Here, three ophthalmologists accustomed to offering multiple services share their experiences and thoughts regarding the future of comprehensive ophthalmology.

Outlook: Negative?

Douglas K. Grayson, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai and medical director of Omni Eye Services of New York and New Jersey, believes the outlook for small, comprehensive practices is not good. “Having a small, general ophthalmology practice is becoming more and more difficult,” he says. “Consider the perspective of younger individuals coming out of residency. They have to manage the overhead and administrative costs of trying to set up a practice that’s compliant with all of the electronic health record guidelines and HIPAA regulations, and they have to get onto insurance panels, which has become particularly oppressive. Even if you have the financial resources to do all of this, the amount of time and work necessary becomes so burdensome that you can’t really practice and take care of patients. As a result, I believe the trend is going to be toward bigger, hospital-based practices, completely devouring the smaller practices and just hiring associates out of residencies and fellowships. Nobody’s going to be out there empire-building. Patients will go to large centers where there are multiple ophthalmologists, and whoever is there that day is who they’ll get to see.

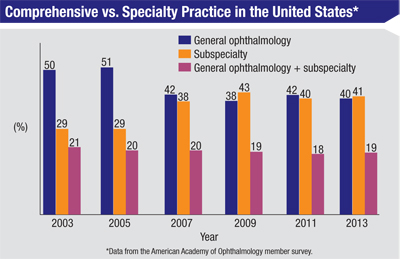

“Twenty years ago,” he continues, “it was fairly common for an ophthalmologist to say, ‘OK, I’m a comprehensive ophthalmologist, I do glaucoma, lids, cataracts, LASIK and I’m running the whole practice myself.’ Bigger groups were less common than the guy offering multiple services. But I think that’s changing. The only way to afford the overhead necessary to manage all the government compliance issues is to be part of a big practice, or a hospital-based practice where they have other sources of revenue to offset any losses they may experience.”

|

“Our practice is currently in the process of acquiring a solo practitioner,” he adds. “He was comprehensive and had a partner. When the partner left, he became a solo guy managing three offices. He was overwhelmed dealing with the records and trying to see all of the patients. He could have tried to bring new people in, but he’s in his 50s and likes doing surgery, so instead we’re acquiring his practice. We’re putting our infrastructure in place, our EMR system, our techs and our scribes. Now all he has to do is show up, see his patients and go home. Before, he was doing a little PRP, glaucoma lasers and cataracts; now he’s just going to do cataracts. And he’s happy. Making the move lifted a tremendous burden from his shoulders.”

Mark H. Blecher, MD, co-director of the cataract department at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia and medical director of the Kremer/TLC laser center in Cherry Hill, N.J., notes that he feels the pressures mounting in his practice. “I’m a comprehensive ophthalmologist in a multi-doctor private practice that’s closely affiliated with Wills Eye Hospital, but not owned or managed by Wills in any way,” he explains. “I think we’re a very progressive and well-managed practice. Nevertheless, the challenge of increasing regulation and pressure from insurance companies is getting to be almost insufferable.

“At the same time, it’s not clear what viable alternatives we have,” he adds. “Are the larger health-care systems interested in ophthalmology? How are they going to provide eye care? Will they subcontract with private practices like mine, or bring things in-house? It’s not clear yet, nor is it clear whether such an offer would be a good option for us. The ground is shifting very substantially at the moment, partly because of the Affordable Care Act and partly because of the ongoing changes in health care that started 30 years ago. I think a lot of us are feeling a lot more pressure and uncertainty than we did in the past.”

On the Other Hand …

Despite the current pressures, many MDs still offer multiple services and are happy to do so. “A lot of the issues surrounding being a general ophthalmologist have to do with when you were trained, how you were trained and where you live—the demographics of your area,” says David Gossage, DO, associate clinical professor of ophthalmology and director of the residency program at Michigan State University. (Dr. Gossage is in private practice in Hillsdale, Mich.) “If you live in a major urban center where you have a retina specialist next door, a glaucoma specialist across the street and a cornea specialist around the corner, you have to ask yourself whether you want to continue to offer those services to your patients. Maybe it would make sense to do only cataract surgery. But if you’re in a rural setting where the closest retina guy is an hour away, the cornea guy is an hour and a half away and a glaucoma specialist is nonexistent, you’re going to have to take care of many more things than you would in that urban setting.”

Dr. Gossage notes that the training a doctor receives makes a difference in how comfortable he or she is offering multiple services. “If you were trained years ago when super-subspecialists were almost nonexistent, you were probably trained to perform many procedures,” he says. “As a result, you may feel very comfortable taking care of multiple problems, problems that doctors who received less-broad training might be more inclined to refer. And of course it makes a difference how well you believe you were trained. I was trained back in the early 90s in pretty much everything from oculoplastics to glaucoma to retina, so I feel comfortable handling many different aspects of comprehensive care.

“Right now I’m living in a rural setting where I do many different procedures and take care of patients with many different pathologies,” he continues. “I know my limitations; if it’s something like a surgical retina case, I’ll send that patient off to a retina specialist. If it’s a surgical cornea case, I’ll send that patient off to a cornea specialist. But for the most part, I do the things I was trained to do. The rest of the services I offer are newer procedures I learned to do as they appeared. For example, when I was in residency, there was no such thing as LASIK, so I had to learn it after residency. Intravitreal injections were not common either, so when that became mainstream I had to learn about it. I continue to stay up-to-date on the studies and current therapies relating to that.”

Dr. Gossage points out that there are some real advantages to being a comprehensive ophthalmologist. “One big advantage is that you’re not put-ting all of your eggs in one basket,” he says. “If your livelihood depends on refractive surgery or LASIK, what happens when all of a sudden a new procedure eliminates the need for your services? What if all you do is cataract surgery and someone invents a drop that gets rid of cataracts? And if you’re very focused on one procedure, what happens if Medicare or other insurance carriers decide to cut the reimbursement for that procedure by 50 percent? It’s really going to take a toll on you. In contrast, if you do a little bit of everything, and you do it well, I think you’re much better off.

“I still do eyelids and blepharoplasty and ptosis repair,” he continues. “I’ll treat squamous and basal cell carcinomas of the face and lids. I still manage pretty much everything except surgical retina or pediatrics (the latter because my wife is a pediatric ophthalmologist, eliminating the need for me to address those cases). At one time I did a lot of LASIK, but right now I don’t because the mobile laser that used to come and support our community is no longer with us. Again, as a comprehensive ophthalmologist, I’m able to take changes like those that have impacted LASIK in stride.

“It’s like the stock market,” he concludes. “You want to be diversified. Being a comprehensive ophthalmologist is like having a balanced portfolio. As long as you maintain good relationships with the super-subspecialists in your area, they can help you when a case goes beyond your skill level. Meanwhile, because you offer a variety of services, you can weather a storm when one arises.”

The Cataract Surgery Factor

Naturally, cataract surgery is a mainstay offering of most general ophthalmologists. However, like many other areas in ophthalmology, this surgery has become increasingly complex, requiring more high-tech equipment and greater skills and precision than ever before. Today, it also requires managing patient expectations that have gone through the roof.

|

"One big advantage [of being a comprehensive ophthalmologist] is that you're not putting all of your eggs in one basket."

–David Gossage, DO |

Dr. Grayson says he currently does glaucoma and cataract surgery; other members of his practice group manage retina, LASIK and plastics services. Today, however, he’s finding that even providing two services is increasingly challenging. “It’s becoming oppressive for me to manage both glaucoma and cataract patients, given the time now that I have to spend with my cataract patients,” he says. “Managing cataract patients used to be very straightforward. Now, patient expectations are much higher, and we have to discuss different lens options and femto vs. non-femto technique. At the end of the day it’s the surgeon who has to talk to the patient about all of this, regardless of how much ancillary education your staff gives the patient. The patient wants to hear what the doctor thinks, and that takes time. Either you end up working until 8:00 at night, or you start seeing fewer patients, which means getting decreased reimbursements.

“Keeping up with the technology is also a problem,” he continues. “For example, it took us a year to integrate femtosecond laser cataract surgery into our practice. Use of the laser is fairly straightforward, but the techniques for taking out the cataract are different, so there’s a learning curve. When you first use the technology, you’re going to have complications, and this is with patients who just paid extra for supposed state-of-the-art cataract surgery. It’s not quite as difficult as the transition from extracap to phaco, but it’s a challenge, and it will add to the burdens already faced by a comprehensive ophthalmologist.

“At first, the slowdown in our practice resulting from this transition was enormous; we were getting home at 10:00 at night from a normal surgery day that used to end at 5:00,” he says. “Eventually we streamlined the process and our techs learned how to dock the patient on the femtosecond laser, but getting there took a long time. Now we’re introducing the ORA instrument, allowing us to do intraoperative IOL power calculation. That’s another whole slowdown that requires more time, focus and energy.”

Dr. Grayson says that one upside of spending more time on cataract patients is that some elements of the surgery are now paid for by the patient out-of-pocket, circumventing the insurance system. “Because of that we can do fewer cases per day and still break even, or stay slightly ahead of where we were when we were doing a lot more cases,” he says. “But at a certain point, when you’ve been in practice a long time, you get into your 50s and you start to get tired. You don’t have the same energy level you had when you were 30. At age 30, staying until midnight wasn’t such a big deal to me. Now, it is. As a result, I’ve decided to narrow my focus to just cataracts. I’m interviewing glaucoma associates now.”

Dr. Gossage acknowledges that cataract patient expectations and the complexity of the surgical options today have increased dramatically, but doesn’t see it as an insurmountable obstacle. “After LASIK became popular in the early 2000s, patients seemed to assume that all eye surgeries should produce equally fast and ideal outcomes,” he notes. “This puts much greater demands on the cataract surgeon. And if you’re committed to being a general ophthalmologist you have to offer toric lenses, limbal relaxing incisions and multifocal lenses, and have the related equipment—topographers and tools such as the IOLMaster or Lenstar. However, you probably don’t have to purchase the most cutting-edge equipment, such as the ORA, which would be a huge practice expense.

“In any case, none of these changes to cataract surgery has undercut my ability to offer multiple services and maintain quality for our patients,” he says. “And if I encounter a complex case that I feel would benefit from the most advanced equipment that’s out there, I still have the option of referring the patient.”

Other Issues

Comprehensive ophthalmologists are subject to a number of other pressures as well:

• It’s hard to do everything well. “If an ophthalmologist is doing a little of everything, he’s not necessarily doing it as well as he could because there’s so much to do,” says Dr. Grayson. “The first patient might be a cataract, the next patient a retina focal laser; he’s got to stay relatively current in a lot of areas. As it is, just staying current in cataract and glaucoma requires a big time commitment. You want to offer the best, state-of-the-art treatments to your patients, and that means attending meetings, taking classes, going to lectures and then integrating the new ideas into your practice. And every new piece of equipment is a challenge. It’s not acceptable to do a little of everything poorly; you have to do everything as well as you can, and that takes time and effort.”

|

“On the other hand, if a patient needs a tube shunt or Molteno, I’d send that patient to a glaucoma specialist because I don’t do enough of them,” he continues. “I wouldn’t try to treat a patient if it’s in his best interests to be sent to a subspecialist. But if I can control the patient’s pathology and disease process while keeping him in the practice, so the patient is comfortable and doesn’t have to travel so far, I think that’s better for the patient. Every day I have patients say they can’t thank me enough for being here. They really do appreciate not having to travel out of the area.”

• Keeping up with the technology can be costly. Dr. Gossage acknowledges that staying truly comprehensive can be a financial burden. “Reimbursements are going down, but you have to keep up with the latest technology, and that’s expensive,” he admits. “If you’re going to continue to do retinal treatment or glaucoma care, you have to be willing to invest in the latest technology, such as OCT, digital fluorescein angiography and software that can help you with things like glaucoma progression analysis. It’s a necessary evil. But I’ve always felt it was worth it, as long as it’s in the best interests of our patients. I’ve always been an early adopter. You have to take the plunge and get the tools you need.”

• Insurance companies are trying to minimize usage. Dr. Blecher notes that insurance companies are adding to the burdens faced by comprehensive ophthalmologists. “Insurers are getting very exclusive and cracking down on their practitioner pools, insisting on precertifications and placing limitations on where you can do your work,” he says. “It’s different in each part of the country, but here in the Northeast insurers are trying to make it more difficult for patients to use their insurance by putting doctors through more hoops to get things approved. For example, a lot of insurance companies are requiring us to call and get a preauthorization for every Avastin or Lucentis injection we do. They can’t tell people not to use their insurance, so they try to make it inconvenient or expensive for either the patient or the practitioner.

“This isn’t a new phenomenon,” he notes. “They’ve been doing variations on this for 30 years; it’s just getting more acute now. A while back, HMOs used to require precertification for everything we did, but they eventually backed off. Today there’s very little competition in the insurance industry, so the companies are feeling that they can be more stringent in their requirements. They’re starting to get very feisty about wanting to control the use of their services.”

• When managing everything, it’s easy to miss something. “The ophthalmologist trying to manage every problem is going to be overwhelmed,” says Dr. Grayson. “Something’s got to give. To offset decreasing reimbursements, you can try to see more patients, but then you’re more likely to miss things. You’ll miss the subtle macular degeneration, you’ll miss the subtle glaucoma. I can’t tell you how many patients I see who have significant glaucoma but were not diagnosed by their general ophthalmologist because the doctor didn‘t look carefully enough at the optic nerve. It’s an every day occurrence.

“Unfortunately,” he adds, “this prob-lem is compounded by some general ophthalmologists not referring patients out in a timely fashion because they think they can do it themselves and they don’t want to lose the patient. The latter problem doesn’t arise in a multispecialty practice; all the issues get taken care of in a timely fashion. Ego and patient protectiveness don’t become part of the equation.”

• Electronic records add to the practitioner’s burden. Dr. Grayson points out that the move to electronic medical records is another time and energy sink that makes it more difficult to stay current with multiple subspecialties. “When we transitioned from paper to electronic records it took us a year and a half to get comfortable dealing with the EHR system,” he notes. “We went live in October of 2012, and it’s just now, two years later, that we’re starting to not have any paper records to manage from patients’ previous visits. It’s a big transition and a big expense.

“Yes, you do get some money back from the government if you meet the meaningful use criteria, but it’s not easy to meet those criteria,” he continues. “Then there are the HIPAA compliance issues. We have a person come in two days a week to make sure our systems are HIPAA-compliant. Then there are all the licensing agreements and all the expenses associated with using the software. Furthermore, we’ve found that you can’t just see a patient on your own with an EHR system—you need a scribe. There’s no way you can turn away from the patient and start typing on the keyboard without depersonalizing the patient-doctor interaction tremendously. And of course, scribes cost money, increasing your overhead.

“The bottom line is that switching to electronic records is another burden, another thing you have to learn to use and maintain,” he says. “If you’re offering multiple services as a comprehensive ophthalmologist, this is yet another set of things you have to deal with.”

|

"To offset decreasing reimbursements, you can try to see more patients, but then you're likely to miss things. You'll miss the subtle macular degeneration, you'll miss the subtle glaucoma."

–Douglas Grayson, MD |

“In some ways, EHR is helpful for a comprehensive ophthalmologist,” he continues. “It makes some things much easier, such as tracking a glaucoma patient’s IOP over time. Now instead of manually charting it, you can just click a button and the chart is there. And the Forum system makes it easy to bring up past and current OCT scans for comparison, without having to use the OCT machine to manipulate the data. But it does slow you down and adds a lot of expense. For a general ophthalmologist I think it’s a mixed blessing.”

• The aging population may make comprehensive ophthalmology even more burdensome. “People are living longer and having more trouble with their eyes,” notes Dr. Grayson. “If you’re comprehensive, and you’re treating macular degeneration in addition to cataracts and glaucoma, that means you’re going to be giving a lot of injections. If the nearest retina specialist is three hours away, then there’s no other choice, but I think that’s a rarity in this country. Managing macular degeneration on top of cataracts and glaucoma is a huge amount of work. The result is that you can’t possibly do it all as well as somebody who just does a single specialty. And you can’t be as current, as state-of-the-art.”

Dr. Gossage sees the aging population more as an issue of being increasingly at the mercy of government regulations and changes. “As general ophthalmologists, we mostly take care of elderly patients because they have the diseases—macular degeneration, cataract and glaucoma,” he says. “And as the number of elderly people in the population increases, so does the proportion of our patients on Medicare. When I first started in practice I was seeing about 65 percent Medicare, maybe 25 or 30 percent commercial insurance patients and 5 percent self-pay. Nowadays my practice is 90 percent Medicare, 5 or 6 percent commercial insurance and 2 or 3 percent self-pay. That’s a big shift toward Medicare patients.

“The problem is that we’re subjected to a lot of pressure because we’re really government employees,” he continues. “The government is our biggest payer. So whatever Medicare does is obviously going to affect our practice reimbursement levels and the way we can practice. For that reason I think the shifting demographics are having a huge impact on our comprehensive practice. Specialists who don’t have a high Medicare volume may not be impacted as much.”

• Referrals may be getting more problematic. Dr. Grayson says another problem faced by comprehensive ophthalmologists is referral sources. “People are usually referred to ophthalmologists by two sources: their regular medical doctor or their optometrist,” he points out. “If the referring medical doctor is part of a large practice or hospital, he’s likely to refer to a specialist who’s part of that group. Optometrists, in my experience, also prefer to refer to specialists. They’re sophisticated enough today to know what the patient’s problem is and what needs to be done. Their view is, why should I send this patient to a guy who does a little cataract, a little retina and a little plastics, when I’ve got access to a cataract specialist, a retina specialist and a plastics specialist? Again, it tends to cut the generalist out of the loop.”

• Patient gratitude may be a decreasing reward. “Medicine is still rewarding, but all of the restrictions and requirements we’re dealing with today take away from the philosophy that was much more dominant 20 years ago,” observes Dr. Grayson. “Back then the idea was, ‘We’re helping people and making a few bucks along the way, and that’s the way it should be.’

“Today it’s about survival,” he says. “And it’s not as easy to work with patients as it used to be. Patient expectation levels are much higher, and often unrealistic. With Internet access, everyone is their own medical advisor, which can become problematic. You get some thank-you’s, but a lot fewer than you did 20 years ago.”

Can Generalists Survive?

Dr. Blecher notes that more and more ophthalmologists—like doctors in general—are starting to think about selling their practices to health-care systems. “Until recently, health-care systems were not very concerned about bringing ophthalmologists onboard,” he says. “That may change going forward. Years ago these kinds of organizations bought up a lot of physician practices, both internists and general practitioners, as a way to control patient flow. Eventually they realized this wasn’t producing the expected result, so they sold a lot of them back off and lost money. But now they’re circling around to doing it again. This time around, physicians—especially in the primary-care field—don’t want to be in practice any more. It’s become too onerous to make a living and have a practice, given all the regulations and shrinking reimbursements they have to deal with. Now they’re more anxious to become part of hospital networks.

“The question is, will this happen to ophthalmology practices?” he continues. “Will we see a trend of ophthalmologists selling their practices to health-care systems, hospitals and accountable care organizations? And if so, what will this mean for our field? Can general ophthalmologists stay in practice under these conditions? And even if they could stay in practice, would they want to?”

Dr. Blecher notes it’s difficult to predict where the pressures on comprehensive ophthalmologists—and the field as a whole—are going to lead. “The situation may slowly evolve, with some ophthalmologists surviving and becoming part of the next version of delivering health care, whatever that turns out to be,” he says. “Or the health care delivery system will hit a crisis and collapse and have to be rebuilt from the ground up. When a system is being pushed so hard from so many directions, it really could collapse, at least in certain areas. I think there’s a chance of that.”

Dr. Grayson believes that if there is a role for the comprehensive ophthalmologist in the future, it won’t be in urban areas. “The only place it makes sense to do a little of everything is in a part of the country where there really are no specialists available,” he says. “Even in that situation, some patients will need to be seen by a specialist, whether it’s convenient or not. So I think there will still be a role for a comprehensive ophthalmologist in this country, but you’ll have to know your limitations. In metropolitan areas, I think the future will be consolidation into large groups, including hospital-based groups.”

Still in the Game

Despite all of the obstacles, Dr. Gossage says he believes there’s still room for a comprehensive ophthalmologist. “I think there’s a lot of pressure to specialize, though,” he says, “including pressure from outside insurance carriers and from some super-subspecialists, saying general ophthalmologists shouldn’t be doing some particular procedure; only they should be offering it. The reality is that traveling an hour and a half to get intravitreal injections is very inconvenient for a lot of elderly patients when those injections can be done locally by a general ophthalmologist such as myself. And I feel perfectly comfortable doing them. I did my first intravitreal injection the day after Macugen became available in 2004. We’d previously been giving steroid injections, so when anti-VEGF injections appeared it made sense for our patients to be locally treated.

“Of course, I do refer to retina specialists,” he adds. “We often share patients. If there’s something that doesn’t seem normal for a specific disease process, I’ll send the patient to the retina specialist. And the retina folks often send patients back to me to continue treatment, because my practice is much closer to the patients and they don’t have to travel so far.”

Despite all the pressures currently affecting comprehensive ophthalmologists, Dr. Gossage is still happy to be in that category. “You have to understand that this is what I wanted to do,” he says. “This is what I love, and I want to continue doing it. Yes, over time it has become harder and more of a burden, but factors such as government reimbursement issues are being addressed every year with the help of advocates from the American Academy of Ophthalmology and other organizations. I used to participate in that myself. So I’m hopeful that many of these issues will be resolved in our favor.” REVIEW