“Commercial availability is not yet known, but should be in several months,” says Jon G. Dishler, MD, of Dishler Laser Institute, Denver, Co., U.S. medical monitor for the VisuMax IDE Study. Current users of the VisuMax laser will need to upgrade their existing software. New users will need to complete SMILE training before and during their first cases.

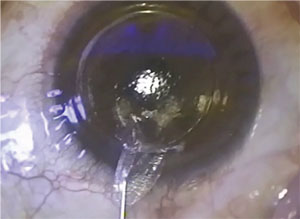

SMILE requires the use of the Zeiss VisuMax femtosecond laser to create a disc-shaped lenticule inside the cornea, which is then extracted through a 2- to 3-mm corneal incision. Extraction of the lenticule flattens the cornea, correcting the myopia.

|

| In SMILE, removing a lenticule flattens the cornea. Image: Jesper Hjordal, MD |

Because SMILE leaves behind a smaller entry wound, there’s less disruption to the corneal surface than with LASIK. This may mean faster recovery and less chance of postop dry eye. SMILE candidates must be at least 22 and have documented stable manifest refraction over the past year. SMILE candidates should be -1 D to -8 D with ≤ -0.50 D cylinder and MRSE -8.25 D in the affected eye(s). “Particularly well-suited candidates are ones where a corneal flap would best be avoided, such as the military or police,” says Dr. Dishler.

“The approved procedure doesn’t correct astigmatism,” he notes, “so patients who are satisfied with spherical soft contact lenses within the approved range are good potential candidates.”

For the study, 336 eyes underwent SMILE for nearsightedness at five investigational sites. “There was excellent and stable correction of refractive error in the clinical trial,” says Dr. Dishler. Of the 328 participants evaluated at six months, 88 percent had uncorrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better, with all but one seeing 20/40 or better uncorrected. Patients also experienced rapid visual recovery with little discomfort. Intraoperative complications included difficulty removing the corneal tissue and loss of suction. Postop complications included debris at the tissue-removal site, dry eye, glare and halos.

Although no enhancements were needed in the study, Dr. Dishler states that they could be performed by PRK if needed.

A clinical trial is currently underway in myopic astigmats, but hyperopic patients will have to wait even longer to see if SMILE is an option for them. “There is an international study on treatment of hyperopia,” Dr. Dishler says, “but this has not been studied yet in an FDA clinical trial, and we have no information on future plans.”

Patients Unaware of Telemedicine

In August, researchers at the University of Michigan Health System examined the efficacy of diagnosing and monitoring diabetic retinopathy via telemedicine. While they found that telemedicine is indeed effective, the study also discovered that only a small portion of the participants had previously used it or even heard of it.

In the study, 97 percent of the participants hadn’t heard of telemedicine, which the researchers believe to be reflective of most U.S. citizens. After being introduced to telemedicine, 32 percent of participants were still either unsure or opposed to participating in telemedicine for DR screening. University of Michigan’s Maria Woodward, MD, notes that previous patient experience makes a difference: “If patients have a strong relationship with their eye doctor and have been living with diabetes for a number of years independently, they are less interested in telemedicine,” she says.

Dr. Woodward also attributes skepticism of telemedicine to lack of knowledge about the process. “Certainly there’s the education aspect, too, as in knowing that this is really safe and effective for patients,” she says. “There has been plenty of evidence in the literature that doing diabetic screening by telemedicine is as safe as going to an eye doctor for the same exam.”

Dr. Woodward notes that telemedicine also isn’t very popular due to its cost. “Telemedicine programs incur a lot of cost,” she explains, “so systems that can see the long-term benefits of preventative medicine have this program in place. Those systems that are set up in such a way that they see the same patients regularly see the power of long-term prevention. In other systems where patients move between systems and providers, there’s a lot of infrastructure cost to set up these programs. Because of this, it really hasn’t been done in the U.S. until now, when the cameras and the technology have allowed the cost of telemedicine to drop to the point that it makes sense to set up these programs for patients.”

Despite its cost and patient unfamiliarity, telemedicine has been helpful in screening for diabetic retinopathy. “The benefit to the patients with diabetes is the convenience,” Dr. Woodward says, “and that convenience is twofold: One, there is the convenience due to time saved; and two, the patients typically don’t have to be dilated for a telemedicine exam, so it’s more comfortable for them.” The study also concluded that telemedicine programs should focus on individuals who have limited access to care, as these programs would allow patients to complete screenings from the comfort and convenience of their own homes. REVIEW