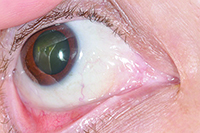

Given the patient’s personal history of previous B-cell lymphoma, recurrence of a malignant lymphoma in the conjunctiva was considered. Due to the nonspecific features of the lesion, the differential also included benign conjunctival masses such as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphangioma, or atypical inclusion cyst. Additional malignancies considered in a patient on chronic immunosuppression include Kaposi’s sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma and amelanotic melanoma. An infectious etiology or inflammatory condition was much lower on the differential diagnosis due to the lack of related features on examination.

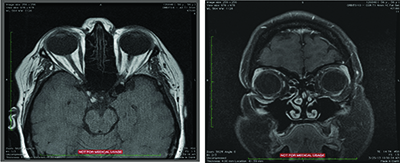

MRI of the orbits was subsequently performed and was largely unremarkable. The globes and optic nerves were normal bilaterally, without abnormal enhancement. The extraocular muscles and orbital fat were unremarkable without evidence of inflammation. There was no discrete intraconal or extraconal mass. The ventricular system and cavernous sinus were normal.

Laboratory evaluation with complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were both unremarkable. Without evidence of orbital tumor on MRI and largely normal lab work, the patient underwent biopsy of the right medial canthal lesion. A 15 mm x 15 mm x 4 mm salmon-colored specimen was submitted to pathology. Histopathology revealed a follicular lymphoma, grade 1 to 2/3 with a mixed follicular diffuse growth pattern (50 percent follicular and 50 percent diffuse). An orbital specimen was negative for tumor.

Given the patient’s localized findings of a conjunctival follicular lymphoma, the patient was then treated with eight weekly infusions of rituximab, a monocolonal antibody that targets CD20+ B-cell lymphocytes. Rituximab has been approved as a first-line treatment for indolent, isolated orbital adnexal lymphoma.1 The patient tolerated the treatment without serious systemic side effects with resolution of the right conjunctival lesion (See Figure 3).

|

Discussion

This patient had been diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis in 1998 and was subsequently started on methotrexate and oral prednisone. The symptoms persisted despite this regimen, and consequently etanercept (Enbrel), a tumor necrosis factor antagonist, was added to her treatment. She used this medication for nine years without any complications. In 2009, she developed lymphadenopathy in her neck and right periorbital region. Biopsy revealed the presence of Stage IIA follicular B-cell lymphoma, a subset of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Etanercept and methotrexate were both discontinued immediately, and the patient was treated with rituximab for four consecutive weeks and a maintenance therapy of every month for two years.

Etanercept belongs to a class of drugs known as disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), injectable biologic agents that function by suppressing the body’s immune system. Etanercept was first released for commercial use in 1998. The Food and Drug Administration approved indications for this medication include rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. When patients are symptomatic despite the use of first-line anti-rheumatic medications, such as methotrexate, physicians often turn to biologic agents as the next course of therapy. DMARDs generally provide rapid onset of action and less-frequent dosing. However, this needs to be balanced against possible correlation between the use of biologics such as etanercept and the development of lymphoproliferative disorders.

|

A major caveat to consider in these two studies, however, is the fact that patents with rheumatoid arthritis are inherently at a higher risk of developing malignant lymphoma. According to a 2003 study, the overall risk for lymphoma in RA patients is doubled compared to non-RA patients.4 This is compounded by the fact that there is a strong association between severity of inflammatory disease and the risk of developing lymphoma. TNF antagonists and biologic agents in general tend to be given to patients with more severe disease. This same inherent risk, on the other hand, was not found between ankylosing spondylitis and the development of lymphoma according to a 2006 retrospective case-control study performed in Sweden. Using the Swedish Cancer Register, Johan Askling, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no evidence to suggest that the average risk of lymphoma in patients hospitalized with ankylosing spondylitis is increased.5

This patient with ankylosing spondylitis received etanercept for nine years before developing follicular B-cell lymphoma that was detected in 2009 and recurred again in the conjunctiva in 2013. A similar case report was published in 2011 of a 45-year-old Turkish male with ankylosing spondylitis who developed diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after 11 months of etanercept therapy.6 Etanercept was discontinued and his cancer went into remission after receiving systemic chemotherapy.

In conclusion, there is growing evidence of a potential positive correlation between the development of lymphoma and the use of TNF antagonist biologic agents. Although it is impossible to point to etanercept therapy as the sole cause of lymphoma in this patient, it is important to raise awareness that patients on these medications could be at greater risk for lymphoma. Therefore, we must encourage physicians to use their best judgment when treating chronic inflammatory conditions with administration of TNF antagonists. REVIEW

The author would like to give special thanks and acknowledgement to Carol Shields, MD.

1. Stefanovic A, Lossos I. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Blood 2009:114.3;501-510.

2. Brown L. et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Therapy and Lymphoma. Arthritis Rheum 2002:6;2;3151-3158.

3. Wong, A et al. Risk of Lymphoma in Patients receiving Antitumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clinical Rheumatology 2012:31;631-636.

4. Ekstrom K, Hjalgrim H, Brandt L, et al. Risk of Malignant Lymphomas in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and in their first-degree relatives. Arthritis Rheum 2003:48;963-970

5. Askling J, Klareskog L, Blomqvist P et al. Risk for malignant Lymphoma in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Nationwide Swedish Case-Control Study. Rheum dis 2006:65;1184-1187.

6. Asku, K. et al. Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma following Treatment with Etanercept in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Rheumatol Int 2011:31;1645-1647.