Whenever a new technology simplifies a task, some people become concerned about the impact it will have on existing skills. (Even in ancient times, the development of writing apparently alarmed many on the grounds that it would undermine people’s ability to remember vast amounts of information.) Such fears are not entirely unfounded, of course.

Today, those kinds of fears are being expressed in connection with femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Will young surgeons fail to learn the manual skills so familiar to established surgeons? Will the new tool upset the status quo by making more individuals capable of doing what only an expert could do before? Here, surgeons and educators share their thoughts on these questions.

Resident Competency at Risk?

“For years I’ve heard talk about how automated techniques will compromise residents’ competency,” says Robert Osher, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati and in private practice at the Cincinnati Eye Institute. “Many ophthalmologists used to say, ‘If residents only do phaco, will they forget how to express a nucleus or take out cortex manually?’ It’s the same concern today with laser phaco.”

Dr. Osher believes this concern is largely unwarranted. “Training programs are obligated to make sure that students are capable of handling manual situations because sooner or later everyone, even a sophisticated, experienced surgeon, has a machine problem or a complication that forces him to fall back on his manual skills,” he says. “So it’s going to be the responsibility of all residency programs to keep up residents’ exposure and practice. And that will be easier than ever to do thanks to the surgical simulators that the current generation of students have available to them.”

James P. McCulley, MD, FACS, FRCOpth, is professor and chairman of the department of ophthalmology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, which has the largest residency training program and one of the largest fellowship programs in the country. Currently, Dr. McCulley says the school does not have a femtosecond laser cataract system because of the cost, but he hopes the technology will eventually be available to the vast majority of training programs.

“People in training will still have to be taught the manual skills,” he agrees. “There will be times that for one reason or another the femtosecond laser will not be available; either the laser will be down, or it won’t be possible to dock an individual patient’s eye, or for some reason the patient won’t be a candidate for the femtosecond laser procedure. I think it’s absolutely critical that people be taught and maintain the skills needed to do the procedure manually.

“Consider the evolution of phaco,” he continues. “We went from intracaps to extracaps, and then from manual extracaps to phaco. Nevertheless, it’s critical to continue to teach residents how to do manual extracaps because there are times when it’s not possible to do phaco—usually because something has gone awry with the phaco procedure and you need to convert. Likewise, it’s absolutely critical that residents be taught how to do everything in the phaco procedure manually, in addition to learning to use the femtosecond laser.”

Dr. McCulley adds that schools don’t necessarily attempt to maintain every previous skill set. “When we did intracaps, we took everything out with the capsule intact,” he notes. “We no longer try to teach our residents that skill set, because intracaps represented a completely different surgical approach compared to extracaps. In contrast, phaco is a mechanized way of doing an extracap; they’re both extracapsular procedures, and there are times that we have to do the procedure manually. Similarly, the laser will replace blades and needles to some degree, but not completely; it’s still an extracapsular procedure, and we’ll still need the manual skills.”

Dr. McCulley believes that the manual phaco skills will continue to be taught to residents for decades to come. “It would be irresponsible to stop teaching those skills,” he says. “Until we reach the point at which cataract surgery is completely revolutionized relative to the way we do it now, the skills needed to perform a manual extracap and the manual steps associated with phaco will not go away.”

Shifts in Training

Although residents will still be taught to perform surgery manually, the existence of laser cataract is likely to cause some changes in how training occurs. “Historically, residents were taught to do manual extracaps first; then they were taught to do phaco because phaco was a newer procedure,” says Dr. McCulley. “However, in recent years, we’ve reversed that. Today, our residents learn to do phaco first, then manual extracap, because the latter is a more difficult procedure. For the same reason, once the femtosecond laser system is available, our beginning phaco surgeons may start off having their surgery enabled with the femtosecond laser and then move on to gaining the skills to do the procedure manually.

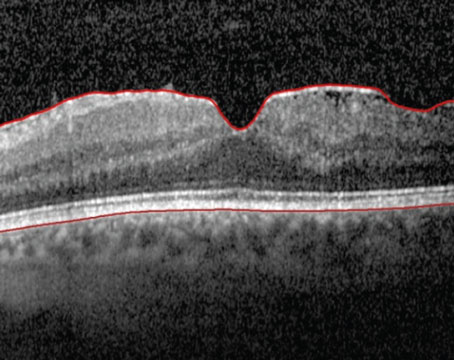

“The fact that the laser system will manage some of the more difficult aspects of the surgery, such as the capsulorhexis and the breakdown of the nucleus, will be an advantage,” he continues. “These steps are associated with some of the most common surgical complications, and they are some of the toughest parts of the procedure for beginning surgeons to learn. The laser can also create a self-sealing cataract wound—another tough thing for the early surgeon to master. Although I can see residents and fellows using the laser for selected patients no matter where they are in their training, I think this technology will be particularly useful during the learning curve of the residents early in their training. It will decrease the number of complications and the risks associated with the procedure.”

Dr. Osher believes that the femtosecond laser won’t be used in the vast majority of cataract cases—at least in the foreseeable future—and that will be reflected in resident training. “This often happens with advanced technologies,” he says. “Consider toric or multifocal lenses; the vast majority of cases don’t use them. Of course, ultimately the superior technology will prevail, as phaco prevailed over extracap, but this is a long timetable we’re looking at.

“It’s always the responsibility of training programs to ensure that residents learn the most current techniques and newest technologies, just as active surgeons need to do,” he notes. “But I think that like toric lenses today, femtosecond laser cataract surgery will only have a limited impact on resident training for now.”

Impact on Current Surgeons

Another concern many surgeons have expressed is that having the laser system perform some of the most difficult parts of the procedure will upset the status quo by allowing less-capable surgeons to perform the surgery.

Dr. Osher doesn’t see this as a problem. “This is the same argument I heard when we transitioned to phaco,” he says. “People said that using smaller incisions would help the surgeons who aren’t as good at cataract surgery. And that is, in fact, what happened. And when the first foldable lens came out, people said it would help the less-skilled surgeon, as if there was a reward for the superior surgeon being able to do well under both circumstances. There isn’t. We’re all trying to do things better. If a new technology helps the less-skilled surgeon make a perfect rhexis, that’s great. There’s no trophy given for the surgeon who makes the best manual rhexis.

“The bottom line is that we have to provide the very best and safest technology and technique for every patient,” he continues. “If this provides that advantage, then it’s a good thing. I don’t care if it reduces the disparity between a great surgeon and a good surgeon. The bottom line is, the ultimate destination we’re trying to reach on this journey is excellence.”

|

“Suppose you’re a very experienced surgeon—a superstar,” he continues. “Now you’re faced with a patient whose one remaining eye has pseudoexfoliation, a lax zonule, a pretty dense cataract and a low endothelial cell count. And the patient is world famous. Would you like it if that nucleus was already partially divided? I would!

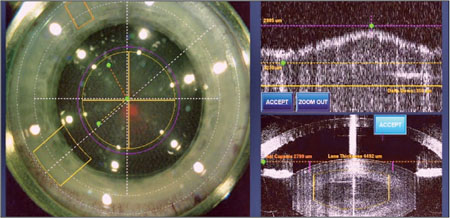

“Of course, you don’t get this advantage with the snap of a finger,” he adds. “You have to buy an expensive machine and you have to be diligent about learning to use it, although the learning curve isn’t ridiculously steep. The hardest part of the learning curve is learning to dock appropriately, but LASIK surgeons learn that with the Intralase pretty quickly. If you can learn to do phaco, you can learn to do femtosecond laser phaco in a relative heartbeat.”

Dr. McCulley agrees the technology has the potential to help all surgeons, not just those who have weaker surgical skills. “The femtosecond laser should improve outcomes even if you’re an accomplished surgeon with established manual surgery skills,” he says. “The wound will be better constructed than one can typically do manually, and the rhexis will be much more standardized, facilitating consistent effective lens position. That will help us hit the postop refractive target more accurately with our IOLs. In addition, everyone has a complication once in a while, and this kind of technology should decrease the incidence of those as well.”

The Cost Factor

Another concern that’s been raised is whether the high cost of entry will limit this technology to large practices run by successful cataract surgeons who are less likely to need the high-tech laser assist—and keep it from the less-skilled surgeons who would benefit the most from its help. Dr. Osher doesn’t think this will happen.

“Again, consider the history of any new technology,” he says. “I heard this when viscoelastics were introduced in the 1970s. It was said that really good surgeons wouldn’t need it and lower-volume surgeons wouldn’t have the financial means to afford it. That turned out to be a total joke. Today, everyone uses viscoelastics.

“If femtosecond laser cataract proves to be a superior technology, everyone will embrace it,” he continues. “With more advanced-technology intraocular lenses appearing and likely to become the standard in the United States over the long term, any technology that allows the surgeon to get a more predictable result and have more confidence in his outcomes will be adopted by nearly everyone. Yes, it will take time to figure out how everyone will gain access to it, given the cost. But there will clearly be opportunities as more competing machines appear and become more affordable.

“Right now we’re just at the very beginning of the trip,” he adds. “There are a lot of details that will need to be worked out. Not just cost, but efficiency, who does it, where it’s done and how to do it best. That’s what happened with multifocal lenses. I started working with multifocals in the 1980s, and they’re totally different now. Likewise, when I started phaco it was a completely different procedure. Now it’s done through a tiny incision with incredibly advanced technology that gives the surgeon amazing control. It’s not even the same operation.

“That’s what’s going to happen with femtosecond laser cataract,” he concludes. “This is just the very beginning of an evolution that I hope makes everyone a better surgeon, makes outcomes more predictable and allows patients to have better results.” REVIEW

Drs. Mackool and McCulley are consultants for Alcon/LenSx. Dr. Osher is a consultant for several of the companies who manufacture femtosecond lasers but has no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.