Fifty years ago, only a handful of options existed for treating glaucoma. Today we have multiple medications, numerous surgeries, new laser options and new tools and devices. But as new treatment modalities appear, surgeons have to decide whe-ther to incorporate them into their armamentariums—and perhaps more important, how to incorporate them.

“My treatment paradigm has definitely shifted in recent years,” says Thomas W. Samuelson, MD, a founding partner and attending surgeon at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis and an adjunct professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota. “For the better part of my career, it was medications, then laser, then surgery. That’s changed completely.

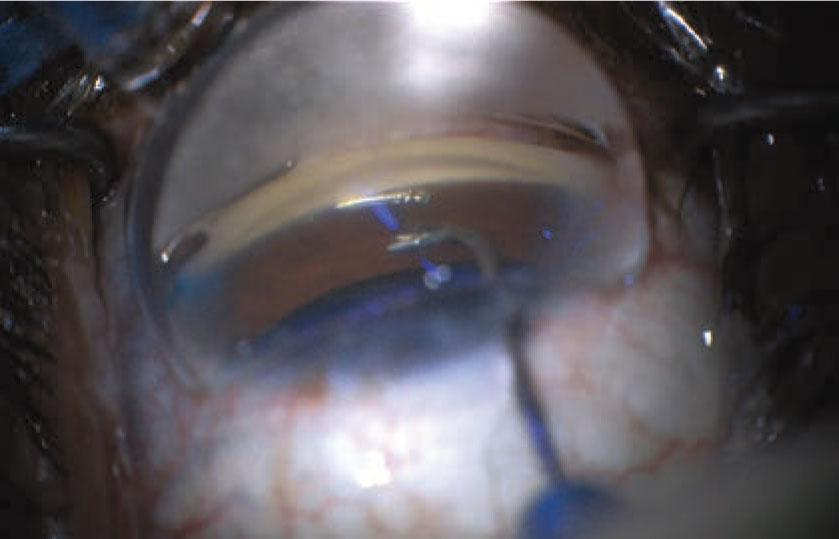

|

| MIGS procedures such as the Hydrus make useful adjuncts to cataract surgery as a first-line treatment for a new glaucoma patient with a cataract, but other patients are likely to shy away from surgery as a first option. |

“One of the first things that triggered that change was the realization that cataract surgery helps lower eye pressure,” he explains. “We have definitive, level-one evidence that demonstrates this. So today, one of the first metrics I look at when I see a new patient with glaucoma is the status of the native lens. Does the patient have a cataract, and is it ready to be removed? If so, then we go down one pathway: cataract surgery, plus or minus MIGS. If there’s no cataract that’s ready to be removed, then we go with medications or laser. And now we even have two different options with medications: eye drop therapy or the implantable, sustained delivery device, Durysta.”

Joseph F. Panarelli, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Service at NYU Langone Health in New York City, notes that new options rarely become the new first-line treatment right off the bat. “Whenever a new treatment option becomes available, many of us slowly work it into our treatment regimen,” he says. “This often means not using it as a first-line treatment [in the beginning], because we want to gain more experience with it and see what the risks and benefits are in our patient population. Phase III results and other study data are very helpful in guiding us early on, but those results are not generalizable. Therefore, many of us will only resort to these treatment options when our usual topical medications don’t get the job done. Meanwhile, the patient’s preferences are still a key factor. For that reason, the decision-making process is shared with the patient.”

Here, surgeons with extensive experience treating glaucoma share their thoughts on the current state of glaucoma treatment protocols.

New Topical Drops

Among the recent entries into the field of treatment options are several newly approved topical drugs, including rho kinase inhibitors and latanoprostene bunod.

Albert S. Khouri, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of resident education and the glaucoma service at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, was involved in the clinical trials of the new rho kinase inhibitors and latanoprostene bunod. “The last new class of drugs, the prostaglandins, appeared back in 1996,” he points out. “Between then and 2018, when Rhopressa and Vyzulta appeared, we only got new fixed combinations of existing medications. Today, we have Rocklatan, the only FDA-approved fixed combination in the U.S. that includes a prostaglandin. Previous combinations incorporating prostaglandins didn’t meet clinical trial endpoints, so they weren’t approved by the FDA.”

Dr. Khouri believes these recent developments may shift the equation back toward favoring drug treatment options. “Among other things, we finally have medications that target the trabecular meshwork,” he notes. “All of the previous medications we’ve had bypass the trabecular meshwork, either by reducing aqueous production or by diverting aqueous away from the trabecular meshwork into the uveoscleral outflow pathway. In contrast, rho kinase inhibitors enhance the trabecular meshwork, allowing more aqueous to flow through the traditional outflow channel. It’s even possible that these new drugs will have an impact on the natural history of the disease if introduced early in the disease process. Time will tell.”

Dr. Khouri notes that the Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines from the American Academy of Ophthalmology suggest that your first medication should deliver a 20- to 30-percent reduction in IOP from baseline. “To achieve that, most physicians typically start with a prostaglandin like latanoprost,” he says. “It’s effective; it’s easy to use; it’s well-tolerated. Also, it’s used once a day, which is good for adherence—very important with a topical therapy. The prostaglandins have minimal systemic side effects, although there are some ocular side effects. Generally the discontinuation rate is pretty low, so they’re well-tolerated. These brand new medications are well-positioned to become first-line options.”

“There’s an added potential for lowering IOP with the use of drugs like Rocklatan and Vyzulta, compared to a prostaglandin alone,” says Sanjay Asrani, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at Duke University School of Medicine and director of the Duke Eye Center of Cary in Durham, North Carolina. “So, there’s a possibility that one of these drugs used first-line could achieve the target pressure. That could change the game. The question is whether they’ll work for everybody, and whether they’ll be tolerated by everyone. That will have to be determined by trial and error.”

“Netarsudil has a great mechanism of action; it’s greatest limitation is tolerability,” notes Dr. Samuelson. “Hyperemia is very common, and a significant number of patients haven’t been able to tolerate it. But for patients with more advanced disease, or patients who have limited other options, I think it’s a great drug for lowering pressure. Patients that already have physiological pressures tend to respond better to netarsudil than some other agents, based on its novel mechanism.”

Perhaps more problematic, in terms of widespread acceptance into the glaucoma treatment regimen, are the issues of pricing and reimbursement. “Many of these drugs aren’t covered by insurance unless you’ve tried another drug first,” Dr. Asrani notes. “In the future, if a patient needed a significant pressure drop and could tolerate the new drugs and reimbursement wasn’t an issue, they might be one-and-done—a single eye drop per day. But right now many insurances are still requiring that the patient try a prostaglandin first.”

A Standalone MIGS for First-line Treatment? Although many MIGS procedures have only been approved for use in conjunction with cataract surgery, a few can be done as standalone procedures. Would they make sense as first-line glaucoma treatment options? “I don’t think patients will be inclined to undergo MIGS without first trying drops,” says Sanjay Asrani, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at Duke University School of Medicine. “Even if it’s a MIGS procedure, there’s some risk associated with it, and some cost, and it requires a trip to the OR. You need to enter the anterior chamber, and there’s always the risk of endophthalmitis or hyphema. Those risks are small, but real. In contrast, SLT and medications don’t have those risks.” However, he notes that a noncompliant patient might be an exception. “The patient may have demonstrated noncompliance in other areas of medical care,” he says, “or you know that the patient is at risk of losing their insurance and not being able to afford long-term medical therapy. In that situation it may be appropriate to consider proceeding with MIGS as a first choice.” “I find it hard to justify a standalone MIGS procedure as a first-line choice,” says Albert S. Khouri, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma service at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. “However, if you have patients who aren’t on target, they’ve already had their cataract done and they want to avoid a trabeculectomy or subconjunctival procedure like a Xen or tube shunt, then you could discuss this option with them. Of course, there are some patients, such as those with juvenile glaucoma, younger patients, and those with pigment dispersion or exfoliation glaucoma, for whom goniotomies tend to be more effective. In those cases it might make more sense to attempt a goniotomy.” —CK |

“We’ve had difficulty getting payors to price netarsudil so that patients can afford it,” Dr. Samuelson adds. “Also, the tolerability is an issue. However, I do like to find out if a given patient is able to tolerate it, because it’s a great option with a very favorable and novel mechanism of action if the patient can tolerate it and get it for an affordable price.”

He notes that latanoprostene bunod seems to have better tolerability than netarsudil. “It’s pretty uncommon that patients don’t tolerate it,” he notes. “It’s basically latanoprost with a nitric-oxide-donating component; that gives it about a 1.3-mmHg advantage over standard latanoprost. But it tends to be very pricey, which can be a problem. But despite these concerns, I’ve found netarsudil and latanoprost bunod to be important options to have for patients with moderate or severe glaucoma.”

Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty

SLT has been a treatment option for glaucoma for a number of years, but the recent data from the LIGHT (Laser for the Initial treatment of Glaucoma and ocular HyperTension) trial, conducted in the United Kingdom, has caused many ophthalmologists to rethink where this option belongs in their treatment protocol.

“Previous studies demonstrated that laser was about as effective as, say, a prostaglandin analogue,” Dr. Samuelson says. “But that knowledge didn’t change practice patterns as much as the data from the LIGHT trial did, because in the LIGHT trial, not only did the laser group do as well as the drop group, they did better in many ways. They had fewer subsequent surgeries, including less need for subsequent cataract surgery. Patients did better both economically and medically. Their glaucoma was better controlled if they had laser first.

“That caused a paradigm shift for patients needing initial treatment,” he continues. “We offer those patients first-line laser much more often now. And because we have more confidence in our story—that is, we have a prospective, randomized trial that showed laser is at least as good, and probably better than eye drop therapy—we can not only be confident in offering it, but confident in recommending it.”

Nevertheless, it appears that SLT isn’t yet displacing a prostaglandin as the most frequent first-line treatment, for a number of reasons ranging from patient perception to the difference between trial data and real-world clinical realities. “Most physicians are aware of the LIGHT study findings and support the idea of using SLT as an initial therapy, but in real-life practice, not that many of us actually do,” confirms Dr. Khouri. “For one thing, in the U.K., where the LIGHT study was conducted, the health-care system is very different from here in the U.S. For another thing, it’s easier for many patients to accept the use of an eye drop than the laser. I discuss SLT with patients upon diagnosis so they know it’s an option, but for some, the word ‘laser’ triggers a negative response.”

Dr. Asrani agrees. “The main reason most patients are still being treated with drops first is that not everyone is comfortable starting with a procedure,” he says. “Recommending a procedure at your first meeting may be perceived as an aggressive stance. Furthermore if a drop doesn’t work, the patient doesn’t usually perceive that as being your fault. But if SLT doesn’t work, the patient may assume that you didn’t do a good job. And of course, some doctors may not be very conversant with doing SLT, making them inclined to go straight to drops.”

Dr. Samuelson points out two caveats about the LIGHT trial data. “It’s important to realize that in the LIGHT trial, about a third of the patients that received laser were ocular hypertensives,” he says. “They weren’t even categorized as glaucoma patients. So, this was a patient population with pretty mild glaucoma. This means that the results of the LIGHT trial can’t be extrapolated to patients with more severe glaucoma. Many of us looked at the results of the LIGHT trial and thought, ‘I don’t see response rates as good as those reported in this trial.’ The reason may be that we’re not used to doing laser on such early glaucoma cases. If your patient has much more severe glaucoma, you can’t necessarily expect to see the same response.”

So what’s the current reality regarding SLT? “What I think has really changed because of the LIGHT study is that we’re now typically offering SLT after the first medication,” Dr. Khouri says. “Many years ago we’d discuss SLT with patients when they weren’t reaching their target on the second or third medication. Now, if the pressure isn’t on target after a prostaglandin, for example, we quickly discuss SLT.”

Dr. Samuelson notes that he rarely tries to persuade the patient to do SLT. “I offer it and maybe give a gentle recommendation, but if the patient is resistant to having laser as their initial treatment, I don’t push it,” he says. “I’d say about half of these patients choose to start with the laser treatment. When patients are indecisive or hesitant, I just take out my business card and write down ‘the LIGHT trial (Laser for the Initial treatment of Glaucoma and ocular Hypertension Trial)’ and hand it to the patient. I say, ‘We’ll start with this drop. If you’re interested, go online and take a look at this trial that was conducted in the U.K. If you change your mind and you want to go with laser as an alternative to the drop, just give me a call.’ ”

Where Do MIGS Fit In?

Choices regarding when to offer minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries to a glaucoma patient have been largely influenced by the FDA labeling. “Several of the MIGS options are only approved for use in combination with cataract extraction, although a few can be done as standalone procedures,” Dr. Khouri says. “The way I approach it is, any patient in need of cataract extraction who is being treated for glaucoma is a candidate for a MIGS procedure.

“In the past, once medications and laser failed to meet the target pressure, your discussion with the patient would be a trabeculectomy or a tube,” he continues. “Those are more effective than phaco plus MIGS, but they’re also more risky. Their complication rates are higher, and some of the complications can be grave. The phaco-MIGS procedure can keep the pressure in check for some period of time, and hopefully prevent or delay the need for a riskier procedure.

Will Drugs Ever Become Obsolete? One thing most surgeons seem to agree on: Topical drops will always need to be an option, no matter what the future holds. “I don’t see a future for glaucoma treatment in which drugs won’t be around,” says Sanjay Asrani, MD, director of the Duke Eye Center of Cary in Durham, North Carolina. “Everyone knows they work, and they’re the least risky tool we have in our armamentarium. You can try different combinations, and you can stop them if there’s a problem. The biggest issue is delivering them. If a drug-delivery platform could reliably control the pressure for a year, that could be a game-changer.” Albert S. Khouri, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma service at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, also believes that drops will never disappear. “SLT and MIGS, for the most part, target the traditional outflow pathway,” he notes. “If the outflow system has collapsed, or is dysfunctional, they won’t reduce the pressure to levels that some patients with glaucoma need. Also, every surgery is associated with risk, no matter how micro-incisional or minimally invasive it is, and the outcomes are determined in part by the healing response, which is variable. That means that doing away with medical therapy would be difficult—at least with our current procedures.” Joseph F. Panarelli, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Service at NYU Langone Health in New York City, agrees. “Topical medications are a safe, effective, and reliable way to slow disease progression,” he points out. “They’ve worked for us for decades. They may not be the answer for every patient, but they are the answer for a large number of patients.” Dr. Asrani says he thinks it’s possible that some procedure will be invented that can lower IOP significantly without much risk. “If that happens, then it’s possible that many people won’t need drugs anymore,” he admits. “However, not everyone has access to an operating room, and not everyone is willing to take the risks associated with a procedure.” “Drugs will always be necessary,” agrees Thomas W. Samuelson, MD, a founding partner and attending surgeon at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis. “We don’t have any one treatment modality that’s good enough to be the only treatment modality. Even with surgery, drugs and laser, some patients still lose vision from glaucoma. “Whatever the future holds,” he adds, “the options we have now are much better than when I started practice. It’s been a great privilege to watch it all play out.” —CK |

“The uncertainty with MIGS—particularly with the procedures that help get aqueous past the trabecular meshwork—centers around the condition of the traditional distal outflow from the eye,” he notes. “If the distal pathway beyond the trabecular meshwork is still preserved, then you’ll get a nice response from your MIGS procedure. But if the distal pathway is dysfunctional, you may not get a response beyond what the phaco would have provided by itself. Unfortunately, you’re only going to find out how good the response is after the procedure. So I think it’s key to discuss this reality with patients when you talk about MIGS.”

What about recommending clear lens extraction to a glaucoma patient without a problematic cataract?

Dr. Samuelson says he almost never recommends a clear lens replacement to address slightly elevated pressure. “I don’t take someone who has no visual complaints and offer them cataract surgery plus MIGS,” he says. “I generally require a vision complaint, and the vision loss needs to be directly attributable to the cataract in most cases.

“That’s not to say they have to have severe symptoms,” he continues. “If they have a vision complaint and a cataract, and I think the complaint is related to the cataract, and they also need better control of their glaucoma, I’ll present cataract surgery plus MIGS as an option, especially if they have an unfavorable refractive error. I explain that the procedure can improve clarity of vision, improve pressure control, reduce medications and give them a more favorable refractive error. And it’s a procedure they’ll need at some point in their life anyway.

“If the benefits are substantial, proceeding with phaco-MIGS is simply moving something a little forward in the treatment scheme, and the idea is generally well-received,” he notes. “Of course, to take this approach, you have to mandate very low complication rates and high-quality surgery, but cataract surgery is so good these days that most of the time we can expect that.”

What about just offering cataract surgery without MIGS? “The only time I might offer cataract surgery without MIGS to a glaucoma patient is when the patient has compromised angles,” says Dr. Samuelson. “In that situation, just removing the cataract might be beneficial for their outflow. But most glaucoma patients can benefit from cataract surgery plus MIGS.”

Continuous Drug Delivery

Another recent addition to the glaucoma armamentarium is the sustained-release device Durysta that’s implanted inside the eye and releases a steady dose of bimatoprost. Using a prostaglandin as a first-line treatment is hardly a new idea, but this new format comes with several benefits and drawbacks—at least for now.

“I’m convinced that slow, sustained release is the future of glaucoma medical management,” says Dr. Khouri. “We’re all familiar with the obstacles to successful topical therapy: poor adherence; hand-eye coordination issues; arthritis; tremors; and poor aim, among others. These medications only work if they actually make it to the surface of the eye, and even when they do, they can cause ocular surface disease. I think a lot of the variability in IOP that we witness in glaucoma patients—which is definitely associated with progression—is due to patients not using their topical medications correctly. Slow-release drug delivery options could avoid all of these obstacles.”

“Typically, these devices provide six months of pressure-lowering,” notes Dr. Asrani. “Sometimes it’s nine months. But we’re talking about months, not years, and the sustained-delivery choice that we have at present is, unfortunately, not repeatable, per the FDA. Clearly more doctors would choose this option if it could be repeated. If a patient is controlled solely on a prostaglandin—and that’s a lot of patients—but doesn’t want the hassle of using drops every day, they could be better off with the prostaglandin released inside the eye rather than on the surface. These devices would not only remove the compliance concern, they’d reduce the amount of preservative getting onto the eye, and potential side effects associated with prostaglandins.

“Everyone anticipates that there will be even longer-lasting sustained-release delivery systems, or that the FDA might approve a repeat injection,” Dr. Asrani adds. “That could change the way we practice. But so far, we’re not there.”

“I think the sustained-release implant does have a role, but there are two significant limitations to offering it right now,” says Dr. Samuelson. “First, it’s been difficult to get payors to buy into the concept, so there’s an insurance barrier. Second, patients are receptive to the idea, but it’s a bit of a challenge to explain how it’s going to be beneficial in a chronic disease if it’s only approved for one-time use. Naturally, Allergan is working with the FDA to try to figure out how best to move toward being able to implant it more than once.

“We’ve been using it in patients with significant ocular surface disease who just don’t tolerate medical therapy, and those with compliance issues,” he continues. “However, some of those matters would also push us toward doing laser first, because that’s very well established in terms of payor reimbursement coverage. If your options come down to Durysta or SLT, it’s far more straightforward to do SLT than to go through all of the prior authorization gymnastics you have to do to get approval to use the bimatoprost implant.”

SR Options in the Pipeline

Dr. Asrani points out that other new variations on the sustained-release idea may hold promise as well. “Some that are in the works are intracameral, such as a drug-releasing iStent,” he says. “That would require surgery. It would be great if something similar to the bimatoprost-containing ring that sits on the eye underneath the eyelids gets approved; that’s something we can remove if it doesn’t work. We know some polymers can be formulated with medications and last longer than a month; we currently have a punctal plug for dry eye that takes six months to dissolve, called FormFit. Couldn’t a glaucoma drug be mixed with that polymer?”

Nevertheless, Dr. Panarelli says that he believes that for continuous drug delivery, an intracameral device makes the most sense. “That would seem to be the best option in terms of eliminating compliance and tolerability issues,” he notes. “Other platforms, such as punctal plugs that elute medications or ring inserts that do the same, have great potential benefit from a compliance standpoint. However, there are issues with retention and dislodgement of those devices.”

“An advantage of Durysta is that you can do the procedure right at the slit lamp,” Dr. Samuelson adds. “Some of the others—for example, the iDose from Glaukos—require a much more sterile OR-type setting. On the other hand, early reports suggest that the duration of response with the iDose might be long enough that this is palatable because you won’t have to go to the OR very often.”

Dr. Khouri notes that Durysta is just the first chapter in this book, and Dr. Panarelli agrees. “If a single implant could replace multiple medications and have a long-lasting effect—and maybe even help permanently enhance outflow facility—I think many ophthalmologists would implement that option early in their treatment algorithm. In the meantime, physicians and patients will continue to become more comfortable with the currently available options and, as this happens, we’ll get a better sense of how effective and safe these options are.”

Dr. Samuelson is a consultant for Alcon Surgical, Abbott Medical Optics, AqueSys/Allergan, Equinox, Glaukos, Ivantis, Bausch + Lomb, Aerie, Advantix, SightScience, New World Medical and iScience. Dr. Khouri has received grant support from Allergan, is a consultant for Glaukos, and is on the speakers bureau for Allergan, Aerie and Bausch + Lomb. Dr. Panarelli is a consultant to Santen, Allergan, CorneaGen, New World Medical, Glaukos and Aerie. Dr. Asrani reports no financial ties to any product discussed.