Caring for others can be stressful, as anyone who has cared for an aging family member can attest. So it shouldn’t be surprising that doctors often pay a price for being in their profession. In fact, statistical studies over the years have found that doctors—including ophthalmologists—are at higher-than-average risk of suicide, depression, drug abuse and divorce, among other things.1

Surgeons, notably, are at particular risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders—back pain, neck pain, numbness in the hands and arms, carpal tunnel syndrome, and so forth. Several survey studies have confirmed this:

- A 1994 survey of 325 ophthalmologists in the United Kingdom found that 54 percent of respondents had significant attacks of back pain, with those longest in the field having more frequent back pain.2

- In a 2005 survey of American ophthalmologists, 52 percent of the 697 respondents reported neck, upper body or lower back symptoms in the prior month, with 15 percent limiting their work as a result.3

- One hundred sixty-two respondents to a 2004 survey of ophthalmologists in Iran indicated that 80 percent suffered from chronic back pain and 55 percent had chronic headaches.4

- Data from a survey of vitreoretinal surgeons, reported at the 2004 meeting of the American Society of Retina Specialists by Uday R. Desai, MD, and colleagues found that among the more than 500 respondents, 55 percent reported both back and neck pain, and 7 percent required surgery. Only 15 percent reported experiencing no symptoms at all.

- Among 130 American ophthalmic plastic surgeons responding to a 2010 survey, 72.5 percent reported pain associated with operating; nine surgeons reported having to give up operating as a result.5

Increasingly, these disorders are being recognized as a cause of disability, productivity loss and early retirement. Although some of this could be attributed to the psychological stress of being a surgeon, much of the problem can be traced to specific physical strains associated with the profession. These include the stresses placed on the shoulders, neck, back, arms and hands as a result of less-than-ideal posture during exams and surgery, as well as repetitive actions common to the surgical profession. These issues—which are often overlooked by surgeons until their health is affected—can be addressed proactively.

Here, a number of individuals who have dealt with these problems, including surgeons who have suffered from musculoskeletal disorders and experts who help surgeons prevent and treat those disorders, share what they’ve learned about staying out of this kind of trouble—and undoing the damage if the problem has already occurred.

The Perils of Practice

| The AAO’s Task Force on Ergonomics |

|

In response to published reports and data from a recent American Academy of Ophthalmology membership survey, the AAO Board of Trustees has commissioned a task force on the ergonomic issues that affect clinicians and surgeons. The task force, headed by Jeffrey L. Marx, MD, chairman of the department of ophthalmology at the Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass., is composed of six ophthalmologists, along with a group of ergonomics specialists headed by Sandra Woolley, PhD, CPE, from the Mayo Clinic, and representatives from the AAO leadership.

“We have two primary goals,” says Dr. Marx. “First, we plan to inform academy members about common occupational musculoskeletal disorders and how to prevent them, via peer-reviewed publications, articles and presentations at meetings and special events, among other venues. Second, we’re developing ergonomic guidelines and standards for ophthalmic equipment, and we’ll encourage the device industry to adopt our suggestions.” The task force will be giving multiple presentations at the Academy’s annual meeting in Orlando, Fla., this month, as part of the Glaucoma and Cornea Subspecialty Day meetings and the AAO Young Ophthalmologist meeting. In addition, on Monday, October 24th, a presentation titled “Musculoskeletal Disorders in Ophthalmologists” will take place from 12:45 pm to 1:45 in room W309a. Topics addressed on Monday will include: the prevalence of MSDs in ophthalmology; ergonomic interventions in the clinic; ergonomic interventions in the operating room; and workplace exercises. —CK |

“According to the research literature, more than half of all ophthalmologists have experienced at least some signs or symptoms of an MSD—most commonly back pain, neck pain or pain in the shoulder, arm or hand,” she continues. “More that a third say they’ve changed their technique trying to avoid injury. I know that in other medical specialties these kinds of problems have resulted in significant numbers of individuals having to retire or eliminate activities such as surgery from their practice.”

Dr. Woolley says that the major risk factors ophthalmologists face are extreme or awkward postures; excessive force or exertion; and repetitive activities. “Excessive exertion is usually an issue when surgeons have to maintain a static position for the duration of a surgery, especially when their posture is awkward,” she says. “Often the surgeon’s head is in extension because of the microscope. If the arms are unsupported, that puts static force on the shoulders. In addition, ophthalmic surgeons tend to work with fine instruments, so the surgeon is exerting gripping forces on the instrument trying to keep it stable while working on the eye.” (She notes there may be additional exertion risks if the surgeon helps to lift the patient on or off of the surgical table.)

“Ophthalmologists are subject to a number of medical problems that are almost unique to our specialty, but most doctors are not aware of them,” agrees Robert M. Kershner, MD, MS, FACS, professor of anatomy, physiology and microbiology at Palm Beach State College, and president and CEO of Eye Laser Consulting in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. “Few surgeons are aware of their body position when they work, and as a result, few of us focus on keeping our backs straight and maintaining proper posture.

“Even if adjustments are made, such as getting extension tubes for the oculars so they can be placed level with the surgeon’s eyes and the head can be kept upright, we’re still locked into that position for many hours at a time,” he continues. “We’re not called upon to look laterally or move our head position, and as a result we can end up with a spasm of our contracted spinal musculature. This can lead to further problems down the road, such as degenerative disc disease in the neck or lower back. The neck can lose its mobility, which can translate into additional problems with our arms and hands.

“The bottom line is that it’s common to see retired physicians who complain of neck pain and muscle weakness in the arms and hands,” he says. “After years of doing surgery they’ve become a mess, and they probably never saw it coming. That’s one of the physical risks of being an ophthalmologist. After hours of surgery week after week, we’re just as subject to bodily injury as any athlete.”

Taking It in the Neck

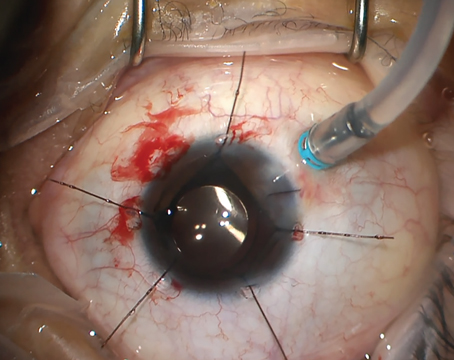

Neck pain is a common problem among ophthalmologists, and it’s not hard to see the connection to regular use of slit lamps and operating microscopes.

|

|

| At the slit lamp, many surgeons lean forward and crane their necks to reach the oculars—the “slit lamp slump.” (Top) Maintaining this position can result in neck and back pain and related nerve problems. |

As a cornea/anterior segment specialist, Dr. Baratz says he spends a lot of time at the slit lamp. “When you’re seated at the slit lamp, there’s a tendency to lean your body forward, flexing your back,” he explains. “When you flex your back, in order to keep your head straight, you have to extend your neck. That’s what I call ‘slit lamp slump’ (See images, p. 75). At the same time, the controls for the slit lamp are set relatively high, so you end up sitting like a praying mantis: Your lower back is bent, your neck is extended and your arms and wrists are flexed. This is a very unnatural posture, and it’s not good for your lower back, neck, arms or wrists. It’s much more natural to just sit up straight.”

Dr. Baratz says that one step he took to correct this was to purchase angled oculars. “They allow me to hold my head at a very slightly bent angle, which I find comfortable,” he says. “I also bought a more ergonomic chair that encourages me to sit more erect, with better posture.” Dr. Baratz notes that a number of companies display their ergonomic chairs at the annual meetings—an excellent opportunity for surgeons to try them out.

Arm Ergonomics

Another strategy Dr. Baratz employed was redesigning his slit lamp table, against which he rests his forearms during examinations. “These tables often have sharp edges that would bite into my wrists and forearms,” he says. “So I designed a table on which all the edges are smooth, so I can rest my forearms against the table comfortably. We also narrowed the table so I can bring my body closer to the slit lamp. That minimizes the need to crane my neck.”

Dr. Baratz says that the problem of slit lamp controls being positioned awkwardly will have to be solved by the manufacturers. “In many of the instruments we work with, the distance between our eyes and the hand controls is not quite right,” he says. “It’s more natural to have your hands a little higher than your belly button if you’re sitting upright, as we do when we’re typing. To use the slit lamp and many types of operating microscope you have to hold your hands at the level of your chest, bending your arm and flexing your wrist.”

Dr. Kershner notes that compensating for awkward posture at the slit lamp can also result in elbow injury. “When an ophthalmologist sits upright at the slit lamp, he tends to rest his elbow on something—usually the slit lamp table—to stabilize his hand, especially if he’s holding a lens,” he says. “Some ophthalmologists use a foam rest to cushion their elbow. Others let their elbow swing unsupported.

|

| Using your arms to compensate for awkward posture at the slit lamp (as illustrated above) can lead to elbow injury. |

“A key nerve that runs between these two bony structures in the elbow is the ulnar nerve,” he continues. “When you ‘hit your funny bone’ and feel an electrical shock that runs down to your fingers, that’s stimulation of the ulnar nerve. It provides sensation to the medial aspect of your hand and your fourth and fifth digits, and provides innervation to most of the muscles of the hand and some of the muscles of the forearm. When you bang your elbow onto something 100 times a day, day in and day out for 25 years, you start developing ulnar nerve damage and atrophy. The symptom is numbness, tingling and weakness in your hands. The muscles then weaken because of what is called an ulnar palsy.” Dr. Kershner says many ophthalmologists have this condition but are totally unaware of it. “It gets worse as you get older,’ he adds.

Using the Microscope

The head-forward posture that many surgeons adopt at the microscope also takes a toll over time. “If you go into a room at an ophthalmic meeting, look at the doctors sitting, walking and talking to one another,” says Dr. Kershner. “If you look closely, you can identify who the busy surgeons are. They have what’s known as a head-forward posture; the head looks like it’s pushed forward on the neck. The older the surgeon is, the more obvious it is. Some call it stoop-shouldered; it makes you look like you’re slumped over a little. That’s a consequence of long hours spent at a microscope. I see this in hand surgeons as well, because they also sit at a microscope all day operating on the nerves and tendons of the hand, adopting a similar body position.”

|

|

| Hours spent in poor posture at the surgical microscope (i.e., back arched, neck bent forward, as illustrated above) can eventually lead to chronic pain and movement restriction.

| |

“The angle between the oculars and the barrel of the surgical microscope—the part that points down toward the patient’s eye—used to be fixed,” he notes. “So surgeons, especially tall surgeons, often slumped over to use the microscope. By the end of surgery, they’d be saying, ‘I have the worst neck ache; the backs of my arms are numb. I’ve got tingling and nerve compression.’ The obvious solution is to sit up straight, but sometimes that’s not easy to arrange. If the surgeon is very tall and the assistant is short, for example, making the height ideal for the doctor might make the microscope unreachable for the assistant.

“The correct way to sit in the operating room is with a straight back, not leaning forward, and a straight neck, as if you were looking at the wall in front of you,” he continues. “Ideally, you should adjust your chair height to maintain that position and incline the oculars so you can see what you’re doing. You should have support for your back, but I’d advise not using armrests, at least for cataract or retinal surgery. The problem with armrests is that if the patient moves his head, your arms are trapped on the armrests and you can’t move with the patient. Many surgeons deal with this by taping the patient’s head down, but that’s potentially dangerous to the patient and doesn’t give you the flexibility to look at the peripheral retina during retinal surgery, or to get different angles, better views and a better red reflex during cataract surgery.”

Another way to avoid issues with bending over a microscope is to use one of the new television systems, with the surgeon looking at a screen using special 3-D glasses instead of through the microscope. “I have a TrueVision system,” says Dr. Charles. “It provides a good view, but it has altered stereo perception, and it doesn’t have quite the dynamic range that a straight optical view does. So far, I like it for teaching but I don’t use it for surgery.”

An Ergonomic Office

The way an ophthalmologist’s office is laid out can also have a significant impact on body strain. After Dr. Baratz underwent neck surgery to relieve his symptoms, he started thinking about the equipment he uses and how this kind of neck problem might be prevented. “I redesigned my office to make it ergonomically more acceptable,” he says.

“Where you sit in relation to the patient, the patient’s family and your workstation affects how you use your neck and arms,” he notes. “One of my exam rooms was set up so I’d examine the patient looking straight ahead. Although I’m right-handed, my computer was off to my left, so I was turning my body to the left to type on the computer. The other family member would be seated behind me to the right. So for me to interact with the patient and the patient’s family while I was typing on the computer, I was turning my neck almost 180 degrees. This layout would work perfectly for an owl!

|

|

|

How your office is laid out affects how much strain is involved in reaching for keyboards and instruments, as well as how far you have to turn your head to address the patient and family members. |

“The last thing I did was get all of my instruments and lenses as close to me as possible, so I wouldn’t have to twist and reach to retrieve them,” he says. “To accomplish this, I put my instrument table to the left of the patient chair and on wheels, so that it can be positioned close to me. I call the result a ‘cockpit’ design. As in a cockpit, everything is within reach; you don’t have to lean over or twist your body around to get something.”

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Robert Direnfeld has been a practicing physical therapist for 28 years, and has helped a number of microsurgeons deal with back, neck and arm problems. He explains that carpal tunnel syndrome is a compression of the median nerve—the nerve that feeds the palmar surface of your hand, as well as the thumb and first two fingers and half of your ring finger. “That nerve path goes right underneath the transverse ligament at your wrist,” he says. “The ligament goes from your thumb to your little finger, creating a kind of tunnel. Your median nerve passes under that ligament, through the tunnel. In carpal tunnel syndrome, the nerve becomes entrapped under the ligament, usually because that ligament has thickened over time as a result of repetitive use.

“That’s why, whenever you engage in a lot of repetitive motion, as most ophthalmologists do, you’re setting yourself up for a variety of different problems, including carpal tunnel syndrome,” he says. “Of course, it depends on how you’re sitting in your chair and using the microscope or slit lamp. For example, in the case of one surgeon I worked with, armrests were part of the solution. I wanted to take stress off his arms because he was using his hands repetitively, which predisposes you to this type of injury.”

Mr. Direnfeld notes, however, that other problems can mimic carpal tunnel. “The median nerve begins in the neck,” he explains. “Sometimes it’s hard to tell whether the symptom is being produced at the neck or the wrist, or both. I’ve seen patients who had carpal tunnel surgery and still ended up with numbness and tingling because the problem was actually at the neck. So, diagnosing the problem is important. If you suspect you have carpal tunnel, I’d see a physical therapist to be fully evaluated so the real source of the problem can be determined. If the problem really is carpal tunnel, we’d do one specific set of treatments and exercises; if the problem is coming from your neck, we’d do an entirely different treatment.”

How does a physical therapist treat carpal tunnel syndrome? “First, we look at what’s causing it,” says Mr. Direnfeld. “Most of the time the ligament has thickened, so we use different modalities: ultrasound; cortisone; some massaging; and some stretching of the tissues, to try and open up that space. We also focus on strengthening the related muscles. In many cases, if the carpal tunnel is severe, the nerve is getting pinched and the muscles supplied by that nerve start to atrophy. For a surgeon, that could be catastrophic. So we work to restrengthen those muscles, retraining them to work, trying to keep them flexible and strong.

“Of course, if the problem has gone on long enough that the ligament has become very thick, therapy may not help. At that point it’s become a mechanical problem. The tunnel is simply too narrow. That’s when you have to send the patient to the surgeon and have the tunnel opened up. Basically, the surgeon will remove the ligament, because you don’t need it in order to function. It’s not a complex surgery. But even if you pursue this route, working on strengthening the muscles will make their functional return a lot more rapid after the surgery.

“In any case, it makes sense to try physical therapy first,” he adds. “You have everything to gain and nothing to lose.”

Other Ways to Get in Trouble

Looking into the slit lamp or microscope and twisting to accommodate patients in the office are not the only ways ophthalmologists put undue stress on their bodies:

•

Leaning forward to talk to patients. Dr. Charles says he used to do this all the time. “It shows that you’re emotionally engaged with the patient,” he explains. “If you lean back when you’re talking to people, your body language suggests that you’re not engaged, not sensitive. So you lean forward—and then you go home and say, ‘Geez, I have a low backache and a neck ache.’ No kidding! You’ve been bending over all day to show you care.

|

| Ophthalmologists often lean forward when addressing a patient so that their body language conveys interest and concern. However, maintaining this posture can lead to back and neck pain. |

“To avoid this, I pull the slit lamp up and sit straight up without bending my neck to examine the patient,” he continues. “Then, I roll the slit lamp out of the way, and when I’m talking to the patient I walk around to the patient’s side. Unless the patient is female, I put my hand on the patient’s shoulder.”

|

|

| Using two foot pedals of different heights—or having one foot on and one foot off the pedals—can result in the surgeon leaning slightly to one side during surgery, adding to back strain. |

• Using the indirect ophthalmoscope. Dr. Charles notes that a key problem when using an indirect ophthalmoscope is the necessity of seeing into the patient’s eyes from different angles, which can result in the doctor twisting his neck and body into different positions. “If you have an examining chair in the office that has sort of a cup-shaped rest under the patient’s head, it limits the patient’s head rotation,” he says. “You’ll find yourself bending your neck all day long.”

His solution is to move the patient’s head instead. “Do as horse trainers do,” he suggests. “Supple the patient’s neck and gently move the patient’s forehead back and forth, side to side. Say things like, ‘Can you relax your neck a little bit? I’m trying to look at the side part of your eye with the scope …’ If you can rotate the patient’s head enough to see both sides of the eye, that eliminates the need to put huge stresses on your cervical spine with a heavy indirect ophthalmoscope on your head.”

Dr. Charles notes that the weight of the ophthalmoscope is always an issue, but this has improved in recent years. “The ideal weight for an indirect ophthalmoscope is zero,” he observes. “That’s not achievable, but modern materials and better design have made them lighter, and the manufacturers are well aware of the problem. I actually wear a spectacle in-direct with my correction built in. It provides a better view, and it doesn’t have a head strap.”

• Compensating for inadequate leg room. Dr. Woolley notes that depending on the surgical bed that’s being used, the physician’s leg that’s closest to the surgical bed may be butting up against the bed frame. “To compensate, the surgeon may twist his or her leg a little bit so that it fits underneath the bed,” she points out. ”That’s not a good thing.”

• Using body language. A problem like carpal tunnel may not always produce the symptoms you’d expect, or appear because of the kind of repetitive motions most people associate with the condition.

“About 12 years ago I started feeling a sharp pain in my right shoulder,” says Marguerite McDonald, MD, FACS, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU Langone Medical Center in Manhattan and a cornea/refractive/anterior segment specialist with Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island in Lynbrook, N.Y. “It was awful; it kept me up at night. If it had been my left shoulder, I would have thought it was a heart attack. Eventually I went to a neurologist, who did several invasive, painful tests. He told me I had severe carpal tunnel syndrome.

“That didn’t make sense to me,” she continues. “I’m left-handed, and the pain was in my right arm. Besides that, the pain was in my shoulder, not my wrist. The neurologist agreed that it was an atypical presentation, but noted that carpal tunnel can give patients shoulder pain without any other symptoms. He showed me the tests, and they were unequivocal. He said, ‘You have to find out what you’re doing over and over with your non-dominant hand that could cause carpal tunnel syndrome.’ As far as I knew, I didn’t use my right hand much at all.

“I had carpal tunnel surgery which went well, and I was back operating three days later,” she says. “But I still wasn’t sure what had caused the problem. Finally, I figured it out: When I was in an exam lane and wanted to signal to a patient that time was up—i.e., ‘I have to leave, please wrap it up and ask your final questions’—I’d get up and lean on my right arm with all of my weight while I wrote out the last little bit of my chart note. My body language worked like a charm—patients would get the message, ask their last question or two and the visit was over. I’d been doing this for years, putting my body weight on my non-dominant hand as a signal that I was about to leave the room. That was what caused my carpal tunnel syndrome.”

Dr. McDonald notes that most people who develop carpal tunnel do so for more predictable reasons, such as repetitive motions during surgery or from long hours on the computer. “But we often do repetitive things we’re not aware of,” she says. “There are all kinds of orthopedic and neurological injuries you can get being an ophthalmologist.”

Getting Help: Diagnosing the Problem

Once symptoms appear, where should a surgeon turn for help? Many surgeons have avoided surgery by seeing a physical therapist.

“After finishing a day of surgery I’d get into my car and discover that I couldn’t turn my head to back out of my parking space,” says Dr. Kershner. “That’s when I knew I had a problem. I sought out the opinion of a neurosurgeon and an orthopedist. But they weren’t familiar with the issues unique to ophthalmology; they didn’t know about the physical risks of our job.

“Luckily, I went to see a physical therapist who had a better picture of what was causing my problem because he’d worked with other microsurgeons,” he continues. “He knew exactly what to do. He followed me into the OR and watched me operate. Then, he advised me to switch to forearm rests on a surgical stool, rather than arms on a chair or worse yet, a wrist rest. He showed me how to properly position myself at the microscope, paying strict attention to the posture of my neck and back. He gave me a series of exercises to strengthen key muscles and stretch the ones that went into spasm. He showed me how to release a muscle spasm after surgery, where and when to apply ice and when to use heat, and how to use massage to prevent repetitive stress injury. Working with him changed my life, both in and out of the OR.”

Physical therapist Direnfeld says the first warning sign of trouble is usually pain, either during or after the problematic activity. “The doctor will have soreness in whatever area he’s stressing,” he explains. “The second obvious sign is that he may begin to notice some lack of mobility or range of motion. Depending on the area involved, he may find that he can’t turn his head as far as he needs to, either in the operating room or outside.”

When an ophthalmologist notices this kind of symptom, Mr. Direnfeld suggests seeing a physical therapist for evaluation. “The trick is figuring out exactly what’s going on,” he says. “In most cases it’s a structural problem, such as tight muscles, tight joints or postural weakness. These are the kind of issues a physical therapist specializes in addressing.

“However,” he continues, “you also want to make sure you’re not dealing with a tumor or something that’s coming on slowly and mimicking a muscle or joint problem. One of my pet peeves is when a doctor prescribes exercises in this situation without evaluating the problem, or when people treat themselves by looking on the Internet for neck exercises. You should be evaluated either by a physician or by a licensed physical therapist to see what’s going on. If it’s clear that the problem is one that can be addressed by physical therapy, we can develop a program to treat it.”

Mr. Direnfeld notes that he’s not an expert in problems specific to surgery; his therapeutic strategies in these cases resulted from seeing the surgeon working in the OR. “I scrubbed and was present in the operating room as an observer,” he explains. “For example, I watched one of the surgeons performing multiple cataract surgeries. In addition to the postural problems, I could see that he wasn’t moving his arms a lot; the surgery seemed to primarily involve hand and wrist movement. So for this type of surgery, having something to rest his forearms on took a lot of strain off of his neck. Obviously, the type of movement the surgeon makes will depend on the kind of surgery he’s doing. An orthopedic surgeon doing knee replacement has to move his arms around a lot, so in his situation, armrests wouldn’t be practical.”

Treating the Problem

To help these ophthalmologists, Mr. Direnfeld says two things had to be accomplished.

“First, we had to address the physical problems that had been caused by the surgeons working in that position for so long—primarily tightness in their upper cervical segments—by having them do an exercise program designed to keep them loose,” he says. “Second, we had to find a way to prevent the problem from recurring.”

|

|

|

| Physical therapists may prescribe exercises to stretch muscles in spasm and retrain posture. Above left and center: an exercise called a chin tuck. From a neutral starting position (left) the patient slides the head backward as if it were on a rail, pulling the chin into the face and creating a “double chin.” The position is held for five seconds before relaxing. Typically this is repeated 10 times in a row, two or three times a day. Above right: A general neck/upper quarter stretch. One arm is placed behind the back, while the head is turned and tilted down, as if trying to put the chin in the opposite armpit. The other arm reaches behind the head and gently pulls in the same direction. This position is held for five seconds before relaxing. If prescribed, the exercise is typically repeated 10 times in row, twice a day. Both exercises help to maintain mobility and offset the prolonged abnormal postures that can accompany performing ocular surgery.

| ||

One strategy physical therapists often use to relieve this type of posture-related strain is strengthening the abdominal muscles—i.e., increasing core stability. “One of the surgeons had some lower back trouble, just because he’d been compensating for his neck pain for so long,” says Mr. Direnfeld. “So it was important to increase his core stability. Again, if your lower back and your abdominal muscles are strong, that’s going to hold your entire spinal system intact and keep it stable, taking pressure off of other areas. That’s why we always work on core stabilization if a person has any kind of back issues, or related knee or shoulder problems.

“The most important thing we did to prevent the problem from recurring was convince the hospital to buy ocular extensions for the microscope,” he continues. “The extensions were expensive, and the powers that be at the hospital didn’t want to buy them. Finally, one of the surgeons threatened to take his patients to another hospital that would buy the extensions, and the hospital agreed. Both surgeons work at this hospital, so they both benefited from this change.”

Mr. Direnfeld notes that one of the doctors purchased a more ergonomic chair as well. “The new chair is more like an office chair but with good arms, and it can be raised up high, almost like a bar stool, so he can get high enough to work without bending over. The armrests helped to take the stress off of his neck and shoulders.”

Mr. Direnfeld points out that treatment should be individualized. “I’d prescribe different solutions and exercises, depending on what the problem is,” he says. “The exercises should be based on where your restrictions are, or where your weakness is. A good physical therapist will design a program specific to you and your problems.”

The Surgical Option

Often, the first thing surgeons think of when they develop back trouble is back surgery. John S. Jarstad, MD, medical director of Evergreen Eye Centers and an adjunct professor at Pacific Northwest University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Yakima, Wash., says that about 10 years into his practice he began having back pain and weakness. “It turned out that I had a herniated disc,” he says. “I tried to put up with it, but finally I couldn’t sleep; I was lucky to get two hours a night. The only way I could get relief was to pace back and forth in the hallway at my house. So I finally went to see a doctor. He told me the disc couldn’t be treated medically; it needed surgery.

“Luckily, microdiscectomy these days is far easier than back surgery a few decades ago,” he continues. “It’s like the difference between small-incision cataract surgery and extracapsular cataract surgery. Traditional disc surgery involves making a pretty long incision—maybe three inches—to remove the disc and fuse the vertebrae. Rehab would take about three months. In my case, they just took out the herniated part of the disc through a half-inch incision, and I was back to work in a week. (I didn’t believe it was possible, but it was.) They also have materials nowadays that can be used to replace an unrepairable disc. So if you have a herniated disc and you’re a candidate for microdiscectomy, I think the surgery is worth considering.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Direnfeld suggests that surgery should be thought of as the last resort. “Cutting is always an alternative, but any good surgeon, no matter what your problem, will tell you that you should try everything else before you resort to it,” he says. “A lot of problems involving pain and restricted movements can be resolved by physical therapy. That even includes herniated cervical discs, although these are rare among ophthalmologists, because the job doesn’t predispose them to it.”

Mr. Direnfeld notes that the surgeons to whom he sometimes refers patients won’t even consider surgery unless the patient has tried physical therapy first. “Occasionally I work with a patient who doesn’t improve,” he says. “If I send that patient to a surgeon, I have to make sure I include a note saying that we’ve already tried therapy. If he doesn’t see that note, he’ll just send the patient back to me for therapy.”

Making Your Tools Work for You

A big part of avoiding trouble comes down to making sure your instruments and office layout minimize the strain on your body. Helpful strategies include:

• Purchase movable oculars for the surgical microscope. “Eyepieces that can move in and out and up and down should help the surgeon avoid assuming an awkward neck position,” says Dr. Woolley.

• At the slit lamp, raise the patient’s chair. “The biggest problem I encounter is hunching over at the slit lamp to examine patients, and twisting to move the slit lamp back and forth,” says Dr. Jarstad. “By raising the patient’s chair up to eye level I can sit fully erect. I’ve caught myself hunching over with my neck extended and my back flexed many times, and I know that’s contributed to my back problems.”

|

| Stools such as the Salli saddle chair are designed to balance the pelvis in an upright position, supported by the ischial bones. This improves back posture. Stools are available with movable elbow tables and/or adjustable backrests. (For more information, visit salli.com.) |

“In general, you want your back and arms to be supported,” she continues, noting that back support can be provided by having a backrest with lumbar support on the chair, or by a style of seat that forces the back into a better posture, such as a straddle stool (See photo, right).

“You want your feet flat on the ground or on a footrest. Having a full-length back on the chair is probably more important if you’re going to be sitting in the chair for a long period of time, but lumbar support is valuable in any chair or stool.” She adds that having adequate support for the arms can not only reduce stress on the neck and shoulders, but may also reduce strain on the back and help the surgeon steady his or her hands.

Regarding stools, Dr. Woolley notes that having back support is generally a good idea, although straddle stools are becoming more popular for use in the OR. “These can work well in a surgical situation,” she says. “The seat resembles a horse’s saddle; it forces the sitting person into lumbar lordosis, i.e., the proper curvature, because the seat is tilted forward. Because of the tilt in the seat, the surgeon is sitting, but almost standing, too. It’s surprisingly comfortable, even though it may not appear that way. Some of these are available with a movable backrest that can be rotated around to serve as an armrest. Many physicians now use these in the OR.”

• Try thicker padding under your office carpet. Once he realized he needed to minimize the stress his back was being subjected to, Dr. Jarstad says he made sure the floor he stood on all day wasn’t rock hard. “When we redesigned our office, instead of a standard carpet pad, we elected to go with the thickest carpet pad we could find—I believe it was 5/8 inch thick,” he says. “It’s definitely easier on your back.”

• Give serious thought to your exam room layout. Dr. Woolley is currently involved in a project designed to maximize the user-friendliness of exam rooms. “We’re trying to provide as much adjustability as possible,” she says. “For example, we’re putting our monitors on arms so they can easy be moved to allow the patient to see the screen. We’re asking doctors and technicians, ‘What do you need in this room? What don’t you like in the current setup?’ We’re trying different arrangements to see what works best. How does the traffic flow work? Where should the sink be? The sharps box? The final result should allow our doctors and technicians to be more effective with less physical strain.”

• Arrange exam rooms consistently. “This ensures that if the physician has to move from room to room he won’t waste time and effort because he’s not sure where something is located,” says Dr. Woolley.

• Encourage manufacturers to develop instruments and tools that take ergonomic needs into account. “For example,” says Dr. Woolley, “low-profile foot pedals that are almost flat do exist. If surgeons ask for this, or for surgical tools that are easier to grip for long periods of time, or oculars that are adjustable, manufacturers will eventually incorporate these features into their products.”

Take Care of Your Body

The other half of the equation in avoiding MSDs is paying attention to the signals your body is sending you and making sure you meet its needs. To do that:

• Avoid maintaining one position for extended periods. “During the day, try to vary what you do as much as possible,” advises Dr. Woolley. “Don’t do 20 cataracts in a row if you can alternate with something else in which the positioning isn’t too similar. Take regular stretch breaks between cases; do stretching exercises for the various joints you’re straining—your back, your neck, your shoulders and your arms. As much as possible, alternate between sitting and standing.”

• Choose your shoes to lessen your stress. Dr. Jarstad suggests using gel insoles in your shoes to reduce impact. “Additionally, you can buy shoes that have a coil spring built into the heel,” he notes. “I use a brand called Gravitydefyer; you can get ones that look like dress shoes, as well as ones that look like running shoes. They offer a lot of shock absorption when you’re walking. I’ve used those for the past five years and haven’t had the back problems I had in the past.” (To learn more about these shoes, visit

gravitydefyer.com.)

• Rest by standing or lying down—not by sitting. Although it may be obvious that the stress on your back is lowest when you’re lying down flat, few people realize that the stress and compression forces on your discs are considerably less when you’re standing than when you’re sitting. “Sitting puts 250 times as much pressure on the your discs as lying down does,” Mr. Direnfeld notes. “Standing only creates 100 times as much pressure.

Dr. Jarstad says learning about this has changed his after-work routine. “In the old days when I got home from work, my first thought was to sit down to read the paper or eat dinner,” he says. “Now when I get home I either swim, lie flat or go walking.”

• Focus on maintaining a good atmosphere in the OR. “I do whatever it takes to maintain my emotional wellbeing in the OR, so it doesn’t become a stressful, dark world,” says Dr. Charles. “I sit so I’m comfortable; I try to be a little Zen about relaxing. For example, I leave the shades up in the OR so I can see the sky. I pay attention when something doesn’t feel right or I’m a little nervous. I make changes until the problem is fixed.”

• Treat your shoes like one of your tools. “Your feet are like the foundation of your house,” says Dr. Woolley. “If they’re having a problem, you want to address it so your entire house doesn’t start to crack. A misalignment in your feet will affect your knees, your hips and your back. So make sure you wear good shoes, with orthotics in them if you need them. You can go to a podiatrist, someone in foot orthopedics, a sports medicine specialist or a physical therapist to get advice on this.”

Dr. Woolley adds that it’s important to not wear the same pair of shoes day after day. “Our feet perspire, and shoes break down over time,” she notes. “I usually advise wearing a different pair of shoes Monday, Wednesday and Friday than you do on Tuesday and Thursday. Give the shoes a chance to dry out between wearings, and they’ll last a lot longer.”

• Consider using a back brace to keep your back straight when you’re working. If advised by a specialist, this might be a helpful preventative. “The brace can have metal supports along the spine and sides to keep you from bending too much,” says Dr. Jarstad. “I’ve used those in the past, during surgery in particular, and that’s been helpful.”

• If you develop symptoms, don’t wait until the problem is disabling to get help. “If you have an ache or discomfort that continues after you’re done performing an activity,” says Dr. Woolley, “seek medical advice before the problem gets more serious.”

• Try a licensed physical therapist first. “As ophthalmologists, we want the quick fix,” notes Dr. Jarstad. “We do that for many of our patients, but backs are a little different.

“Physical therapy helped me deal with my back problems,” he continues. “I think it’s a good idea to see a physical therapist if you start to have back pain and it lasts longer than a week. At first I didn’t know much about physical therapy, and I didn’t have a whole lot of confidence in it, but it helped tremendously. I suspect that the majority of people wouldn’t need back surgery if they could get physical therapy and change their habits a little bit.”

• Consider having your therapist observe you performing the work that’s associated with your symptoms. “The first ophthalmologist I worked with had already tried to address his symptoms by changing his chairs, changing his position at the operating table, and so forth,” says Mr. Direnfeld. “But once I observed him performing surgery, it was immediately clear what was causing the symptoms.

“I think letting a physical therapist observe you at work is a good strategy, especially if the symptoms are occurring when you’re engaged in a specific activity,” he concludes. “Sometimes you need a person who’s trained in this area, another set of eyes to help figure out exactly what’s wrong.”

Ergonomics expert Dr. Woolley also used this strategy before offering advice. “I was approached by ophthalmologists here at the Mayo Clinic,” she says. “A number of surgeons were experiencing pain and discomfort, and they asked me to take a look at what they were doing. In order to advise them, I videotaped them at work in the operating room and clinic.”

• If you exercise, choose a low-stress workout. Dr. Jarstad notes that non-ophthalmic activities can also contribute to skeletal problems. “I used to be a long-distance runner,” he says. “For many years I pounded the pavement running on concrete or asphalt, which can be very hard on your back. Since my back surgery I’ve switched to lower-impact sports and aerobics; I use the elliptical at the gym and go swimming or bicycling.”

• If needed, give your neck extra support at home. Dr. Jarstad says he sometimes has worn a soft neck collar after work to relieve minor symptoms. “I used this strategy one weekend when I started to get the same symptoms in my neck as I’d already had in my back,” he says. “I put a neck collar on and got immediate relief. I used it when I got home from work for about a week, and my neck returned to normal.” He adds that some of the specially designed memory-foam neck pillows can help to avoid worsening neck strain overnight.

• Consider seeing a sports doctor. “We’re in a very physical profession,” notes Dr. Jarstad. “We make the finest detailed movements that a human can perform. In that respect, we’re like high-performance athletes. I’ve found it very helpful to work with a sports doctor, because they deal with all kinds of physical strains and injuries; you just have to explain the kinds of stresses your body is being subjected to. And of course, they can also give you good advice if you engage in any exercise programs or participate in sports.”

• Be aware that the problem could get worse. “I won’t be surprised if we start seeing a rash of neck and carpal tunnel-type syndromes among all doctors, as everyone moves to electronic medical records,” says Mr. Direnfeld. “All the doctors who used to sit at their desks with a chart are now switching to using laptops or computers, so they sit and type all day.

“Even iPads can be problematic,” he adds. “At least when you’re sitting at a desk with a keyboard you can get yourself into a fairly good position and maintain it. With the iPads, you tend to be balancing it with one hand while you’re trying to work, so you’re not maintaining your posture as well as you should. I think we’ll see more symptoms in every area of medicine as doctors and staff use these more.”

Physician, Heal Thyself

Ironically, surgeons are sometimes better at caring for others than themselves. “Ophthalmologists are professionals at restoring sight, but they are not professionals at taking care of themselves,” notes Dr. Kershner. “Doctors often take better care of their cars than they do of themselves. The irony is, you can buy a new car, but you can’t buy a new body.”

Dr. Charles agrees that making the effort to preserve your own health and well-being should be a concern for every health-care professional. “It’s interesting how many people just assume that going home at the end of the day aching and fatigued is their lot in life,” he says. “As a doctor, you should be a phenomenal example of wellness and health for your patients. Patients can tell if you’re exhausted at 4:00 in the afternoon.”

Dr. Charles recently taught a course at Harvard that included a discussion of these issues. “We told the first-year fellows: If you’re not sitting up straight in the OR, if you’re not comfortable, you’ll eventually develop a nagging neck ache and headache. Eventually, it will interfere with your work and you won’t be able to focus as well. So, get comfortable, sit with good posture, get the chair right and get the microscope right. Your mother’s advice to sit up straight was correct! Don’t just show up and go to work. If your foot pedals are causing you to have a cramp in your quads, don’t just keep doing it and take NSAIDs; move the foot pedal until you’re sitting comfortably. If your chair cuts off the circulation in your legs, change chairs or the chair height so your legs are angulating over the sharp edge at the front of the chair.

“Your health affects your family and the people you work with,” he concludes. “If you happen to be a parent or grandparent, it might be nice to live long enough to help your family and watch them grow up. And if you don’t end up with a neck or backache and fatigue at the end of every day, you’re more likely to create a happy environment for your family and for those who work with you.”

1. Miller NM, McGowen RK. The painful truth: Physicians are not invincible. South Med J 2000;93:10:966-73.

2. Chatterjee A, Ryan WG, Rosen ES. Back pain in ophthalmologists. Eye (Lond) 1994;8(Pt 4):473-4.

3. Dhimitri KC, McGwin G Jr, McNeal SF, Lee P, Morse PA, Patterson M, Wertz FD, Marx JL. Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:1:179-81.

4. Chams H, Mohammadi SF, Moayyeri A. Frequency and assortment of self-report occupational complaints among Iranian ophthalmologists: A preliminary survey. Med Gen Med 2004;13:6:4:1.

5. Sivak-Callcott JA, Diaz SR, Ducatman AM, Rosen CL, Nimbarte AD, Sedgeman JA. A survey study of occupational pain and injury in ophthalmic plastic surgeons. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;27:1:28-32.