|

| Smartphone technology is helping to make eye examinations more portable. Above: the Paxos Scope (DigiSight Technologies), a universal smartphone adapter that allows doctors to capture high-resolution anterior and posterior images of the eye. |

“Patients are partners in their care now more than they were 10 years ago,” says Richard M. Awdeh, MD, assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology and assistant professor of ophthalmology and pathology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. (Dr. Awdeh is the creator of the CheckedUp platform, an educational platform created to facilitate the doctor-patient relationship.) “Ten years ago patients would go to the doctor, the doctor would tell them XYZ, then they’d walk out and that would be it. Today, patients want to be more engaged. They want to be a part of the decision-making process; they want to be informed; they want to understand why decisions are being made. As a result, they’re now more actively involved in their care and taking more ownership of their care. I think that’s a big change, and I think we’ll continue to see more of it.”

Here several health-care professionals who are caught up in these changes discuss what they see happening and where all of this may be leading.

Patient Self-assessment

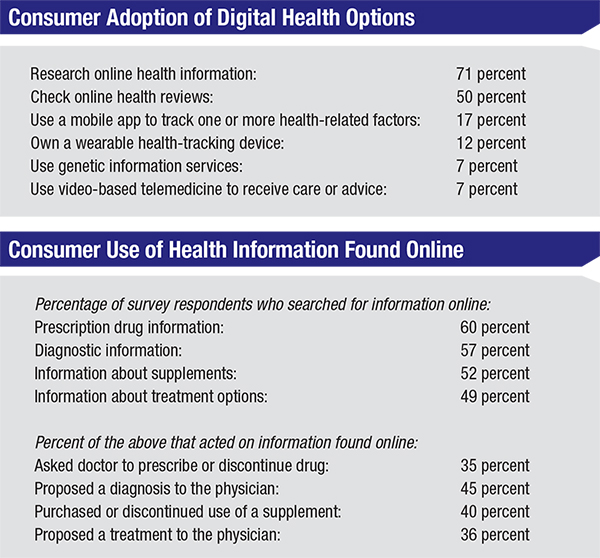

As most physicians are well aware, today’s patients are tempted to self-diagnose because of their access to copious amounts of medical information on the Internet. “As a July 2015 Rock Health survey of 4,017 respondents with mobile Internet access showed, the most popular digital health adoption was accessing online health information sites such as WebMD, which 71 percent had done,” says Robert T. Chang, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif. (Dr. Chang is co-developer of the EyeGo adapter, licensed to Digisight Technologies as the Paxos Scope, which facilitates the capture of high-quality photos of the front and back of the eye using a smartphone.) “Fifty percent indicated historical use of online reviews, but only 17 percent engaged in mobile health tracking, which is often cited as having a steep drop-off after six months. Despite the hype and promise, video-based telemedicine usage was only 7 percent. (See tables, right.)

“An increasing number of eye patients in Palo Alto come to Stanford asking about the latest cataract surgery technologies,” he continues. “The rapid dissemination of new medical information via the Internet has encouraged the ‘democratization of health care.’ However, patient online research sometimes leads patients to believe they know more than they do, or induces more anxiety. The problem with reading articles on a site like WebMD is that you may learn something about the condition, but it won’t necessarily help you understand the unique aspects of your own condition.”

|

| Today, multiple companies are participating in the shift toward digital health care. Their offerings can be divided into six overarching categories: online information; reviews of practitioners; mobile fitness-tracking services; wearable tracking devices; consumer-oriented genetic services; and telemedicine. The data above came from a survey of 4,017 consumers done by Rock Health, a venture fund dedicated to digital health. (For more survey results, visit http://rockhealth.com/reports/digital-health-consumer-adoption-2015/.) |

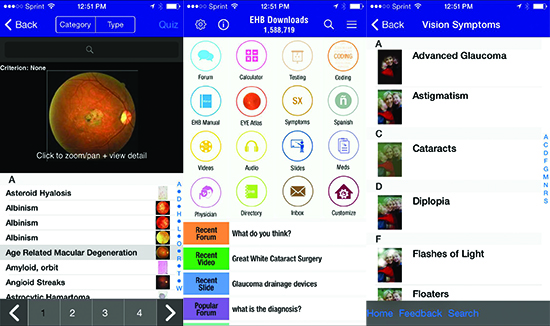

Ken Lord, MD, a vitreoretinal specialist at Retina Associates of Southern Utah, is the co-developer of The Eye Handbook. (The Eye Handbook is a diagnostic and treatment reference application for eye-care professionals; it’s the number-one mobile ophthalmology app, downloaded more than 1.5 million times to date.) Dr. Lord agrees that self-assessment is a trend. “There’s a lot of this kind of thing going on,” he says. “We don’t want to assume any liability as a result of putting something out there that allows patients to test themselves, so we have to be careful. However, patients are going to do whatever they want to do.

“The Eye Handbook app is not designed for patients, so there’s no specific patient-use area, but patients are occasionally using it,” he continues. “There’s a section that allows you to test your vision with a near card and do some color vision tests, although obviously this doesn’t replace office-based testing. You can also look up what symptoms of certain conditions might feel like or look like; that’s popular with patients. (See examples on p.32.) The Eye Handbook doesn’t have much competition as a comprehensive eye-care application, but there are at least 100 apps that test color vision and near vision and do other types of vision testing, available on both of the app stores.

“Apps have even been developed to determine a patient’s refractive state, along with programs on the computer that allow a person to determine the glasses or contact lenses he needs and order them,” he continues. “So far, none of this has been approved by the FDA; you still need a prescription from a doctor to order glasses or contact lenses. But it’s becoming a lot more common for patients to try to do a self-assessment. We’re living in that kind of do-it-yourself culture. People feel empowered because of current technology, being able to Google medical conditions and treatments. That’s definitely the trend.

“I doubt that self-testing will replace the instruments and methodology you find in a real clinic,” he adds. “Plus, a lot of people want a complete professional analysis by a physician. But there’s a certain segment of our culture that’s probably going to use that technology.”

Problems with Self-testing

While self-testing is an appealing concept, a number of issues may prevent it from becoming a mainstream medical tool any time soon.

• Questionable accuracy. Can consumer self-testing be accurate? “Theoretically, yes,” says Dr. Lord. “A team at MIT is developing an app and smartphone device that should be able to determine what the refractive state of the eye is; they hope to market it within four years. The user will look through a series of lenses and projections in the device. There are similar programs in development that don’t even need a device attached to the smartphone. Their accuracy remains to be seen.”

• Lack of validation. Simply being an accurate test isn’t enough. “Many apps allow you to test your vision on your smartphone at home—a low-hanging-fruit medical test,” notes Dr. Chang. “The problem is that there is no oversight to ensure quality control of data collection, and home testing is just starting to be validated against gold standards. If physicians are going to make a medical decision based on a consumer digital device measurement, they want to see FDA medical-grade validation.”

• It’s only one measurement. Dr. Chang points out that self-testing doesn’t constitute a full exam. For many medical decisions the doctor needs multiple pieces of information that may be impossible to collect at home. “For example, it’s difficult to think of a situation where visual acuity alone would be to make a medical decision,” he says. “It’s like a vital sign; we still need other diagnostic information to conclude what’s going on with the vision change. However, if we were to start combining multiple pieces of information such as visual acuity and refraction measured by a tool like the Smart Vision Labs SVOne, with eye pressure measured by a tool like I-Care Home, and smartphone photos of the front and back of the eye, plus a portable OCT of the retina, then remote telehealth might be more readily accepted by practitioners. Until then, remote testing is more like remote triage—it primarily helps determine the level of urgency or severity of the problem.”

• It may not be actionable information. Another problem with current consumer health monitoring technology is that it often provides data that is not actionable yet—even if it were validated. “A device like the Fitbit can monitor your heart rate all day, but what is the actionable information?” asks Dr. Chang. “Most people who care enough to monitor their exercise probably don’t need the device to help them to exercise more; it simply appeals to their quantitative side. Right now, we have a data collection problem since we don’t know what to do with all the big data coming from daily monitoring. The hope is that some new insights will arise from all the shared data in the future, but machine-learning research will be needed to sort it all out.”

Dr. Chang acknowledges that some of today’s digital monitoring is, in fact, actionable. “Real-time blood glucose level monitoring in some individuals is actionable because you may need to give medicine directly related to an individual value; too high or too low a value might have dire consequences,” he says. “Thus, those situations are where digital health will first make a difference. Another example of digital therapeutics having a sustained impact is Omada Health, the first digital-health start-up to have published positive two-year results demonstrating that their Internet program helped participants maintain clinically meaningful reductions in weight and hemoglobin A1c. Whether something like that will apply to eye care, such as chronic glaucoma therapy compliance, remains to be seen.”

Dr. Chang does point out that non-actionable data from large numbers of people in a population might be useful in other ways. “It helps with population-based data analysis,” he says. “For example, thanks to these digital health apps, researchers have gathered unprecedented amounts of activity data from tens of thousands of individuals in a very short amount of time from the MyHeartCounts app. That kind of information may allow us to make better public-health decisions.”

Despite the limitations of self-testing, Dr. Chang does sees potential in it. “At some point in the future, it may be possible to prescribe home monitoring that will catch the earliest signs of a problem, before the patient can tell something is abnormal,” says Dr. Chang. “That device will be more useful as a remote measurement tool. Today there is one FDA-approved home-monitoring vision test: The ForeseeHome AMD Monitoring Program from Notal Vision. It helps patients detect central and paracentral metamorphopsia as an aid in monitoring progression of the disease. But it still must be prescribed by a physician. In the meantime, a lot of information from consumer devices falls into the category of new data that we don’t know what to do with yet, since it’s never been collected in this manner. However, companies and researchers are eager to find the added value and sensitivity/specificity levels of new diagnostics.

“At the same time,” he adds, “having an app quantify exactly how much vision loss you’re experiencing may be unnecessary if your vision is already bad enough to make you want to see a doctor directly.”

Digital Communication

With a handy communication device in most people’s pocket, doctors and patients are able to reach each other (or at least leave a message) at almost any time or place.

|

| Above: Sample screens from The Eye Handbook app (created by Cloud Nine Development), a popular free diagnostic and treatment reference for eye-care professionals. Although the app was not intended for patients, sections that explain what different conditions look or feel like (above, right), as well as some basic near and color vision tests, have become popular with many patients. |

Digital communication, of course, is a two-way street; in addition to making it easier for patients to contact their doctors, it also makes it easier for doctors to reach patients with important information relevant to their condition and treatment. However, Mark M. Prussian, MBA, FACHE, chief executive officer at The Eye Care Institute in Louisville, Ky., notes that having a digital channel to communicate doesn’t always result in communication. “The Eye Care Institute sends out patient information sheets through the practice’s EHR system, to educate patients and to comply with Meaningful Use requirements,” he says. “Unfortunately, our anecdotal evidence indicates that the patients often don’t read what we send.

“We continue to have amazingly strong success with our e-newsletter, which is now more than 10 years old, but this is a one-way push of information from us,” he continues. “We know it’s successful because with each newsletter we get between 50 and 100 responses asking for everything from more information on the topics we covered in the newsletter to how much is the patient’s balance due. In addition, we’ve used a patient portal for more than six years; we encourage our patients to ask us clinically relevant questions using the portal. We’ve found that very few patients use the portal, and those who do often ask about their balance due or their next appointment time. There aren’t many interactions where the patient’s medical care or vision outcome is enriched by having the portal.”

Of course, one Internet resource is now used by nearly every doctor: a practice website. “All the doctors we work with ask us what’s important to have on their website,” says Dr. Awdeh. “I’d say there are two ways practices go when setting up their websites. Most use their website for three things: search engine optimization, to ensure that when a patient searches for a doctor in that area their practice comes up; providing patients with a way to make an appointment; and providing directions to the office. Some practices make their websites more complex, adding a blog and basic patient education, such as descriptions of diseases, but making a complex website can be challenging. It’s hard for one practice to build the type of website you’d be able to create if you were doing it in concert with hundreds of other practices. And it’s not clear how much a more complex website pays off.”

Digital Patient Education

A number of innovators are working to take better advantage of the potential of digital communication. Dr. Awdeh says his creation, the CheckedUp digital platform, helps practices keep pace with today’s technology. “CheckedUp is designed to take advantage of all the types of technology we’re accustomed to using in our everyday lives,” he says. “I created it because of the contrast I saw between our day-to-day use of technology outside the office and what was happening in the clinic, where I was explaining things to patients and then either having them watch a DVD or handing out a photocopy brochure.

|

| The CheckedUp platform allows patients to access information relevant to their specific medical situation, chosen by the physican, at any time or location through a secure HIPAA-compliant portal. The platform also includes information stations placed in the practice (example above). |

“This problem is compounded by all the new options we have to discuss with patients,” he notes. “When we’re talking to a new cataract patient we have to discuss different surgical techniques and implant options. Ten years ago we just had monofocal lenses; now we have torics, multifocals and accommodating lenses. Looking at presbyopia, we used to have nothing to offer. In the next few years we’re going to have several options for addressing presbyopia, from corneal inlays to presbyopia-correcting IOLs, to pharmacologic solutions. So the conversation we have to have with the patient has become fairly complex, and we need to have it in a shorter amount of time, under the umbrella of the patient wanting to understand it and be a partner in his care.

“My patients were asking the same questions over and over again and having trouble retaining things they were told in the clinic,” he continues. “I decided that there had to be a better way to manage this, one that would allow patients to re-access that information and let them revisit things we discussed in the clinic whenever and wherever they wanted. The reality is that patients who are better educated are more engaged in their care and have better adherence to the things that we ask them to do before and after a procedure. They are much more comfortable with their diagnosis and they play a more active role in the care program that we put together for them.

“Ideally, patient education can happen before, during and after the office visit,” he says. “It can also happen before or after going to the surgical center, or following a treatment when it’s necessary for the patient to continue to be adherent. We’ve designed CheckedUp to facilitate patient education in all of those situations. It gives patients the details that a health-care provider would provide for their specific procedure or diagnosis. The patient portal allows patients to ask questions and find answers, engaging the patient in a way that reading a brochure or watching a DVD does not. CheckedUp also includes a follow-up component; it provides data metrics to the practice showing how it’s doing at engaging and educating patients and how adherent their patients are. There’s also a follow-up program geared to each individual patient based on the patient’s education and adherence to the plan.”

Dr. Awdeh notes that the information patients access through CheckedUp is significantly different from what they may learn from surfing medical sites on the Web. “The CheckedUp platform is customized to each doctor and tailored to every patient’s specific care plan,” he says. “The patient may find information online that’s broad or universal, but the goal here is to provide information customized by the patient’s doctor and tailored to that patient, based on the patient’s specific diagnosis or condition. The feedback data provided to participating practices also allows our team to keep improving the educational material accessed by patients. We can see whether patients are responsive to certain types of education or not, and we’re able to change the information and presentation based on how patients interact with it. The CheckedUp platform also includes stations that are placed in the clinics.” (See example, above, left.)

Dr. Awdeh says that specific content and instructions from the treating physician are loaded into the platform through a practice portal and made available to patients through a patient portal, as well as at the clinic stations. “The portal gives each patient unique access, based on their current treatment,” he notes. “We’ve invested in a technology stack that includes best-in-class HIPAA security and data encryption. And of course, we want to make sure that doctors and patients have a very good experience when using it.”

Digital Strategies

To make the most of this shifting landscape, Dr. Lord suggests taking a few basic steps:

• Check for helpful apps. “In addition to publishing the Eye Handbook app, we’ve created a number of apps designed to help patients manage their connection to your practice,” he says. “For example, there’s an app that the patient can keep on her phone that lets her contact you, and there are apps that help patients track their medications or review their patient profile. These apps are intended to serve as a complement or companion to your website.”

• Make sure your website is mobile-friendly. “Having a website is key, but it has to be mobile-friendly,” says Dr. Lord. “Survey data is showing a clear trend: Patients are spending less time on their home computer and more time on their mobile devices—even when they’re at home. It’s easier to be on your phone than on your computer. Most of my patients are over 70, but they are pretty tech-savvy.”

• Make sure your practice is registered on the major search engines and doctor-review sites. “There are currently five or six well-known Internet sites at which patients write reviews of doctors and practices, such as Healthgrades,” he notes. “You want your practice to be seen on these sites. And you have to have your business up on the major search engines—certainly Google and Yahoo. They have business app portals; if you want to show up near the top of the list on their search engines, you have to be registered with them. Being visible on these sites and search engines is key for any successful practice in today’s market. That’s where people are searching for eye care.

| The Landscape Keeps Shifting |

| In addition to changing the ways in which information is captured and shared, evolving technology is also leading to a number of new options that are making patient care easier to access: • Seeing a doctor on the Web. Having a virtual consultation with a doctor over the Internet is a growing trend. “Companies such as Healthtap are offering to connect patients with a doctor via the Internet,” says Ken Lord, MD, a vitreoretinal specialist at Retina Associates of Southern Utah. “The patient doesn’t even have to go to an office. The patient can just register with the website and pay a fee—some of them do it for free initially—and ask the doctor a question, via text or video chat. Doctors can participate by registering at the website. Doctors make less money than they would seeing patients in the office, but for the right practitioner it might be an attractive option. You can work from home or the beach or the airport, answer a few medical questions and get paid. The idea of a virtual consultation is becoming more popular and probably will continue to do so.” Such a consultation would clearly not allow a detailed eye exam, but might allow an ophthalmologist to act as an advisor when a patient has a concern. • Taking the refractive exam to the patient. Another way in which the digital revolution is impacting medical care is by making some processes portable that previously were not. “For example, New York City start-up Blink is providing an on-demand refractive eye exam service,” says Robert T. Chang, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif. “A customer orders an eye exam online and a technician arrives at the consumer’s home or office with portable, smartphone-based refractive equipment called Eyenetra, developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab. The Eyenetra devices collect the information needed to prescribe glasses; that information is confirmed by an optometrist who emails the consumer a prescription for glasses within 24 hours. (You can find out more at goblink.co.) This is part of the online-to-offline business model for metropolitan areas.” • Live remote translation services. “Working in an academic university medical center, we are lucky to have access to live webcam translators,” says Dr. Chang. “The outsourced translation services were never that good, and now our full-time employed translators can use technology so they don’t have to travel around the hospital as much. While Google Translate has also markedly improved, the machine learning algorithm still has trouble with sentences and complicated medical explanations; thus, I still find it most useful for simple commands.” —CK |

• Keep in mind that having a practice website may not be sufficient. “It’s clear that you can’t just put up your shingle on Main Street and expect to do well today; but having a website, by itself, isn’t sufficient either,” says Dr. Lord. “Some practices will definitely benefit from a presence on social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Yes, you need to have a good, mobile-friendly webpage, but you should have a lot more. Your web page should only be 25 percent of your Internet presence.” (For more on this, see “The Dos and Don’ts of Social Media” on p. 25.)

• If you’re not tech-savvy, get help. “Many doctors, like me, are very tech-savvy,” says Dr. Lord. “I read up on this subject to stay current. But if you’re not inclined to focus on this, consider getting help. There may be someone on your staff who would be really good at managing this type of thing; I have people in my office who help me keep up. If you feel you could benefit from outside help, there are a number of consulting firms out there that will do all of this for you.”

The Doctor Still Counts

“Today’s exams are definitely more technology-driven,” notes Dr. Awdeh. “A patient coming in for an exam may receive a battery of tests and imaging before seeing the ophthalmologist, so we already have a good idea of what’s going on with the patient by the time we see him. In the future we may not only be able to look at the tests done during that visit and previous visits, but also have information from home monitoring of relevant metrics. We’ll have an extensive dataset to analyze that should help give us a solid diagnosis and help us create a plan for moving forward. Whether that will make our job easier is another question, because we’ll have even more data points and pieces of information to assimilate in a short amount of time. It might make our jobs harder. It will definitely make the analytical and problem-solving abilities of the doctor even more critical during the examination.

“However, the history and physical examination will continue to be an important part of medicine,” he adds. “I don’t see that being replaced by technology, at least in the next 10 years. I think technology will simply supplement our role as physicians, and the role of patients in the examination.”

“In the future I think patients will see doctors employ clinical decision support tools from an artificial intelligence source such as IBM Watson,” says Dr. Chang. “Super-computer neural networks and deep learning are being applied to digitized health information. Nevertheless, people don’t want a robot taking care of them; they want a human with empathy. In my mind, that’s probably the most important thing the physician provides, along with good outcomes. Everyone wants the highest-quality care delivered by a person who understands his perspective and cares about him.”

“Patients still want to talk to the doctor,” agrees Dr. Lord. “They still want to meet face to face and have the doctor be upfront and transparent about what their situation is. We’ve gotten better at using tools like instructional videos, helping patients understand what their condition is and what their surgical needs are, and we have better instruments, but I’m pretty sure the doctor-patient interaction hasn’t changed much.

“On the other hand, we’re being pushed to be more accessible and digital in many areas,” he says. “We’re managing electronic records; the vast majority of our prescriptions have to be sent electronically. Our EHR systems are being designed so that we can digitally communicate, doctor to doctor. We’re expected to communicate with our patients electronically. Of course, there are good and bad sides to this. It’s a monster project to get all of this up and running. But in the right practice, all the digital communication does reduce the number of phone calls and helps with medico-legal issues. And either way, for good or bad, it’s the way things are headed.”

Dr. Lord believes the trend toward digital, mobile interaction is likely to continue for some time to come. “The baby-boomer generation is now one of our prime demographics, and I don’t know many baby boomers that haven’t adopted this kind of technology,” he says. “My parents are in that demographic, and they’re pretty tech-savvy—and they’re from a small town. I think that if your practice hasn’t adjusted to this, it needs to. This is not going away.” REVIEW

Dr. Chang has a financial interest in the EyeGo intellectual property. Dr. Awdeh has a financial interest in the CheckedUp platform. Dr. Lord is a partner in Cloud Nine Development, developer of the Eye Handbook app; however, Dr. Lord notes that the app is free online.