Common Encounters

“The most common type of ulcer clinicians are likely to see, by far, is a bacterial ulcer,” says John Sheppard, MD, MMSc, president of Virginia Eye Consultants, professor of ophthalmology, microbiology and molecular biology, director of residency research training and clinical director of the Thomas R. Lee Center for Ocular Pharmacology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Va. “Many of the organisms that cause bacterial ulcers have extremely potent tissue-destructive mechanisms, so it’s always imperative that bacterial keratitis is identified and treated rapidly. Pseudomonas, in particular, creates proteolytic enzymes like collagenase that rapidly degrade tissues; it’s known for creating ulcers that lead to perforations.

“The number one risk factor for corneal ulcers in the United States is contact lens use,” he continues. “Another key risk factor is trauma. Corneal ulcers are more common among those in industrial or outdoor occupations, and being older increases your risk—particularly in the case of a very old patient who has chronic blepharitis. Diabetics are at greater risk, as are patients suffering from dry eye. Latitude is important; the warmer the climate the more likely you are to develop an ulcer, and the more likely you are to develop a fungal ulcer. In Virginia we see more fungus than in Boston; in Florida they see more than we do.”

“Another ulcer that clinicians often run into is the peripheral corneal ulcer,” says John R. Wittpenn, Jr., MD, partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island and associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. “This isn’t so much an ulcer as it is a type of keratitis, an inflammatory problem associated with staphylococcus overgrowth in the lid. These individuals present with the classic peripheral infiltrate.

“If there’s a defect, I recommend treating it as an infectious ulcer until proven otherwise,” he continues. “But if the epithelium is fully intact and there’s no reaction in the anterior chamber, that’s phlyctenular keratitis, an inflammatory problem. You should address the lids with something like AzaSite, which has great penetration, or a topical ointment applied to the lid margins at bedtime in conjunction with an anti-inflammatory. I happen to like loteprednol because it’s a very good surface anti-inflammatory with a very low risk of pressure elevation. But you could also use a fluorometholone or something similar.”

Of course, the difficulty of treatment and likelihood of a positive outcome are profoundly affected by how quickly the corneal ulcer is detected and treated. “When a patient comes in early, even with a virulent organism, if the infection is limited to the anterior-most part of the cornea and the patient is treated intensively with appropriate topical antibiotics, he might end up with complete resolution of the infection and just a small anterior corneal scar,” notes Thomas John, MD, clinical associate professor at Loyola University at Chicago. “However, if the patient has a compromised cornea and presents later with a large corneal ulcer, even in the best scenario that can potentially result in a large corneal scar.”

Dr. Sheppard points out that this issue can be exacerbated by contact lenses. “A contact lens may actually mitigate the initial symptoms of an ulcer,” he says. “As a result, the patient may leave the contact lens on to make it feel better, thereby delaying presentation to the ophthalmologist or optometrist.”

Identifying the Organism

Charles Stephen Foster, MD, FACS, FACR, clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, and founder and president of the Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institution in Cambridge, points out that when a patient presents with a corneal ulcer, a number of questions should be asked to determine the diagnosis and a reasonable first-line treatment.

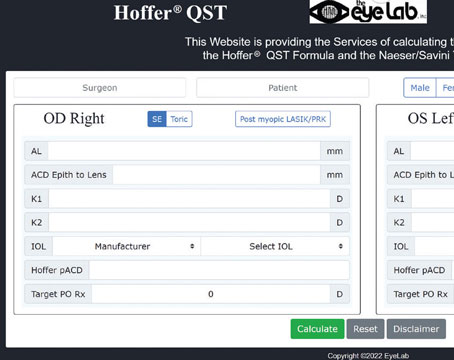

| ||||||

“In cases of microbial keratitis and stromal ulceration, in addition to culturing the organism, there are certain clinical cues and clues that can be helpful,” he continues. “These include obvious factors such as a discharge. If there is a discharge, what are its characteristics? Is it watery or more like pus? What color is it? If the discharge resembles pus, does it have an odor? Pseudomonas, for example, often has a characteristic sweet smell.

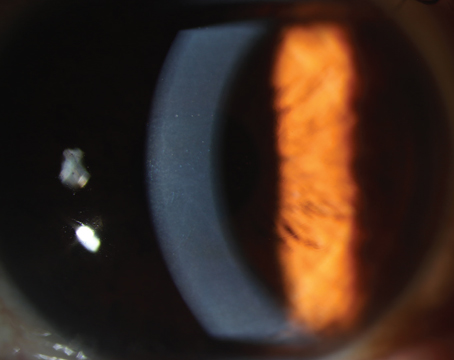

“With fungus there’s an infiltrate, and two or three other little white spots not connected to the infiltrate,” he notes. “You may see a bit of a plaque on the endothelium, on the inside behind the white infiltrate. It’s not always the case that a fungus is present when those signs exist, but the index of suspicion would be heightened if one saw those features.”

Dr. Foster adds that a herpetic ulcer is another, albeit less-common possibility. “If the patient has had herpes in the past, even if he comes in with something that doesn’t look like a classic dendritic epithelial defect, he may nonetheless have herpetic disease rather than a bacterial disease,” he says. “Simply testing corneal sensation at that point can often tell you a lot. If you find tremendously depressed sensation, that might indicate a neurotrophic ulcer. If it is a neurotrophic ulcer, pursuing the wrong course—hammering it with drugs rather than lubrication and maybe a bandage soft contact lens—is only going to make it worse.”

Taking a Culture

“I never empirically treat a true corneal ulcer or a serious-looking infiltrate without harvesting material for diagnosis,” says Dr. Foster. He notes that when culturing a microbial ulcer it’s important to include the edges and base of the ulcer, along with any discharge, for smears on glass slides and for plating onto various culture media. “I personally like two split plates, chocolate and blood agar,” he says. “You make streaks on each half of both plates; then, keep one at room temperature and put the other in an incubator. This is helpful because the one kept at room temperature will be extremely good for growth of fungi. I’ll also plate onto Sabroud’s medium for fungus, in addition to something for isolating anaerobic bacteria. Whether that is thioglycolate or another blood plate placed in an anaerobic incubator depends on my location at the time.

|

Dr. Sheppard adds that a culture can be taken from the conjunctiva and the cul-de-sac as well. “There’s a good chance that the organism growing in the cornea will be found in those locations,” he points out. “Also, with a contact lens user, you may be able to culture the infectious organism from the contact lens case, if the patient brings it in.”

Dr. Sheppard notes that there are visual and tactile clues that may suggest a particular type of organism when scraping a large ulcer. “With a gram positive organism, you don’t see too much tissue necrosis,” he says. “Instead, you get a kind of sandy consistency to the ulcerated corneal bed. On the other hand, a gram negative organism will produce a necrotic effect with loss of normal tissue and a lot of necrotic debris, a soupy appearance and mushy feel.”

Dr. Foster adds that you should never wait for the test results to begin treatment. “Starting treatment before knowing the results of the test is standard of care,” he says.

Dr. Foster notes that clinicians frequently ask whether they should do an anterior chamber tap for a culture when a patient has an ulcer and a hypopyon. “That’s a bad idea, because if the ulcer is bacterial, the hypopyon is always sterile, 100 percent of the time,” he explains. “Bacteria don’t get through an intact cornea. The hypopyon is a reaction, not an infection. But in the course of doing a tap, one may actually drag bacteria into the anterior chamber, inoculating it and risking creating a catastrophic endophthalmitis.

“The only instance in which I’d consider a tap is where we’ve never isolated the microbe; things are not going well—in fact they’re getting worse; there are some features that are making us pretty suspicious of fungus; and the process is getting deeper and deeper. I will do a tap in that situation, because fungus can pass through an intact Descemet’s membrane.”

Choosing an Antibiotic

“In ulcer cases where I’m really concerned, I want to use a potent broad-spectrum antibiotic in the fluoroquinolone class,” says Dr. Sheppard. “I think the best fluoroquinolone for ulcers right now is besifloxacin, because of its high concentration, its ability to adhere to the surface and its superior MIC values for a wide variety of infectious bacterial organisms, particularly multi-drug resistant staphylococci.”

Dr. Wittpenn’s preferred drug for corneal ulcers at the moment is also besifloxacin. “It has very good coverage from a fluoroquinolone standpoint—it covers both gram positives and gram negatives—and it contains benzalkonium chloride,” he explains. “Certain fluoroquinolones like besifloxacin or gatifloxacin, in combination with BAK, remain very effective against methicillin-resistant bacteria such as MRSA, which we’re increasingly worried about.

“If a patient comes in with any kind of ulcer that involves an epithelial defect, I prescribe besifloxacin every hour for the first day,” he says. “If you can’t get besifloxacin, my second choice would be a fluoroquinolone with BAK such as Zymaxid. If the patient’s insurance is generic only, which a lot of plans out there are, the third choice would be ofloxacin, again because it has BAK mixed in. It’s not as good as the other two, but may serve if the other options are not possible.”

If an ulcer is advanced, most surgeons say they’d treat with multiple antibiotics. “When treating a microbial ulcer, a typical treatment is to choose two antibiotic agents and treat aggressively,” says Dr. Foster. “By aggressively I mean perhaps six or eight initial drops, one every five minutes, followed by a drop of one of the antibiotics every hour on the hour with a drop of the other antibiotic every hour on the half hour.”

Dr. Sheppard concurs. “In more severe cases, I’ll use dual therapy with besifloxacin and gentamicin,” he says. “Gentamicin is not very soluble, so while the besifloxacin achieves very high concentrations initially, it takes a while for the gentamicin to build up. However, gentamicin is available in injectable vials, so when the patient is in the office I’ll give a subconjunctival loading dose injection of 0.3 cc gentamicin mixed with 0.3 cc lidocaine at the time of presentation, along with a drop of besifloxacin. (We don’t need to give this fluoroquinolone every five minutes to load the patient because of its superior pharmacokinetics.) That way I know the patient is immediately under treatment. Hopefully, the patient will go to the pharmacy right away and pick up the respective drops and then return to the office in that first critical 24-hour period, so I can see if he’s getting better.”

|

Dr. John points out that whether or not the epithelium is compromised makes a difference with regard to topical antibiotic penetration into the corneal stroma. “If the epithelium is intact, topical antibiotics have a hard time getting into the cornea,” he says. On the other hand, if the ulceration has already removed a piece of the epithelium and part of the stroma, you don’t have to worry about the epithelial barrier.”

He adds that when the epithelium is intact, the longer an antibiotic stays on the ocular surface the more likely it is to penetrate into the cornea. “Some drugs include an additional component that helps retain the drug on the ocular surface longer, leading to increased contact time,” he says. “For example, Besivance contains Dura-Site—polycarbophil, edetate disodium dihydrate and sodium chloride.”

The Steroid Dilemma

One of the most controversial issues surrounding treatment of corneal ulcers is when—and whether—to treat with corticosteroids.

“Corticosteroids are a double-edged sword,” says Dr. John. “Once the infection is controlled, steroids can help decrease the scarring that can result from the infectious process. However, when there’s an active infection you don’t want to use steroids because they’ll frequently have a deleterious effect. But that is often a million-dollar question: How can you be certain the cornea is sterile?

“The SCUT study (Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial), a large series involving 500 patients that was published in the Archives of Ophthalmology, found no overall difference in three-month BSCVA and no safety concerns with adjunctive corticosteroid therapy for bacterial corneal ulcers,” he continues. “But I usually avoid steroids when an infectious process is there. I would only use it when I believe the infection is completely under control, because you’re cutting down the cornea’s host defenses against the enemy and they can help the organisms proliferate.”

Dr. Sheppard agrees that corticosteroids can be useful, but only in specific circumstances. “I believe a classic gram positive infection will benefit from initial steroid therapy,” he says. “Recent data from the Proctor Foundation tells us that there may be an improved visual prognosis—but only for central ulcers when steroids are prescribed initially—and that the steroids have no significant unexpected deleterious effects [in this situation]. On the other hand, if the patient has a fungal infection, giving a steroid is the worst thing you can do. No patient with trauma should get a topical steroid because the risk of a fungal infection is much higher.”

Dr. Foster believes that if you’re sure a microbe is being effectively treated with the chosen antibiotic, a judicious use of steroid to reduce post-inflammatory response damage to the cornea is perfectly acceptable. “In this situation, where you have a significant level of comfort that you’re on top of this, if there is significant inflammation that you’d like to blunt, I believe most corneal disease experts would agree that stepping in with a little bit of steroid is reasonable,” he says. “I’m not saying it’s standard of care, but it’s reasonable.”

Dr. Wittpenn, however, feels that steroids are never a good choice when treating an infectious ulcer. “I find that steroids will get you in trouble faster than they’ll get you out of trouble,” he says. “The only time I’d use steroids is in a case like a phlyctenular keratitis, which is not infectious. Steroids have never been shown to decrease scarring. It’s tempting to use them because they’ll help the patient feel better, at least transiently, and the eye gets white faster. However, steroids can mask a lot of things.

“One patient was referred to me because she got a scratch working in the garden,” he continues. “She was treated by her local eye-care provider, who thought it might be bacterial and treated accordingly; however, it never got completely better. She still had some anterior chamber reaction, and the epithelium developed a funny appearance where it had partially healed. The doctor thought the trauma must have induced a herpetic keratitis, so he added an antiviral. But he still saw inflammation in the anterior chamber, so he also added a steroid.

“She was treated with the steroid and antiviral for about three weeks before she was finally referred to me because the ulcer wasn’t getting better,” he says. “By then she had started to develop a fungal ball in the deep stroma, and it ultimately broke through into the anterior chamber. At that point we did a tap of the anterior chamber and found that she had Aspergillus niger. It was difficult to treat. It took months, including 17 intracameral injections of an antifungal, amphotericin, which of course had to be specially prepared. She ultimately needed a transplant and cataract surgery. In the long run she did well—but the steroids certainly made the case much more difficult to treat.

“So I tell colleagues, if you’re dealing with what you believe is an infectious ulcer, you have to be very comfortable with what you’re doing before you add a steroid,” he concludes. “That’s probably the number one mistake I see clinicians make.”

Dr. John notes that you should also remember your treatment priorities. “Steroids may help to decrease scarring,” he says, “but if you have a bad corneal ulcer, the number one priority is to try to get rid of the offending organisms and minimize the overall direct and collateral damage to the cornea. In the best possible scenario, steroids might decrease the subsequent scar formation, but even if you use them you’re often not going to eliminate the scar.”

Fungal Ulcers

“Fungus is suggested as the cause of an ulcer when the history reveals that the ulcer is not becoming rapidly fulminant,” Dr. Wittpenn says. “It’s not developing a dense infiltrate quickly, and it’s not responding to antibiotics that are being used appropriately. Another clue that fungus may be involved is if the source of an abrasion was a scratch from vegetable matter such as branches or plants. At least up here on Long Island, the vast majority of fungal infections I take care of have that history; it may be a little different in the south where fungal infections are more common.”

“Fungal ulcers are often diagnosed late, because unless there’s an obvious cause we generally begin by assuming that patients have a bacterial keratitis,” notes Dr. Sheppard. “Fungal ulcers tend to be caused by trauma, but if the patient has a compromised surface, loves gardening, already had a corneal transplant or there’s a foreign body in the eye, all bets are off.

“You have to look at the physical appearance,” he adds. “A fungal ulcer tends to have very fuzzy margins, tends to be deeper and tends to present with a plaque on the endothelium; it may have a delayed onset, and may have multiple foci. These clues can help us decide where we rank the probability of a fungal cause for the ulcer.”

Dr. Wittpenn says he uses several approaches to address a fungal ulcer. “Suppose a patient comes in with what appears to be a bacterial ulcer,” he says. “It’s been treated properly, let’s say with tobramycin every two hours, but it’s not getting better or worse. The first thing I’d do is add a fortified vancomycin because the treatment so far hasn’t really covered gram positive bacteria that well; I’d also switch the patient to a fluoroquinolone.

|

Dr. John notes that even when the patient’s history gives you a high index of suspicion that the infection is fungal, you should treat for potential bacterial infection at the outset. “Treat with antibacterials and do the cultures to prove that it is fungal,” he says. “Antifungal treatments can often be toxic to the ocular surface. In this scenario you’re going to treat very intensively, so you want to have a definitive diagnosis before you start treating with those agents—although of course there can be some exceptions, depending on the clinical setting. Besides, even if fungus is present, you can also have a bacterial presence.”

He adds that it’s also important to know what kind of fungus you’re dealing with. “Is it Candida or is it a filamentous fungi like Fusarium? That also can help you decide what type of antifungal treatment to initiate,” he says. “You can change your treatment direction or add antifungal agents once you have a definitive diagnosis, either by smear, culture or biopsy.”

Monitoring Progress

“Once you start treatment with antibiotics, you have to monitor the corneal infection closely,” says Dr. John. “When you do cultures, you get a report identifying the organism and a report telling you whether the organism is sensitive to the antibiotic or resistant, but the single most important factor is the clinical response to treatment. If you’re treating a bad corneal ulcer and you see that the infiltrate size is getting smaller, the ulceration is not getting worse and there is evidence of healing taking place, especially in the periphery, then of course you want to continue with the same treatment modality. On the other hand, if you’re treating aggressively with an antibiotic and the ulcer is getting worse, you have to change direction or add additional antibiotics.”

Dr. John points out that bacterial organisms are very adaptable. “They become resistant to antibiotics,” he says. “It’s a constant battle to keep ahead of them. So you have to monitor very closely to see if your ocular antibiotic choices are working from a clinical standpoint.”

If medical treatment fails to work, surgery may become necessary. “You don’t want to wait too long for surgical intervention when there is an expanding ulcer with medical therapeutic failure,” notes Dr. John, adding that the clinical response is dependent partly upon the location of the ulcer. “For instance, if you have a Pseudomonas ulcer that is paracentral and is expanding rapidly despite medical treatment and moving towards the limbus, you may have to consider surgical intervention such as a therapeutic keratoplasty. If that infection spreads from the cornea to the sclera, resulting in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratoscleritis, then the odds of saving the eye as a whole can rapidly diminish. Even in cases where evisceration or enucleation are not necessary, the visual prognosis usually remains poor.”

On the other hand, if the treatment is working, the clinician has to decide when to taper the medications. “If the infiltrate is decreasing, the pain is decreasing, the redness is decreasing and the epithelial defect is improving, then I know that the patient is responding to therapy,” says Dr. Sheppard. “Once all of the symptoms are gone and the epithelium is completely resurfaced, I feel safe in concluding that we’ve eliminated the bacteria, and we can begin to rapidly wean the patient off the antimicrobial therapy. Sometimes, because of the toxicity that comes with any potent antibiotic given frequently, we cut back on the dosage frequency once we see improvement—assuming that the information from the cultures also indicated that the current therapeutic regimen is the right one. Finally, we watch the patient for about a week after we stop the antibiotics to make sure the cornea remains clear without therapy.”

Clinical Pearls

These strategies can help you avoid common mistakes that might undercut the effectiveness of your treatment:

• Don’t confuse an infiltrate with an ulcer. Dr. Foster notes that an infiltrate, by itself, is not synonymous with a corneal ulcer. “A corneal infiltrate indicates that some white blood cells have migrated into the corneal stroma, but that doesn’t mean an ulcer is present,” he explains. “In a true ulcer, there’s a loss of tissue with stroma digested by enzymes. The result is a divot, just like an ulcer in the lining of the stomach. An infiltrate is of concern because it can eventuate into loss of tissue—hence, an ulcer—but it’s important to make the distinction.

“If you have a peripheral infiltrate in a contact lens wearer, with no loss of stroma, no real ulceration and an intact epithelium, stop the contact lens use, use a topical combination of antibiotic and steroid and see the patient frequently,” he continues. “I’d see the patient the next day, and if he looks good, see him two days later, then four days later, and so forth.”

• Beware of undertreating a contact lens-related ulcer. “Sometimes a contact lens patient comes in so early that you don’t even see a big infiltrate,” notes Dr. Wittpenn. “I always warn people about a patient who says, ‘I think I scratched my eye when I took out my contact lens last night, because I woke up this morning and it was real sore and bothering me.’ All you see is a corneal defect—no infiltrate. In this situation you need to be alert for any cells in the anterior chamber and any kind of haze at all.

“My advice to most clinicians is: Any corneal defect in the setting of contact lens use is a corneal ulcer until proven otherwise,” he continues. “The biggest error clinicians make in this situation is prescribing an antibiotic twice or four times a day. When you hit the ulcer with a low dose like that—particularly if you’re using one of the very popular antibiotics like tobramycin or gentamicin—treatment might be effective, but those drugs have gaps in their coverage. Three days later the area still isn’t really healed in; it’s more inflamed, and now you’re not sure if you’re dealing with an unusual fungal ulcer or something else. Doctors end up sending these patients to me to rule out fungus, when in fact it’s an undertreated bacterial ulcer that just needs to be hit hard with topical antibiotics.

“A central contact-lens-associated ulcer can have devastating effects on vision, and develop very quickly, within 24 hours,” he adds. “That’s why any problem associated with a contact lens should be treated aggressively. If it really is nothing but a defect, nothing is lost. If it’s the start of an infection, you may save the patient’s vision.”

• When choosing an antibiotic, always consider avoiding those the patient may have used previously. “If the patient has had a particular antibiotic such as azithromycin or Ocuflox in the past because of cataract surgery or a bout of conjunctivitis, you may not want to treat the ulcer with those medications—particularly if the patient may have abused them by not using them for the full course of therapy,” observes Dr. Sheppard. “Instead, if the ulcer is serious, pick a very potent, broad-spectrum antibiotic, especially if you’re selecting monotherapy. If you’re using multiple drugs, select a strategy that will cover the broadest range of potential pathogens.”

• Be alert for a shield ulcer. “One form of ulcer that’s been a little more prevalent recently is a shield ulcer, which is associated with severe allergic conjunctivitis, commonly seen in teenage males, though it can also be seen in young adult males,” says Dr. Wittpenn. “They get such a severe allergic reaction and inflammation under their upper lids that the epithelium of the cornea breaks down in response to the inflammatory papillae that form, which become big bumps that can cause an ulcer. The real problem occurs if that ulcer becomes secondarily infected.

|

• Warn patients about secondary fungal infections. “Many times you treat a bacterial infection with antibiotics and the bacterial infection gets better,” says Dr. Sheppard. “Then the patient is running around in the garden or working in the basement or attic or playing with a pet and gets a fungus in the eye. Fungus will grow more rapidly in an eye with antibiotics on board, because suppressing the bacterial growth allows fungi to grow faster. As a result, we’ve often seen secondary fungal infections. It’s worth mentioning this to the patient.”

• Tell contact lens patients that they need to have a pair of spectacles in reserve. “Contact lens wearers often reject this idea,” notes Dr. Wittpenn. “They say, ‘I wear my lenses all the time.’ I tell them that they have to understand that if a contact lens starts to bother them, they have to be able to remove it and wear glasses until the problem is resolved. I’ve seen people get themselves in trouble because they had no spectacles to fall back on.”

• Be careful about diagnosing an infection as being herpes-based. “It’s possible to misdiagnose an infection as a herpes infection, leading to treatment using antiviral agents,” says Dr. John. “In fact, that early dendrite-like lesion that you see may be a radial keratoneuritis or an early epithelial ridge-like lesion secondary to Acanthamoeba keratitis. That misdiagnosis could delay the treatment of Acanthamoeba and have a deleterious effect on the patient’s vision.”

• Don’t be afraid to hospitalize a patient. “You have to consider the possibility that compliance is an issue, especially if the ulcer is getting worse in spite of your having prescribed what you think is the state-of-the-art treatment for the given problem,” says Dr. John. “Putting the patient in the hospital may be a good alternative if the patient is noncompliant, because time is of the essence, especially if you’re dealing with an organism like Pseudomonas. You can tell the patient that he won’t be in the hospital for too long; he’ll be discharged as soon as the ulcer begins to get better and he can manage the treatment at home.”

Dr. Foster agrees. “If the patient has a microbial ulceration that needs aggressive treatment, in my experience the vast majority of patients cannot be trusted to get it done,” he says. “By far the best solution is to let the nurses do it. Put the patient in the hospital. No insurance company would ever argue about hospitalizing a patient for an infectious corneal ulcer.” He adds that this is especially important if the ulcer is central or paracentral.

• Don’t assume that ongoing corneal opacity means your treatment isn’t working. Dr. John notes that clinicians may be fooled into overtreating by an ongoing corneal opacity. “A treated ulcer may be under control, but the clinician is concerned about the ongoing corneal opacity,” he explains. “This opacity may be the result of the scarring process rather than the infection, but the clinician keeps treating. This can lead to surface issues such as toxicity from the drugs and a corneal surface breakdown. The clinician should be tapering the medication because the infectious process is under control.

“Signs that your treatment is working despite the opacity include: healed corneal epithelium that was initially broken down; decreasing corneal stroma edema surrounding the area of initial dense infiltrate; and blurry infiltrate margins becoming more distinct,” he adds.

• Consider using cyanoacrylate glue to forestall a perforation. “A perforation is a pretty scary event,” notes Dr. Sheppard. “We may put cyanoacrylate glue on a cornea that’s thinning, and a small perforation can be glued. A large perforation, unfortunately, is going to require an emergency transplant.”

When Should You Refer?

“Any time you’re dealing with a type of ulcer you seldom treat, such as a shield ulcer, you should consider referring the patient,” says Dr. Wittpenn. “Generally, you have to be very comfortable discerning whether an ulcer is infectious or noninfectious. Also, any ulcer that isn’t doing what you expect it to do should be referred. Clinicians have a tendency to say, ‘Well this isn’t terrible, but it isn’t getting better. Maybe if I just give it a little steroid …’ Whenever you get the urge to reach for a steroid because you think it will help the eye heal faster, I urge you to resist. That’s the main choice that gets clinicians into trouble.”

“If you don’t actually enjoy managing these kinds of cases, don’t try to manage them,” adds Dr. Foster. “Just refer the case out to someone who does enjoy this type of case, or to the local residency program.” REVIEW

Dr. John is a consultant and speaker for Bausch + Lomb. Dr. Wittpenn has been on the speakers bureau at B+L and Allergan and has received research support from Allergan. Dr. Sheppard is a consultant for RPS, NiCox, Alcon, Merck, Allergan and B+L.