The surgical treatment of pterygium has long been a challenge for corneal specialists. However, in recent years new approaches using fibrin tissue adhesive and amniotic membrane placement have dramatically improved cosmetic results for patients and significantly reduced postoperative complications. While traditional methods had recurrence rates as high as 50 percent, these newer techniques can lower recurrence rates to less than 1 percent.

Our practice has performed more than 1,000 procedures using the three techniques I'll describe here: pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting; removal of pterygium with placement of an amniotic membrane graft; and a combined procedure using conjunctival autografting with the placement of an amniotic membrane in the conjunctival space. The latter technique is reserved for patients with a higher risk of recurrence, based on size, level of inflammation and a history of prior excision.

Determinants of Success

The choice of procedure depends on the surgeon's comfort level. In my experience, pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting and the combined procedure with placement of an amniotic membrane provide the lowest rates of recurrence. The second procedure, pterygium removal with placement of an amniotic autograft, additionally requires the application of mitomycin, a use some surgeons avoid out of concern for corneal or sclera melt.

Two factors determine successful pterygium excision: complete removal of the pterygium itself; and placement of a graft in place of the pterygium that will serve as a barrier to new growth. High-risk cases require that you address the surrounding subconjunctival space, as the Tenon's fascia is thought to provide the fibroblasts that lead to recurrence. Some surgeons believe that wide excision of this Tenon's fascia is necessary, but I've found that such wide excision can lead to significant bleeding during surgery, exposure of orbital fat and resulting scar tissue that is both unsightly and uncomfortable. So when we use amnionic membrane, we use it not just in the site of pterygium but also in the subconjunctival space from which these fibroblasts arise.

Fibrin Adhesive Used Off-label

I must caution that the use of fibrin adhesive in pterygium surgery is an off-label use. Fibrin adhesives have been used commonly in other types of surgery and have had specific uses in ocular surgery, including for epithelial ingrowth after LASIK, for lamellar keratoplasty and scleral patch, and for clear cornea cataract surgery.

Fibrin adhesive is a two-part material consisting of one part fibrinogen and one part thrombin. This material is available from two manufacturers in the

Balanced salt solution is the ideal diluent because it includes calcium chloride, which thrombin needs to catalyze the polymerization of fibrinogen. Our own laboratory testing has shown that diluting thrombin does not reduce the tensile or shear strength of the adhesive. A 1:1 solution polymerizes in 10 to 15 seconds; a 1:10 solution in 45 to 60 seconds; and a 1:100 diluent in about two minutes.

When using a fibrin adhesive, never use more than you need. The axiom "less is more" truly applies here. I use a thin layer and then squeegee it with the smooth tip forceps. Avoid manipulating the adhesive after it has polymerized.

Any use of a pooled plasma product carries risk. Because of this and the off-label application of fibrin adhesive in pterygium surgery, I advise including this disclosure in your informed consent discussion with the patient.

Excision & Conjunctival Autograft

Pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting is a fairly simple procedure and requires no special supplies. The recurrence rate is less than 1 percent in low-risk individuals. This technique involves removal of the pterygium itself with point 12 or point 3 corneal forceps and Westcott scissors. The head of the pterygium is avulsed from the cornea. Scraping the area with a 15 blade and then a diamond burr can remove residual attachments of Tenon's fascia and conjunctiva.

Next, I direct my attention to the superior conjunctiva, where I make a snip away from the limbus and then use Westcott scissors with blunt dissection to create a very thin graft of only conjunctiva. I then carry this dissection into the limbus to bring along limbal stem cells, as these are thought to provide a barrier to recurrence at the limbus. Once I cut the graft free, I lay it with its epithelial side against the corneal epithelium and move it nasally toward the limbus at the excision site.

I apply thrombin sparingly to the bare sclera site, and then fibrinogen, dispensing each from separate 1-cc syringes without a needle. I apply the fibrinogen to the stromal side of the conjunctival graft, taking care not to mix the two yet. These two materials mix when I invert the graft in the "cut and paste" technique first described by Gabor Koranyi, MD.1

This is when I can squeegee the graft with forceps to create a thin interface for the adhesive and to approximate the wound edges. Finally, I trim any excess graft tissue with scissors.

At the conclusion, the eye is patched and shielded over a fluoroquinolone antibiotic and diluted betadine (off-label use). I instruct the patient to use both prednisolone 1% and a fluoroquinolone four times a day, and a topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drop as directed. The NSAID drop significantly reduces postoperative discomfort.

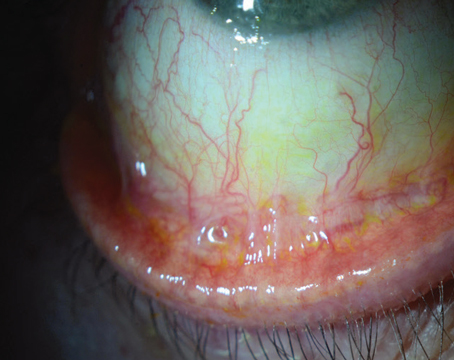

Postoperatively, a moderate amount of chemosis in the graft and subconjunctival hemorrhage is common. This usually clears without incident in one to four weeks. A mild dehiscence of the nasal edge of the graft can also occur. This requires no reintervention as long as the graft shows no significant displacement.

Removal with AM Graft Placement

This technique of pterygium and amnion placement does not use the conjunctival autograft. Amniotic membrane, the surface membrane of the human placenta, has long been used in ocular surface surgery because of its well-documented anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties. Amnion is available from two sources in the

Amniotic membrane has a basement membrane surface. In pterygium applications, it's best to leave this basement membrane on top, away from the sclera. With the AmbioDry, the basement membrane side is easily identified. The basement membrane side is facing the surgeon when he can read the letters "IOP" embossed on the graft. In BioTissue's product, the basement membrane side is on the top surface opposite the cellulose paper on which the amnion is mounted. Surgeons can confirm this by using a cellulose sponge on the surface of the AmnioGraft. You will find that the stromal side is stickier than the basement side.

In this technique, I place mitomycin 0.025 percent on small pledgets in the subconjunctival space surrounding the excision site and remove them after one to three minutes, depending on the size and aggressiveness of the pterygium. It is important to avoid exposure to bare sclera. Once I remove the pledgets, I rinse the application area copiously with BSS.

As with the conjunctival autograft, our group's recurrence rate with this technique is less than 1 percent. The advantage of this technique is that it does not require surgery at a second site, where an autograft is harvested. This autograft site can complicate future glaucoma surgery. We have also found greater patient comfort without an autograft, and the cosmetic appearance, particularly in the early postoperative period, is better than an autograft, although the long-term results are similar.

Again, I excise the pterygium from the cornea and the conjunctiva and open the surrounding subconjunctival potential space using blunt dissection with MacPherson forceps. This creates a potential space for the amniotic membrane. Next, I cut the amniotic membrane within its surgical packaging to the appropriate size. We prefer Ambio5, the thickest type of human amniotic membrane because it allows ease of placement and remains on the ocular surface for at least several weeks following surgery.

It is important to place the amniotic membrane at least a few millimeters beneath the surrounding conjunctival tissue because the fibroblasts that can lead to recurrence reside in this area. This amniotic membrane will stay in place for many weeks, exerting its antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects long after the patient has discontinued the eye drops.

For the next step, I place fibrinogen sparingly on the ocular surface and apply the amniotic membrane, tucking it into the subconjunctival space by several millimeters. I complete the graft placement by applying thrombin on top. It is unclear how much of this thrombin mixes with the fibrinogen beneath the graft. Some surgeons don't use thrombin at all in this technique because they feel that the eye's blood supply provides ample native thrombin to facilitate polymerization and graft adhesion.

Postop management is similar to that with an autograft: prednisolone and a fluoroquinolone q.i.d. as well as a topical NSAID.

The Combined Approach

The combined use of a conjunctival autograft and placement of amniotic membrane is usually reserved for high-risk cases that involve larger or inflamed pterygia or pterygia that are likely to recur, especially those that have been previously excised.

In this technique, I excise the pterygium as in the other techniques and harvest a conjunctival autograft from the superior limbus. However, the autograft is left attached at the limbus until later. Next, I open the potential space beneath the surrounding conjunctiva and cut the amniotic membrane in a C shape to conform to the surrounding tissue. Using non-toothed forceps, I tuck this graft into the subconjunctival space. For this application, I favor the human amniotic membrane of 50-µm thickness (AmbioDry), which is ideal for cutting and handling and allows the graft to remain quietly in the subconjunctival space for many months following surgery.

Placing the amniotic membrane in the subconjunctival space is fairly straightforward. Keeping all sides of the amniotic membrane with the basement membrane side up is not essential. The amniotic membrane is acting mostly as a depot of anti-inflammatory activity, so its orientation does not matter. The surgery concludes with placement of the conjunctival autograft in a technique identical to that of the other procedures.

Postoperative management follows that of the previously mentioned procedures: patch and shield overnight, prednisolone and a fluoroquinolone q.i.d. and an NSAID as directed.

Potential Complications

Fortunately, the complications with all these procedures are rare and easy to manage. In about 1,000 procedures by our group, only one graft was lost, and four required resealing. In younger patients, the most common complication is pressure spike following steroid use. Watchful waiting is appropriate.

With the autograft, some dehiscence of graft from the host conjunctiva, usually on the nasal side of the cornea, may occur. This is usually well-tolerated and doesn't need to be surgically addressed as long as the graft is secure so it will heal together. A large dehiscence or partly displaced graft may require additional adhesive.

Today, even patients with the most severe pterygia have many options. Cornea specialists who treat the most aggressive forms of the disease are relying more on these three techniques. Some feel strongly about the use of amnion, some about the use of the autograft only. I've had good success combining the two techniques. The autograft works best on the surface of the defect, and the amnion works best under the surrounding tissue.

Dr. Hovanesian is a clinical instructor at the UCLA Jules Stein Eye Institute in

1. Koranyi G, Seregard S, Kopp ED. Cut and paste: A no suture, small incision approach to pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:911-914.