Thanks in large part to the 2011 report from the International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction, sponsored by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society, interest in the connection between meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye has increased noticeably. The report, which took more than two years to complete and involved input from more than 50 dry-eye experts around the world, attempted to correct several perceived oversights in this area. Among other things, despite the worldwide prevalence of meibomian gland dysfunction, there was no commonly accepted definition of the disease or agreement about diagnosis, classification or therapy.

The workshop offered the following as a formal definition of meibomian gland dysfunction: “a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands, commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/quantitative changes in the glandular secretion.” Although low or absent delivery of the secretions is most commonly seen, the report notes that excess secretion can also occur. In either case, the result of these changes can be alterations of the tear film, symptoms of eye irritation, inflammation of the ocular surface and dry eye. (Links to summaries of the report, as well as the full report, can be found at

tearfilm.org.)

Shifting Clinical Focus

Penny A. Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA, professor of ophthalmology and director of cornea and refractive surgery at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, believes the report represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of dry eye. “Health professionals have now been alerted that lid disease can be a major contributing factor in ocular surface disease,” she points out. “As a result of this report, ophthalmologists are now evaluating the lids more carefully and more often when seeing patients with dry-eye complaints.”

Dr. Asbell notes that in the past, doctors were thinking more about an abnormal tear film, primarily relating to low tear volume from aqueous-de-ficient dry eye. “Their primary concern was increasing the volume or quality of the tears,” she says. “This is still perfectly reasonable and important to consider in someone with ocular surface disease, but a lot of the problem with the tear film may actually stem from lid disease rather than simple aqueous deficiency. It isn’t a new idea, but the report coalesces the data to support that line of thinking.

“In the past, there’s been a lack of data on meibomian gland disease, reflecting a general lack of interest in this area,” she continues. “For example, when we did the study of cyclosporine that led to Restasis eye drops, we looked at the lids as part of the clinical trial, but only briefly and not with a lot of intense interest,” she says. “It wasn’t a focus of the trial. That’s one reason there’s not as much data about meibomian gland disease as we’d like; most previous studies didn’t worry much about analyzing lid findings, and very few trials have looked at lid disease directly. So, we’re still at the beginning of the process of understanding meibomian gland disease, and seeing what, if anything, helps to improve it. Hopefully, going forward, the new level of interest generated by the report will result in new data about the natural history of the disease, how common it is, and how and when to treat it.”

The Nature of the Disease

“Inspissation of the meibomian glands is very common in the United States, although studies suggest that it may be even more common in some Asian populations,” notes Jay S. Pepose, MD, PhD, medical director of the Pepose Vision Institute and professor of clinical ophthalmology at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “Meibomian gland disease is probably the main cause of dry eye—certainly of evaporative dry eye. Of course, dry eye can be a mixed disease, where you have some aqueous deficiency component and some evaporative component.”

|

“You can look at meibomian gland disease from two perspectives,” says Steven C. Pflugfelder, MD, professor and director of the Ocular Surface Center at Baylor College of Medicine’s Cullen Eye Institute. “One is that it’s an eyelid problem. There are people whose lids become inflamed as a result of meibomian gland disease. However, not a whole lot of people come in complaining about that. Most people who have meibomian gland disease—or those in whom it appears to be the cause of their problem—come in because they have a tear dysfunction and they’re starting to get corneal or conjunctival disease. The nerves on their corneas are being stimulated, so they’re sensing irritation, or their vision is getting blurred. In that case, it’s more of a tear dysfunction problem.”

Dr. Pflugfelder adds that when meibomian gland disease is present, it does seem to affect tear stability. “In many people it appears to cause conjunctival redness, irritation and corneal epitheliopathy—particularly in the lower cornea,” he says. “We know that the eye gets inflamed, because if you sample the tears at the ocular surface there are higher levels of inflammatory mediators and proteases in many of those patients. And there are probably a lot of other things going on that we don’t know about.”

As for what causes the meibomian glands to malfunction, Dr. Pepose says multiple factors may be to blame. “Some people think androgens like testosterone play a role in maintaining normal meibomian gland function,” he notes. “I’m sure that fatty acid metabolism plays a role, not just in maintaining the gland function, but also in altering the constituents of the secretion. The proper balance of elements like polar lipids and waxy esters in the secretion help to keep the tears from evaporating.”

Conducting the Exam

A number of strategies during the examination process can help ensure an accurate diagnosis:

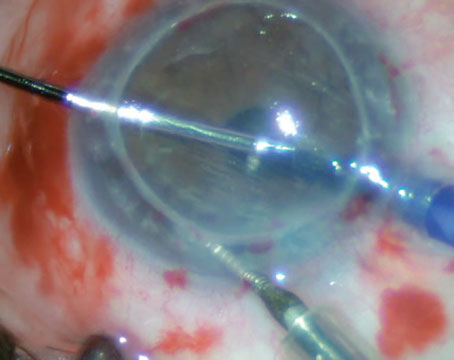

• Always examine the eyelids and express the glands. “I think examining the eyelids is a requisite part of any examination,” says Dr. Pepose. “If you don’t express the lids, you’re not getting the information you need: Does the patient have inspissated or functioning meibomian glands? If you manually express the glands, you can judge or grade their ability to secrete meibum.

You could find a clear secretion, which is normal, or an opaque secretion, which is not normal. (See example, above.) Or, the glands could be completely blocked—no secretion at all. So there are different stages of meibomian gland disease.”

|

Dr. Asbell says that when a patient presents with complaints that sound like ocular surface disease, in addition to doing a Schirmer’s test, ocular surface staining with fluorescein and lissamine, and checking tear-film breakup time, she does a thorough lid evaluation. “Evaluating the lids means more than just looking at them at the slit lamp,” she says. “It means putting a little pressure on them to see whether the meibum that’s secreted is normal or abnormal. Doctors are starting to make this part of their regular exam and making decisions based on those findings. That’s actually a big change; for many clinicians this was not routine before the report came out. People weren’t looking at the lids too closely, unless the patient had a real complaint or there was obvious inflammation.”

Dr. Asbell notes that to examine the lids you need to pull them back using your finger or a tool such as a Q-Tip. “The edges of the lids where the orifices for the meibomian glands are located point toward the ceiling or floor, so to get a look at them you have to pull the lids away from the eye a little,” she says. “You then turn the edges toward you by everting the lids a little bit. This is important because the lids may look normal, but when you put some pressure on them you may discover that the meibum looks quite abnormal. This is what Donald Korb, OD, FAAO, describes in the workshop report as ‘non-obvious MGD.’ ”

Dr. Asbell adds that there’s no easy way to distinguish between minimal production of meibum and blockage of the outflow channels. “That’s a subtle distinction, because the glands are within the lids,” she points out. “All we can do is check to see whether meibum is coming out. As the glands make meibum, it’s normally pushed out to the surface. If a gland becomes obstructed so the meibum can’t get out, the gland tends to degenerate and stop functioning altogether, leading to minimal or nonexistent production.”

• Remember that hypersecretion can be equally problematic. Dr. Asbell notes that one way a meibomian gland problem can manifest is through hypersecretion. “You sometimes see people with a sort of foam along the edge of the lids, indicative of increased meibum secretion,” she says. “On the other hand, you see people who don’t produce any meibum at all, even with increased pressure from your finger or a Q-Tip. Are these different stages of the same disease, or different etiologies leading to different endpoints? I’m not sure we know the answers.”

• Check for aqueous deficiency. “When examining these patients, my primary interest is in determining whether there’s an aqueous deficiency or normal aqueous production and volume,” says Dr. Pflugfelder. “If there’s an aqueous deficiency, that might require a different treatment approach than if I find a normal amount of aqueous production. I’d say that 95 percent of patients who come in having trouble, but with normal aqueous, have meibomian gland disease.”

• Use retroillumination to check the number of glands. “It’s possible to see the glands by using retroillumination during the lid exam,” notes Dr. Asbell. “There are 30 or 40 glands in the upper lid and 20 to 30 in the lower lid. If a patient has severe meibomian gland disease, you can actually see that some of the glands are no longer present. Losing one or two probably isn’t significant, but losing a lot of them can be.”

• Don’t assume patients will voluntarily mention their symptoms. “I’m more proactive and aggressive about assessing the meibomian glands if a patient is symptomatic,” says Dr. Pepose. “But patients sometimes don’t volunteer their symptoms. You may have to elicit this information from them using directed questions. It may be that they’ve reached a point where they are hypesthetic, or the symptoms are so chronic that they think they’re normal findings. If you ask a patient, ‘Are you having problems?’ he may say, ‘I’m fine.’ But if you ask whether he has fluctuating vision during the day, he may say yes. He may admit that his eyes feel irritated, that he has a foreign body sensation, or that his eyes often feel dry—if you ask him directly.”

• Ask whether the symptoms are worse in the morning or evening. “Many patients with meibomian gland disease say that their eyes feel worse when they first wake up,” notes Dr. Pepose. “That’s different from patients with aqueous deficiency dry eye, where they almost always get worse as the day goes on.”

• Consider having new patients fill out a dry-eye survey. “Because we’re a specialty practice focusing on cornea, refractive surgery, external disease and cataract, we routinely give new patients a dry-eye survey,” Dr. Pepose says. “That tells us right away if the patient is symptomatic; it helps us to direct the exam.”

• Consider checking tear osmolarity. “I think tear osmolarity is important because it’s a consequence of having a lipid deficiency,” Dr. Pepose says. “If your tears are evaporating, your tear film will become hyperosmolar. Testing osmolarity provides another important clue.

|

“Of course, hyperosmolarity doesn’t tell you if the patient has meibomian gland disease or an aqueous problem, because osmolarity is elevated in all forms of dry eye,” he adds. “But it’s unusual to find a patient with normal tear osmolarity who has a dry-eye problem. If osmolarity is normal, you’re probably safe focusing your attention elsewhere.”

Dr. Pflugfelder notes that the new tests that measure matrix metalloprotease 9 and osmolarity of the tear film could both be useful when trying to measure meibomian gland disease. “Both factors increase when meibomian gland disease is present, so these tests might help us in the clinic,” he says. “For example, doxycycline is a potent inhibitor of MMP-9. So it makes sense that if people have high levels of MMP-9, they might be candidates for doxycycline. Corticosteroids also inhibit MMP-9 production.” (The Inflammadry test to measure MMP-9, produced by Rapid Pathogen Screening in Sarasota, Fla., has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.) Other devices designed to quantify the tear film as an aid to dry-eye diagnosis include the LipiView Ocular Surface Interferometer from TearScience (Morrisville, N.C.). (For more on these instruments, see the article on p. 38.)

Treating MGD

Options for treatment remain limited, but each one seems to help some subset of patients:

• Warm compresses, massage and hygiene. Dr. Asbell says her primary treatment for MGD is still mainly lid hygiene. “That consists of warmth applied to the lids to loosen up the meibum, along with lid scrubs,” she explains. “The lid scrubs may be prepackaged, but in some cases patients prefer to create their own lid scrub using baby shampoo with a cotton ball or something along those lines.”

Dr. Pflugfelder notes that many of the patients he sees are beyond the point of no return. “They don’t have any glands left, or the ones they have aren’t functioning,” he says. “For them I believe heating and massaging won’t do anything. There will be a subset of people who still have functioning glands, and heating and massaging will cause some glandular secretion to make it onto the ocular surface. At least, I think so. We need a rigorous clinical trial to confirm that this actually happens.”

• Lipid-based artificial tears. “If the patient has significant shortening of the tear breakup time, meaning the tear layer is not uniformly covering the ocular surface, then I’ll add an artificial tear as well,” says Dr. Asbell. “Some artificial tears are now targeted toward managing meibomian gland dysfunction; they’re made with a more lipid base to replace factors that may not be being produced sufficiently by diseased meibomian glands.”

• Antibacterials and nutritional supplements. Dr. Asbell notes that one factor that may contribute to pathology is normal bacteria such as staphylococcus breaking down the fatty components of the meibum into free fatty acids. “Free fatty acids can contribute to lid irritation and changes in the ocular surface,” she points out. “Systemic doxycycline can interfere with the lipases that break down some of the fatty components. So, after I try lid hygiene and artificial tears, if the patient is still symptomatic I may switch the patient to a systemic product such as doxycycline or tetracycline.

“Doxycycline has been used successfully for treating skin problems such as acne and rosacea for years,” she points out. “I might also consider using a topical antibiotic such as bacitracin as a way to reduce the overall volume of bacteria. The idea is not that this constitutes an infection, because there are always bacteria on the lid. There may just be too many microbes, or the type of microbe present may lead to more fatty acid breakdown.”

Dr. Pflugfelder notes that doxycycline, topical steroids and nutritional supplements like fish oil and gamma-linolenic acid may all help some patients. “Doxycycline hasn’t had a masked clinical trial, as far as I know, but corticosteroids have been tested, as have the nutritional supplements,” he says. “Those do show improvement at least in symptoms and maybe in signs. Because there’s some evidence-based validity to prescribing those three therapies, I tend to favor them. And I have seen some improvement in eyelid redness with these treatments. I’ve also seen improvement with topical azythromycin, although it hasn’t been subjected to a randomized clinical trial. However, I can’t honestly say that the meibomian glands function any better as a result of these treatments.

“Unfortunately, at this point, my treatment is still geared to decreasing inflammation on the eye, because I don’t have any treatments that will really improve the meibomian gland disease,” he adds. “I’m not even convinced that improving meibomian gland function will help these patients that much.”

The High-tech Approach

As more attention has been devoted to meibomian gland dysfunction, new approaches to treatment have begun to appear. “The company TearScience in North Carolina has developed the LipiFlow device, which covers the lids and heats and massages them, with the goal of making them function more normally for some period of time,” Dr. Asbell notes. “The procedure is FDA-approved, but insurance doesn’t cover it, and it’s expensive; the device costs about $100,000 and the disposable eye cups for each use cost about $650 a pair. At this time, the patient has to pay out of pocket. I have minimal experience with it, but I know some ophthalmologists swear by it. I think it’s too early to know how this will end up fitting into the treatment picture.”

|

“Warm compresses apply heat to the outside of the eyelid, the opposite side from the meibomian glands—and you have a vascular structure on the outer lid that picks up some of that heat and carries it away,” he continues. “With the LipiFlow system, the heat starts on the inside. The interface locks around the eyelid, with the heating element on the inner aspect, closer to where the meibomian glands are. The device heats up the meibum and then mechanically massages open the glands.

“Ultimately, of course, you have to select the right patients,” he notes. “This device can be very useful, particularly in individuals in whom the secretion resembles toothpaste. They have to have some glands that are expressing. I wouldn’t treat patients who are not symptomatic and have no complaints, or patients at the opposite end of the spectrum, where you put pressure on the meibomian glands and there’s no expression at all. But I think there is a role for LipiFlow in the patients who still have some secretion from the glands.”

Dr. Pepose admits there are limits to what the device can accomplish. “Like any treatment, I don’t get a 100-percent response,” he says. “And I have to explain to people that it’s not a forever treatment; it seems to be effective for nine to 12 months, maybe a little beyond in some patients. So they probably will require retreatment, because we’re not addressing the underlying cause of the problem. Also, the system may reduce but doesn’t necessarily eliminate the problem in patients who have been suffering for many years, so we explain to patients that this is an adjunct; they may still need to use other approaches, such as occasional drops. And cost is a barrier for many patients. It’s an expensive device, and every time you use the device you have to pay for the interface. Unfortunately, at this point in time it’s not a covered service.

“On the other hand, many of these patients have been on tetracycline; they’ve tried warm compresses; they’re already taking omega-3s and using tear drops with lipid substitutes or serum tears,” he notes. “They’ve gone full spectrum and they’re still unhappy. Many of them feel that the opportunity to improve their quality of life is worth paying for the treatment. And in my experience, the vast majority of patients do respond to this. A lot of patients have told us that, unlike anything they’ve tried before, this gave them some relief. People have told us that for the first time in months they could go through the day without thinking about their eyes. For them it was worth it.”

Dr. Pflugfelder is more skeptical regarding how helpful this kind of approach is, high-tech or not. “Even when the meibomian glands aren’t good and I recommend warm compresses and lid massage, at best that leads to a 30- to 50-percent improvement,” he says. “Many patients aren’t helped at all, and it’s a lot of effort on their part. In fact, a lot of the support for using warmth and massage is anecdotal.”

Asked about the studies showing the LipiFlow device was efficacious in 86 percent of MGD patients, he notes that those studies were limited in their scope. “There are no controlled, randomized clinical trials proving that this approach is superior to placebo,” he says. “I’m sure it does help some patients, but the clinical data showing which patients it helps is lacking. In the meantime, many of these patients are very uncomfortable and desperate for relief, so they’re often game to try anything.”

The Asymptomatic Factor

Dr. Asbell notes that there are a host of questions about meibomian gland dysfunction that remain unanswered. “Many patients seem to develop meibomian gland disease as they age, so it may be partly an age-related phenomenon,” she says. “We also don’t always find a direct correlation between a meibomian gland problem and patient symptoms. Some of these patients clearly have meibomian gland disease, but they’re not symptomatic at all.

|

Dr. Pepose agrees. “Thirty percent of dry-eye patients don’t have any symptoms but have some sign,” he points out. “We don’t know the reason. Maybe they’re chronically inflamed and they’ve reached a point at which they have less sensation on the ocular surface. In any case, it’s not uncommon to have a discordance between signs and symptoms, and that’s been one of the big problems getting treatments approved for dry eye. The FDA in the past has required that a drug be effective in reduction of both symptoms and signs. But here we have a disease where the symptoms and signs rarely ever correlate well. How can we expect a treatment to fix both, when they don’t correlate to begin with? In fact, the drier you get, the more variation there is in all of these tests. So it’s not surprising that we haven’t seen many dry-eye treatment approvals.”

“Even after years of doing research in this area, I still don’t really know how much of dry-eye disease is directly attributable to meibomian gland dysfunction,” notes Dr. Pflugfelder. “There’s no question that many people with an unstable tear film but normal tear production volume have evidence of meibomian gland disease. At the same time, a lot of people have meibomian gland disease without manifesting any symptoms.

“It may be a disease that requires two problems in order to be clinically manifest,” he says. “For example, it may require some age-related changes on the ocular surface or in the tear film. Maybe decreased capacity for reflex tearing causes the disease to become more obvious to the doctor and patient. I think it’s still an area that’s evolving.”

Mysteries to Solve

For now, we seem to have more questions regarding meibomian gland disease than answers. “When it comes to meibomian gland dysfunction, there are still many things we don’t know enough about,” she says. “Why is MGD symptomatic in some patients but not others? Which patients do we need to treat? What’s the best way to treat? Hopefully, the workshop report will inspire much more interest in this disease, leading to new studies and data that will answer some of these key questions.”

“To have success treating meibomian gland disease, we may need to identify patients at an early stage when the glands are still salvageable,” notes Dr. Pflugfelder. “But that would require better diagnostic methods; either imaging or molecular markers of lipid function, something that would be simple for doctors to use. There are researchers who are looking at lipid profiles from normal and diseased glands and trying to make sense of it, and they are seeing differences in the lipids. Maybe what they learn will eventually filter down to the clinician. But right now you’d have to have a degree in biochemistry to really understand it.”

In the final analysis, when it comes to diagnosis Dr. Asbell notes that it’s not a yes or no situation regarding whether an ocular surface problem is being caused by meibomian gland disease or aqueous deficiency. “Many patients look like they have a combination of problems,” she says. “In fact, it’s possible that there’s a sort of crossover between multiple problems. Abnormality in the meibum could affect the tear film and tear production; you could end up with both aqueous deficiency and MGD, with both of them contributing to abnormality of the tear film and ocular surface symptoms.”

Dr. Pepose agrees that our understanding of dry eye is evolving, and notes that doctors are starting to focus more on an etiological assessment. “We’re trying to determine at the outset whether a patient really does have dry eye, with increasing help from objective testing,” he says. “I’m a proponent of that. However, it’s important to remember that even the best objective test isn’t a substitute for examining the patient. Doctors looking for diabetes can’t use blood sugar levels alone; they have to ask whether the patient has diabetic neuropathy or diabetic retinopathy. The same is true with dry eye. Testing factors such as osmolarity is important, but you still have to look at the lids. Is this more of an aqueous problem? Is it meibomian gland disease? Is it mixed? Then you can start appropriate treatment and monitor the results.” REVIEW

Drs. Asbell, Pflugfelder and Pepose have no financial ties to TearScience or any of the products discussed.