, some patients develop painful neuralgias, which can be difficult to treat. These neuralgias are not so much from the acute viral infection, but from the inflammation that the virus elicits along with damage to sensory nerves, Dr. Pepose explains. According to him, treatment in these cases can include gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants. “Additionally, people have tried lidocaine patches and capsaicin to treat the pain,” he explains.

Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

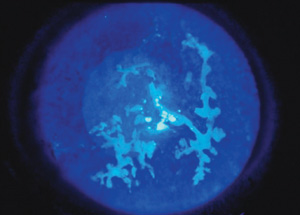

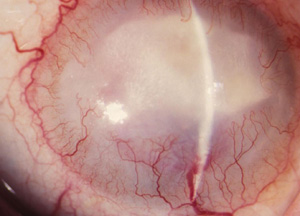

According to Thomas Liesegang, MD, who is in practice at the Mayo Clinic in Florida, ophthalmologists see the worst cases of zoster. “We see more complicated cases on the surface of the eye, on the surface of the skin and on the surface of the conjunctiva, but it also can manifest itself intraocularly. There can be inflammation within the retina and the optic nerve. It can cause blindness and affect the motility or movement of the eye, and it can lead to paralysis and proptosis. It can also get into the brain, which increases the incidence of stroke. The virus can get into the vessels within the brain and can cause an inflammatory reaction,” he says.

|

Dr. Cohen knows this all too well. She contracted herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which caused her to lose vision and have to give up cornea surgery. “I have a friend in whom it spread to her spinal cord, and she has involvement of her legs,” she says. “Of the people who get herpes zoster in cranial nerve 5, division 1, half will have it in their eye, and about 30 percent will end up with chronic eye disease.”

She is currently working on a randomized clinical trial looking at a year of suppressive antiviral treatment compared with placebo in people with herpes zoster ophthalmicus to try to reduce complications of eye disease and recurrent eye inflammation, as well as a post-herpetic neuralgia. “This approach was highly effective in herpes simplex eye disease, says Dr. Cohen. “We now know that many of the complications of herpes zoster are related to chronic active infection after an episode of shingles. It makes a lot of sense to evaluate chronic suppressive treatment in addition to the acute recommended treatment for a week. We are applying to the [National Eye Institute] for a trial to study it in people who either have zoster in their eye of recent onset or chronic disease with a recent episode. We are looking at people who are younger than 60 years compared to 60 years or older at the onset of zoster, because the disease is a little different in the younger and older groups.”

Herpes Zoster Vaccine

Because herpes zoster can have such severe complications, prevention is better than treatment. Dr. Cohen notes that the herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) is currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention for people who are 60 and older, where it has an efficacy of 50 percent in preventing shingles, and 66 percent in reducing the severity of post-herpetic neuralgia.1 “Additionally, it is [Food and Drug Administration]-approved for people aged 50 to 59 years, where it is almost 70 percent effective at reducing the incidence of shingles. Unfortunately, the CDC has not extended its recommendations to people in their 50s, I think erroneously, because they are concerned about the cost of immunizing a lot of these people, and they don’t think it’s as cost-effective because people in their 50s are not as prone to post-herpetic neuralgia. In addition, they are concerned about the duration of the efficacy of the vaccine,” she says.

According to Dr. Pepose, the availability of Zostavax has not yet markedly decreased the incidence of herpes zoster. “We have been surprised that many non-immunosuppressed people who are eligible candidates for the vaccine really haven’t been vaccinated,” he says.

A recent study found that prevention modalities, such as the vaccine and long-term oral antiviral therapy to reduce ocular herpes zoster infection recurrence, are underused.2 The study was conducted to assess the spectrum of disease and treatment among patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus and herpes simplex virus infection. The study included 64 patients (40 with herpes zoster ophthalmicus and 24 with ocular herpes simplex infection). Patients with herpes zoster were older (mean age: 51 ±15 years) than those with herpes simplex (mean age: 33 ±16 years).

In this study, 73 percent of patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus were younger than 60 years, and of these patients, 90 percent were immunocompetent. The most common decade of onset was during patients’ 50s. The study included 12 patients who were eligible to receive the herpes zoster vaccine, but none of these patients had received the vaccine. Twenty-four patients had ocular herpes simplex virus infection, and of these, seven patients had corneal stromal disease and 10 had infectious epithelial keratitis. None of the patients in this study were treated with long-term oral antiviral prophylaxis.

“People think it is a disease of old folks, but the average onset of disease in the United States is 52 years. At least half of all cases occur in people younger than age 60, and more than 90 percent of people who get shingles have healthy immune systems and are not sick. This disease has life-altering and life-threatening consequences, including strokes,” says Dr. Cohen.

In one retrospective study assessing the link between herpes zoster ophthalmicus and subsequent stroke, patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus had a 4.5 times higher risk of stroke than the control group.3

|

Dr. Cohen notes that, while a booster would raise the cost of preventing the disease—if in the future it becomes recommended—we should look at the cost of the disease and not the cost of the vaccine. According to her, at least $1 billion a year is spent on this disease. “We in the United States may underestimate the burden of this disease because it’s very difficult to gather the data,” she says.

Dr. Liesegang agrees: “The cost of treating zoster is great, he says. “The virus can cause post-herpetic neuralgia and depression. There are many other complications of herpes zoster, which may be more of a financial and medical burden to care for. The question is whether we are shifting the incidence from chicken pox to zoster and whether this is good or bad. Other countries have looked at these data and have decided that the potential increase in zoster in the elderly is one of the reasons why they don’t routinely recommend the chicken pox vaccine.”

Questions remain about the effect of the chicken pox vaccine on children as they age, as well as on the elderly population who have not had the chicken pox vaccine and who are no longer exposed to chicken pox later in life. “The theory is that, the older you get, your cellular immunity dwindles and so you are more likely to reactivate the zoster that you got as a kid when you had chicken pox,” Dr. Pepose says. “Young people now get vaccinated for chicken pox with Varivax, which uses an attenuated strain of varicella. We don’t know what effect this varicella vaccine will have many years from now with respect to reactivation as zoster when these children are 50 or 60 or older.”

In addition to children not being exposed to chicken pox in the community, older adults are also no longer being exposed to wild-type chicken pox virus. “Previously, when you were 50 to 60 years old, you were occasionally exposed to chicken pox when visiting someone’s child,” Dr. Pepose says. “Now, young people don’t get chicken pox very frequently because they are vaccinated, so older people don’t get that periodic boost in their immune systems by coming in contact with chicken pox. The herpes zoster vaccine may be more important now than it was prior to the varicella vaccine being offered to children.”

Dr. Liesegang points out that there was a concept, which is still held today, that if a grandmother is in the household of a child with chicken pox, the exposure to chicken pox boosts the grandmother’s immune system and protects her against zoster. “If you do away with chicken pox by giving a vaccine, the whole elderly population will no longer be exposed to chicken pox,” he says. ‘Whether their zoster immune response will decline even faster is a question that we have had for 20 years.”

He adds that the incidence of herpes zoster in developed countries has been increasing, but the increase started before the introduction of the varicella vaccine, and there has not been a dramatic increase since universal chicken pox vaccination.

Dr. Liesegang recommends the zoster vaccine, but notes that there are some cost considerations. “It is not covered under Medicare part B, which is where vaccinations are usually covered,” he says. “The vaccine has only gotten to about 10 percent to 15 percent of the population for whom it is recommended. Additionally, the vaccine is not easy to store. It has to be stored frozen and thawed. It cannot be re-frozen, so you must have several patients lined up, and it is not convenient for physicians to store in the office.”

He explains that family physicians tend to see the milder cases of zoster, and they are the ones who are recommending or giving the vaccinations. “They tend to think of zoster as a milder disease and are not as ready to recommend the vaccine as people who see the bad complications of zoster, such as infectious disease experts and ophthalmologists. Patients don’t consider zoster a bad disease until they get it,” he says. REVIEW

1. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, Bialek SR; Division of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014 Aug 22;63(33):729-31.

2. Edell AR, Cohen EJ. Herpes simplex and herpes zoster eye disease: presentation and management at a city hospital for the underserved in the United States. Eye Contact Lens 2013;39(4):311-314.

3. Grose C, Adams HP. Reassessing the link between herpes zoster ophthalmicus and stroke. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;12(5):527-530.