When patients present with chronic blepharoconjunctivitis, the condition can cause an unexpected sequela: a headache for the ophthalmologist. The physician has to analyze the various signs, symptoms and differential diagnoses to get to the root of the problem, then select the right course of action to try to make sure the eye stays quiet—at least for a while. Here, expert clinicians share their tips for diagnosing the cause of the inflamed eye and treating it successfully.

Determine the Cause

The history and physical exam can help you categorize the blepharoconjunctivitis, which makes it easier to treat, clinicians say.

"Make sure to note if there's a history of systemic or skin conditions that might predispose the patient toward blepharoconjunctivitis," says David Harris, MD, a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology's cornea and external disease panel. "For instance, a history of rosacea would lead you to consider meibomian gland dysfunction, while a history of discoid lupus might point to that as the cause of the blepharoconjunctivitis. If the patient has had bouts of atopy with eczema, consider atopic blepharoconjunctivitis. If he or she has been in contact with children recently and also has lumps on the eye and associated ocular redness, make sure you rule out molloscum contagiosum. Also, ask about herpes, which might be behind a history of recurrent ulcerations of the lid, cornea or conjunctiva."

When performing the exam, here's a review of the types and causes of blepharoconjunctivitis, based on the signs and symptoms.

• Anterior disease. This variety is usually marked by infection. "The first step in any case of blepharoconjunctivitis is evaluating the lid margins," says Garden City, N.Y., corneal specialist Eric Donnenfeld. "In anterior disease, it's usually a staphylococcal bacterial infection involving the lid margins and lashes. It's marked by scurf formation, erythema, small pustules, lash loss and crusting of the lid margin. These patients will often complain of irritation in the eye that is insidious, coming on slowly and then lasting all day. These patients commonly have sequelae to the anterior blepharitis such as hordeolum and staphylococcal immune disease such as subepithelial infiltrates."

Culturing is the next step when you suspect a bacterial cause. "If I think it's bacterial, such as staphylococcal, it helps to have a culture in that situation in order to treat it with topical antibiotics based on the culture result," says Dr. Harris.

|

• Angular blepharoconjunctivitis. This is caused by the Moraxella organism or staph. "In this, the lateral canthal angle will be involved, with the redness, scaling and irritation all pointing to that area as a source of discomfort or pain," says Dr. Harris. "You may actually find Moraxella in the makeup the patient may be reusing. That's the classic story, that Moraxella is found in the patient's makeup, though that's not very common in my practice. I've cultured the organism only a few times when looking for it."

• Posterior disease. This form involves a problem with the meibomian glands. "With posterior blepharitis, you examine the meibomian gland orifices, looking for inspissated glands with thickened secretions, often with oil droplets on the lid margin," explains Dr. Donnenfeld. "Also look for loss of meibomian gland orifices. These patients often have irritation, foreign body sensation and burning that's worse in the morning than at night, which is the opposite of aqueous-deficient dry eye. They may also have a history of chalazia and dry-eye symptomatology."

Dr. Harris details what to look for in the gland secretions. "At the slit lamp, observe the openings of the meibomian glands and express some material out," he says. "It should be clear. If they're obstructed, you may get nothing out, or you may get a milky looking material or a waxy plug.

"For people with chronic blepharoconjunctivitis, you can do meibomography, or retro-illumination of the tarsal plate," Dr. Harris adds. "You may see a dropout of meibomian glands that has occurred due to chronic posterior blepharitis."

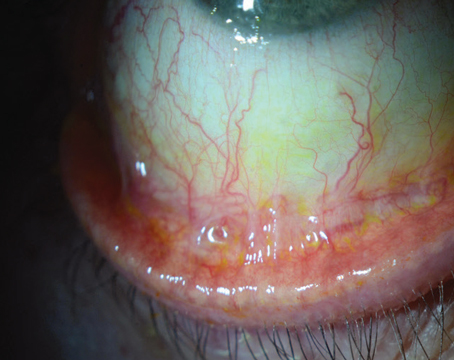

Another important clinical sign physicians say to watch for is saponification, or the creation of soap bubbles, in the tear film in patients with a seborrheic form of meibomian gland dysfunction. This may be a sign that bacterial action is converting meibomian oils into fatty acids, and from there, into soap-like compounds. These compounds form foam in the tear film. "This is a helpful sign," says Dr. Harris. "It's especially helpful in cases that are so mild you can't see obvious meibomian gland pathology, chalazion or milky discharge from the gland orifices."

|

• Seborrheic blepharoconjunctivitis. This is different from the seborrheic dysfunction of the meibomian gland discussed earlier, and is associated with seborrheic dermatitis. "These patients tend to have greasy scales on the lashes," notes Dr. Harris. "A lot of these patients will have scaling of the brow between the lids and evidence of seborrheic dermatitis on the face and scalp."

• Atopic blepharoconjunctivitis. The ocular inflammation can also be associated with allergy, and Dr. Donnenfeld says such eyes and lids will be red and there may be a whitish thickening of the lid margin. "The patients may have cracks on their skin, including on their lid margins, and many times they have black circles around their eyes," says Dr. Donnenfeld. "If you look at their flexor surfaces, such as their forearms, you can often see dark, thickened areas of skin there, as well. They'll mostly complain of ocular itching and allergy symptoms that will get worse with the allergy season." Dr. Harris notes that atopic disease can involve the lid, conjunctiva and the cornea.

• Rosacea. Dr. Jackson says that ocular rosacea is commonly associated with blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye. "The primary features are flushing, nontransient erythema, papules, pustules and telangiectasia," he says. "There will usually be one or more of these features across the central area of the face. Though many patients with ocular rosacea lack the typical skin signs at first, you can usually see telangiectasia and erythema." There will be meibomian gland dysfunction in 90 percent of cases and anterior blepharitis in half of them.1

• Molloscum contagiosum. Dr. Harris says that, for this viral form, the physical signs are bumps on the lid, redness, and possibly skin lesions elsewhere on the body that are itchy and irritated. As mentioned earlier, the patient may acknowledge spending some time recently with children, in whom the virus is common. The patient may also have follicular conjunctivitis and an enlarged preauricular node.

• Herpes. This tends to be recurrent and patients are aware of it, but Dr. Harris says it's possible to have a primary herpes involvement of the lid and conjunctiva in patients with no history of herpes simplex involving that part of their body. "For instance, you may see a wrestler who gets inoculated with herpes simplex in the lid and face and then gets blepharoconjunctivitis from it," he says. "I might do a viral culture to confirm my suspicion of herpes simplex if the history isn't good." He adds that the blepharoconjunctivitis may also be secondary to herpes zoster, or shingles, the presence of which would be readily apparent on exam.

• Pubic lice (Pediculosis pubis). Considered a venereal disease when found on the lids, the lice will cause a red, itchy eye. The diagnosis can be made on exam, as the lice will be clearly visible. Dr. Harris says it's a good idea to refer the patient to a dermatologist to check for lice elsewhere.

• Sebaceous cell carcinoma. This is a cancer than masquerades as blepharoconjunctivitis. "This is the malignant blepharoconjunctivitis we worry about the most," says Dr. Harris. "Sebaceous cell arises in the meibomian glands and can present with a red lid and conjunctiva without a visible mass being present. Lash loss, particular focal loss, in such a setting may point toward a malignancy and the need to do a full-thickness lid biopsy."

Quieting the Eye

Once you zero in on the cause of the blepharoconjunctivitis, it's time to tailor the treatment to it. Here's what your colleagues recommend:

• Anterior blepharoconjunctivitis. "For those anterior blepharitises that are purely infectious, we'll use an antibiotic or antibiotic steroid combination to settle them down pretty quickly," says Dr. Jackson. "In Canada we have slightly different products than in the United States, namely fusidic acid gel, which we have patients apply to the lid margin at bedtime.

|

Dr. Harris will base his antibiotic treatment on the culture, though he says he might use tobramycin if he were just going to treat it empirically. "We see more methicillin-resistant staph aureus causing blepharoconjunctivitis," he says. "But this is sensitive to common aminoglycosides such as tobramycin or gentamicin and I'll use those topically, if possible. I'll usually use topical treatment for a couple of weeks and, if they get better, just follow them. If they don't improve, that's when I'll be concerned about a deeper infection and will go with a systemic antibiotic, based on the culture." He also has the patient use a combination of warm compresses and wiping the lid margins with very dilute baby shampoo to debulk the organisms and debris at the base of the eyelashes.

Be on the lookout, too, for chronic carriers of staphylococcus. "If I'm using an antibiotic that should be effective based on culture but the patient continues to get worse when I take him off of it, that's when I get suspicious that he's a chronic carrier of staph," says Dr. Harris. Around 20 percent of the general population are colonized with S. aureus, carrying it in their anterior nares and/or around their ears.2 Without consultation with and extensive treatment by an infectious disease specialist, they'll never rid themselves of the bacteria.

• Posterior disease. For posterior blepharoconjunctivitis, Dr. Donnenfeld says the most important treatments are hot compresses, the heat from which will melt the blocked oil glands. He will often have patients put a potato in the microwave to get it warm, but not scalding, and then wrap it in a damp washcloth. They can then place the warm bundle on the eye for 10 to 15 minutes. "Nutritional supplements are very helpful and under-recognized in these patients," adds Dr. Donnenfeld, who suggests patients use TheraTears Nutrition. His patients take three tablets in the morning.

|

Dr. Donnenfeld reserves topical azithromycin for a third line of therapy. "It has many of the common anti-inflammatory effects of doxycycline, but it penetrates very well into tissue. So, when you give a topical drop, because of the vehicle in AzaSite, it adheres to the lid margin, gets absorbed there and you get excellent tissue effects on the lids. We'll have the patient use hot compresses at night before bed, then put in a drop of AzaSite, close the eye and rub the lid margins—called drop and massage—and do that once a day for a month." If patients still have recurrent posterior blepharitis despite the other treatments, Dr. Donnenfeld will try Restasis, b.i.d.

• Seborrheic disease. For seborrheic blepharitis with some mild conjunctival injection, Dr. Donnenfeld says the abnormal secretions are very hydrophobic, and therefore hot compresses don't work well. For these cases, he'll have the patient take a selenium-based dandruff shampoo and, after using a hot compress in the shower, combine half a capful of shampoo with half a capful of water and put the mixture on a washcloth. The patient then massages the lid margin with the cloth to break down the particles. "If you use this too much, it's toxic, so I have them use it just once a week," he notes.

• Atopy. For patients suffering from atopic blepharoconjunctivitis, Dr. Harris will "give them a short burst of oral steroids to calm it down if they're suffering significantly." However, he says the off-label use of a new agent, tacrolimus (Protopic), has been a great help. "I've been able to avoid oral steroids in this group by using tacrolimus, a strong cell-mediated immunosuppressant gel that's used for atopic dermatitis," he says. "It can be used off-label for atopic blepharoconjunctivitis, and these patients can respond dramatically to it.

"An important thing to note in these patients is they have an increased incidence of herpes simplex keratitis and keratoconus," adds Dr. Harris. "As such, and particularly if there's any question about them having had herpetic eye disease, I may put them on prophylactic systemic antiviral treatment, such as acyclovir b.i.d., during the period of time I'm giving them steroids to help avoid a flare-up in the middle of treatment." Dr. Harris says that although tacrolimus has worked well, these patients still may require both oral and topical steroids to control their atopic blepharoconjunctivitis. He'll also send the patient to an allergist for the systemic component of the disease if he's never been to one previously. As an added pearl, Dr. Donnenfeld warns against using hot compresses in atopic patients because they can macerate the lid margin.

• Herpes. For herpetic causes of blepharoconjunctivitis with no corneal involvement, Dr. Harris prescribes a systemic antiviral such as acyclovir (Zovirax) 200 mg five times a day, famciclovir (Famvir) 500 mg t.i.d. or valacyclovir (Valtrex) 500 mg t.i.d. for a week to eradicate it. "If it's caused by herpes zoster, I'll use the same agents at higher dosages, such as acyclovir 800 mg five times a day or valacyclovir 1 g t.i.d. I won't usually use topical antivirals such as Viroptic [trifluridine] unless there's corneal involvement, a dendrite or ulceration of the conjunctiva."

• Molloscum and lice. For blepharoconjunctivitis caused by molloscum contagiosum, Dr. Harris says you can curette the lesions and scrape them out or freeze them to activate the body's immune system, which will cause the rest to involute. "I usually prefer the latter approach," he says. And for an infestation of pubic lice, he says that any antibacterial ointment will kill them.

Dr. Jackson says having the patient take a proactive role in maintaining his or her lid and ocular health is important in managing recurrent blepharoconjunctivitis. Says he, "Sitting down with the patient and reviewing the treatment and the philosophy behind the treatment is one of the key parts of managing the patient's condition." REVIEW

1. Alvarenga LS, Mannis MJ. Oculr rosacea. Ocul Surf 2005;3:41-58.

2. Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997;10:505-20.