Patients at Risk

|

| Epithelial ingrowth that interferes with vision needs to be addressed, say surgeons. |

“Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy will increase the chance of an epithelial irregularity or a defect, and those increase the risk of ingrowth,” explains Christopher Rapuano, MD, director of the cornea service at Philadelphia’s Wills Eye Hospital. “Also, obviously, trauma to the flap increases the risk, whether the trauma is unintended or is caused by a flap-lift enhancement. Some surgeons will perform a diamond-burr polishing or excimer PTK several months before the LASIK in EBMD patients as a preventive measure, just in an attempt to get a healthier epithelium. However, some surgeons will just do PRK in these patients rather than LASIK. In the past, I’ve done the preop diamond-burr polishing technique, and it’s reasonable to do if a patient really wants LASIK. However, even with the diamond burr and the PTK, the epithelium is often not cemented down; it’s good enough that they don’t get symptoms, but when you stress it with a LASIK flap, sometimes it still gets loose.”

The flap-lift enhancement is a particular risk for ingrowth. “In my entire career, I’ve only had one patient who got epithelial ingrowth from a primary LASIK,” says Beverly Hills, Calif., surgeon Andrew Caster. “It’s almost exclusively a complication of a flap-lift enhancement. Also, when doing an enhancement, if a person has blepharitis or meibomian gland dysfunction—in other words, poor tear coverage—those are the ones more likely to get epithelial ingrowth when lifting the flap for an enhancement. If they have ocular surface issues before the flap lift, make sure to get those things quiet beforehand.

“I performed a study quite a few years ago that showed that the three-year mark after the primary LASIK procedure seems to be a dividing line,” Dr. Caster continues. “I found that eyes in which the flap is lifted sooner than three years after the primary LASIK have almost no epithelial ingrowth, and eyes that are three or more years out seem to have about a 7-percent chance of ingrowth.”1 Because of this risk with later enhancements, some surgeons prefer to perform a PRK enhancement rather than relift the flap to perform a LASIK enhancement if it’s been three years since the initial procedure.

Denver surgeon Michael Taravella says you can take steps to prevent ingrowth in certain cases. “I try to carefully check the edge of the flap on freshly created laser flaps, and in cases in which a flap lift is necessary for an enhancement,” he says. “I’ll take a Weck-Cel sponge and gently touch the edge of the flap 360 degrees around, including the hinge area, looking for and removing loose fragments of epithelium, especially on flap-lift cases.” Dr. Caster will treat flap-lift enhancement patients with a longer course of steroids than his primary cases, treating them on a tapering basis for a month postop.

Though it’s not been scientifically proven, a couple of surgeons feel that a hyperopic treatment increases the risk for ingrowth. “It’s my clinical impression that epithelial ingrowth is more common when you’re doing an enhancement that’s going to involve a hyperopic treatment,” Dr. Caster says. “My theory is that with these treatments, you’re applying laser energy farther out, near the edge of the flap, and this may be a predisposing factor.

“There’s something that’s important to note,” he continues. “Before you do a flap-lift enhancement, you need to discuss the risk of epithelial ingrowth with the patient. If it’s been three years since the primary LASIK, I always tell him that there’s a 7-percent risk of getting this problem, and that it can be completely avoided by doing a PRK, but that we’re choosing to do a flap lift because it heals faster. I say we’ll just have to deal with that 7-percent risk of ingrowth. Likewise, if you’re doing an epithelial ingrowth removal, you should discuss with the patient the fact that the ingrowth could recur. It’s important to have the patient onboard before you do these treatments.”

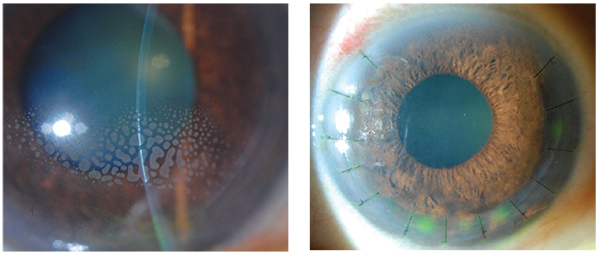

|

| This patient’s epithelial ingrowth was removed initially, but then recurred (left). In response, the surgeon scraped out the cells and then sutured down the flap in an effort to seal down the flap edges and prevent further infiltration of epithelial cells (right). |

There are certain signs and symptoms to watch for when deciding whether it’s time to intervene in a case of epithelial ingrowth, surgeons say.

“Ingrowth affecting the health of the cornea is the number-one indication to remove it,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Basically, if it’s causing pain or a foreign-body sensation, that’s usually because there’s overlying superficial punctate keratitis or an epithelial defect—or stromal melting, which is even worse. Those are indications for removing it. The number-two indication for removal is if it’s distorting the vision. Typically, distortion occurs when the ingrowth is somewhat elevated and is reaching at least a couple of millimeters away from the flap edge toward the center. Usually, if it’s one or two millimeters from the edge it won’t cause a big change in vision, but more than that and it often affects vision. If it’s less than a millimeter away from the edge and even if there’s a very little bit of melting, we won’t intervene; we’ll just use lubrication and observe it.”

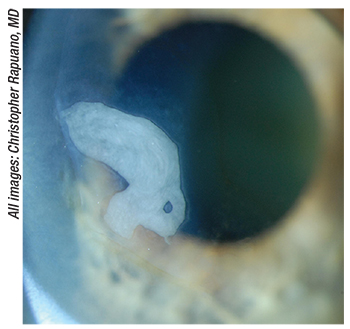

There’s also the type of ingrowth that appears as an island beneath the flap, and doesn’t appear connected to the flap edge. “If this island is more central, it tends to affect vision,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If this is the case then you often need to treat it.” Dr. Taravella says imaging can help in some cases of epithelial islands. “Topography can be a useful tool in assessing whether or not an island of epithelium is distorting the central corneal curvature,” he says, “and it can also be used to follow progression, especially if tomography is available and shows thickening/increased pachymetry in the area of concern.”

Edward Manche, MD, director of cornea and refractive surgery at Stanford University’s Eye Laser Center, says the timing can also be a clue to the severity. “If it’s less than a millimeter from the edge with no elevation, scalloping, staining, fibrosis or topographic changes, and patients are comfortable, it’s something you can just watch,” he says. “Usually, ingrowth will declare itself within three to four weeks after the surgery and then, if it’s going to progress, it will do so after that. So, if I see any progression after that first month, I’ll intervene.”

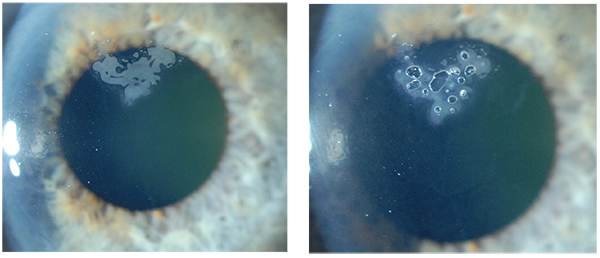

|

| A “semi-surgical” method some surgeons use to treat epithelial ingrowth is YAG laser. Here, a patient’s progressive ingrowth, left, was treated with the YAG. The laser creates bubbles that work to remove the epithelial cells (right). |

Once you’ve made the decision to intervene in a case of epithelial ingrowth, surgeons say you can begin conservatively and then get more aggressive as necessary. Also, some surgeons take slightly different approaches.

“There are two main ways to treat ingrowth,” says Dr. Rapuano. “First, you can lift the flap, scrape it out, and replace the flap. If the ingrowth is just in one quadrant, just lift that quadrant and carefully but aggressively scrape both the bed and the underside of the flap to get the ingrowth out. The underside of the flap is important because often there are a number of epithelial cells there. However, it’s trickier scraping the underside of the flap because it can be difficult to see if there are any epithelial cells left there, and you don’t want to cut or otherwise damage the flap. Some surgeons also use alcohol to make sure they kill all the cells, but, if you do that, be careful because alcohol can damage the cornea.

“The second way to remove the cells is to treat them with a YAG laser,” Dr. Rapuano continues. “You pepper the ingrowth with a series of YAG spots that create air bubbles that can work to get rid of the ingrowth. Sometimes this works well—but sometimes it doesn’t. It’s not a perfect treatment, and it usually takes two to five laser treatments before you get rid of it all. Whichever way I choose to remove the cells, afterward I’ll remove about two millimeters of peripheral epithelium outside the edge of the flap in order to create a larger epithelial defect. The reason for this is I want the flap to have more time to settle before that peripheral epithelium reaches it. Because when the epithelium reaches the flap edge, I want it to grow over the flap rather than underneath it.” Dr. Caster, however, avoids creating this peripheral defect in ingrowth removal cases. “I haven’t tried that method, but it seems that it might increase the inflammation,” he muses. “This might be counterproductive, since you want to make sure you minimize any inflammation during the procedure and do as little manipulation as possible.”

If the ingrowth recurs, surgeons get more aggressive with sealing the flap down after the cells are removed. “If it recurs, I’ll lift the flap again, remove the epithelial ingrowth, and then use fibrin tissue glue to seal the edge of the flap,” says Dr. Manche. “My experience with that approach has been quite good. I’ve done two dozen recurrent erosion cases this way and, of those, only one had another case of recurrent ingrowth. That patient, however, was someone who had epithelial ingrowth under the flap for many years after his LASIK procedure, and had three or four ingrowth removal treatments at other practices before coming to mine. In rare cases that aren’t addressed well with tissue adhesive, we’ll suture the flap. Suturing has been 100-percent successful in my hands.”

Dr. Rapuano skips glue and sutures recurrent ingrowth cases right away. He describes his approach: “I place between six and 14 radial sutures, depending on how much of the flap I need to lift to remove the cells,” he says. “I put the sutures in pretty tight. I’ll take out about half of the sutures at around six weeks, and then remove the rest at 12 weeks.”

Dr. Caster says he sometimes takes a novel approach to recurrent cases of small amounts of ingrowth that were causing some astigmatism. “In those cases, I decided that, rather than try to get rid of the recalcitrant epithelial ingrowth, it was better to do an astigmatic PRK to compensate for astigmatism caused by the ingrowth,” he avers. “The treatment has been successful and the patients who’ve had it have been happy; they kept the little bit of ingrowth that I couldn’t seem to get rid of, and I treated the astigmatism it was causing.

“

If someone were to take this tack, however,” Dr. Caster adds, “it depends entirely on the patient’s best-corrected acuity. So, if the patient has epithelial ingrowth that’s causing astigmatism and you can use trial glasses to get her to 20/20 and she says she likes that vision, then it’s OK to do a PRK to counteract the astigmatism from the ingrowth. Also, this assumes you’ve been observing the patient and the ingrowth seems to be stable. If however, the ingrowth is causing a decrease in best-corrected vision, then, obviously, you need to remove it and not just treat its effects. Typically, its effect depends on how far toward the pupil margin the ingrowth extends, and how many clock hours it involves. If it’s extending into the pupillary area and decreasing best-corrected vision, then you have to remove it.”

1. Caster AI, Friess DW, Schwendeman FJ. Incidence of epithelial ingrowth in primary and retreatment laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2010;36:1:97-101.