Hypertensive retinopathy has long been regarded as a risk indicator of mortality in persons with severe hypertension, but its value in contemporary clinical practice is uncertain. Previous studies suggest that mild hypertensive retinopathy signs are difficult to detect and measure, while severe hypertensive retinopathy signs are uncommon. In the last decade, however, new population-based studies show that hypertensive retinopathy signs are common in the adult general population 40 years of age and older, including persons without a clinical diagnosis of hypertension.

Patients with moderate hypertensive retinopathy signs may benefit from further assessment of cardiovascular risk (e.g., assessment of cholesterol levels) and, if clinically indicated, appropriate risk reduction therapy (e.g., cholesterol-lowering agents.

Some hypertensive retinopathy signs are associated not only with concurrent blood pressure levels, but are associated with past blood pressure levels, suggesting that they reflect chronic hypertensive damage. Mild hypertensive retinopathy, such as generalized and focal retinal arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking, is only weakly associated with cardiovascular diseases. In contrast, moderate hypertensive retinopathy, such as retinal hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and microaneurysms, is strongly associated with both subclinical and clinical cardiovascular diseases, including stroke and congestive heart failure. Thus, a clinical assessment of hypertensive retinopathy signs in older persons may provide useful information for cardiovascular risk stratification. This article will review what research has revealed about the role of hypertensive retinopathy as a marker for systemic disease and how clinicians can benefit from understanding this association.

Definition

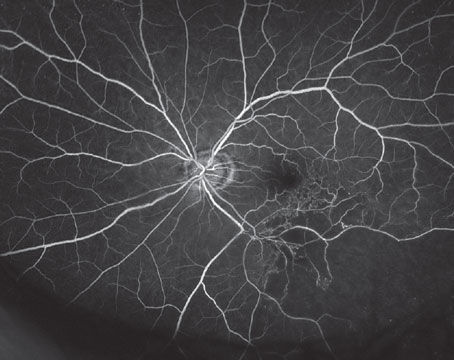

Hypertensive retinopathy refers to a series of clinical signs seen in the retina in persons with elevated blood pressure.1 Hypertensive retinopathy signs can be broadly classified into diffuse retinal signs, such as generalized arteriolar narrowing and arteriolar wall opacification, and localized signs, such as focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous (AV) nicking, and blot and flame-shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and microaneurysms.2

International hypertension management guidelines, including the U.S. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC), support an assessment of hypertensive retinopathy signs for risk stratification.3 These guidelines suggest that hypertensive retinopathy, along with left ventricular hypertrophy and renal impairment, can be considered indicators of target organ damage.

Table Legend: +++ = Strong association (relative risks/odds ratios >2.0), ++ = Moderate association (1.5 to 2.0), + = Weak association

Classification and Epidemiology

The traditional classification of hypertensive retinopathy4 typically consists of four grades of hypertensive retinopathy with increasing severity. Grade 1 consists of "mild" generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing; grade 2 consists of "more severe" generalized narrowing, focal areas of arteriolar narrowing, and AV nicking; grade 3 consists of grade 1 and 2 signs plus the presence of retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, hard exudates and cotton wool spots; and grade 4, sometimes referred to as accelerated (malignant) hypertensive retinopathy, consists of signs from the three previous grades with the addition of optic disc swelling and macular edema. One of the major limitations of this classification system is the difficulty in distinguishing early hypertensive retinopathy grades (e.g., grade 1 from grade 2); thus, a modified classification has been recently proposed (See Table 2).

Recent population-based studies have provided data on the prevalence of various hypertensive retinopathy signs in the general population. Data from these studies indicate that hypertensive retinopathy signs, defined from retinal photographs, are seen in 3 to 14 percent of adult individuals 40 years and older.5–10

There are fewer studies on the long-term incidence of new hypertensive retinopathy signs. Data from the Beaver Dam Eye Study, a study of 4,926 adults aged 43 to 86 years in

Cardiovascular Risk and Disease

• Blood Pressure. There is strong evidence that hypertensive retinopathy signs have a graded and consistent association with blood pressure (See Table 1).5–10 In the Beaver Dam Eye Study, hypertensive individuals were 50 to 70 percent more likely to have retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms, 30 to 40 percent more likely to have focal arteriolar narrowing, and 70 to 80 percent more likely to have AV nicking than normotensive people. In addition, the Beaver Dam Study showed that persons with uncontrolled hypertension (defined as those whose blood pressure was still elevated despite the use of antihypertensive medications) were more likely to develop retinopathy signs than individuals whose blood pressure was controlled with medications.

Several recent population-based studies have used retinal photography to define hypertensive retinopathy signs, including computer-based imaging methods to measure retinal arteriolar diameters. One study that has utilized this technology is the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, a population-based cohort investigation of cardiovascular disease in persons aged 45 to 64 years selected from four

Data from ARIC and other studies provide evidence that the pattern of associations of blood pressure with specific hypertensive retinopathy signs varies. Generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing and AV nicking appear to be markers of cumulative, long-term hypertension damage, and are independently linked with past blood pressure levels measured five to eight years prior to the retinal assessment.11 In contrast, focal arteriolar narrowing, retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, and cotton wool spots reflect more transient changes of acute blood pressure elevation, and are linked only with concurrent blood pressure measured at the time of the retinal assessment.11

Additionally, population-based studies suggest that generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing, a marker of blood pressure damage, may in fact predict the development of incident hypertension.12,13 The ARIC study showed that normotensive participants who had generalized arteriolar narrowing were 60 percent more likely to be diagnosed with hypertension within a subsequent three-year period than normotensive individuals without arteriolar narrowing, independent of pre-existing blood pressure levels, body mass index, and other known hypertension risk factors.12

• Atherosclerosis Risk Factors. In contrast to its strong association with blood pressure, hypertensive retinopathy signs have not been consistently linked to either direct measures of atherosclerosis or its risk factors (See Table 1). The ARIC study, for example, found that generalized arteriolar narrowing was associated with carotid artery plaque but not stenosis, AV nicking was associated with carotid artery stenosis but not plaque, and focal arteriolar narrowing was not related to either carotid artery measure.7

The association of hypertensive retinopathy signs with inflammation and endothelial dysfunction has recently been investigated. Cross-sectional associations of retinal arteriolar narrowing and AV nicking with biomarkers of inflammation (e.g., white blood cell counts) and endothelial dysfunction (e.g., von Willebrand factor) have been reported in the ARIC study7 and other groups.14 These studies emphasize the fact that typical signs of hypertensive retinopathy may be related to vascular processes other than blood pressure.

• Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease. Strong associations between various hypertensive retinopathy signs with both subclinical and clinical cerebrovascular disease and stroke mortality have been reported. The ARIC study showed that individuals with retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, and cotton wool spots were two to four times more likely to develop an incident clinical stroke within three years, even controlling for the effects of blood pressure, cigarette smoking, lipids and other risk factors.15 Among the participants without stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertensive retinopathy signs were also related to changes in cognitive function,16 and cerebral white matter hyper-intensity lesions and atrophy.17,18

A key observation arising from the ARIC study was that the presence of hypertensive retinopathy may offer additional predictive value of clinical stroke risk in individuals with MRI-defined subclinical cerebral disease. Individuals with both MRI-defined white matter lesions and hypertensive retinopathy were 18 times more likely to develop an incident clinical stroke event than those without either white matter lesions or hypertensive retinopathy.17

• Coronary Heart Disease and Heart Failure. Hypertensive retinopathy signs have also been linked with both subclinical and clinical coronary heart disease and congestive heart failure. For example, there have been studies showing associations of various hypertensive retinopathy signs with coronary artery stenosis on angiography,19 and with incident coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction.20 The ARIC study reported that after controlling for pre-existing risk factors, individuals with retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, and cotton wool spots were twice as likely to develop congestive heart failure than individuals without retinopathy.21 In fact, even among individuals considered at low risk of heart failure (those without pre-existing coronary heart disease, diabetes or hypertension), the presence of hypertensive retinopathy signs predicted a three-fold increased risk of heart failure events.

Other Systemic Diseases and Cardiovascular Mortality

A number of systemic diseases have been associated with different hypertensive retinopathy signs (See Table 1). In the ARIC study, individuals with AV nicking, retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms and cotton wool spots were more likely to develop renal dysfunction compared to those without these signs, independent of blood pressure, diabetes, other risk factors and hypertension status.22 Generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing also predicts the incidence of type 2 diabetes, independent of traditional diabetes risk factors.16, 23

It has long been known that in persons with untreated hypertension, hypertensive retinopathy signs are indicators of mortality.4 In a more recent analysis of the Beaver Dam Eye Study, individuals with retinal microaneurysms and retinal hemorrhages were twice as likely to die from cardiovascular events as those without these signs.24

Clinical Applications

How should physicians use these data? Is a retinal examination still relevant in today's clinical practice? Recent studies suggest that the information that can be determined from an assessment of the retinopathy status is independent of traditional risk factors, and the presence of retinopathy signs appears to indicate susceptibility and the onset of preclinical systemic vascular disease. For clinical utility, a simplified, three-grade classification system for hypertensive retinopathy is shown in Table 2 (below) and a suggested approach for patients with various hypertensive retinopathy grades is shown. Patients with mild hypertensive retinopathy signs will likely require routine care and blood pressure control should be based on established guidelines. Patients with moderate hypertensive retinopathy signs may benefit from further assessment of cardiovascular risk (e.g., cholesterol levels) and, if clinically indicated, appropriate risk-reduction therapy (e.g., cholesterol-lowering agents). Patients with severe hypertensive retinopathy will continue to need urgent, immediate, anti-hypertensive management.

It is uncertain at this time if hypertensive retinopathy signs regress. There have been clinical reports of regression of retinopathy with control of blood pressure.25 However, further studies are needed to determine the value of monitoring retinopathy status over time as an indication of changing cardiovascular risk.

Research indicates that hypertensive retinopathy is a risk marker of various systemic vascular diseases. In particular, recent studies show that moderate hypertensive retinopathy signs (which occur in up to 10 percent of adult persons 40 years and older) are strongly associated with risk of subclinical and clinical stroke, other cerebrovascular outcomes, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality independent of traditional risk factors. A clinical assessment of hypertensive retinopathy signs may therefore provide important clinical information for cardiovascular risk stratification.

Dr. Wong is a professor of ophthalmology at the Centre for Eye Research

1. Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. NEJM 2004;351:2310–7.

2. Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Survey Ophthal 2001;46:59–80

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, H.R. B, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289:2560–72.

4. Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: their course and prognosis. Am K Med Sci 1939;197:332–43

5. Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE, et al. The relation of systemic hypertension to changes in the retinal vasculature: The Beaver Dam eye study. Trans Am Ophthalmol 1997;95:329–50.

6. Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE, et al. Hypertension and retinopathy, arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking in a population. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:92–8.

7. Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BEK, et al. Are retinal arteriolar abnormalities related to atherosclerosis? The Atherosclerosis in Communities Study. Arteroscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:1644–50.

8. Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Leung H, et al. Hypertensive retinal vessel wall signs in the general older population: the

9. Wong TY, Klein R,

10. Yu T, Mitchell P, Berry G, et al. Retinopathy in older persons without diabetes and its relationship to hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:83–9.

11. Wong TY, Hubbard LD, Klein R, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and blood pressure in older people: the Cardiovascular Health Study. British J Ophthal 2002;86:1007–13.

12. Wong TY, Klein R,

13. Wong TY, Shankar A, Klein R, et al. Prospective cohort study of retinal vessel diameters and risk of hypertension. BMJ 2004;329:79.

14. Ikram MK, de Fong FJ, Vingerling JR, et al. Are retinal arteriolar or venular diameters associated with markers for cardiovascular disorders? The

15. Wong TY, Klein R, Couper DJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and incident stroke: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Lancet 2001;358:1134–40.

16. Wong TY, Klein R,

17. Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, retinopathy, and incident clinical stroke. JAMA 2002;288:67–74.

18. Wong TY, Mosley TH, Jr., Klein R, et al. Atherosclerosis risk in communities: Retinal microvascular changes and MRI signs of cerebral atrophy in healthy, middle-aged people. Neurology 2003;61: 806–11.

19. Michelson EL, Morganroth J, Nichols CW, et al. Retinal arteriolar changes as an indicator of coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med 1979;139: 1139–41.

20. Wong TY, Klein R,

21. Wong TY, Rosamond W, Chang PP, et al. Retinopathy and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA 2005;293:63–9.

22. Wong TY, Coresh J, Klein R, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and renal dysfunction: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Amer Soc Nephrol 2004;15:2469–76.

23. Wong TY, Shankar A, Klein R, et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing, hypertension, and subsequent risk of diabetes mellitus. Arch Int Med 2005;165: 1060–5.

24. Wong TY, Klein R, Nieto FJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and 10-year cardiovascular mortality: A population-based case-control study. Ophthalmology 2003;110:933–40.

25. Bock KD. Regression of retinal vascular changes in antihypertensive therapy. Hypertension 1984; 6:158–62