The Theory

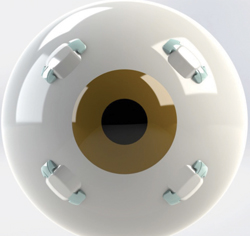

The PresView procedure involves inserting four plastic segments into the sclera between the ocular muscles. The idea behind this is based on a theory of loss of accommodation proposed by Texas surgeon Ronald Schachar back in the 1990s. In a nutshell, Dr. Schachar proposed that we lose the ability to accommodate because the crystalline lens gradually gets larger over time, eventually crowding the zonules so they’re no longer taut and able to exert force on the lens to get it to change shape and allow accommodation. The intrascleral segments are supposed to act like a kind of spacer, pulling the sclera away from the lens, tightening the zonules and allowing them to aid accommodation.

The problem is, not everyone agrees with this relatively new take on presbyopia’s mechanism. “I think the theory may have some merit, but it’s never been proven that that’s the mechanism that’s occurring in presbyopia,” says Keith Walter, MD, associate professor of surgical sciences-ophthalmology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Dr. Walter debated the merits of presbyopic treatments, one of which was scleral expansion, at the 2014 meeting of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery’s Cornea Day. “Part of the problem with scleral expansion is we’re not sure of the science behind it, how the science explains it’s going to work or what magnitude of accommodation we’re going to get.”

|

Dr. Walter says if it does work, the accommodation restored by it has been low. “I haven’t seen any studies yet that show that the patient gets more than 1 D or so,” he says. “I haven’t done any myself, but I’ve seen some patients who’ve had it, and they do seem happy. But I think it has that limitation that we don’t really know how it works.”

Scleral Expansion Today

Nashville, Tenn., anterior segment surgeon and PresView investigator Ming Wang says that, when it comes to the debate about the basis for scleral expansion’s mechanism of action, both sides may be right. “There is a linear relationship between a patient’s age and his amount of presbyopia,” he says. “That’s why a doctor could recommend a reading add for a presbyope over the phone after just hearing her age. However, a doctor can’t recommend cataract surgery over the phone based on age. This means that lens rigidity and presbyopia aren’t linear with each other. So, there’s something in addition to lens rigidity that causes one to lose accommodation or the ability to focus at near. Perhaps the Helmholtz theory only explains half the story.” Dr. Wang says the enlargement of the crystalline lens is the other part. “The spacing procedure only addresses this second half,” Dr. Wang says. “It’s doesn’t even pretend to solve the entirety of the problem. It only solves the problem of crowding from the growing lens and the loss of zonular tension.”

|

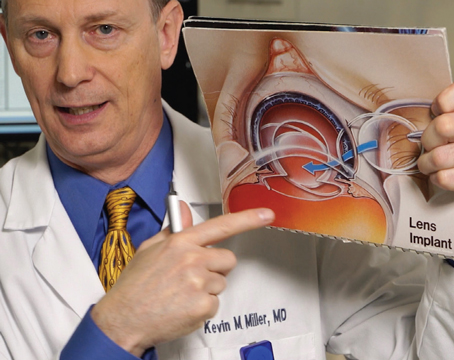

In the current iteration of the procedure used in the FDA trial, the surgeon uses a device to create a tunnel approximately 4-mm long, into which it deposits the segment. Then, a locking spacer is placed on one end of the segment to prevent it from migrating back into the tunnel. Currently, the trial has treated its requisite 330 patients, and Dr. Wang says it’s now in a two-year period in which the FDA wants to monitor the patients. “At our practice, which is one of the FDA study sites, we achieved about 1.25 D of accommodation,” Dr. Wang says. “This is what you’d anticipate achieving in a patient 60 years old or so who has about 2.25 D of presbyopia. We address about half of the problem.” Though potential problems include erosion of the tissue above the segment and segment migration, Dr. Wang says his patients haven’t experienced any serious complications.

Lingering Issues

Dr. Walter says that even if the procedure works as it’s proposed, he wonders if there might be easier approaches for presbyopia. “When I and other doctors look at it, we say to ourselves, ‘That looks like a lot of trouble to insert four segments,’ though I must admit they’ve got the procedure down to a very elegant method,” he says. “The way they go in the tunnel and then lock the pieces together is very nice. But you’re going to have pain with that, so a surgeon would wonder if he needs a nerve block. If I were to put investigative presbyopia treatments on a scale from easy to hard, the Kamra inlay would be easier for a surgeon, especially if he were already doing LASIK. Presby-LASIK, IntraCor [with the femtosecond] or some other multifocal ablation would be easy, especially if you could just use one treatment card. Scleral expansion seems like it would be on the other end of the scale where it would be challenging to do in the office. You’d have to deal with placing them precisely, as well as any hemorrhage and patient satisfaction issues involved with pain and recovery.” REVIEW

Neither Dr. Walter nor Dr. Wang has a financial interest in any product or company mentioned in the article.

1. Glasser A, Kaufman PL. The mechanism of accommodation in primates. Ophthalmology 1999;106:5:863-72.

2. Glasser A. Restoration of accommodation: Surgical options for correction of presbyopia. Clin Exp Optom 2008;91:3:279–295.

3. Mathews S. Scleral expansion surgery does not restore accommodation in human presbyopia. Ophthalmology 1999;106:5:873-7.

4. Ostrin LA, Kasthurirangan S, Glasser A. Evaluation of a satisfied bilateral scleral expansion band patient. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004;30:7:1445-53.