Systemic Disease and Dry Eye

There is a well-known association of several systemic diseases associated with dry-eye syndrome, among them Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma and systemic lupus erythematosus.1 Sjögren’s syndrome is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by white blood cells attacking the patient’s moisture-producing glands, including the lacrimal and salivary glands. Sjögren’s syndrome is classified as either primary or secondary. Although both are systemic diseases, primary Sjögren’s syndrome causes early and gradual decreased function of the lacrimal and salivary glands and can include many extraglandular conditions. Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in people who have another autoimmune connective tissue disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Sjögren’s syndrome affects an estimated 4 million people in the United States, of which 3 million are undiagnosed, yet it is one of the three most common autoimmune diseases. Most importantly, aqueous-deficient dry eye is associated with decreased lacrimal secretion and is a common early symptom of Sjögren’s syndrome and a hallmark of the condition.1-3 Sjögren’s syndrome can progress to the entire body in the form of systemic manifestations, such as kidney dysfunction, lung disease and increased risk of lymphoma. Lymphoma is a serious complication of Sjögren’s disease that increases in risk as the disease progresses.

|

Recent Clinical Findings

Sjögren’s is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental and hormonal factors. The initiating factor may come from one or more events and is also likely to have a basis in genetic predisposition. Early and accurate diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome is an important factor in limiting complications of the disease, yet there is currently an average delay of 4.7 years for patients to receive an accurate diagnosis.1 Achieving an accurate diagnosis has historically proved challenging, requiring a number of diagnostic tests including serology. Traditional serological biomarkers associated with Sjögren’s syndrome—Sjögren-specific antibody A (SS-A), Sjögren-specific antibody B (SS-B), rheumatoid factor (RF), and antinuclear antibody (ANA)—have some limitations, including a low clinical sensitivity (SS-A, SS-B), low specificity (ANA, RF), lack of detectability and manifestation late in disease progression; the result of systemic-based, rather than organ-specific, markers.7

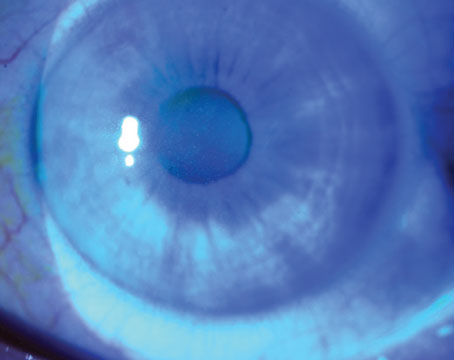

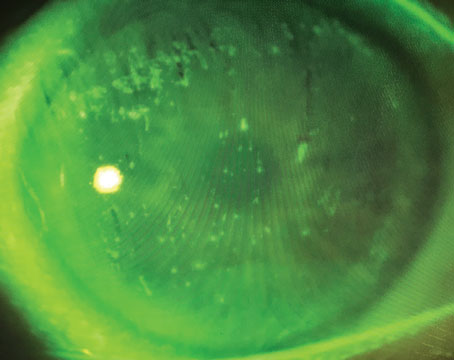

A recently developed, advanced diagnostic panel for early identification of Sjögren’s syndrome in dry-eye patients (Sjö, Nicox Inc.), tests patients for three new biomarkers—salivary gland protein-1 (SP-1), carbonic anhydrase-6 (CA-6) and parotid secretory protein (PSP)—that detect Sjögren’s syndrome earlier and with a high specificity and sensitivity, in addition to traditional biomarkers (See Figures 1 & 2). These new autoantibodies are gland-specific and detect Sjögren’s syndrome with a high specificity and sensitivity.4 SP-1 antibodies have the greatest specificity and sensitivity for early Sjögren’s syndrome, and autoantibodies to CA-6 add additional sensitivity to the diagnosis of early Sjögren’s syndrome along with PSP, SS-A and SS-B.

|

Thirty-three patients were found to have markers of Sjögren’s syndrome, representing 36.7 percent of those patients tested. Thirteen of these patients were defined as early Sjögren’s syndrome; 13 were defined as Sjögren’s syndrome; and seven were defined as secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Of the 33 who tested positive for markers of Sjögren’s syndrome, 28 were female (35.9 percent of females tested were positive for markers of Sjögren’s syndrome) and five were male (41.7 percent of males tested were positive for markers of Sjögren’s syndrome). Seven were positive for markers indicative of rheumatoid arthritis (See Table 1). Surprisingly, a large percentage of patients who presented with only dry eye were found to have Sjögren’s syndrome and were detected early.

Diagnosis Changes Management

|

In regards to ocular signs and symptoms, the specific treatment regimen for the Sjögren’s-syndrome patient will depend on the severity and stage of the disease. Early treatment to try to normalize the tear film and break the cycle of inflammation may protect the ocular surface from subsequent complications (scleritis, keratitis and uveitis) and improve patients’ quality of life. In my practice, initial treatment consists of using artificial tears every two hours followed by cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% (Restasis) and loteprednol etabonate, with follow-up visits scheduled every six months. However, if the patient tests positive for Sjögren’s, then follow-up is every three months.

Some patients present with dry-eye complaints at their initial visits and are tested for Sjögren’s syndrome. Others don’t take the test until after multiple visits and repeated complaints of symptoms that don’t improve. Once patients are aware of their diagnosis, their expectations change and their complaints diminish. They understand they are taking medications, not to improve, but to prevent progression of the disease.

The overlap between Sjögren’s syndrome and dry eye means that eye-care professionals are in a unique and critical position to identify Sjögren’s years ahead of the current standard. Not only can we make a difference in the lives of our patients by the early identification of a serious autoimmune disease, but knowing if there is an underlying cause of dry eye can also help us to better manage their ocular symptoms more effectively. Our findings support the need for increased diligence for eye-care professionals managing dry-eye patients and the recommendation that the potential presence of Sjögren’s syndrome should be considered in all dry-eye patients, regardless of disease stage. REVIEW

Dr. Dauhajre is an ophthalmologist at Mount Sinai Hospital of Queens in New York. Mr. Teofilo Atallah is a pre-med student at New York University School of Medicine. The authors report no financial interest in any product discussed, and they received no financial support for their in-house study.

1. Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation. Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation. 2001. Available at http://www.sjogrens.org. Accessed September 5, 2013.

2. Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1275-1284.

3. Liew M, Zhang M, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of Sjögren’s syndrome in a prospective cohort of patients with aqueous-deficient dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:1498-1503.

4. Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, Mandl T, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson L T H. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;803:65:796-803.

5. Voulgarelis M, Dafni U G, Isenberg D A, Moutsopoulos H M. Malignant lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1765-1772.

6. Utine CA, Akpek EK. What Ophthalmologists Should Know About Sjögren’s Syndrome. European Ophthalmic Review 2010;4(1):77-81.

7. Shen L, Suresh L, Lindemann M, et al. Novel autoantibodies in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol 2012;145:251-255.