With additional MIGS options for treating glaucoma appearing every year or two, it’s becoming more of a challenge to decide which ones are worth adding to your surgical armamentarium—not to mention which one is most appropriate for a given patient. These questions are complicated by somewhat limited information about efficacy, especially in terms of one option versus another.

Ronald L. Fellman, MD, who practices at Glaucoma Associates of Texas and is an adjunct clinical professor of ophthalmology at North Texas Eye Research Institute and clinical associate professor emeritus at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, points out that a good way to think about the categories of MIGS procedures is to look at the outflow pathway they enhance (or create). “Right now,” he says, “the two main pathways are the conventional outflow pathway—the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal—and the subconjunctival pathway, using devices like the Xen and the PreserFlo, which is coming soon. Creating a pathway into the suprachoroidal space is another option, but with the CyPass no longer available, that’s off the table.” In addition, many surgeons consider cyclophotocoagulation of the ciliary processes, which reduces aqueous production, to be one of the MIGS procedures.

Here, surgeons with extensive MIGS experience share their insights about deciding which MIGS is the best choice for a given glaucoma patient, and offer some thoughts regarding how many options an ophthalmologist might want to have in his or her armamentarium.

The Canal-based MIGS

|

“Most MIGS are currently done in conjunction with cataract surgery,” notes Robert J. Noecker, MD, MBA, who practices at Ophthalmic Consultants of Connecticut and is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Yale and a full clinical professor at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut. “That’s partly because procedures like iStent and Hydrus are only approved for that, and partly because taking out the lens makes more space in the angle, which is beneficial for a lot of these patients as well.

“However, you also have to consider efficacy,” he continues. “More and more we’re seeing that the canal-based procedures like iTrack or Omni are helpful; in my experience, we get a little more efficacy when we do those procedures than when we just pop in a Hydrus or iStent. I see these as the next step up on the efficacy curve, before we give up on the angle structure and do a transscleral procedure like a Xen or the upcoming PreserFlo, or a trabeculectomy.”

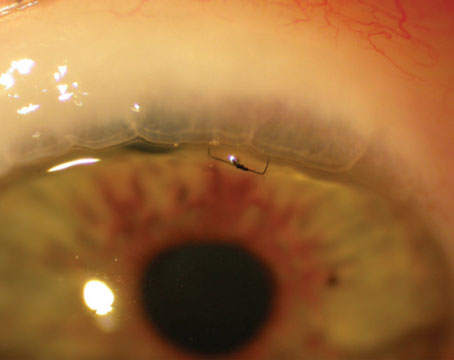

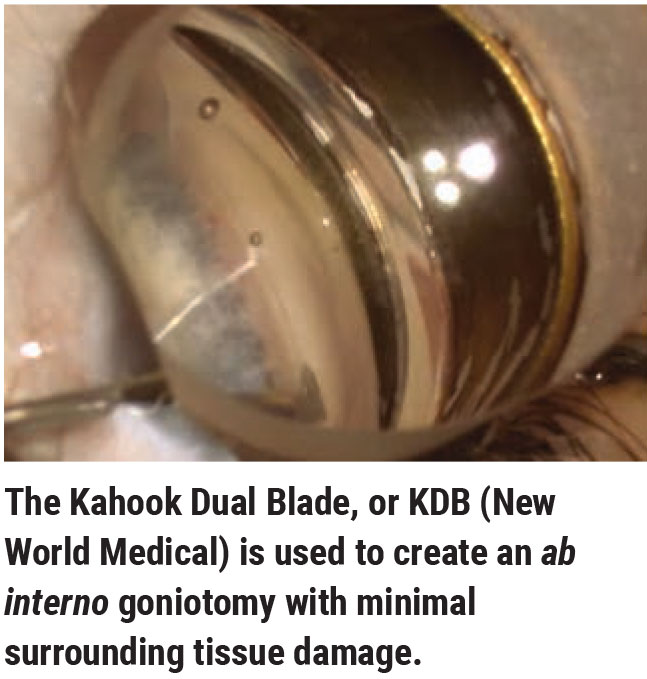

“Which MIGS is more efficacious is a more difficult question to answer, because the evidence supporting them isn’t the same,” notes Brian E. Flowers, MD, who practices at Ophthalmology Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “Some have much more robust quality data behind them than others. The ones with more supporting research can make claims about what they can do for the patient in much more precise fashion. Clinical trials are currently underway to try to determine the level of efficacy for Omni, but nothing’s been published yet. The Kahook Dual Blade doesn’t have any level-one randomized clinical trial evidence of its efficacy. On the other hand, the iStent Inject and the Hydrus both have high-level clinical evidence of their efficacy.”

Dr. Fellman agrees that deciding between MIGS can be tough because of the limited comparative data. “For example, we don’t know if it’s better to bypass the trabecular meshwork, cleave open the trabecular meshwork, viscodilate the trabecular meshwork or put in a scaffold to prop open the canal,” he says. “No study has compared all of those approaches in patients with mild, moderate and advanced glaucoma.

“The other problem is that the current FDA pathway for device approval in the canal space only involves eyes that have early to moderate glaucoma,” he continues. “These eyes are very different from eyes with advanced disease. That confounds a lot of ophthalmologists who are trying to decide the best thing to do for a patient; we don’t know how effective a MIGS will be in patients with different stages of glaucoma.

“It’s understandable that the studies were done that way,” he adds. “If you want to know whether something’s going to work in the canal, you don’t start by testing it on the worst cases. But it leaves a host of questions unanswered.”

Subconjunctival MIGS

“The great thing about the subconjunctival MIGS devices is that they control the amount of aqueous coming out of the anterior chamber, so that it’s just enough during the early postoperative period to leave the patient with an IOP of 8 to 10 mmHg,” says Dr. Fellman. “In addition, they make it possible to do filtration surgery under topical anesthesia with a minimally invasive technique. That’s a game-changer for many patients—especially the elderly, who can have a more rapid visual recovery with a topical anesthetic, are at less risk of bleeding while on blood thinners, and may avoid other potential complications.

“I think many comprehensive ophthalmologists are doing some type of canal-based surgery,” he continues. “Glaucoma specialists are using Xen, but I’m not sure about comprehensive ophthalmologists. Using the Xen means creating a bleb, and most comprehensive ophthalmologists don’t want to be bleb-ologists.

“In any case,” he says, “the subconjunctival MIGS like Xen tend to be reserved for patients with more advanced disease, for at least two reasons. First, we assume the collector channels are not very salvageable by the time the disease has become advanced. Second, even if the collector channels are working, studies have shown that when you open up Schlemm’s canal 360 degrees, 50 percent of the outflow resistance is still present. That’s why, no matter what kind of MIGS you do in the canal, the average pressure is still about 16 mmHg, not 12. That’s not low enough for some patients who have advanced disease.”

This raises a question: If you’re going through the sclera, why not just do a trabeculectomy? “A trabeculectomy is a brutal procedure,” Dr. Noecker points out. “For better or worse, we’re chopping a hole into the eye. That tissue is never normal after that. The eye gets rather inflamed and the postoperative course is very unpredictable.

“I’d say the worst thing that can happen with a Xen is that it could fail,” he continues. “In my hands, Xen patients don’t get extreme hypotony. If you use the ab interno approach, they don’t need sutures. They’re very unlikely to get a leak. These are things we have to look out for all the time after a trabeculectomy. The Xen allows us to rehabilitate the patient more quickly; they can usually go back to work in a week. With a trabeculectomy, that’s unlikely. The bottom line is that a Xen is a safer, less-invasive thing to do, and it can work as well as a trabeculectomy—although there’s a higher risk of failure because it’s a lower-flow system.”

Cyclophotocoagulation

“Technically, endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation could be considered the first MIGS,” says Dr. Flowers. “However, it has a higher risk profile than the Schlemm’s canal-based procedures because it causes some inflammation and has a longer visual recovery. I tend to use ECP more in cases of advanced glaucoma, although not every surgeon does.”

Dr. Flowers notes that the amount of ECP treatment makes a difference in its efficacy. “I’ve performed ECP long enough to know that if you really want a meaningful response, you have to treat pretty heavily,” he explains. “When you do treat more thoroughly, vision recovery is a little slower because there’s some inflammation; in fact, it may take four weeks to recover the expected level of vision. I know that many surgeons only treat up to 270 degrees—a sort of ‘ECP light’ treatment. We don’t have good evidence to show that the long-term effect of that is greater than the effect of cataract surgery alone.”

Dr. Flowers also points out the evidence supporting adding ECP to cataract surgery could be better. “There’s never been a prospective, randomized trial comparing cataract surgery alone to cataract surgery plus ECP,” he says. “Without that, you really don’t know how much added effect you’re getting from the ECP. The biggest trial I’m aware of was done by Stan Burke, MD, several years ago. It wasn’t randomized, but it was a large study with a lot of patients. Essentially, he found no difference between cataract surgery alone and cataract surgery plus ECP during the first three years postop. However, after three years the gain seen from the cataract surgery started to wear off, while the benefits of ECP didn’t wear off as much.

“ECP is definitely a tool in the armamentarium—possibly an underutilized tool—and I do use it in some cases,” Dr. Flowers concludes. “It clearly works; how much effect it has, and how many degrees of treatment is most appropriate is harder to answer. I do see a potentially bright future using ECP combined with other outflow MIGS procedures.”

Anatomic Issues to Consider

|

When choosing a MIGS procedure for a given patient, it’s worth considering the anatomic structure of the eye, the type of glaucoma you’re trying to manage and patient-related concerns. In terms of anatomic issues, the two main factors to consider are the narrowness of the angle and the size of the eye.

• The narrowness of the angle. “Out-side of average POAG patients, patients with angles that aren’t completely open are the most common ones we encounter,” says Dr. Noecker. “If you’re going to put an iStent or Hydrus in the eye, you want to make sure the angle is open. Both procedures are only approved for use in combination with cataract surgery, which in some ways makes things a little easier, because the cataract surgery will tend to open the angle a bit.”

Dr. Flowers agrees that the impact of a narrow angle is mitigated by whether or not you’re performing MIGS alone or in conjunction with cataract surgery. “Once you’ve done cataract surgery, the angle’s more open; then it’s not hard to perform any of the angle procedures,” he says. “If you’re talking about doing a standalone procedure without cataract surgery, you still have a few options that will be covered by insurance such as Omni and KDB, but those could be more difficult to do in a narrow angle.”

“In some cases the angle is partially closed and there are synechiae, so access to the angle isn’t great,” Dr. Noecker continues. “You can try to address that by doing something like ECP, which isn’t affected by the condition of the angle. Or, you can perform synechialysis in combination with the MIGS, or do a goniotomy-type procedure; ripping the trabecular meshwork open also removes any adhesions that are there. On the other hand, you can’t do canaloplasty and viscocanalostomy if synechiae are present.

“If it’s a young patient who’s going to remain phakic, I wouldn’t do any of the angle procedures,” he adds. “If they’re going to be pseudophakic, it’s a little bit wait-and-see, because sometimes when you take out the lens the angle opens up pretty nicely, giving you renewed access. Maybe you couldn’t do SLT in the office because the angle was so narrow, but after you remove the lens you have a much more open angle and that’s an option. On the other hand, if the patient is 30 years old and you want to leave the eye phakic, you’d probably want to do something like a Xen rather than place something in the angle that could later become occluded.”

Dr. Fellman says that whether a narrow-angle patient is a good candidate for a canal procedure such as a GATT (gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy) depends on just how narrow and diseased the angle appears gonioscopically. (Dr. Fellman’s practice originated the GATT procedure.) “If the patient has a narrow angle that’s led to chronic angle-closure glaucoma, and you find nerve damage, field loss and PAS, which means the iris has closed off the drain, that patient’s probably not a good candidate for a GATT,” he explains. “If someone has early narrow angle, is post-iridotomy and the angle is still open, then he’s a candidate for a GATT.”

Dr. Fellman notes that one factor that influences his choice about whether to implant a Xen or perform a trabeculectomy is whether the anterior chamber is narrow, along with pupillary block. “When you do a Xen, you don’t do an iridectomy,” he explains. “For that reason, in some patients with narrow angles, extensive PAS, uncontrolled pressure and significant nerve damage, you may favor a traditional trabeculectomy over a subconjunctival MIGS.”

• The size of the eye. “In small eyes you want to avoid situations where you have very low pressure, because these eyes can get choroidals and aqueous misdirection pretty easily,” says Dr. Noecker. “That’s one of the advantages of MIGS—hypotony is unlikely to happen, especially with the stents and canal-based procedures. The CyPass had some chance of producing short-term hypotony via increased uveal scleral outflow, but we can’t use that tool any more. The other thing about small eyes is that sometimes the anterior segment is kind of crowded, and that might make us avoid implanting a stent; it could be occluded simply because there’s not a lot of space in there. But this is one reason I like MIGS; in some ways we’re not as limited when choosing the best option for the patient.

“On the other hand, highly myopic eyes are good candidates for MIGS procedures, because higher-flow surgeries like trabeculectomies sometimes cause them to develop hypotony maculopathy, and they don’t bounce back,” he continues. “As a first-line option, I think any of the MIGS procedures are reasonable in those eyes.”

Dr. Flowers says if he’s choosing between non-penetrating MIGS, the only eye-size-related factor he sees as possibly having an impact is the formation of PAS. “I’ve done enough implants like iStent and Hydrus to see some PAS form around them,” he notes. “I can’t provide hard evidence that this would be more likely to happen in a small eye than a large eye, but it would stand to reason.

“In general, I don’t believe the size of the eye affects the functioning of the Hydrus, because it works via multiple mechanisms,” he continues. “Even if the distal lumen is partially obstructed, the device is still dilating and stenting open the angle and creating flow across septae. On the other hand, if you cover up an iStent completely, it’s possible it won’t work anymore.

“In the end, PAS probably affects all of these implants to some extent, but I’m not sure this would be significantly different in a small eye than in a large eye,” he concludes. “However, with large eyes, you may want to look to other options prior to considering a penetrating procedure like the Xen.”

The Type of Glaucoma

There’s scarce published evidence suggesting that one MIGS might be better than another when managing a given type of glaucoma. Nevertheless, many surgeons say they may adjust their choice based on the conditions associated with the specific type of glaucoma being addressed.

• Pseudoexfoliation or pigmentary glaucoma. “I think it’s reasonable to treat these patients the same way we treat primary open-angle glaucoma patients, with the understanding that the prognosis may be a little bit worse,” says Dr. Noecker. “The problems arise with these patients if we don’t intervene early and the patient starts to have a more aggressive form of the disease. If we do intervene early enough, I don’t believe the outcome will be much different than what you’d expect with a POAG patient.

“While these patients are usually myopes with deep angles, some of them have iris adhesions,” he adds. “In that situation I’d lean toward doing a goniotomy-type procedure, to maybe facilitate putting an angle stent in. In fact, I might do that to open the angle more even if it’s not possible to put a stent in.”

|

• Neovascular glaucoma. “Active neovascular disease is best treated with either cyclophotocoagulation done via micropulse or ECP, or by putting in a tube shunt—or both,” notes Dr. Noecker. “If it’s inactive neovascular disease and there are some synechiae left behind, the angle may be scarred without hope of re-establishing trabecular flow. But if the angle isn’t completely closed, and it’s early in the disease course, you can try to open the angle back up and hopefully get some kind of access to the trabecular meshwork.”

Dr. Fellman says that microinvasive surgeries tend not to be helpful in neovascular glaucoma. “In these glaucomas, where you have significant breakdown of the blood/aqueous barrier, microinvasive surgery doesn’t work,” he says. “Those patients are better off having a traditional drainage implant surgery with a shunt such as the Ahmed, Baerveldt, Molteno or ClearPath.”

• Congenital/juvenile glaucoma. “In many cases these patients have peripheral adhesions or many iris processes in the angle,” says Dr. Noecker. “If we can open those up, these patients can do pretty well. In these cases you might want to do a goniotomy, either by itself or in conjunction with a stent.”

“We’ve learned that younger patients do extremely well with GATT,” adds Dr. Fellman. “This includes infants and patients up to their 40s who’ve had glaucoma for many years.

“It’s well-known that infants with primary congenital glaucoma do well with a 360-degree trabeculotomy,” he continues. “One reason for that is secondary canalogenesis, which is a reformation of the canal after trabeculotomy that typically occurs in patients less than a year old. They have a success rate of close to 90 percent, which is better than any other glaucoma procedure. The success rate in juvenile glaucoma is slightly less, but still very good. This is probably related to better elasticity in younger outflow systems.”

• Uveitic glaucoma. “We have a lower expectation of success using MIGS in uveitic glaucoma patients,” says Dr. Noecker. “We’re less likely to get the patient off of all medications and achieve physiologic target pressure. At the same time, these patients may begin to hyposecrete and develop hypotony. But certainly if the eye has a bunch of adhesions and synechiae, we’re going to get away from stents. We may put in a Xen or perform a more traditional glaucoma surgery such as a tube shunt. We’d avoid ECP or micropulse, because they induce more inflammation and the outcome is more unpredictable.

“The biggest question is, will the procedure do enough?” he continues. “Uveitic glaucoma is hard to treat with any approach. A patient with a lot of synechiae or adhesions as a result of the inflammation probably has low-grade iritis and could be a steroid responder. But if the angle is still pretty open, I think it’s worth trying our typical algorithm. On the other hand, as you get more into the severe patients, where the disease is still active, many patients will be steroid responders. You can get caught in a situation where you need to treat their inflammation, but treating it with steroids makes their IOP go up. That’s often what prompts us to do surgery.”

“If a patient has preop inflammation, by definition you have a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier,” Dr. Fellman notes. “Inflammation means that your anterior segment is revved up and may close off whatever you do. Eyes that have a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier are more likely to bleed and have fibrin that will block a microstent, so those eyes tend to do better with classic drainage implants where the inner lumen is pretty big compared to a microshunt. That’s why, if there’s a lot of preop inflammation, I tend to shy away from doing subconjunctival MIGS such as a Xen.

“If your patient tends to have controlled inflammation and the surgeon is committed to canal-based MIGS, you want to choose a MIGS procedure that causes the least amount of breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier,” he continues. “You’re more likely to get inflammation if the patient has bleeding, as happens with a GATT procedure, than from a minimal trabeculotomy like that created with a Trabectome or Kahook Dual Blade. So you want to tailor your procedure based on how much inflammation the patient has preop and how much you expect postop.

“Fortunately,” he adds, “inflammation isn’t a long-term issue with MIGS procedures, if they’re performed correctly.”

Other Considerations

|

Other factors that could influence a surgeon’s choice of MIGS include:

• Previous surgery. “If the patient has previously had cataract surgery, that usually means we won’t be doing an iStent or Hydrus—although there are exceptions,” says Dr.

Noecker. “In fact, such a patient may already have an iStent or Hydrus in the angle. Our next option is a canal-based procedure. The most benign one to do is an iTrack—an ab interno canaloplasty/viscocanalostomy. We could also use the Omni system or do a goniotomy-based procedure like the Kahook Dual Blade.

“If the patient had other types of prior surgery, such as retinal detachment surgery, we won’t do a Xen because the conjunctiva is probably scarred,” he adds. “It might be worth trying a canal-based procedure, but I’d have a low threshold for putting in a tube.”

Dr. Fellman notes that GATT is a good option for patients who’ve already had a tube or trabeculectomy. “You can still go back and open up the natural trabecular outflow system quite successfully in these eyes,” he says. “We’ve been surprised how well these eyes do with GATT.”

• The patient’s ability to return for follow-up. Dr. Noecker says he doesn’t worry about how many years a patient may have left to live. “An older patient may live many more years, no matter what age they are,” he points out. “However, you might worry about their ability to return to the office for follow-up. If the patient’s going to have a hard time returning, that’s where we lean toward doing a MIGS. A transscleral micropulse may be a good option because the postop care is pretty limited. There’s no risk of infection.

“As is often true with glaucoma surgery, the hardest part isn’t doing the surgery, it’s troubleshooting postop,” he adds. “You have to set yourself up for postop success. For example, if you do a Xen, you have to see the patient postop to watch out for scarring and maybe apply additional mitomycin-C. If the patient can’t manage that, then the surgery is probably going to fail.”

• The patient’s fears and expectations. Dr. Fellman notes that another issue when choosing which MIGS to perform is the patient’s perception of the surgery and what information they’ve read on the internet. “This generates anxiety and sometimes impractical expectations,” he explains. “So, you have to tailor your choice of procedure not only to the patient’s level of disease and anatomy, but also to their anxiety about the procedure.

“If you’re not inclined to do subconjunctival MIGS and you’re faced with a patient whose disease is more advanced, you can still offer a canal-based MIGS,” he notes. “You’ll have to make sure the patient understands that there will still be a lot of inherent resistance left in the canal system, and that a canal-based MIGS may not be sufficient to prevent further visual field damage, requiring a more aggressive subconjunctival procedure later.”

• The impact of COVID. “Unfortunately, the pandemic has made it risky for patients to be in your office,” notes Dr. Fellman. “That means you might want to avoid doing a MIGS procedure that requires a lot of postoperative follow-up, such as a Xen, and lean towards a less-invasive canal-based procedure.”

The ABCDEF System

Dr. Fellman has laid out a series of points to keep in mind when choosing a MIGS procedure, represented by the mnemonic device: ABCDEF.

“A stands for the angle, which is a good starting point,” he explains. “If you’re thinking about MIGS, look at the angle carefully with your favorite gonioprism. This will not only help you decide what to do, it will help diagnose the correct type of glaucoma. Also, some angles are fairly complex. You’ll need to be able to identify the angle landmarks well to proceed with canal-based MIGS.

‘A’ can also stand for the patient’s age, and the patient’s level of anxiety, both of which can influence your choice of procedure.

“B stands for the blood-aqueous barrier,” he continues. “If the blood-aqueous barrier is bad for any of 100 reasons, including neovascular glaucoma or trauma or uveitis, you probably shouldn’t do a subconjunctival MIGS. However, you can carefully consider a canal-based MIGS or a classic drainage implant.

“C stands for the conjunctiva,” he says. “If the conjunctiva is scarred badly, then you don’t want to do a subconjunctival MIGS like a Xen because it will probably fail. You typically need virgin conjunctiva for this type of procedure. Unfortunately, today ‘C’ also stands for COVID. You don’t want to do a procedure where you need to see the patient every day, or every other day for postop maintenance, because you’ll expose the patient to more chances to be infect with COVID.

“D stands for the disc,” he continues. “If you have a lot of disc damage, you have to start thinking more about subconjunctival MIGS, because even if you eliminate all the resistance in the trabecular meshwork, you’ll still have 50 percent of the outflow resistance left. Evolution has designed the outflow system to have multiple checks and balances in it that err on the side of slightly elevated pressure, to avoid hypotony at all costs. That’s why you typically don’t get a pressure of 10 mmHg when you completely open up the canal. The only way to get a larger drop in pressure will be through a subconjunctival MIGS—at least until we have an approved way to access the suprachoroidal space.”

|

Dr. Fellman points out that one of the reasons some ophthalmologists are skeptical of MIGS is that the canal-based procedures rarely produce a pressure lower than the mid-teens. “Ophthalmologists know that the episcleral venous pressure is about 10 mmHg,” he says. “So, if we bypass the trabecular meshwork or stent open the canal with the Hydrus, why isn’t the result a pressure of 10 mmHg? The problem is, there are many distal collector channels that aqueous has to go through before it gets into the episcleral veins. And, no matter what you do, Mother Nature has set up our eyes to prevent hypotony. So you’re not going to get 10 mmHg; you’re going to get a pressure in the mid-teens.

“Occasionally you can get lower pressures via a canal-based MIGS in a patient with congenital or developmental glaucoma,” he notes. “That’s probably because the elasticity is better, and infant eyes undergo secondary canalogenesis and tend to recreate a more normal drainage system without scar tissue. But as we all know, when you get old, your elasticity goes out the window. Everything gets fibrotic.

“E stands for your level of expertise,” he continues. “What are you comfortable doing? Fortunately, if you decide you’d like to develop your expertise in a MIGS procedure that’s not already part of your armamentarium, you have many avenues of support, from the manufacturers, to online videos, to watching other surgeons do these procedures live.

“F stands for the field,” he concludes. “Whether a canal-based MIGS is sufficient or a subconjunctival option is more appropriate depends in part on how well the patient’s native outflow system is functioning. I find that how well patients are functioning visually correlates better with their visual field than with OCT findings on the disc. Patients who have advanced field loss tend to do better long-term with subconjunctival filtration.”

Strategies for Success

Surgeons offer these additional suggestions when choosing a MIGS procedure:

• First, decide what you don’t want to do. Dr. Fellman says that this is a big part of deciding what you do want to do. “After doing surgeries for many years, you learn what makes people get worse and doesn’t work long-term,” he explains. “You don’t want to go down that road (especially in a monocular patient). So I first decide what not to do. That eliminates a lot of options.

“For example, suppose you have a patient on a blood thinner and you can’t stop that drug,” he continues. “You don’t want to do a GATT on that patient because in some people Schlemm’s canal contains a lot of blood. If the patient has a cataract, you’ll be more likely to choose a phaco-iStent, because you’ll get the least amount of bleeding; you’re bypassing the meshwork instead of cleaving it.

“You have to look at the overall systemic profile of the patient, the patient’s level of anxiety and your level of expertise,” he concludes. “These factors should all influence how you decide to proceed.”

• Try to leave future options open. Dr. Flowers says one factor that influences his choice of MIGS is making sure that any additional surgeries that may need to be done in the future are still feasible. “As a glaucoma specialist I always want to be thinking multiple surgeries ahead,” he notes. “Generally speaking, nothing lasts forever. If you do a 360-degree trabeculotomy, the angle’s pretty much done. You can’t go back and do anything else involving the angle. On the other hand—theoretically at least—if you put in an iStent or Hydrus or perform canaloplasty, you’ve only treated part of the angle. You still have more angle you can go back and treat later.

“So looking at Omni going forward, I think a lot of people may end up doing a 360-degree canaloplasty and a 180-degree trabeculotomy,” he continues. “That at least leaves you with some angle to work with in the future if you need to do something else. However, it will take some time for the research to show us whether or not that’s the right decision.

“Our practice is currently involved in clinical trials of the Omni procedure, as well as a Hydrus study, and we just finished our second iStent Inject study,” he adds. “So, people are trying to answer these questions. The point is, when choosing a procedure, you want to be ready for the next thing. You don’t want to close any doors.”

“One of the nice things about MIGS is that most of them don’t destroy future options,” Dr. Noecker notes. “If you do a canal-based procedure, you can still do pretty much anything else after that.”

• Consider combining MIGS. Dr. Noecker points out that attacking a problem in more than one way is something ophthalmologists routinely do with glaucoma medications. “Some patients are OK with one medication, while others need a couple of medications to keep the pressure down. I think it’s the same concept,” he says.

“The risk of adding an extra MIGS procedure isn’t that great,” he continues. “For example, I might do an iTrack procedure to open up the canal and then put in a Hydrus to hold it open. Or, combine ECP and a stenting or canal procedure. Of course, we never know for sure what will work for an individual patient until we’ve tried it. But in some ways you’re hedging your bets and being a little more aggressive by doing a combined procedure.

“The reality is, glaucoma patients do better with lower pressures; they’re less likely to have optic nerve damage,” he adds. “So, we’re always looking for an opportunity to push the pressure down another notch, especially in patients we’re more concerned about. That’s when we’re more likely to combine a couple of MIGS procedures.”

How Many MIGS?

One factor that should influence your decision about how many MIGS to offer is the level of disease you routinely face in your practice. Clearly, the different MIGS procedures have somewhat different levels of efficacy—although the comparative efficacy has often not been established in clinical trials.

Dr. Noecker sees MIGS as falling into four categories. “Stents like the Hydrus and iStent are probably the lowest-risk thing to do, but they may be on the lower end of the efficacy spectrum,” he says. “The next step up would be the canal-based procedures and goniotomy; that category would include the iTrack, Omni system, KDB and Trabectome. When you’re opening up the canal, there’s a little more risk—a little more blood and inflammation—but also more efficacy. And, you can use these as a standalone procedure if you need to come back after the cataract is done.

“The third category is doing a transscleral or subconjunctival procedure like the Xen or PreserFlo—which we should have soon—or an ExPress shunt,” he continues. “A fourth category is reducing aqueous production. This means some sort of cyclophotocoagulation procedure, whether it’s done internally via ECP, if you’re comfortable with that, or externally with the Micropulse.

“If you treat a lot of glaucoma, I think it’s worth being able to do something from each category,” he says. “It’s good to be able to do at least a few of these. You can refer patients out when you reach the level of complexity that you don’t want to deal with. Some comprehensive surgeons are very comfortable with the iStent and ECP. Both of those have been around for a long time. If you deal with moderate glaucoma, you probably should offer one of the canal procedures as well, and possibly the Xen-level options.”

“I think how many MIGS you should offer depends on who you are,” says Dr. Flowers. “If you’re a glaucoma specialist, I think you want to have at least one from each category in your toolbox: A Schlemm’s canal procedure; a supraciliary procedure (once one becomes available again); a way of doing cyclodestruction, either with ECP or Micropulse; and a filtering option. On the other hand, I think a general ophthalmologist should be able to perform at least one Schlemm’s canal-based procedure. One could argue that one is enough, because there’s no strong evidence of a huge difference in efficacy between them.

“Ultimately, I think people have to do the procedure they’re most comfortable with,” he concludes. “Some might argue that the iStent is easier to put in than the Hydrus, but it’s not necessarily easier to get in the exact right place. When you put in the Hydrus, you know you’re in Schlemm’s canal, whereas with the iStent Inject, you can’t be as certain. In terms of efficacy, their data was similar in randomized clinical trials. So, surgeons have to develop a comfort level with these procedures and then ultimately do the one they’re most adept at performing.”

“What most surgeons end up having in their armamentarium depends on what they’re comfortable with, and their patient population,” agrees Dr. Fellman. “If you’re mainly dealing with early glaucoma, then you may be happy with only offering the iStent, even though you’re only tapping into a few adjacent collector channels. That may be all you need. But if you’re treating more moderate glaucoma, then the Hydrus might be a better choice because it may access more collector channels. If you’re managing more advanced glaucoma patients, then creating a new subconjunctival drainage system should be part of your skill set.”

It’s Always Worth Considering

“Every glaucoma surgery has a risk profile,” notes Dr. Flowers. “The reason MIGS was invented in the first place was to have a very safe surgical option to address glaucoma—safety first, efficacy second. That’s how I decide which approach I’m going to take: Which surgery has the appropriate level of risk for this particular individual? The second question is, how much efficacy do I need?

“Every patient is unique, of course,” he continues. “If a patient has moderate nerve damage and is on three medications and the pressure is controlled, the patient doesn’t necessarily need anything—but she could certainly benefit from something. If you do a Schlemm’s canal-based procedure, be it an iStent inject or Hydrus or KDB, you’re going to improve her quality of life and have the patient on fewer medications, with almost no increased risk.”

“I believe surgeons should consider doing a MIGS procedure in every patient who’s actively being treated for glaucoma,” Dr. Noecker adds. “Among other things, if you have glaucoma you’re at greater risk of a postop IOP spike following cataract surgery—especially in cases of secondary glaucoma such as pigmentary glaucoma—and MIGS can help prevent that. You’re also more likely to be a steroid responder. A few patients may give you a reason to avoid combining MIGS with cataract surgery, but in most cases the risk is very small. I think adding a MIGS is a ‘best practice’ choice.”

Dr. Noecker reports financial ties to BVI, Nova Eye Medical, Glaukos, Allergan, Santen, IOP Inc, Sight Sciences and Ivantis. Dr. Fellman is a consultant for Beaver-Visitec, Alcon, Sanoculis and Olleyes. Dr. Flowers has consulting relationships with Alcon, Glaukos, Ivantis, Sight Sciences and InnFocus.