In recent years, glaucoma specialists have accumulated increasing evidence that a single measurement of intraocular pressure, which varies throughout the day, does not adequately reflect pressure's importance in the disease.

"We do not know what the significance of variation in IOP is at this time," explains William C. Stewart, MD. "For a long time in clinical trials only a morning trough and peak pressure was taken, then when the prostaglandins were evaluated in the early 90s, the [Food and Drug Administration] also asked for an afternoon time point. This gave rise to the three-point diurnal curve."

Dr. Stewart, a professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Carolina Eye Institute,

"We traditionally limited ourselves in our IOP evaluations of these new medications. Over time the question really arose about what was happening with regard to fluctuation the rest of the day," he says. "There is some evidence that fluctuations in general are important risk factor in progression, independent from the mean pressure, which has clearly been shown to be a risk factor for progression," he says.

While the precise impact of IOP fluctuation remains unknown, the variability certainly affects the clinician's ability to determine the efficacy of efforts to lower pressure, and even the ability to choose a target pressure. And while some fluctuation appears to be the norm, large swings can have deleterious effects in certain patient populations.

Sanjay Asrani

At-Risk Patients

Typically, IOP fluctuations are seen in patients with uncontrolled glaucomas. "These patients' visual fields are progressing," says Dr. Asrani. "When we look at their IOP, it is usually not stable. The more advanced the glaucoma is, the more significant fluctuation seems to be."

Dr. Stewart adds, "We do know that the higher the pressure, the greater the fluctuation. Patients with exfoliation typically have higher pressures, and their fluctuations are higher even after treatment. Of course, these patients progress more often so that could be related to the higher mean pressures, but it may be the high fluctuations as well."

Varied Results

Recent studies have produced varied results. "Our study published in the Journal of Ocular Pharmacology & Therapeutics showed in the retrospective five-year follow up that day-time fluctuation in pressures was an independent risk factor for progression," Dr. Stewart explains (See Figure 2).2 He added that a caveat with this study was that not all of the five-year retrospective trials showed fluctuation as an independent risk factor.

Studies such as AGIS looked at the estimation of peak pressures.3 "[AGIS] showed that if the peak pressure was no more than 18 mmHg combined with the mean pressure of 12.8 mmHg, few patients progressed over five years," says Dr. Stewart. He notes that the study, however, did not show that the peak pressure was an independent risk factor.

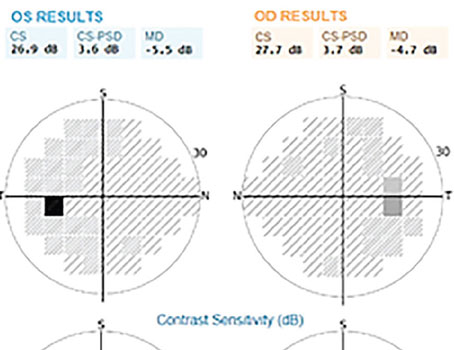

Dr. Asrani and his colleagues found that the range of pressure on the different days seems to correlate highly with progression.4 Therefore, fluctuations in IOP may be important in managing patients with glaucoma and development of methods to control fluctuations in IOP may be warranted (See Figure 1).

Checking Pressure

Clinicians can employ a few diagnostic options to attempt to discover the true nature and frequency of the fluctuation in IOP. However, the best method is also subject to debate.

Dr. Stewart suggests that the one thing clinicians can do right now is to do a modified diurnal curve. "Don't check the same time every day," he says. "Check it at different times of the day, throughout the day over time, and find a peak. That peak is probably the time it should be checked more often and used to gauge therapy."

Dr. Asrani also recommends that ophthalmologists have their patients vary their scheduled appointments through out the day. "You don't necessarily have to call them back frequently if their glaucoma is mild or they do not seem to be progressing; but at least spread out their regular visits so the variation can be determined," he says.

Another option is to request that patients come in for a "pressure check-only visit." These visits can be used for a data collection at different times of the day. "If a patient has advanced glaucoma and the clinician is worried that he is progressing, then it is often helpful to call the patient back over a span of three or four weeks at multiple times," Dr. Asrani says.

The options for conducting intra-day or inter-day fluctuation of pressure measurements are limited except for diurnal curves. "One can do mini-diurnal curves by having patients come in for a span of three to four hours for two non-consecutive days—rather than spending a whole day in the office. This span gives a snapshot into how the patient's pressures are changing," he advises.

For instance, one day the patient can have pressure checks at 9, 10 and 11 o'clock and on another day the pressure checks can be taken later in the day at 4, 5 and 6 o'clock. "This way for example, the clinician could observe if the pressures in the morning were 10 and 12 mmHg, and then in the evening they were 19 and 18 mmHg, in this eye there is a large range of pressure which seems to be a critical value," he says.

Other Diagnostic Options

There are two other options for trying to determine how high a patient's pressure is rising. Researchers have demonstrated that having the patient placed in the supine position is helpful to determine how high the pressure can rise.5,6

"In our studies we have demonstrated consistently that at least two-thirds of the patients have their highest pressure during the nocturnal period," says Robert N. Weinreb, MD, distinguished professor of ophthalmology and director of the

"If one does not have access to 24-hour measurement and wants to get a better understanding of peak IOP, the measurement that appears best to correlate with peak IOP is one obtained in the supine position during usual office hours," he says. Dr. Asrani agrees that having the patient lie down during a day visit and then checking the pressure could "give us the range of how high the pressure can rise."

Dr. Stewart points out that having patients lie down to take their pressure can be problematic in practice, because a change in measurement technique is required. "This might change the pressure, and also it takes extra time," he says. "The problem is that even though we know the pressure does go up when you lie down, we have not related supine pressures to outcomes. In one sense we don't know what to do with that information. We do know that a sitting pressure with Goldmann should be generally 18 mmHg or less," he says.

Supine pressure measurement can be helpful when the patient progresses for unknown reasons or if you have a suspected low-tension glaucoma patient. "This is the time to lay the pressure down and make sure the pressure is not going really high (as some of them will when you lay them down) and to rule that out," Dr. Stewart says.

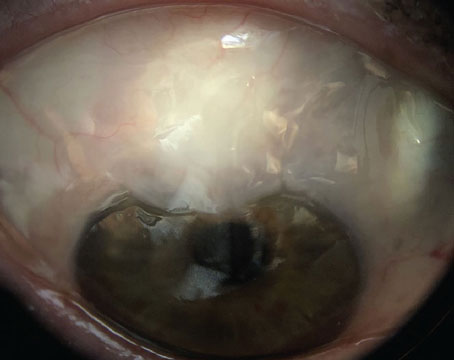

The water drinking test is another option. (Experts disagree on its validity.) After checking to make sure there are no contraindications to fluid overload, patients are asked to drink a liter of water and then have their pressure checked every 15 minutes for three times. This method, employed by Dr. Remo Susanna,7,8 is helpful to determine if the pressure increased by more than 5 mmHg. "If so, we assume that there is an obstruction of the outflow system," Dr. Asrani says.

Medical Options

The more advanced the glaucoma, the more narrow the range of variation/fluctuation should be. "Long-acting drugs are better in controlling fluctuation, such as all prostaglandins and Cosopt," Dr. Asrani says. "The range with these eye drops is within the range of a normal eye fluctuation." He notes that a combination of eye drops also could be used to attempt to control the fluctuations.

Dr. Stewart agrees. "Prostaglandins absolutely are the best class that we know about for fluctuations based on Professor Konstas's and my findings. We found the level of fluctuation to be the best with Travatan [3.2 mmHg], and then Lumigan [3.5 mmHg]. We had the most experience with Xalatan [range 3.8 to 4.4 mmHg]," he says (See Figures 3 and 4).

Other medications also have been proven to reduce fluctuation. "We found over a number of studies that the average non-treated 24-hour fluctuation is 7 mmHg," Dr. Stewart says. "Timolol tends to be the best non-prostaglandin in reducing fluctuations because it has 24-hour action, and it has fluctuations of about 5 mmHg. Alphagan and Trusopt tend to have higher fluctuations, above 5 mmHg."

"Fixed-combination therapy with Cosopt does further reduce fluctuations, but about to the level of a prostaglandin as an individual medicine. The prostaglandins would be the first-line therapy in terms of mean reduction of pressure fluctuations. They tend to do the best in terms of IOP efficacy for those two parameters," Dr. Stewart explains.

Surgical Options

Dr. Stewart says there is too much unknown about fluctuation for it to be a factor in considering glaucoma surgery. "I would not consider surgical options based on fluctuation. We just don't know that much about it," Dr. Stewart says. A recent study from Dr. Stewart and Professor Konstas showed that a successful trabeculectomy would reduce the fluctuations to about 2.3 mmHg.9

"It sounds good, but we just don't know yet if that is clinically important. The clinical significance needs to be explored and we are not saying you need to do surgery first," he says.

Dr. Asrani concurs that if medication or combinations of medications do not help then ultimately surgery is an option. "A well-done surgery, like a trabeculectomy that is functioning very well, not only keeps the pressure down, but it keeps the pressure very stable. Therefore, typically trabeculectomy is the treatment of last resort because it does work," he says. "In the long term, our clinical experience has shown us that well-functioning trabeculectomies do keep visual fields stable over the long run," he says.

Future Outlook

While current monitoring systems provide a snapshot of IOP fluctuation and variation, more data are needed to better understand the whole picture of this complicated subject.

Dr. Weinreb says, "In the future, we need and hope for a continuous 24-hour monitor of intraocular pressure because it changes not only hour-to-hour or minute-to-minute. IOP is changing instantaneously in everybody at all times. The best means for us to understand the relationship between IOP and glaucoma would be to have something that captures IOP continuously," he says.

Continued research may answer some of the remaining questions, says Dr. Weinreb. For example, he and his colleagues measure IOP in the habitual positions (sitting during the day and supine during the nocturnal period) to best mimic what happens in most individuals who are sitting or standing during the day and supine while they sleep. In a supine position, IOP is always higher than in a sitting position, he says.

"However, if one even looks at variation of IOP over 24 hours when obtained only in the supine position, peak IOP still most often occurs during the nocturnal period. So there is something more than just the supine position that accounts for the peak pressure," Dr. Weinreb explains. "We still don't know why IOP pressure is highest during the night-time period. It may be related to changes in the autonomic nervous system," he adds.

1. Fluctuation of IOP and Glaucoma Progression in the EMGT. Bengston, Leske C, Hyman L, Heijl A. Ophthalmology 2007;114:205-209.

2. Stewart WC, Day DG, Jenkins JN, Passmore CL, Stewart JA. Mean intraocular pressure and progression based on corneal thickness in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2006 Feb;22(1):26-33.

3. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:429-40.

4. Asrani S, Zeimer R, Wilensky J, Gieser D, Vitale S, Lindenmuth K. Large diurnal fluctuations in intraocular pressure are an independent risk factor in patients with glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2000;9:134-42.

5. Mosaed S, Liu JHK, Weinreb RN. Correlation between office and peak nocturnal intraocular pressures in healthy subjects and glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:320-324.

6. Liu JHK, Bouligny RP, Kripke DF, Weinreb RN. Nocturnal elevation of intraocular pressure is detectable in the sitting position. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44: 4439-4442.

7. Susanna R Jr, Hatanaka M, Vessani RM, Pinheiro A, Morita C., Correlation of asymmetric glaucomatous visual field damage and water-drinking test response. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:641-4.

8. Susanna, R. Jr, R M Vessani, L Sakata, L C Zacarias and M Hatanaka. The relation between intraocular pressure peak in the water drinking test and visual field progression in glaucoma. Brit J of Ophthalmol 2005;89:1298-1301.

9. Konstas AG, Topouzis F, Leliopoulou O, Pappas T, Georgiadis N, Jenkins JN, Stewart WC. 24-hour intraocular pressure control with maximum medical therapy compared with surgery in patients with advanced open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2006 May;113:761-5.