From diagnosis to management to follow-up, inflammatory glaucoma (i.e., uveitic glaucoma) is a challenging entity that tests the clinical skills of even the most experienced glaucoma specialist. There are many causes of the ocular inflammation in these cases, as well as marked difficulties in discerning the relationship between the extent of inflammation and the level of elevated intraocular pressure and/or glaucomatous optic atrophy. Though a single management strategy doesn't apply in all instances, in this article we'll present certain guidelines and highlight particular pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of patients with glaucoma and/or elevated IOP secondary to ocular inflammation.

|

| It's best to perform two iridectomies in a case of a secluded pupil such as this, in case one of the holes closes postoperatively. |

When the physician initially diagnoses a patient as having glaucoma and/or elevated IOP associated with inflammation, he or she should attempt to diagnose the underlying cause of the inflammation. Knowing and understanding the etiology improves the clinician's ability to treat the uveitis more effectively, and this, in turn, helps the management of the elevated IOP in most cases. Since there are many entities that can produce anterior chamber inflammation, it may be prudent to work with a uveitis specialist, internist or rheumatologist to determine the appropriate diagnostic workup. Syphilis, for example, can present as an anterior iritis. Sarcoidosis may appear initially in the eye; as such, the ophthalmologist can greatly aid the internist in the early diagnosis and treatment of this debilitating systemic disease.

A comprehensive ocular and medical history is essential. For instance, if a patient presents with ocular inflammation and the history reveals that he is an avid hiker in the northeastern United States, consider ordering Lyme titers. An accurate determination of the cause of the inflammation can lead to rapid treatment that may limit the clinical course. Accurate diagnosis also helps prevent an unnecessary and prolonged course of steroids and immunosuppressives.

Laboratory tests can also be very helpful in these patients. Although there is no definitive battery of tests that is necessary in all cases, here are several that are particularly useful:

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to detect sarcoidosis, especially if the patient is African American;

• Antinuclear antibodies (ANA);

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate;

• Tuberculosis skin test (since the incidence of tuberculosis is on the rise);

• Chest X-ray (for tuberculosis and sarcoidosis pulmonary involvement);

• Lyme titers (especially in patients from affected areas or who spend a great deal of time outdoors).

The patient's constellation of symptoms and signs can provide clues as to the etiology of the inflammation, as well. For example, granulomas on the lids or conjunctiva may indicate sarcoidosis, while fatigue and body aches suggest Lyme disease.

Glaucoma associated with uveitis can fall into one of three categories: secondary open-angle glaucoma, closed-angle glaucoma or a combination. Secondary open-angle glaucoma may result from inflammatory cells and protein deposits in the trabecular meshwork, trabeculitis or steroid-induced glaucoma. Closed-angle glaucoma can develop from severe ocular inflammation, which can cause either peripheral anterior synechiae and/or posterior synechiae, the latter leading to pupillary block glaucoma and iris bombé.

Patients with glaucoma secondary to uveitis will complain of pain, photophobia, blurry vision and excess tearing. The eyes are usually red.

Treatment

Along with the initiation of a diagnostic workup (where applicable), the clinician should formulate a preliminary diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan. In most cases, topical steroids are appropriate, unless you suspect an infectious etiology. If the subsequent workup yields a different diagnosis, the physician can then alter the treatment plan.

A typical treatment course is topical prednisolone acetate, with a gradual tapering of the drug as the inflammation resolves. The exact regimen will vary based on the severity of the inflammation, but a typical aggressive course of therapy is topical prednisolone acetate dosed every one to two hours while the patient is awake with a return visit within one to four days. If the inflammation flares up as the steroid is subsequently tapered, increase the dosage to previous levels.

In some cases, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent, either administered topically or orally, may be more appropriate than systemic steroid therapy, since NSAIDs avoid steroid-associated side effects such as psychosis, weight gain, osteopenia and ulcers. NSAIDs are often advisable in very young patients, in whom steroids can stunt growth or cause other long-term health problems. If the NSAIDs aren't effective, the clinician can always initiate steroid therapy.

In patients with severe ocular pain and photophobia, topical cycloplegic agents can improve comfort by easing the muscle spasm of the iris and ciliary body. The extent of the patient's photophobia at follow-up visits can also be helpful in gauging the effectiveness of medical therapy.

Of course, one must keep in mind that ocular inflammation may be due to an infectious etiology, in which steroids or NSAIDS are not the appropriate initial agents. This is one of the challenging points of managing uveitis. If the initial evaluation and/or eventual workup points to infection as the cause, place the patient on an aggressive course of antibiotics, with inflammatory agents added cautiously.

• Treating the glaucoma. In many patients with inflammation who are at risk for glaucoma, our recommendation is to treat the inflammation aggressively, and then to follow this effect on the IOP level. In other instances, however, one might detect glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve, or very high pressures (i.e., above 30 mmHg). In these cases, it's appropriate to start the patients on a topical aqueous-suppressant medication (e.g., timolol maleate b.i.d.) in addition to their steroid therapy. Prostaglandin agents are often reserved for later use in uveitic glaucoma since these drugs may increase the risk of additional inflammation.

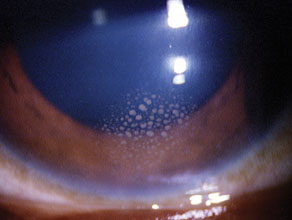

|

| Mutton fat keratic precipitates: a sign of an inflammatory condition like sarcoid. |

When a patient has a high IOP with no visual field defects or signs of optic nerve damage on fundus exam or retinal nerve fiber layer analysis, we recommend basing treatment decisions on the guidelines reported in the Ocular Hypertensive Treatment Study, including appropriate attention to central corneal thickness and its effect on the obtained IOP reading. However, we recommend considering glaucoma treatment in a patient with IOP levels consistently elevated above 28 to 30 mm Hg.

In the patient with severe glaucomatous damage (i.e., vertical cup-to-disc ratio > 0.8), we also recommend aggressive initial therapy with one or more aqueous suppressant agents to achieve a target IOP in the teens. Furthermore, we stress close follow-up, as IOP may fluctuate dramatically in patients with inflammatory glaucoma.

Since patients with uveitis are likely to have recurrent attacks, (sometimes with very high pressures), we recommend close follow-up of the optic disc status over time, comparing baseline disc photographs with those from follow-up visits. Studies have demonstrated that patients may lose up to 30 to 40 percent of the total number of retinal ganglion cells before visual field changes are noted.1

In patients with closed-angle glaucoma and inflammation, posterior synechiae can develop and obstruct the aqueous flow from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber. Examination may also reveal peripheral anterior synechiae as the cause of the pressure rise. When a patient presents with 360-degree posterior synechiae and iris bombé (i.e., secluded pupil), a laser iridotomy will help relieve the obstruction and control the pressure. We recommend two iridotomy holes to prevent the recurrence of pupillary block should one of the iridotomy sites become occluded with inflammatory debris or close due to synechiae.

The Next Visit

A significant portion of the clinical management of uveitis-associated open-angle glaucoma occurs during the follow-up period. After the initial visit, the patient has begun the anti-inflammatory regimen and now must be followed to determine the success of the therapy in controlling both the inflammation and elevated IOP. At this stage, management may be challenging, because the steroids used to control the inflammation may also elevate the IOP. Listed below are several possible clinical scenarios:

1. A patient presents with a severe inflammatory reaction, open angle, and a very high IOP. Following initiation of aggressive steroid therapy, the number of inflammatory cells decreases to trace levels, and the pressure returns to normal. In this case, the clinician rightly concludes that the IOP elevation was likely due to a "trabeculitis" that impeded aqueous outflow.

2. Another patient presents with a similar clinical picture initially, but the IOP remains elevated even after aggressive steroid therapy has caused resolution of the inflammation. This patient may have developed permanent changes in the trabecular meshwork outflow system, and controlling the inflammation will not decrease the IOP level appreciably. In this scenario, the physician should initiate anti-glaucoma treatment using one or more aqueous suppressants. If the clinician suspects that the pressure elevation will only be of short-term duration, he can use oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as well. If the IOP is still not adequately controlled, he may then carefully use a prostaglandin analog in an attempt to avoid the need for glaucoma surgery but watching all the while for increased inflammation from the prostaglandin.

3. Another patient may have a similar presentation but the IOP may increase further after the inflammation is controlled. In this case, the patient likely has pre-existing damage to the outflow channels and the actual IOP level has been masked by the ocular inflammation that reduced aqueous inflow. Controlling the inflammation will paradoxically increase the IOP since aqueous humor production will return to normal levels following successful anti-inflammatory therapy. This patient should be treated with anti-glaucoma agents as in scenario #2.

If the ocular inflammation is uncontrolled after several days or weeks of topical steroid therapy (this time period can vary based on the severity of the inflammation), the clinician should strongly consider starting systemic steroids or immunosuppressive agents, preferably with the assistance of a consulting internist or rheumatologist.

• Steroid responders. It's also possible that the patient in scenario #3 is, in fact, a steroid responder. Even so, the most prudent initial course of action is to treat the inflammation aggressively, since a steroid-associated elevation of IOP usually takes at least two weeks following initiation of steroid therapy to manifest itself. If a patient has residual, low-grade inflammation and elevated IOP, and the physician is uncertain as to whether there is a steroid-response factor, he or she should consider switching to a weaker steroid therapy (e.g., FML). If the IOP decreases, this is confirmation that a steroid response is present.

• Subtenon's injection of steroids. When the ocular inflammation persists and/or the patient has difficulty tolerating the prescribed medical regimen, including oral immunosuppressive agents, the clinician may consider a subtenon's steroid injection. The physician should approach this option with caution since the patient may be a steroid responder. If the patient is a responder, and you give the injection, the IOP may remain elevated for a lengthy period of time as the steroid bolus is finally cleared. Thus, we don't recommend subtenon's steroid injections in patients with signs of steroid responsiveness during follow-up.

Surgical Management

Even after controlling the inflammation, surgery may be the only option for a patient with persistent glaucoma on maximal medical therapy. However, just as the presence of active uveitis makes medical management challenging, it makes surgical management even more so.

In recent years, the focus of surgical management for uveitic glaucoma has shifted away from glaucoma filtration surgery (e.g., trabeculectomy with antimetabolite therapy) and toward placement of glaucoma tube-shunt implants. We believe that this shift is warranted, because it's been our clinical impression that a significant number of trabeculectomies will fail in the long-run in these patients. Persistent inflammation can also worsen and/or prolong postoperative hypotony in patients undergoing filtration surgery.

If the surgeon is considering proceeding with a tube-shunt procedure, he should consider starting the patient on topical and/or oral steroids in the preop period, bolstered with IV steroids on the day of surgery. He may also use oral steroids in the postop period, depending on the risk of continued inflammation. It's also been our clinical impression that a decreased level of inflammation postop increases the chance for surgical success.

One surgical caveat is that the use of an open-tube design (e.g., Baerveldt or Molteno implant) in patients with a history of recurrent uveitis may lead to periods of transient hypotony when the iritis flares up. The recurrent inflammation episode temporarily leads to reduction of aqueous production, and the open-tube design doesn't provide significant restriction to outflow in response.

On the other hand, glaucoma tube shunts with a restricted-flow design (e.g., the Ahmed implant) are also of concern, since the valve mechanism may be blocked by inflammatory debris or fibrin. If this occurs, the surgeon can inject tissue plasminogen activator into the anterior chamber to clear the clogged tube.

Finally, in surgeries with either the open- or closed-tube designs, there appears to be an increased incidence of a postoperative hypertensive phase.

Given all the diagnostic and treatment complexity, managing the patient with uveitic glaucoma requires an individualized case approach. Over time, the clinician will gain a better understanding of the course and severity of any recurrent episodes of inflammation, allowing for more effective therapeutic interventions.

Dr. Tsai is an associate professor of ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma division at Columbia University's Harkness Eye Institute. Dr. Al-Aswad is an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology in the glaucoma division at the Harkness Eye Institute.

1. Quigley HA, Dunkelverger GR, Green WR. Retinal ganglion cell atrophy correlated with automated perimetry in human eyes with glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;107:453-46.