|

| With the proper approach, lenses can often be easily cut and removed through the original surgical incision, as long as the surgeon performs the explantation soon after surgery. |

Before the advent of premium intraocular lenses, and when LASIK patients weren’t yet old enough to develop cataracts, an IOL explantation was a rare bird. Now we see flocks of them in our offices, mainly due to two factors: New lens technology that holds out the hope of a glasses-free life has made some patients more demanding in terms of their visual results; and the effect of LASIK on the cornea has made it more challenging to formulate spot-on IOL calculations. In this surgical environment, ophthalmologists have to be comfortable with doing IOL explantations and exchanges, even though they’re not always easy.

In this article, I’ll review the considerations involved with doing lens exchanges and share tips and techniques for doing them effectively.

The Reasons for an Exchange

In years past, we’d only perform an IOL explantation was for a lens that had been poorly placed during surgery or, more commonly, for someone who had undergone uneventful cataract surgery 20 years previously and whose lens had decentered due to the progression of pseudoexfoliation. Now, however, new conditions have emerged that make lens exchanges more common than ever.

• Postop LASIK patients. The patient with a history of LASIK throws off our lens formulas, and, even though we’ve been dealing with post-refractive patients for a while, we’re still trying to fine-tune our calculations. Even when taking many variables into account, we can end up with drastic power misses in these patients, especially when we can’t obtain their previous records. What’s more, even if we’re not very far off in our calculations—such as only 1 or 2 D off—these demanding patients still have that refractive-surgery mentality that prompts them to say, “I had surgery to avoid wearing glasses, so why are you telling me I have to wear them now?”

• Premium lens patients. Then there are the multifocal and accommodative IOL patients, who have paid substantial amounts of money to achieve distance and near correction. Their priority is achieving the correct IOL power for emmetropia, and we’ve developed new A-scan techniques and devices such as the IOLMaster and the Lenstar to help us do this. But it’s not always enough to avoid an error. In the world of premium lenses, being a hair off with the lens power is unacceptable; no matter how many times you warn patients about possibly having to wear glasses postop, if they actually have to wear glasses, you’ll have a disappointed patient.

• The unhappy premium patient. Another indication is the multifocal IOL patient whose refraction is good but who is simply unsatisfied. You might have a multifocal lens patient who, after two weeks with the lens, is complaining of image halos and generally poor quality vision. This person isn’t going to be happy despite your best efforts. At this point, you’re obligated to save yourself a lot of aggravation and begin the discussion of explanting the lens and replacing it with a monofocal IOL. You have to recognize that, even though multifocal lens technology is great, not everyone is going to adapt to it.

• Anteriorly flexed Crystalens. Also, the advent of accommodative IOLs, mainly the Crystalens in the United States, introduced yet another possible scenario for explantation. Because the Crystalens is so flexible, it’s possible for it to go into an anterior flexed position that leaves the patient 1.5 D myopic. Fortunately, if this is going to occur, it happens pretty soon postoperatively. This needs to be addressed quickly, since the Crystalens’ design makes it very difficult to remove after four weeks, as I’ll discuss in the following section on explantation technique.

For patients whose refraction is off, some surgeons might advocate doing refractive surgery. Refractive procedures in these patients, however, aren’t a slam dunk; doing a touch-up PRK on someone with a 16-cut RK isn’t easy, and doing a surface procedure on LASIK corneas increases the risk for haze, glare and all the issues attendant with surface ablation. Plus, you can’t do any postop refractive surgery enhancement until at least three or four months post-cataract surgery. In many ways then, it’s easier to do a lens exchange, as long as astigmatism isn’t the main reason for the IOL miss.

It’s also important to stress that, for patients with visual complaints about their multifocal IOLs in the early postop period, you should not perform a YAG capsulotomy right away. Should you have to do a lens exchange later, a history of posterior capsulotomy transforms a relatively straightforward IOL exchange into an IOL exchange and a vitrectomy. The latter surgery is much higher risk, much longer and much more complex. So, in most cases in which someone has complaints that aren’t mild, it’s best to address these complaints early and not wait three or four months. Of course, if the complaints are mild, you can wait, but there are some cases where the lens simply has to come out, and it’s much easier to do that before you’ve created an opening to the posterior segment with a YAG capsulotomy.

Technique Tips

Following are thoughts on how to approach various common explantation scenarios:

• Routine removal of a one-piece lens at four to six weeks. In terms of timing the explantation, you have a good, solid four weeks—possibly as long as six—during which you can easily viscodissect open the capsule and, with a little finesse, rotate the lens to get it out of the bag. Here’s how we do it.

We bring the patient back into the OR and administer a nerve block, even if we didn’t use one for the initial cataract procedure. The reason for this is that since you’re going to be doing a lot of manipulations of the iris, you don’t want the patient to be in pain and squeezing his eye frequently. Even though you may have projected an air of “It’s easy as one, two, three, we’ll just switch your lens,” you need to have the patient completely comfortable for the operation.

Next, you don’t need to make another clear corneal incision. Instead, you can just refresh your existing corneal wound with a 30-ga. cannula with BSS on it, rubbing up and back on the incision. However, don’t go back through the original wound with a blade. If you do, you’ll create multiple layers in the incision and can get tearing in Descemet’s. If you can’t blunt-dissect the original wound with the 30-ga. cannula, move right next to it and create a new keratome wound.

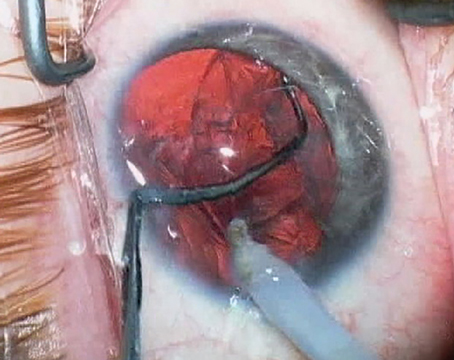

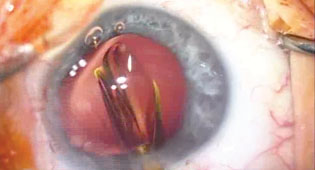

|

| A relatively thin viscoelastic above and below the old lens gently breaks the lens adhesions and inflates the capsular bag. |

Once the adhesions have been broken, you can gradually lift or rotate the lens out of the capsular bag without disinserting the zonules. Then, with the lens out of the bag, you sandwich it with viscoelastic on the top and bottom and bring in the lens cutter. With the help of a Kuglen lens manipulator (ASICO) or the Grayson manipulator (Storz/Bausch + Lomb)—it has smooth edges to avoid doing damage to ocular structures—you use the lens cutter to divide the lens in half. (I have no financial interest in the manipulator.) You can then pull out the halves through the main incision. You should also have a nice inflated bag for insertion of the new lens.

If there’s any sign of instability during the explantation, I place iris retractor clips and clip the edge of the anterior capsulorhexis. This gives support while also stretching the anterior capsule open to give me some more room to work.

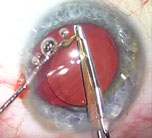

|

| Use a second instrument, such as a Kuglen manipulator, to help steady the old lens as you cut it. |

Therefore, it’s actually good to plan ahead when implanting a Crystalens. When you implant one, it’s best to put it in vertically at 90 degrees, because your cataract wound is at 180 degrees. If you were to orient the lens horizontally at 180 and you needed to explant it later, you’d never be able to get a scissors through the existing wound to cut the haptic opposite you. However, if you put the lens in at 90 degrees, you’ll have good access to the two hinges through your original wound.

In some cases, though, if the patient’s old lens is a three-piece IOL with thin haptics, you may be able to rotate it out, because the smooth haptic can sometimes slide right out of its groove. However, for Alcon and AMO one-piece lenses, the edges of the haptics flare out and embed themselves in the bag. If you try to pull any of these kinds of lenses out, you’ll dehisce the zonules and ruin your chances of putting in another lens.

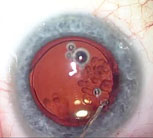

|

| Once all capsular adhesions have been carefully cleared with viscoelastic and the old lens removed, the surgeon can easily expand the capsular bag and insert a replacement intraocular lens. |

If you have to leave the haptics in the eye, you’ll have to place a sulcus lens. In my opinion, the current best sulcus lens is the Staar AQ. It’s a long lens and sits very well in the sulcus. In the absence of an AQ, any three-piece acrylic, such as the Alcon AcrySof and the AMO Tecnis, are acceptable options for sulcus placement.

Also, some old lenses only get their support through posterior iris synechiae, and have no zonular support left. You won’t discover this until you’re in the eye removing the old lens. Be prepared for this by always having anterior chamber IOLs ready.

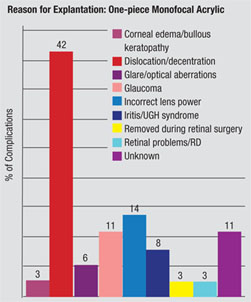

| Survey Reveals the Main Reasons for Explants | |

Every year, Nick Mamalis, MD, and his colleagues at the University of Utah’s Moran Eye Center conduct a survey of members of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery and the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery in which they ask surgeons about complications with foldable intraocular lenses that led to explantation. Here, Dr. Mamalis discusses aspects of the most recent survey.

Every year, Nick Mamalis, MD, and his colleagues at the University of Utah’s Moran Eye Center conduct a survey of members of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery and the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery in which they ask surgeons about complications with foldable intraocular lenses that led to explantation. Here, Dr. Mamalis discusses aspects of the most recent survey.

For monofocal lenses, the main reason for explantation was dislocation/decentration. “We have met the enemy and he is us,” says Dr. Mamalis. “Unfortunately, we can’t blame the IOLs for causing the problems with decentrations/dislocations. It’s mainly the surgical technique, though some patients may have had loose zonules.” The survey’s surgeons proffer some advice for decreasing this complication. “The most important step in ensuring that a lens isn’t dislocated is that you have a well-centered, well-sized capsulorhexis,” says Dr. Mamalis. “Because if you start with a good capsulorhexis, and don’t have anything that could disrupt the capsule such as a capsular tear, then the chance of dislocation is very small. But if you have a capsulorhexis that’s irregular, too big or extends in any way, the risk for dislocation goes up.” The survey is also starting to amass data on multifocal and accommodating lenses. “What’s interesting is that if you look at the data from multifocal lenses, more are being explanted primarily for glare/visual aberrations, a complication that’s not showing up in monofocal lens types,” says Dr. Mamalis. “These lenses are definitely different, so proper patient selection and counseling are critical if you’re going to use them.” Glare and optical aberrations were also the number one reason for explantations of the Crystalens in the survey. “However, we just added the Crystalens to the survey and only had a handful of those lenses submitted to us, so we have to be careful about drawing any conclusions about it.” As for future surveys, Dr. Mamalis says the next trends may come from the patient side of the equation. “I’m interested to see what happens when baby boomers who have had RK and LASIK start undergoing cataract surgery,” he says. “I’d like to see if we start getting more refractive errors post-cataract surgery.” —Walter Bethke |

Alternately, you can place an infusion cannula in the peripheral clear cornea and a port in the pars plana and do the vitrectomy that way. Since the patient’s had a posterior capsulotomy, you have an open communication within the entire globe, so you don’t necessarily have to place an infusion port via trocar in the pars plana.

The best sequence for this procedure is as follows: Put in the trocars while the globe is well-formed; cap off the infusion port; do all of your anterior segment manipulation in preparation for the lens explantation; remove the old lens; go back and do your vitrectomy; and finally place the new lens in the sulcus. If you take the lens out first, the eye will be too soft to get the trocars in the right spot.

• Removing an old PMMA lens. Surgeons can sometimes be surprised by a PMMA lens, since such a lens can’t be cut and needs to be explanted whole. In such cases, you may want to use a scleral tunnel wound at least 6 mm wide. The scleral wound gives a little more self-sealing stability. Also, for these cases I probably wouldn’t plan on putting the replacement lens in the sulcus, because the odds are you’ll just have to take it out and ultimately put in an anterior chamber lens using a 6-mm wound.

Placing an AC IOL

Sometimes, you won’t be able to place an IOL in the sulcus following an explantation and instead you’ll have to fixate one in the anterior chamber. Here are some tips for the best results.

I use a 6-mm scleral tunnel for the procedure, and I’m also prepared to perform a vitrectomy, since patients who had their original cataract surgery years ago and are now aphakic will need a vitrectomy for sure. Again, if I have to perform a vitrectomy, I make sure my trocars are in before the eye is opened in order to make it easy to place them.

An iridectomy is a must in these patients, since these AC lens patients will almost always develop pupillary block. Also, remember that it’s always easier to make an iridectomy before you place the new lens. In my cases, I always make one first.

I then put in Miochol and Myostat, instill viscoelastic and place the lens, rotating it a little to make sure its sizing is accurate. If the lens is too small, which you’ll know if it’s freely spinning in the anterior chamber, you’ll need a larger one. However, be careful: Jamming a lens that’s too big into the chamber is just as bad as using a small lens, because the large lens has a greater potential for compressing the angle and causing chronic cystoid macular edema and inflammation. With the correct lens in place, I close the case with two or three 10-0 nylon sutures.

I don’t find pre-existing glaucoma to be a contraindication to implanting an AC lens, even though there’s a school of thought that recommends a posterior chamber lens for these patients. I’m not sure whether an AC lens causes that much more potential for glaucoma, but if the patient’s on multiple medications, an AC lens implantation allows me to perform a small trabeculectomy at the same time as the lens exchange. The trabeculectomy is very easy to do because I’ve already made a scleral flap to insert the AC lens. It’s almost like doing a combined cataract/trabeculectomy, except I’m not doing a cataract, just converting the flap for use with the trabeculectomy. When I’m finished, I have a nice trabeculectomy in combination with an AC lens and some outflow protection.

Though lens explantations can be tricky and need to be done with some finesse, they are increasingly necessary. If you have plans for a full-service cataract practice you have to be ready, both mentally and in terms of your surgical skills, to perform lens exchanges.

Dr. Grayson is an attending surgeon at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital and Lenox Hill Hospital.