Staff Matters

Physicians who have conducted clinical trials say that the volume of documentation, organization and attention to detail involved in running a trial put new demands on your current staff, and almost certainly will require you to hire someone new, as well.

“Such tasks as fulfilling regulatory requirements, documenting things systematically, making sure everything is done by the book, ensuring that [Institutional Review Board] approval is secured correctly, making sure the patient has signed all the consent forms, ensuring the informed consent is properly documented, seeing to it that everything is dated and timed properly and that all personnel are correctly certified—that involves a tremendous amount of paperwork and is really a skillset unto itself,” declares Sunir Garg, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Garg has had experience as a principal investigator in several clinical trials in retina. “If an ophthalmologist were new to clinical trials, having a clinical trials coordinator or research personnel with some experience with research and regulatory documents isn’t just helpful—it’s critical,” he says. “Each patient who comes in for the trial will fill two three-ring binders by the end of the study. If you try to do it all by yourself out of the gate, it will be very hard to do.

|

| Gene therapy subject Richard Chandler discusses the details of his upcoming operation with surgeon Robert MacLaren at the University of Oxford. (Image courtesy Robert MacLaren, FRCOphth, FRCS.) |

BethAnn Hibbert, clinical study coordinator for The Cornea & Laser Eye Institute in Teaneck, N.J., says first-time clinical investigators are also often caught flat-footed in terms of general staff training. “Another thing that’s critical in terms of your documentation is staff training in good clinical practices that ensure subjects’ safety and data integrity,” she says. “It’s important to understand that any staff involved in research that involves human subjects needs to undergo training. This training is sometimes available through your IRB but it can also be done online, as well. The service we use is the online Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative at the University of Miami. Additionally, this staff training needs to be updated every two to three years to ensure and document that all your staff involved with trials are adequately trained in subject protection. This training is important, and it’s one of those things that may not be noted for physicians when they get into research, since some sponsors assume your staff has this training and may not make it known that it’s needed.”

This staff training touches on such things as the management of the informed consent process and protecting the privacy of subjects in terms of how their records are kept on-site. “The staff should have a working knowledge of the protocol, including any procedures that are going to be performed, the study’s purpose, risks and benefits and subject selection criteria,” says Mrs. Hibbert, who adds a tip for practices embarking on clinical trials: “What we do here is keep a kind of cheat sheet for each of the studies in which we’re participating. These sheets have a breakdown of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and the diagnostic tests that are required at each visit, to ensure that we didn’t overlook anything and to reinforce the staff training in the protocol, because sometimes it’s a lot of detail to keep in your head.”

Even though the physician may be used to anticipating problems and taking corrective action in the day-to-day clinic, experts say being in a clinical trial requires even more on this front. “If some of your study staff aren’t experienced in performing clinical trials, it can help to simply develop a really strong manual of standard operating procedures that breaks down every aspect of the study,” says Mrs. Hibbert. “It’s kind of like a bible for you to follow. It covers everything, from the process of informed consent and the maintenance of the regulatory files to the process of reporting adverse events.”

Though ophthalmologists may feel their staff is capable in a standard clinic, they have to drill deeper and make personnel decisions with a different set of criteria in mind when they get into a trial and have to assign staffing duties. “For the research staff, I’d choose some of the better, more detail-oriented techs,” advises Dr. Garg. “Choose some folks who are maybe more curious in terms of new treatments and treatment options, because patients will bring up a lot of questions regarding the trial or diseases in general. Even after subjects have been in a trial for 18 months, they will sometimes ask, ‘Why am I in this trial again?’ Having a staff that’s able to field such questions is helpful, not only for keeping patients motivated but also to free up the doctor so he can focus on patient care in the regular practice and not just in the research unit.”

Patient Discussions

Doctors and trial experts say that many of the patient discussions before and during a clinical trial are different from those in the everyday clinic. The ophthalmologist hasto have a different approach and thought process, because patients can be coming at the trial from different points of view, depending on their disease state and the efficacy of their current medications.

Robert MacLaren, FRCOphth, FRCS, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, is currently researching stem-cell therapy for retinal disease, an electronic retinal implant and a new intraocular lens. He says it’s important not to lose sight of the patient’s perspective when embarking on a trial. “The patients are very important because you need to have the right people,” he says. “If you’re dealing with patients with incurable disease, which, unfortunately, I am on a daily basis, they are very keen to do almost anything to help, but can sometimes misinterpret ‘trial’ for ‘treatment.’ It’s very important to remind patients at every stage of the trial that they’re taking part in a clinical trial with unknown risks. It’s not a treatment. Sometimes, we actually won’t recruit a patient because even though he really wants to be in the trial, he doesn’t understand what we’re trying to achieve with it. He assumes it’s actually a treatment.”

|

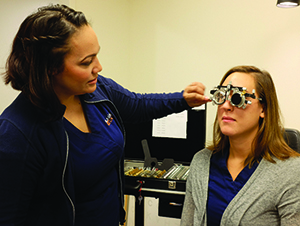

| Be prepared for extensive, time-consuming testing in a clinical trial, experts say. (Image courtesy Sunir Garg, MD.) |

“A second difference is the time involved,” Dr. Garg continues. “When you’re in a really busy clinic and are two hours behind schedule, many times your general bias is to treat someone fast and get him on his way so you don’t fall further behind. But when you’re involved with a research trial, the discussion about the trial, getting patients interested in it, talking to them about potential pros and cons—that all takes time. In the middle of a busy day it can be hard to be motivated to have that discussion. However, if you’re invested in the clinical trial process, that’s the kind of conversation you need to have, because if you’re not willing to take the time to discuss with patients why they might be interested in doing something different from the standard, they’re simply not going to be interested in the trial.”

Physicians say motivation can be an issue for some patients, since they may not see the need to enter a trial. “If the patient has a disease from which he knows he’s going to go blind, and you’re known to be doing research in that field to try and find a treatment, he’s going to be the most helpful and accommodating person you could ever want in a clinical trial,” says Dr. MacLaren. “But if he has a condition that causes a problem with his eyesight but you’re actually investigating him for some other reason, or he has no obvious benefit from what you’re doing in the trial, then he won’t be nearly as motivated. This is understandable, given the commitment he has to make. However, in such a case, there may be an indirect benefit to the patient that he may not be aware of, so you may wish to give him more information about that. For instance, in a glaucoma clinic, patients may be perfectly happy with the drop that they’re on, but you want them to come in and try a new one in a study. They may not like this, and in response you can say, ‘Well, the time may come in a few years when you’ve become tolerant or intolerant to your current drop, and we might need to change them round or add one to your current drop. By getting these new drops approved with the trial, it might help you indirectly later on.’ They need to be aware of that possibility.”

Mrs. Hibbert says the clinical trial informed consent process that these patient conversations comprise is much more involved than the consents doctors might be used to. “Something that’s not necessarily obvious to a practice starting out in clinical trials is the need to document the whole informed consent process,” she says. “With a clinical trial, it’s not sufficient to just have an informed consent document that’s signed; you also have to document the process that surrounds the signing. When you’re in research, if you’re subjected to an investigation by the FDA or a sponsor, the informed consent documentation is the first thing they look at. In practice, after a subject has had the opportunity to review a consent document, we’ll document the discussion of the consent. A tip we learned from an internal audit is to have the subject read through the consent and then ask him, ‘Why do you want to participate in this study?’ and then document key parts of the discussion that follows. You want to document that the subject truly understands the nature of the research and that he has realistic expectations of what participation would provide for him.”

Jumping Through the Hoops

As Dr. Garg alluded to in his discussion of the need for a clinical coordinator, one of the most pronounced differences between everyday practice and a clinical trial is the vast amount of contemporaneous documentation that’s required. When this documentation is coupled with the rigorous regimentation of clinical trial patients’ exams—which can last hours—the ophthalmologist is forced to adjust his approach to his daily schedule. Here are the key areas to be aware of:

• Regimented visits. “There are so many differences between a well-run clinical trial and just taking care of patients in terms of the amount of documentation and structure that are required,” says Doug Koch, MD, professor and chair of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “It affects everything, from scheduling to testing to patient questionnaires and so on, that it requires a very different mindset, and not a mindset that’s always oriented toward the best patient care and certainly not toward efficiency. For instance, in a normal clinic protocol, if a patient is doing great one-day postop, you might just have him come back in four weeks. But what if the trial protocol requires patients to come back at two weeks? What do you do with that? A protocol may also require best-corrected acuity refraction for near, medium and distance, performed in various lighting conditions which you need to gauge, and performed by the same person each time, with a certain type of eye chart. That’s way out of bounds for what a good-quality private practice situation—or any kind of private care—for a patient would entail.

“It’s ultimately oriented toward patient care because you’re trying to create new science, but it’s a very different system for a practice,” Dr. Koch continues. “However, if the trial starts cutting into efficiency and the care you’re giving to other patients, everyone will start to bail on it psychologically and physically. You have to have a good system so you can fit the trial into your schedules and still retain the initial enthusiasm throughout the trial.”

Teaneck, N.J., cornea specialist Peter Hersh, who has participated in a number of clinical trials and is currently the medical monitor for Avedro’s U.S. cross-linking studies, says you may need to set aside an exam room that’s specially prepared for your clinical study, as well as arrange for special staffing needs. “In refractive surgery studies, the patients require multiple refractions, masked refractions by masked observers who haven’t seen the patient before and corneal topography,” he says. “A lot of measurement needs to be done at each visit, so these tend to be lengthy visits. You need study personnel who know the patient and study personnel who don’t know the patient, if you’re dealing with masked observer requirements. At our site, our optometrist will do the masked refractions because he’s otherwise not involved with the trial.

“Often, you’ll need to dedicate a specific exam room with specific lighting conditions so you have reproducible tests,” Dr. Hersh continues. “You can’t take patients from one exam room to another because the lighting conditions can change from room to room.”

Norfolk, Va., ophthalmologist Elizabeth Yeu, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, says the extra testing required for trial patients may require you to re-evaluate your scheduling. “Setting aside a block of time for clinical trial patients can work,” she says. “Also, you can have them come in on your clinical coordinator’s schedule, so you can just go in and do your part. In one study, we had trial patients come in on a Saturday morning to enable us to complete all the exams at once.”

Dr. MacLaren says, in some cases, you may need to dust off your negotiator hat. “I’m always negotiating with commercial sponsors and asking them to stop doing all of these tests,” he says. “They always tend to overcook it because they don’t realize how difficult it is to run everything on the ground. I joke with my staff that they overload the patients with so many investigations that when they leave the clinic someone here realizes he never checked the patient’s visual acuity. It’s always better to do fewer tests, generate test readings that are more reliable and have more motivated patients than to overload patients and your staff.”

|

| It helps to have a trial coordinator to manage a study’s heavy documentation. (Image courtesy Sunir Garg, MD.) |

• Extensive documentation. In addition to the obvious need to document patient exam results, the ancillary documentation requirements might surprise the first-timer. “Any investigational product on-site has to be carefully monitored,” explains Mrs. Hibbert. “Early on, we weren’t aware that we had to document the fact that we were maintaining temperature logs for trial drugs. You can’t just write that the drug’s temperature range is normal, you need trackable records of the temperature showing that it’s been maintained throughout the day. Shipments of products have to be carefully logged, and any shipping invoices that come with the product have to be retained in the regulatory binder. You have to document your staff’s training, and any changes in study staff and the fact that they were trained also need to be documented. This way, if you have to go back and look at something in the binder, the whole process reads like a story.”

• Adverse event reporting. Physicians say ferreting out adverse events and properly reporting them can be a challenge at first. “Understanding how adverse events are reported is quite complicated,” says Dr. MacLaren, who notes that this particular function took the most getting used to when he did his first clinical study. “You have a certain amount of time to report an adverse event, and requirements regarding who you report them to. If you have an adverse event, you need to know quickly what to do. That’s probably one of the most complicated parts of the process: knowing what to do if a patient suddenly reports an adverse event or gets admitted to hospital.

“You have to report all adverse events,” Dr. MacLaren continues, “because you don’t know if that particular adverse event is related to the drug or not. The only way you can tell that is by repeatedly seeing more adverse events that are similar coming up amongst study patients. A good example is ciprofloxacin. No one could have assumed that someone straining his Achilles tendon was due to him taking an antibiotic. But it was only when several instances of Achilles tendon injuries occurred that clinicians realized that this was something that was related to the drug. It’s now a known adverse reaction to ciprofloxacin. In ophthalmology, we really don’t have such an issue—but you never know. So you document it.”

Mrs. Hibbert says you sometimes have to fish for an adverse event that might turn out to be relevant. “You and your staff have to be of the mindset to ask the subject, ‘How are you feeling? Has anything changed since you were here last?’ ” she says. “The subject won’t necessarily report something to you because he might not think it’s related to the treatment, so you have to prompt him. Ask about patients’ general health and any medication that might be new. These may prompt red flags for reportable events.”

In the end, Dr. MacLaren says proper preparation, mentally and in your facility, can make the most of the clinical trial experience. “There are those patients who have no treatment available for their disease,” he says. “They are going blind and you can offer them a trial that may help them preserve their vision, and this is a tremendous opportunity for them to get involved with. First, however, you have to be motivated by the research and the notion of understanding the disease better and helping your patients. Research is a long-term treatment, not a short-term one, so you need to ask yourself: Do you really want to do this?” REVIEW