|

| Figure 3. FA of the left eye demonstrating multiple, pinpoint hyperfluorescent foci throughout the posterior pole. A similar appearance was seen in the right eye.

|

|

| Figure 4. The arteriovenous phase of the FA, left eye, with multiple, pinpoint hyperfluorescent foci throughout the posterior pole with subretinal leakage and pooling of dye. A similar appearance was seen in the right eye. |

The differential diagnosis for serous retinal detachments can be divided into vascular, inflammatory, neoplastic and congenital etiologies. Inflammatory causes include Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH), sympathetic ophthalmia, posterior scleritis and choroidal inflammatory diseases. Common vascular etiologies include malignant hypertension, toxemia of pregnancy, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, age-related macular degeneration and Coats’ disease. Neoplastic causes include choroidal melanoma, choroidal hemangiomas and choroidal metastatic lesions, while congenital lesions include optic nerve pits, colobomas and morning glory disk anomalies. Causes such as idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome, nanophthalmos and collagen vascular disease must be included in the differential diagnosis as well.

The patient’s blood pressure at presentation was 130/84. Laboratory testing included a complete blood count, Lyme antibody, angiotensin converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed, antinuclear antibody, chest x-ray and tuberculin skin test. Her B-scan did not show a T-sign or thickening of the sclera.

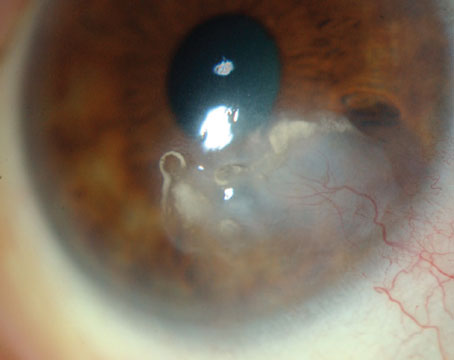

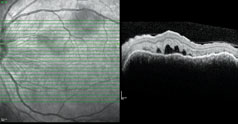

The patient was referred to the Wills Eye Institute Retina service, where she underwent additional testing. Her fluorescein angiography demonstrated early pinpoint areas of hyperfluorescence with a “starry sky” appearance (See Figures 3 and 4). Later phases showed leakage and pooling. The starry sky appearance on FA can be seen in numerous conditions, including: sympathetic ophthalmia; VKH; central serous chorioretinopathy; posterior scleritis; leukemia; disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; malignant hypertension; toxemia of pregnancy; hypotony maculopathy; uveal effusion syndrome; and lupus choroidopathy. The patient’s optical coherence tomography images confirmed the presence of large serous retinal detachments (See Figure 5).

Based on the patient’s age, race, prodromal symptoms, clinical findings of bilateral anterior uveitis, serous retinal detachments, small areas of retinal whitening and optic nerve hyperemia, it was felt that the patient was presenting with the first episode of acute-phase VKH disease.

The patient was started on 100 mg of oral prednisone daily in conjunction with ranitidine, calcium and vitamin D, as well as topical prednisolone and cycloplegic drops in both eyes. She was also referred to Rheumatology for initiation of steroid-sparing agents.

Over the next several months, the patient’s vision improved to 20/30 in both eyes. Her oral prednisone was tapered and her rheumatologist placed her on mycophenolate mofetil. The patient tapered and then discontinued her topical prednisolone drops. On exam, her serous retinal detachments and areas of retinal whitening resolved and only trace pigmentary changes remained.

Discussion

VKH is a bilateral, autoimmune, inflammatory disease with intraocular and frequently extraocular manifestations. It commonly affects pigmented races such as Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans and Middle Easterners. VKH rarely affects sub-Saharan Africans and is uncommon among Caucasians. It usually affects patients between the second and fourth decades of life. VKH is very rarely seen in children. It is more commonly seen in women, although this does not hold true in Japan.

In Japan, VKH accounts for 8 percent of all cases of uveitis. In China, this figure is greater than 15 percent. VKH is the most common uveitic entity in Saudi Arabia and is very common in Brazil, as well. However, VKH is much less frequently seen in the United States, with studies accounting for 1 to 4 percent of all cases of uveitis.

The differential diagnosis for VKH includes: sympathetic ophthalmia; primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma; Lyme disease; sarcoidosis; lupus choroidopathy; uveal effusion syndrome; posterior scleritis; acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (AMPPE); and multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS).

The etiology of VKH is still being studied, but it is believed to be an autoimmune T-cell mediated process against melanocytes. Patients with certain genetic variations are more at risk for VKH. Patients with the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele are most at risk, followed by HLA-DR4 and HLA DRw53. Certain viruses are suspected triggers of VKH. Specifically, the Epstein-Barr virus has been isolated from the vitreous in VKH patients.1

|

| Figure 5. Optical coherence tomography of the left eye showing marked subretinal fluid. A similar appearance was seen in the right eye. |

In the eye, one may see perilimbal vitiligo (Sigiura’s sign), subretinal lesions (Dalen Fuchs-like nodules), and a “sunset-glow” fundus. At this point, some patients never have repeat episodes. However, some patients will enter a chronic recurrent phase, in which anterior uveitis dominates. This phase can be associated with vision-threatening complications in more than 40 percent of patients, including posterior subcapsular cataract, glaucoma and choroidal neovascularization.2

Over the years different diagnostic criteria have been proposed, most recently in 2001 by Russell Read, MD, and colleagues.3 The new guidelines suggest three categories of disease: complete, incomplete and probable VKH. The guidelines state that to diagnose VKH, there must be a bilateral process with either early manifestations (e.g., serous retinal detachments) or late manifestations (e.g., sunset-glow fundus, Sigiura’s sign), no history of ocular trauma or surgery, and no clinical or laboratory evidence suggesting other entities. Furthermore, integumentary findings as well as neurological/auditory symptoms are useful in diagnosis and classification.3

Although VKH is a systemic disease, many patients present with only ocular findings. Recently, a large multicenter, multinational study of more than 1,100 patients with uveitis helped define the most specific diagnostic criteria for VKH. In patients with acute-phase VKH, 54 percent were found to have ocular signs only. In the chronic phase, 41 percent only had ocular manifestations. Specifically, among patients with bilateral, non-traumatic uveitis, the most specific findings for VKH are exudative retinal detachments in the acute phase (positive predictive value of 100, negative predictive value of 88.4), and the sunset-glow fundus in the chronic phase (positive predictive value of 94.5, negative predictive value of 89.2).4

Treatment of VKH depends on the severity of the disease, but the mainstay of treatment is corticosteroids. Studies have shown that high-dose oral corticosteroids used in the acute phase of VKH, followed by a slow taper over several months results in the best visual acuity. In addition, immunosuppressive agents may be employed for patients who are unresponsive, poorly responsive or intolerant of steroids. Both cytotoxic agents (e.g., azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil) as well as cytostatic agents (e.g., cyclosporine, FK506) can be used.

Numerous studies have looked at the visual prognosis for patients with VKH. Between 48 percent and 93 percent of patients will ultimately have a visual acuity of 20/40 or better. Factors indicating poor visual outcomes include increasing age at onset of inflammation, chronic inflammation requiring long-term corticosteroid treatment, and subretinal neovascular membranes.5

The author would like to thank Marc Spirn, MD, and Nikolas London, MD, Wills Eye Institute Retina Department, for their time and assistance.

1. Fang W, Yang P. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome: Mini Review. Curr Eye Res 2008;33:517-523.

2. Damico FM, Kiss S, Young L. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Seminars in Ophthalmology, 2005; 20:183-190.

3. Read R, Holland G, Rao N, Tabbara K, et al. Revised Diagnostic Criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: Report of an International Committee on Nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:647-652.

4. Rao NA, Gupta A, Dustin L, Chee SP, et al. Frequency of Distinguishing Clinical Features in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ophthalmology 2010;117:591-599.

5. Moorthy R, Inomata H, Rao N. Major Review: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. Surv of Ophthalmol 1995;39(4):265-292.