The Systems

For angiography of the typical diabetic retinopathy or vein occlusion patient, there are three main systems that clinicians routinely use.

• Heidelberg wide-field viewing module. This is an add-on, non-contact lens for the Heidelberg Retinal Angiograph-2 or the Spectralis OCT that allows the user to select an angle of view of 51 degrees, 68 degrees or 102 degrees when doing fluorescein angiography. Users say that, with some “steering” of the patient to get him to look in certain directions as the test proceeds, the system can add to the field of view. “Its wide-field setting is 102 degrees,” says Jarrod Wehmeier, ophthalmic photographer at the Retina Institute in St. Louis. “However, I think you can add 20 to 30 degrees in each direction by having the patient look around in different directions.”

The Retina Institute’s Gaurav Shah, MD, who consults for Heidelberg, says one advantage to him was that the wide-field viewing was just an add-on for an instrument he already owned, rather than a new capital equipment purchase in the six-figure realm. “It didn’t make sense to spend the extra money vs. just getting an add-on lens that costs about $20,000,” he says.

|

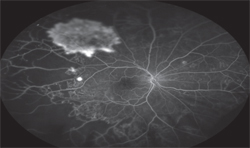

• Optos 200Tx. The non-contact Optomap 200Tx allows clinicians to acquire angiographic data on the retina with a 200-degree field of view. As with the Heidelberg wide-angle viewing system, the user can steer the Optomap patient, yielding an even larger area for examination. “Sometimes people forget you can steer the patient with the Optos,” says Szilárd Kiss, MD, director of clinical research and associate professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. “If the photographer sees something he wants to focus on, he can still steer the patient’s gaze.”

When a user views Optomap images, Dr. Kiss says there are some aspects he’ll need to get used to. “There are some trade-offs that are inherent in all wide-field imaging systems as well as the ellipsoid mirror used by Optos,” he says. “When one views a spherical surface on a flat monitor, the periphery will not have the same representation as the posterior pole. This is akin to the same issues faced by mapmakers in which their maps make Greenland appear several times the size of the U.S., when in fact, it is about one third the size.” Dr. Kiss points out that there are software fixes that are now being worked on to correct for this peripheral non-linearity.

“Some have talked about the Optos losing some resolution in the posterior pole,” Dr. Kiss adds. “But this is unfounded. I always challenge my colleagues to show me something on conventional imaging in the posterior pole that you couldn’t see on wide-field imaging. You can see everything in the posterior pole that you need to see with the Optos ultra wide-field image.”

• Staurenghi lens. This is a contact-lens based viewing system that attaches to a scanning laser ophthalmoscope such as the HRA2. It can provide a 150-degree viewing field, with the drawback that it needs to make direct contact with the patient’s cornea in order to make this view possible. Though it yields good images, Dr. Shah says a non-contact system often suits the patient flow of his practice better. “We find it difficult to use a contact system with the volume of patients we see,” he explains. “Even though it may give better images, sometimes you have to make sure you can do a test efficiently.”

It’s worth noting that though the contact RetCam system does wide-field imaging, it’s almost exclusively used for diagnosing and managing retinopathy of prematurity.

Putting the Systems to Use

Users of wide-field systems say that, when you use them properly, they may provide information that you might have otherwise missed. Here are the potential benefits of wide-field imaging, and tips on how to achieve them.

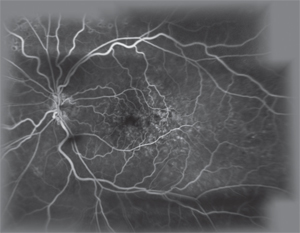

• Extra information. Before wide-field imaging systems, clinicians relied on the seven standard fields, which involved the use of traditional lenses aimed at different areas of the retina to form a composite image that provided approximately a 75-degree field of view. “The seven standard fields used to be the gold standard in viewing conditions such as diabetes,” remarks Dr. Kiss, who adds that retina specialists have always been interested in seeing more of the retina, but were just limited. “Now, examining the periphery as Lloyd Paul Aiello, MD, and our group have done in some of our studies has made us realize that the classification of a patient’s disease can actually change based on peripheral features,” Dr. Kiss says. “Dr. Aiello found that patients’ disease severity may be different depending on where the lesions are located,1 and he found that a third of the lesions were outside the standard viewing fields. If you’ve got more lesions in the periphery, a patient may progress faster. Knowing details such as these will influence how often you follow-up with a patient and perhaps even when he’s going to need treatment based on the condition of his peripheral retina.”

|

The nature of angiography itself may make wide-field imaging’s information more useful than just creating a montage of single images from a traditional lens. “If you’re using a traditional-sized lens to shoot five or six photos around the globe to get the peripheral retina, you may be off by one or two minutes compared to the dye circulating in the eye,” notes Dr. Kiss. “By the time the patient resets and then you reset, you may not get the pathology. Also, with a montage it helps to know what you’re looking for. If you’ve got a patient with a pathology in the superotemporal quadrant of the far periphery, it’s easy to tell the photographer to focus on that. But if you have a patient in whom you’re not sure where the pathology is, the wide-field imaging will get it all.”

Dr. Kiss says there’s preliminary data from single-site studies that laser treatment based on peripheral retinal data might reduce the treatment burden in the future. “First, a caveat: This all remains to be proven in larger, multicenter trials, but there’s some indication that, in patients who have an incomplete response to anti-VEGF therapy—as well as the so-called ‘VEGF-addicts’—you could perhaps laser the peripheral ischemia and reduce the amount of anti-VEGF treatment you need.

“In vein occlusion,” Dr. Kiss continues, “if you look at the posterior pole, you’ll see a small vein occlusion. “But when you look in the periphery with ultra wide-field imaging, you get a sense of the extent of the disease and the disease burden. That might be why a patient needs a lot of anti-VEGF injections or multiple Ozurdex treatments. So, instead of lasering the macula, one could imagine an approach where you laser the periphery and maybe decrease the ischemic drive that way. The same thing might also be true in diabetes. We and others have published that the areas of non-perfusion in the periphery are correlated with the presence or absence of diabetic macular edema.2 Though that doesn’t imply causality, once again one cannot only imagine using this to quantify the disease burden but perhaps also treating those peripheral areas to help preserve the posterior pole and maintain a patient’s vision rather than lasering the posterior pole and possibly compromising vision.”

• Tips and techniques. Mr. Wehmeier says that, when working with the Heidelberg’s wide-angle viewing system, it can help to make some adjustments before the angiography study begins. “When you bring the patient into the chinrest, since the size of the lens is quite large you have to have the patient turn his head to a 45-degree angle,” he explains. “This isn’t a tilt of the head, just a turn. This is so the lens doesn’t hit his nose and he can look straight ahead. It gives you a nice viewing area. Also, if possible, have another person hold the lids open to make the imaging easier for you and avoid lash artifacts. I’ve been able to do it usually with a Q-Tip and have gotten great images but, if you really want to document something in the periphery, it can be helpful to have someone else on-hand. This is especially true for the first couple of times you’re doing it just to get used to the machine’s operation.” Mr. Wehmeier says he injects the fluorescein as quickly as possible, and uses the entire 5-cc injection. “I usually try to use 5 cc in five seconds,” he explains. “You’re going to need as much dye as possible in as short a time as possible in order to get a high-contrast image. If you only inject 3 cc, you’ll notice there’s not enough dye to fill the images and you’ll lose quality.”

In addition to using the ART feature described earlier to average the Heidelberg’s images, Mr. Wehmeier also says adjusting the device’s gain, or the overall brightness of the image, can help. “I try to adjust the gain so it’s up as high as possible first,” he says. “This will make for a grainy image at first but, once the dye hits the eye—when you start to see choroidal flush—I turn the gain all the way down and let the dye fill in and do its work.”

Dr. Kiss says that, with the Optomap, there’s a learning curve in dealing with the patient’s lids and lashes. “The patient is pressed up against the device, so you have to make sure the lids are out of the way,” he says. “You have to make sure he’s in the best position to get an optimal image in the superior and inferior quadrants. Some colleagues use a Q-Tip to get the lids out of the way, but we’ve found the photographer’s finger works just as well. Occasionally, the patient can hold up his upper lid to get rid of that lash artifact.”

Dr. Kiss says getting peripheral retinal details is a relatively recent development but not a new concept. “The idea that the peripheral retina is important isn’t something new,” Dr. Kiss says. “Looking back at the original discussions of diabetic retinopathy by the giants in retina, they acknowledged the importance of the periphery, but couldn’t image it efficiently.

Now we can.” REVIEW

1. Silva PS1, Cavallerano JD, Sun JK, Soliman AZ, Aiello LM, Aiello LP. Peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultrawide field imaging: Distribution and potential impact on diabetic retinopathy severity. Ophthalmology 2013;120:12:2587-95.

2. Wessel MM1, Nair N, Aaker GD, Ehrlich JR, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Peripheral retinal ischaemia, as evaluated by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography, is associated with diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:5.